Two decades after North Vietnamese troops forced Saigon to surrender and unified North and South under communist rule, the United States and Vietnam gingerly took first steps toward reconciliation. In early 1995, before full diplomatic relations were established, the U.S. State Department set up a liaison office in Hanoi to search for joint projects to foster dialog that might be the foundation for broader cooperation.

The two former enemies settled on an international drug control program as a pathway toward normalizing relations. In essence, they decided to join forces in the war on drugs. Like the U.S., Vietnam had a serious problem with illegal drugs—a plague in both their houses.

U.S. officials designated Bob Gelbard, the State Department’s top executive for international drug and law enforcement matters, and Steve Greene, deputy administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration, to lead the effort. In early June 1995 the two arrived in Bangkok to take a whirlwind tour of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia and then head to Hanoi where the first steps toward normalizing relations would take place.

“Normalization of relations” enables countries to establish full diplomatic relations, set up embassies, form business ties and make arrangements for travel between them.

I had just taken up my position in Bangkok as narcotics attaché at the U.S. Embassy. I was detailed to accompany Gelbard and Greene on their tour. Vietnam was part of my area of responsibility, but the DEA’s interests in Thailand, Laos and Burma, the “Golden Triangle,” source of much of the world’s heroin, and in Bangkok specifically, the drug’s gateway to international markets, were much more compelling. I had served in Vietnam as an Army officer from June 1968 to June 1969. Returning to Vietnam had been the furthest thing from my mind.

I knew Gelbard from his time as the ambassador to Bolivia. I had been responsible for the DEA’s jungle operations in Bolivia and Peru. My job was to deny Colombian drug cartels the coca paste they needed to produce their cocaine. Gelbard, a brilliant guy, was not your typical State Department bureaucrat. He could be as direct with his host nation counterparts as an Army drill sergeant with a raw recruit. That’s what I liked about him.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

I knew Greene from my first DEA tour in Thailand. As Saigon was about to fall to communist forces in April 1975, Greene, then the narcotics attaché in South Vietnam, was evacuated to Bangkok. I shared my office space with him while he awaited his new assignment. Over the next two decades, Greene moved smartly up DEA’s chain of command and in 1995 occupied its second-highest position.

I was excited about being part of the effort to mend fences with Vietnam, but also apprehensive. If the Vietnamese government accepted our proposal, it would be my responsibility to make it work, which would mean making nice with my former enemy. The Vietnamese would know that I had been an Army intelligence officer and that my service included six months as an adviser to the intelligence staff of the 18th Infantry Division, Army of the Republic of Vietnam. It concerned me that they might hold my prior service against me—making my job much more difficult, if not impossible.

We landed at Noi Bai International Airport on June 14, 1995, and the police escorted our motorcade into Hanoi. I was surprised to find such a beautiful town. There were dozens of lakes, tree-lined streets with shop-houses and a few old French villas scattered about. Motor scooters buzzed about the streets like swarms of bees. The city is low-lying and protected from surrounding waters by numerous dikes. During the war I wondered why we hadn’t blown up the dikes to flood the city and put the North Vietnamese out of business. After entering Hanoi, I was glad we had not taken such action.

We checked into the historic Metropole Hotel, its wooden-floored rooms, shuttered windows and ornate balconies a throwback to French colonial times. The hotel sits on Sword Lake, named for the magic sword that according to legend was loaned by the resident Turtle God to an ancient Vietnamese emperor who used it to vanquish Chinese invaders.

Our Vietnamese hosts wined and dined us. They took us on a city tour intended to leave no doubt in our minds that their country had survived quite well despite our superior might.

They showed us Ho Chi Minh’s tomb, the carcass of a B-52 bomber shot down over Hanoi and the statue of a shackled John McCain erected on a bank of Truc Bach Lake where his Navy jet had crashed after being shot down in 1967. The future U.S. senator spent 5½ years as a prisoner of war.

During some free time, I slipped away with Greene, a Marine Vietnam veteran, to pay our respects at the “Hanoi Hilton,” the snide nickname tortured American captives gave to the prison that its French builders named Maison Centrale and the North Vietnamese called Hoa Lo prison. During one of my subsequent visits to Hanoi I happened by the compound and witnessed its remaining walls being knocked down to make way for Hanoi Towers, a shopping mall and business office complex. But the gatehouse remained and was later turned into a museum. Hoa Lo had been a prison for many Vietnamese dissidents during France’s almost 100-year rule.

