Union veterans had no doubt about Gettysburg’s significance as a turning point in the conflict

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]fter two days of fierce combat and rampant carnage, the Battle of Gettysburg climaxed on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, when 12,000 Confederate troops failed to break the center of the Army of the Potomac’s line on Cemetery Ridge. As the defeated Confederates retreated back to Seminary Ridge, exultant Federal troops cheered, and some taunted their Army of Northern Virginia foes with revengeful chants of “Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!” Meanwhile, General Robert E. Lee lamented as his defeated men streamed by, “All this has been my fault—it is I that have lost this fight.”

Such riveting drama has cemented Gettysburg’s place in American history and popular memory. More than one million visitors travel to Gettysburg National Military Park annually. The Battle of Gettysburg’s influence in Civil War scholarship is indisputable and its dominance in popular debates is incomparable. Now, more than 150 years after the battle, the question of whether Gettysburg was the war’s turning point remains a popular and often contentious topic.

Recently, historians have posited that Antietam, Vicksburg, Sherman’s March to the Sea, or Grant’s arrival in the Eastern Theater had more significance than Gettysburg in altering the trajectory of the war. In a 2012 lecture at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Gary Gallagher, among the nation’s leading Civil War historians, offered that the spring 1862 Seven Days Campaign was a more significant turning point than Gettysburg.

But, it’s instructive to go back and examine how soldiers who fought in the war’s Eastern Theater viewed the battle. Indeed, veterans of the Army of the Potomac believed that the engagement that shaped the course of the conflict more than any other occurred in July 1863 in Pennsylvania. For men who had survived the huge battle, those transcendent three days were the war’s defining moment, the nexus of the Civil War, and also one of the world’s watershed events.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n proclaiming Gettysburg’s importance, men who had fought in the Union Army characterized the battle with decisive consequences, militarily and politically. They recounted a Federal victory over a proud, mighty Confederate Army, one that never again reached comparable strength or posed such a threat as it had in the summer of 1863. By turning back the Southern tide, Union soldiers argued they had preserved the nation’s most guarded principles, freedom, democracy, and liberty. Having vanquished the enemy from Northern soil, Gettysburg became the “great crowning struggle of the war,” as a Michigan veteran described it in 1889.

That sense of importance, however, was not just a postwar construct. As soon as the Battle of Gettysburg came to a close, the Union rank and file began to appreciate the significance of their victory. For an army that had never experienced a resounding victory over its Confederate foe, Gettysburg provided an invaluable boost to confidence and morale, particularly critical for troops that had suffered through a string of unremarkable commanders.

