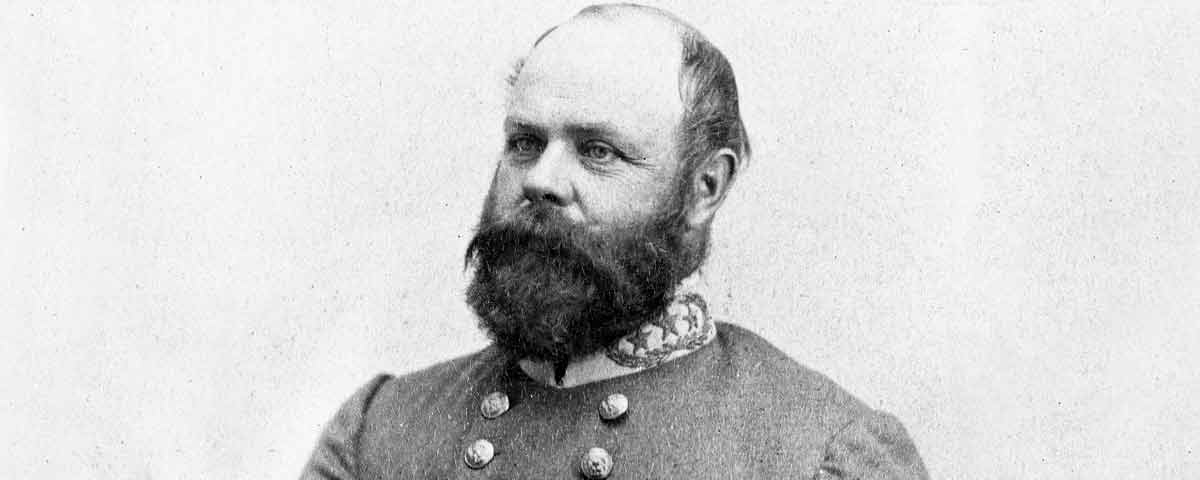

General Roswell Ripley couldn’t get along with anyone.

Not even Robert E. Lee.

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or nearly four years Roswell Sabine Ripley wore the wreath and three stars of a Confederate general officer, despite being an unmistakable Yankee by any definition. He hardly fit the image of the gallant Southern officer nobly defending the “Lost Cause,” even expressing distaste for Robert E. Lee, which put him in limited company among Confederate general officers. After the war, he earned an even more unusual credential: the only former Rebel general tapped by the Chinese to serve in the Far East.

Depending on how one counts temporary promotions, and including those from the ranks of the irregular Trans-Mississippi Theater, nearly 450 men became Confederate generals. Most were native to the South, and steeped in its culture. The story behind the name of Brig. Gen. States Rights Gist, for instance, thoroughly resonates with Confederate origins.

Four hundred of these generals were born and lived most of their lives south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Nine had been born abroad. Only 34 were natives of Northern states, all of whom had emigrated to the South by 1861. The majority of these transplanted Yankees married Southern women, including the Confederate Army’s highest-ranking general, Samuel Cooper (b. New York); Vicksburg’s luckless defender, John C. Pemberton (b. Pennsylvania); and the Confederacy’s last commissary general of prisoners, Daniel Ruggles (b. Massachusetts).

Because R.S. Ripley was born in Ohio on March 14, 1823, some references call him an Ohioan. His family, however, moved to Massachusetts when he was only four, then quickly on to Ogdensburg, N.Y. His Yankee ancestry included a grandmother with an engagingly antique name: Submit Murdock Huntington.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ripley never finished lower than 7th in any of his four years at West Point.[/quote]

Ripley performed well at the U.S. Military Academy, with strong grades and good standing in deportment. He graduated in 1843, having never finished lower than 7th in any of his four years at West Point, and never having accumulated more than 55 demerits (the demerit limit was 200). Nevertheless, in apropos foreshadowing, Ripley was reportedly very unpopular with his fellow cadets.