Our formal meeting with the foreign minister the next day, June 15, did not go according to the State Department’s script. After some diplomatic foreplay, Gelbard tossed a proposition onto the table: movement toward recognition in exchange for cooperation on international drug control. Before the minister could even open his mouth to reply, President Bill Clinton knocked Gelbard’s diplomatic legs out from under him. That very day, the White House signaled to the Vietnamese government the president’s intention to normalize relations with Vietnam contingent only upon its continued, longstanding commitment to account for Americans still missing in action to the fullest extent possible. No mention was made of cooperation on the drug issue. The normalization policy was formalized in a White House ceremony on July 11, 1995.

Gelbard was upset that his proposal had been overshadowed by Clinton’s announcement and wasn’t the historic milestone he had hoped to add to his record of diplomatic achievements. However, he did successfully open the door to cooperation on drugs.

The Vietnamese saw no reason not to work with us. Their police would get training and equipment to help curb their own domestic drug abuse problem. From our perspective, a DEA presence in Vietnam would help us gather intelligence on drug trafficking organizations that might be linked to drug gangs in the United States, and perhaps Vietnamese authorities would work with us to intercept Thai trawlers smuggling heroin through their waters to Hong Kong.

Over the next three years I continued the dialogue, returning 10 times to Hanoi for various meetings at the U.S. Embassy, which officially opened in August 1995. During each visit I’d schmooze with the national chief of police and local law enforcement authorities to strengthen the relationship. I tagged Special Agent Tom Harrigan, who later became the DEA’s chief of operations, to commute between Bangkok and Hanoi to start building the working relationships needed for any enforcement success. A permanent DEA office was established at the American Embassy in Hanoi the year after my tour of duty ended to continue that work and is operating to this day.

I had another asset in this effort, Special Agent Ly Ky Hoang, a Vietnamese-American who accompanied me on each of my visits. Ly had been chief of the Saigon Police Department’s narcotics squad until 1975 and worked closely with the DEA. When Saigon began to crumble, Greene was instrumental in getting Ly and his immediate family evacuated to America. Hired by the DEA as an intelligence analyst, Ly worked his way up to become a criminal investigator.

At first I was concerned that Ly’s former status as a South Vietnamese official might complicate matters in talks with the postwar communist government, but his thorough knowledge of Vietnam’s history and culture, his insights into the personalities of government officials and his fluency in the language were invaluable in accomplishing our goals.

Clinton named Douglas B. “Pete” Peterson America’s first ambassador to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Peterson, a retired Air Force colonel, was a prisoner of war for six years.

Like fellow POW John McCain, he was a driving force in Washington for normalizing relations. Peterson served three terms as a Florida member in the U.S. House of Representatives but had decided in 1995 not to run for re-election in November 1996. Clinton nominated him in May 1996 for the ambassadorship. Peterson arrived in Hanoi in May 1997. While serving as ambassador, he married a Vietnamese-born Australian, Vi-Le, in 1998, literally strengthening the bonds between the U.S. and Vietnam.

My duties in Vietnam also took me to Ho Chi Minh City, which many locals still called Saigon, to meet with the city’s chief of police. That gave me the opportunity to visit some of my old haunts for the first time in almost 30 years. The city had grown dramatically in the ensuing decades. Its streets were jammed with cars, buses and trucks jockeying for space—the mirror opposite of low-rise, slow-paced Hanoi. The pragmatic socialist government knew better than to mess with the capitalist industry of Ho Chi Minh City, the engine of the nation’s booming economy.

Yet Ho Chi Minh City wasn’t without disappointments. The War Remnants Museum boasted captured American tanks and aircraft and spewed accusations of American war crimes, painting us in the worst possible light. Young men roamed the streets, apparently having been sired by American GIs and abandoned by their Vietnamese families. The shell of the old U.S. Embassy in Saigon was left standing as a monument to North Vietnam’s ousting of America. Peterson made its razing a precondition for opening an American consulate there.

Many of the venues I remembered were changed or gone altogether. A wooden hammer and sickle hung behind the front desk at the Rex Hotel, a reminder of the era that had followed ours. The hotel’s open-air, rooftop O Club—with $2 steaks and nightly entertainment—had been a favorite of mine during the first six months of my one-year tour of duty. Now the club’s white metal tables and chairs lay on the roof in rusting heaps.

Ly and I couldn’t find the Ponderosa, the French villa that headquartered the 525th Military Intelligence Group, where I stayed while working with Operation Hurricane, which was implemented to prepare Saigon’s defenses for another Tet Offensive, following the one in early 1968. Once that likelihood had faded, the operation was disbanded, and I was reassigned as assistant logistics officer of the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion in a compound at the foot of Saigon’s Binh Loi Bridge. We couldn’t find that compound either.