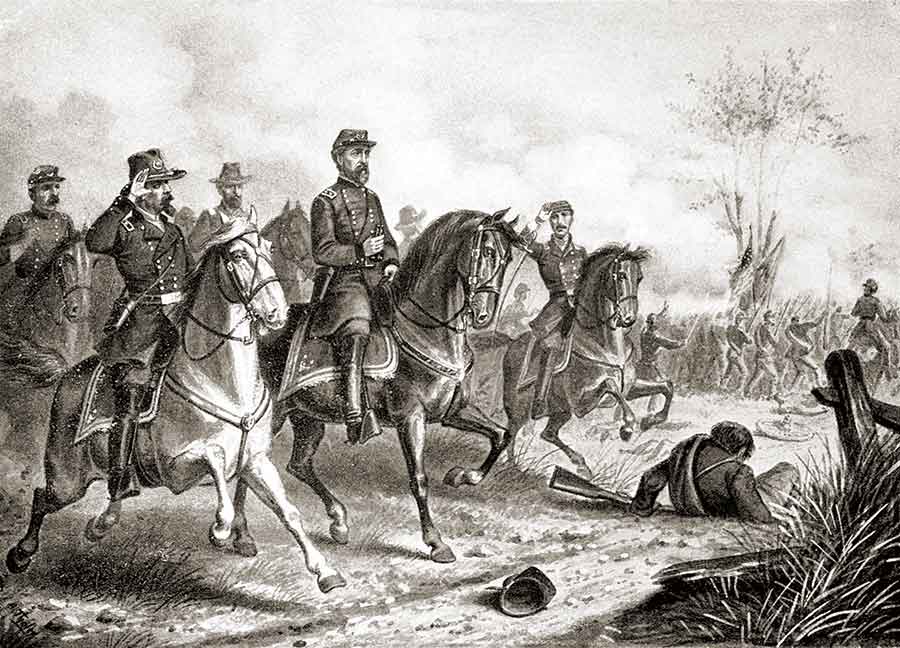

Major General George Gordon Meade, previously commanding the army’s 5th Corps, had assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863, representing the army’s third change in command that year. Three days later, Meade led the army in its most significant battle to date and proved capable of doing what no other Union commander had yet accomplished: defeating Lee. Although an unfamiliar face to many in his command, several hours after the repulse of Pickett’s Charge, Meade rode along the Union lines, greeted by enthusiastic cheers from his men. The uproar reached the Confederate positions one mile to the west. Arthur Fremantle, a British officer attached to the Army of Northern Virginia as a foreign observer, heard the “long and continuous Yankee cheer.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The great battle of the war has been fought – Elisha Hunt Rhodes, 2nd Rhode Island Infantry[/quote]

On July 4, Meade offered his men a congratulatory order that placed their deeds and sacrifices in the war’s grand narrative. “The privations and fatigue the army has endured,” the commanding general declared, “and the heroic courage and gallantry it displayed, will be matters of history to be ever remembered.” Meade’s words would prove prophetic.

As the chaos of battle subsided, Union soldiers began to write about the fight they had just survived and to reflect on the importance of the Federal victory in Pennsylvania. Diary entries and letters to loved ones readily defined Gettysburg as a decisive battle. “The great battle of the war has been fought,” wrote Elisha Hunt Rhodes, 2nd Rhode Island Infantry, “and thanks be to God the Army of the Potomac has been victorious at last.”

Others shared Rhodes’ sentiment as they sought to find meaning in the necessary bloodshed at Gettysburg. Writing of the army’s “glorious” victory, Corporal James Porter Stewart of the 1st Pennsylvania Artillery declared the battle a “grand and decisive victory.” On July 4, Horatio Dana Chapman, a soldier in the 20th Connecticut, wrote: “The rebels during the night have retreated for sure and we have gained a glorious victory and we feel elated and joyous and start in pursuit.” Taking a moment to consider the historic significance of the date, he added, “This day reminds us of our Independence and what it costs to achieve it and what it is now costing to maintain it.”

Perhaps such characterizations are to be expected from the men in Meade’s army, boasting of their well-earned victory. Similar sentiment, however, pervaded the Northern press. Within days after the battle, correspondents and editors crafted Gettysburg into the war’s defining moment. Northern newspapers extolled the fighting qualities of the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, citing examples of brave deeds and acts of heroism.

Most famously, a mere three days after the battle and before the campaign ended along the Potomac River, Pennsylvania’s leading newspaper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, headlined “Waterloo Eclipsed!” Such declarations were not limited to Pennsylvania newspapers, and other comparisons to battles of the French Revolution soon followed. On July 10, the New York Herald proclaimed, “As Valmy was the decisive battle of the French Revolution, so is Gettysburg in the war of the American rebellion.” The Detroit Free Press predicted that Union victory at Gettysburg had “changed the entire aspect of our domestic question, and has opened the path to honorable peace.”

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]y the summer of 1865, the Federal armies and navies had secured the preservation of the Union. In the decades to come, Blue and Gray veterans created and shaped a narrative of the Civil War, one defined by their personal experiences, perceptions, and memories. In doing so, they attached layers of meaning to the war’s battles, elevating some engagements to heightened significance.