Every West Point student before the war rubbed shoulders with youngsters later destined for Civil War prominence. Ripley’s class included William B. Franklin, William S. Rosecrans and Ulysses Grant. Among contemporaries of other classes were future Confederate standouts Thomas J. Jackson, Richard Ewell, James Longstreet, A.P. Hill, George Pickett, Lafayette McLaws, and Dabney Maury.

In a letter to his mother while a cadet in 1842, Ripley wrote about a temperance drive in progress: “There is such a thing as running that, as well as drinking, into the ground.” Given the alcohol excesses he experienced later in life, his youthful reaction at the time is fascinating.

As was typical in that era’s U.S. Army, promotion came slowly. Ripley attained his first lieutenancy only in March 1847, under the exigencies of the Mexican War, which expanded the Army exponentially. Before the war, he had served at Fort McHenry, Md.; Fort Johnston, N.C.; Augusta Arsenal, Ga.; and as a professor of mathematics at West Point. Students subjected to his rule at the U.S. Military Academy found little to like about him.

Lieutenant Ripley performed well in Mexico, first with Zachary Taylor’s column in the north, and later on Gideon Pillow’s staff. He earned brevets for the 1847 battles of Cerro Gordo and Chapultepec. Then in 1849, he made a major splash by writing an excellent, though entirely unofficial, history of the conflict. The War With Mexico filled two thick volumes, taking up nearly 1,200 pages. Ripley took leave to produce the history, and daringly—amazingly—included criticisms of the Army’s commanding general, Winfield Scott, who appears to have simply ignored them.

Ripley’s history of the war remains important, since many of the principals would become famous. An artillery lieutenant named Jackson, fighting on the causeway approaches to Mexico City, would become legendary as Stonewall, for example, but in Ripley’s narrative appears without even any identifying initials.

From Mexico, Ripley went to fight Seminoles in Florida, to Fort McHenry again, and to Fort Monroe, Va. His last prewar posting took him to Charleston, S.C., and led directly to his Confederate service. He met a wealthy society widow, Alicia Middleton, who had inherited her deceased husband’s wealth. Now a major, Ripley married Alicia and her money in December 1852. Three months later he resigned his commission. For most of the interval that followed until the onset of the Civil War, he operated an armaments business in England. It was a venture for which he unquestionably had an inside track, as his uncle, James W. Ripley, was the U.S. Army’s chief of ordnance.

Ripley became a major of ordnance in state service as soon as South Carolina seceded in December 1860. He commanded Fort Moultrie; then Fort Sumter as a lieutenant colonel after its surrender to the Confederacy in April 1861. His diligence in fortifying Charleston Harbor set the foundation for that city’s long and sturdy resistance to invasion.

Most Civil War generals, on both sides, grumbled ceaselessly about rank. Consider, for example, Joseph E. Johnston’s incessant howling about every imaginable aspect of rank and privilege. Ripley’s grumpiness on that topic led him to the point of resignation, loyalty and patriotism aside. In a July 1861 letter to a local official, Ripley listed the opportunities he had rejected. Yet, as Confederate Treasurer C.C. Memminger wrote sagely, “Ripley himself has been the only obstacle in his own way.” This selfish posturing continued for the entire war, and Ripley threatened to resign at least five times. Some of his weary superiors surely must have come to view the threats as tantalizing promises.

Ripley’s command encompassed much of South Carolina during the summer of 1861. He behaved so fractiously, however, that by October Adjutant & Inspector General Samuel Cooper wanted to get rid of him; Jefferson Davis granted a temporary reprieve. John C. Pemberton—himself widely disliked—cashiered Ripley in 1862. By then Ripley also was starkly at odds with P.G.T. Beauregard. Given their dubious credentials, hostility from those two might reflect credibly on Ripley; but in fact the anti-Ripley sentiment was about universal. A South Carolina captain wrote bluntly that Ripley was “not competent to hold an important command.”

Lee, then still relatively unknown, arrived in the winter of 1861-62 to superintend the defense of South Carolina’s coast. He found much to admire in Ripley’s endeavors regarding engineering and ordnance.