We drove a rental car east through the boonies to Xuan Loc, about 35 miles from Saigon. It was the former home of the ARVN 18th Infantry Division, where I spent my last six months with Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Advisory Team 87.

I told Ly the compound where I stayed wouldn’t be hard to find because it sat just across the road from the airstrip where we launched search-and-destroy missions in Huey helicopters equipped with guns and searchlights, called fireflies. I figured by now it would be the town’s airport. When we reached Xuan Loc we were told there was no airport.

After driving in circles, we stopped an elderly woman with red, betel-nut stained teeth carrying two buckets of coal on a long pole cradled over her shoulders. She remembered the old airstrip and pointed across a field toward a stand of trees.

We parked and walked through the tree line into a small village where Ly asked the first fellow we found if he could direct us to the airstrip. “You’re standing on it,” he told Ly, pointing to our feet. The locals had built their small village around the abandoned, now crumbled macadam pavement.

The man told us he had been in the 18th Infantry Division and invited us into his grass hut for tea. His old army helmet hung on a stake at the front entrance, its only decoration. We sat on the dirt floor as he served us hot tea in tiny chipped cups and then proudly took us on a tour of his mushroom farm.

Before we left Xuan Loc I bought the entire jar of hard candy at the tiny wooden kiosk that served as the village’s general store and cafe and handed it out to kids who had gathered to gawk. I also left a handful of dong, the Vietnamese currency, with the store’s owner, which Ly told me was enough to buy rice wine for our host, my old comrade in arms and his buddies for a month.

Once I found the old airstrip, I was able to locate the MACV compound. It was totally overgrown when we drove by. A guard was posted at the front gate with an AK-47 assault rifle slung over his shoulder. A sign on the gate read, “NO PHOTOGRAPHS.” The building must have been a supply depot, perhaps for weapons or ammunition. Ly thought it best not to stop.

Back in Ho Chi Minh City we drove to Ly’s childhood home. His parents, who had immigrated to the United States some years after he did, were allowed to take only one suitcase apiece, leaving virtually everything they owned behind. The woman who now occupied the home welcomed us in to look around. The furniture owned by Ly’s parents was still there, in exactly the same place where they had left it. Ly spotted the tiny lacquered table where he ate as a child. With tears welling in his eyes, he asked me to take some pictures for his parents. I realized then that even those who escaped the communist takeover had paid a heavy price.

With rare exceptions, the Vietnamese people themselves seemed to hold little animosity toward Americans. The only instance I personally observed occurred in late 1996 when I spoke at the graduation ceremony for the DEA’s first international training course in Hanoi. I had just started my remarks when there was a scuffle in the back of the auditorium and one of the students was escorted from the room. Afterward, the director-general of police apologized profusely, explaining that the officer, whose brother was a North Vietnamese soldier killed in the war, had become emotionally distraught. I can only imagine that after a week with DEA instructors he was having second thoughts about closer ties with the Americans.