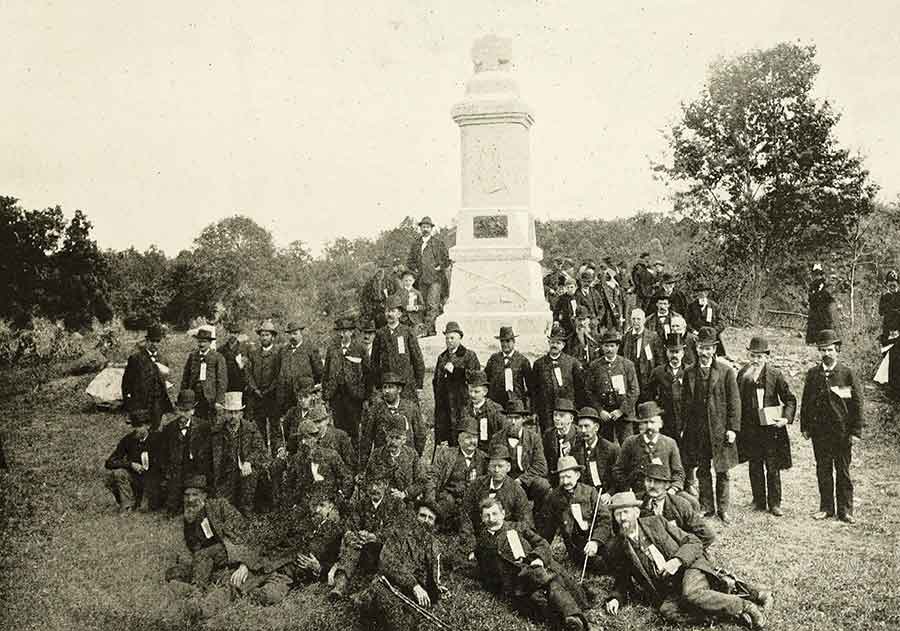

Invariably much of the postwar commemoration involved men from the war’s principal armies—the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia—and they put on scores of commemorative activities. No outlets proved as powerful for sharing and debating the war’s memories than the fields of battle. In the final decade of the 19th century, the federal government authorized the establishment of the first national military parks, ushering in what historian Timothy B. Smith has called a “golden age of battlefield preservation.” The four Civil War parks created during this time, Chickamauga and Chattanooga in 1890; Shiloh in 1894; Gettysburg in 1895; and Vicksburg in 1899; had long been cited for their significance and marked by monuments and memorials, but they also became sites for national reconciliation.

(Library of Congress)

At commemorative activities, orators at Gettysburg crafted the battle as a defining moment of the Union cause and of the Civil War. This rhetoric proved unique in postwar commemorative traditions. In dedication speeches at Shiloh, for instance, orators recounted the fighting of April 1862 and offered the expected postwar commentary on reconciliation, but backed away from ranking the battle in the same hierarchy as Gettysburg. Speeches at the war’s other battlefields often looked inward, focusing on that particular battle and landscape, while Gettysburg speakers not only eloquently recounted the fight, but did so while looking outward, transforming the battle into the lone engagement that decided the fate of the Union.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]ging veterans of the Army of the Potomac returned to Gettysburg to pay tribute to those who “gave the last full measure of devotion” on that field. The three-day struggle also served as a platform to champion the Union cause and its preservation. Speakers reinforced the belief that Gettysburg was “The High Water Mark” of the rebellion, and even championed its place among the world’s defining moments.

In June 1889, Austin Blair, Michigan’s wartime governor, delivered a speech that typified the rhetoric of many postwar tributes. Applauding the North’s citizen-soldiers as men who volunteered for service “with an intelligent sense of patriotic duty,” Blair credited the Union soldier for standing true to the Union flag for “those three murderous days the country owed its deliverance from the untold evils that menaced it.”

Of the momentous consequences of Union victory at Gettysburg, Blair offered, “the existence of the republic had hung suspended on the issue for three terrible days; that the dead and wounded heroes there had saved us and the country forever.”

During an 1893 reunion on the battlefield, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, who commanded the 12th Corps during the battle, charged, “Upon no battle ever fought were such great results depending. It was the turning point in our Civil War.” Another veteran declared Gettysburg a “struggle for our home, as well as for our National life!” Gettysburg was, 76th New York veteran A.P. Smith declared, “the first great battle after this Government had abolished slavery and taken a high stand for the right.”

On October 4, 1888, 25 years after the battle, hundreds gathered along the first day’s battlefield for the dedication of the 80th New York Infantry monument, a regiment that had seen fierce combat on July 1. Cornelius Van Santvoord, the regimental chaplain, declared in his speech that, “The battle of Gettysburg was the turning point of the Civil War.” If listeners found the chaplain’s declaration hyperbolic, he offered a lengthy explanation to his claim. Gettysburg, Santvoord argued, stood as the “supreme effort” of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to achieve a decisive victory on Northern soil to obtain an independent Confederate nation. The shattering losses that Lee’s army suffered in the Keystone State, Santvoord maintained, turned the tide of the war for the Confederacy, making their efforts after July 1863 to be of “simple preservation.”

(Library of Congress)

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he men of the Army of the Potomac also looked outward to view their victory at Gettysburg as an important moment in the trajectory of world history. Two historical epics offered the most common comparisons: Waterloo and ancient Greece. For 19th-century Americans, the Napoleonic Wars lingered in the nation’s collective consciousness, offering the ready analogies for Civil War battles, and the Philadelphia Inquirer made such a comparison just three days after the battle.