Predictably, Ripley loathed the emerging Confederate leader. Typically, Lee accepted him cheerfully despite the scorn. Governor Francis Pickens warned Jefferson Davis about Ripley’s unbalanced rants: “I fear [his] feeling…towards General Lee may do injury to the public service. His habit is to say extreme things even before junior officers, and this is well calculated to do great injury to General Lee.” Pickens considered Lee’s endeavors in his state “perfect.”

When Ripley assumed command of a brigade in the Old Dominion, the Army of Northern Virginia had not yet moved beyond early shakedown status. Ripley’s stint in the evolving army did not last long.

Ripley’s Brigade included the 4th and 44th Georgia Infantry and the 1st and 3rd North Carolina. The Georgians soon would join the renowned Doles-Cook Brigade, and the Carolinians wound up commanded by Raleigh Colston, then George H. “Maryland” Steuart.

The men called their general “Old Rip,” but they quickly learned to loathe their commander. In June 1862, Captain Jordan of the 44th wrote to his wife about “General Ripley—who is a big fat whiskey drinking loving man.”

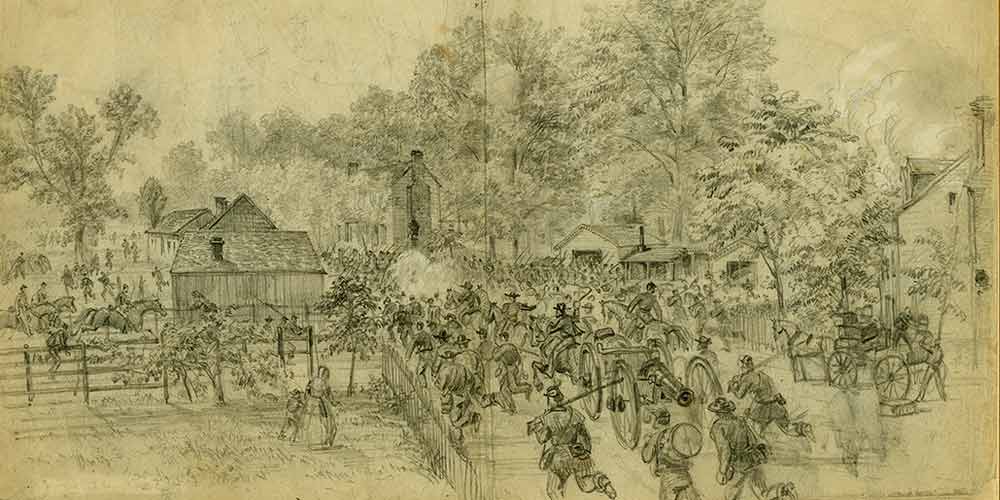

Ripley’s short career in Lee’s army—barely three months—included two high-profile battlefield episodes. Both developed into dreadful failures. He fought at Mechanicsville, Va., in June. The whole division missed Second Manassas in August 1862. His second memorable day, again bad, came at the Battle of Antietam that September.

The Mechanicsville horror spread far wider than Ripley’s aegis, but his obvious confusion contributed to the disaster. Richmond historian Clifford Dowdey turned a deft phrase in describing the general’s behavior: “If Ripley had ever understood that his movement was [intended] to turn the enemy’s flank, either he forgot it, or the effect of leading troops in combat constricted the play of his faculties.”

Captain Reese of Georgia defended Ripley after Mechanicsville. Reese blamed D.H. Hill, and called Ripley “a man of discretion…although blustering and rough in his manner.” The degree of discretion would become much mooted, then and later.

Dissatisfaction in the brigade generated widespread and public criticism. A colonel declared: “it was a common subject of conversation, among officers and men, that Ripley was not under infantry fire during the week.” Some of his staff expressed similar disgust.

Near the East Woods at Antietam, in the pasture southeast of the soon-to-be-famous Miller Cornfield, Ripley’s men fought hard, suffered much, and decided their brigadier let them down.