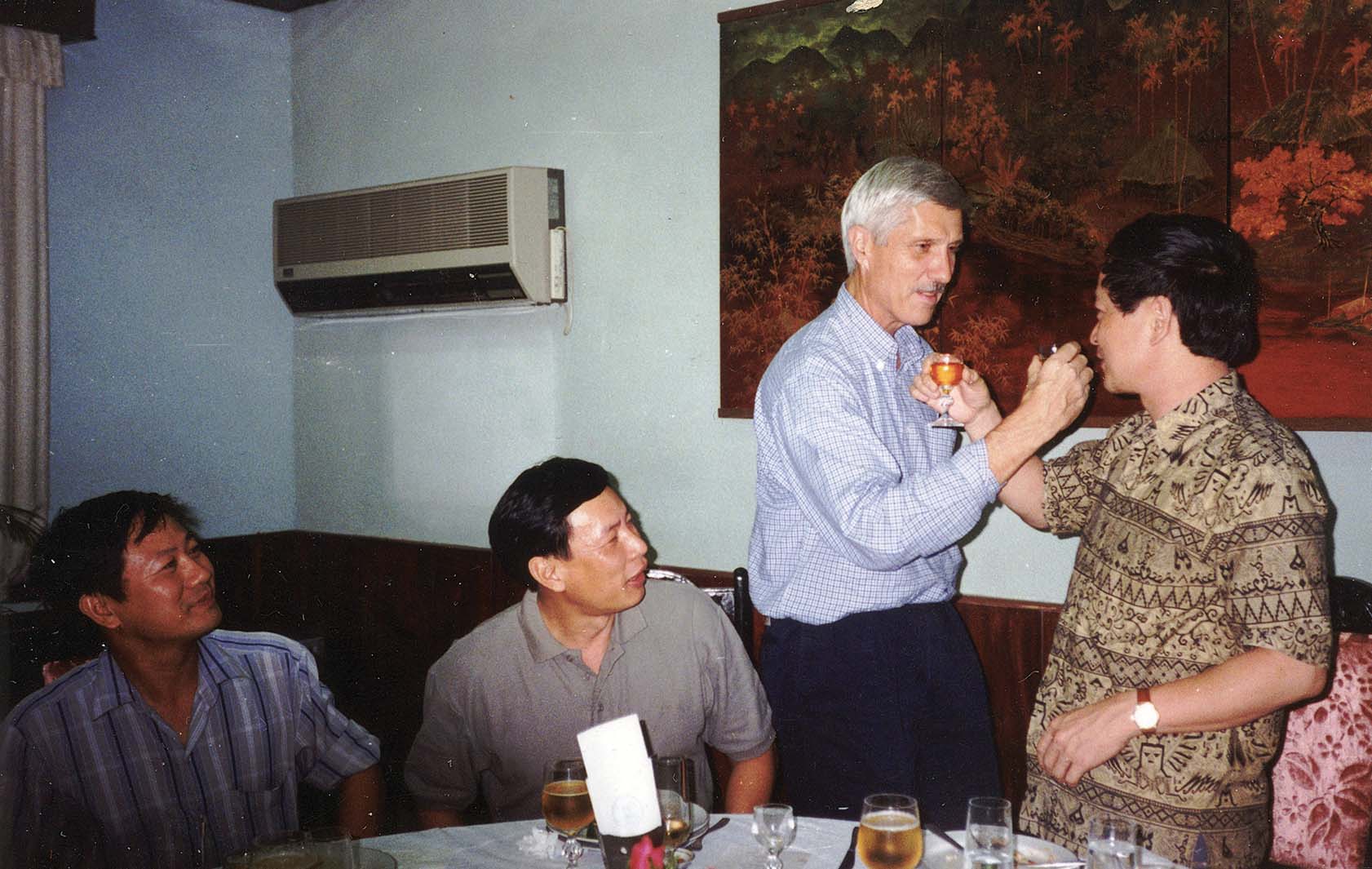

I had taken my wife with me on that trip. In the evening we attended a banquet hosted by the interior minister to thank the training team for its work. In a government hall along Sword Lake they set out an array of local delicacies fit for an emperor. There were rounds of toasts to each other’s organizations and to the improving relationship between our two nations. After raising our glasses, the hosts had us interlock arms with theirs and say in English, “Bottoms up,” before tossing down each shot of cognac—the national drink, another legacy of the French. The toasts went on for some time. I don’t remember getting back to the hotel.

My three years working to improve relations with the Vietnamese government forced me to put aside any ill will that I may have held for my former enemies and gave me a different perspective on the war, one that crystalized while sipping a Vietnamese-made “33 Beer” at the American-owned R&R Hanoi Tavern. A Vietnamese guy sitting next to me struck up a conversation. He spoke English pretty well, and I’m certain he just wanted to practice a bit. At one point I asked him what he thought of the war. “Which one?” he replied.

His response got me thinking. For most Vietnamese people living today the war with the Americans is just another chapter in their history books after wars with China, France and Japan. They paid a dear price during the protracted war with us. Some estimates put total human losses at more than 1 million during that era. Yet, for the most part, they had moved on.

The United States paid a high price as well.

More than 58,000 Americans lost their lives taking a stand against communist aggression in South Vietnam during the Cold War. It took 20 years before we were finally able to move on.

During the 20-plus years since the beginning of that joint effort in the battle over illegal drugs, the relationship between our two nations has blossomed, despite Vietnam’s poor human rights record, and we are allied in another concern: China’s ambitions in Southeast Asia. There has never been any love lost between Vietnam and China, even though China supported the communist Hanoi regime during the war. This time the Hanoi government could be on our side. Maybe the Vietnamese could get that Turtle God to loan us his magic sword. V

Charles Lutz was commissioned an Army intelligence officer through the ROTC program at Pennsylvania State University in December 1967. He deployed to Vietnam in June 1968 and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for meritorious service with MACV Advisory Team 87. Lutz concluded his active duty at the Continental Intelligence Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, before beginning a 32-year career as a special agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration. He lives in Salem, South Carolina.