The comparison of Gettysburg to Waterloo reemerged in postwar dialogue. Federal soldiers believed their achievements to be equal to the British and Prussian soldiers who defeated Napoleon’s forces and expelled the dictator from Europe. Like Waterloo, offered Governor Blair, Gettysburg became one of the “great battles of history in which the fate of nations has been determined, and the progress of mankind in civilization and knowledge has been promoted. On the farm fields of Adams County, the fragile American Republic was preserved.” Like the British and Prussian forces ending Napoleon’s reign, thereby changing the trajectory of European history, so too had Union soldiers participated in a battle of similar consequences.

Other speakers echoed these sentiments. At the dedication of the 76th New York monument on July 1, 1888, A.P. Smith used the occasion to cast Gettysburg’s importance in the war’s trajectory and the Union cause. “To this historic battle shall they look not only for incident and entertainment, but as the world looks at Waterloo—as the one battle which turned the tide of war and determined the struggle.” There were other comparisons the New York veteran provided, “Three battles are most famous in the world’s history—Marathon, Waterloo, and Gettysburg.” Each of these battles, Smith maintained, brought forth the “elevation of mankind and the advancement of civilization.”

In their efforts to insert Gettysburg into the world’s master narrative, Northerners also found comparisons to the battles of ancient Greece, specifically Marathon in 490 BCE and Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Both of those engagements pitted the Greeks against the Persians in a quest for sovereignty and supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea. While greatly removed from the ancient Greeks, both in space and time, the conflict between the Greeks and the Persians offered fitting analogies to the strife between North and South. Honorable Orlando Potter of New York likened Gettysburg to Thermopylae and predicted that visitors to Gettysburg would “drop tears of gratitude for the preservation of the Union here achieved.” To modern historians, such comparisons to ancient battles may have overdone the singular importance of Gettysburg. But to Union veterans, the Pennsylvania fight ensured “that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

By expanding the interpretive lens beyond Gettysburg to look for turning points during the war, scholars have produced invaluable contributions to our understanding of the war’s military operations. These interpretations, however, have minimized the voices of the soldiers, and particularly the veterans of the Army of the Potomac. For the men who fought at Gettysburg, those three hot days in July defined their Civil War experience. Their turning point was Gettysburg.

Jennifer M. Murray is an assistant professor of history at Oklahoma State University, and the author of On a Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013. A former interpretive ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park, she is currently working on a biography of George Gordon Meade.

John Bachelder’s Dream

No individual proved more responsible for blurring the lines between history and memory at Gettysburg than John Badger Bachelder. In doing so, Bachelder singularly created one of Gettysburg’s most enduring canons, “The High Water Mark of the Rebellion.”

Born in New Hampshire in 1825, Bachelder made his living as a landscape painter and photographer. He was not a Union soldier, nor did he witness the fighting at Gettysburg. Upon hearing of the battle, however, Bachelder traveled to the Pennsylvania town just days after the fighting.

He proceeded to study the terrain, interview Union and Confederate soldiers, and become the engagement’s earliest historian. Over the next three decades, Bachelder committed his life’s work to documenting, preserving, and marking the landscape of the three-day fight.

Arguably, Bachelder’s greatest influence came in his interpretation of Pickett’s Charge, the Confederate assault on July 3. Several years after the battle, while walking along Cemetery Ridge with Colonel Walter Harrison, Confederate Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s adjutant general during the battle, the Southern staff officer recounted the importance of a copse of trees along the Union line. Harrison claimed the trees had served as an aiming point for the famous Confederate charge, and Bachelder responded, “Why, Colonel, as the battle of Gettysburg was the crowning event of this campaign, this copse of trees must have been the high water mark of the rebellion.” The “High Water Mark” concept was born.

In subsequent years, Bachelder worked to memorialize the Copse of Trees and craft Pickett’s Charge and the Gettysburg Campaign as the war’s High Water Mark. He convinced Basil Biggs, the African-American farmer who owned the property that included the copse, not to cut down the trees. In 1881 Biggs sold his land to the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), the battlefield’s first preservation entity.

In 1887, the GBMA erected an iron fence around the copse. The following year, Bachelder proposed the idea of a memorial at the trees. After much deliberation and multiple designs, Bachelder’s efforts came to fruition in 1892. On June 2, thousands of people gathered for the dedication of the High Water Mark of the Rebellion monument on Cemetery Ridge. The open book tableau memorial lists both Union and Confederate units participating in the assault, and proved a popular gathering point for Union and Confederate veterans during the reunions in 1887, 1888, and 1913.

Today, the High Water Mark monument is one of the most visited sites on the Gettysburg battlefield. And while many historians have challenged Gettysburg’s place as the war’s defining battle, the High Water Mark interpretation remains entrenched in popular memory. John Bachelder achieved his objective. -J.M.