Colonel William Lord DeRosset of the 3rd North Carolina, a reliable witness, called Ripley an “unworthy commander,” and went beyond the usual bounds of vituperation to wish that the general had been killed: “Pity he had not then received a death wound”; “to Ripley be all the blame and shame”; “Ripley had been wounded, unfortunately for his reputation, not fatally.”

Ripley’s immediate superior, D.H. Hill, wrote with unrestrained disgust: “Ripley was a born coward—a coward or a traitor…in bad odor.” Hill’s notoriously pungent style might cause modern students to hesitate about accepting his judgments, but in fact the contemporary chorus echoed far and wide.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]James Ripley’s stubborness in not supplying Hiram Berdan’s elite Sharphooters with Sharps rifles almost caused a mutiny.[/quote]

A staffer from Charleston, whose parents liked Ripley, wrote home unequivocally just after Antietam: “Many blame Ripley entirely…and not only his generalship but his personal bravery is doubted. I am wrong in saying…is doubted, for there seems here to be but one opinion on this.”

A captain described the general at Antietam unsympathetically: “Low of stature, broad of girth, excitable by nature…Galloped down and in an excited manner gave an order to the regiment in person,” ignoring the regimental colonel.

Twelve days after the battle, from a refuge in Richmond’s Spotswood Hotel, Ripley wrote, begging to get away from the army, where it was obvious to him that Lee would never accomplish anything.The misanthropic general apparently recognized that he had irretrievably fouled his nest in Virginia.

Beauregard and Governor Pickens accepted Ripley back in South Carolina, but he immediately became immersed in yet more virulent quarrels with superiors and subordinates. In June 1863, Beauregard tried to peddle Ripley to Joe Johnston, admitting that he “is not satisfied with my system and rule…[but] could be of much use to you.” Beauregard’s attempt at what today might be called “addition by subtraction” failed.

One of Ripley’s soldiers, Alfred Mulligan, wrote with relief in August 1863, “Genl. Ripley has been superseded…here. This is a good thing. It ought to have been done long ago.”

In 1864, Ripley went to trial on formal charges of drunkenness while on duty at Fort Sumter. Witnesses testified to the fact (“from my own personal knowledge”), citing multiple instances. Fragments of the trial record survive, and contemporary accounts give some details, but the official transcript apparently burned at war’s end. Among traits witnesses ascribed to Ripley were “a looseness of morals” and “rollicking habits.”

Late in the war, Ripley also came under criticism for war profiteering in speculation and blockade running, making “lots of money.”

Surprisingly, despite the steadily querulous official record, people outside Ripley’s control often liked him, in part because he was a great raconteur. The strong-drink question, seen by those out of authority, did not matter. British observer Lt. Col. Arthur J.L. Fremantle said of Ripley: “Jovial…very fond of the good things of life.”

A Virginian who met Ripley in Charleston loved his antibureaucracy posture. The general, he admitted, was “a queer character…portly in person…pompous presence…yet [on getting to know him] easy and unassuming in manner.”

A characteristic letter from Ripley to authorities in Richmond early in 1865 demanded that he not be assigned anywhere under Beauregard. The final note in his service record, dated February 14, nevertheless ordered precisely that—report to Beauregard. In late March, during the three-day Battle of Bentonville, the disgruntled Ripley reached the army–by then under Johnston’s command. On April 26, Johnston surrendered at Durham Station, N.C., 17 days after Lee capitulated at Appomattox, Va.

In the wake of defeat, Ripley again spent much time in Europe, “in various…business affairs.” The French army, imagining an impending war with Prussia, gave Ripley a fat contract to produce rifles. The project failed utterly, by one account because the U.S. government somehow managed to confiscate the machinery on the basis of Ripley’s Confederate service.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ripley was a born coward. A traitor…in bad odor.[/quote]

Writing under a nom de plume, Ripley contributed an extensive review in 1874 to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine of the Comte de Paris’ multi-volume History of the Civil War in America. Ripley’s thesis, cogent and fluid, dismissed the Frenchman—who had served for a year in the Union Army on McClellan’s staff—as “an intruder in a stranger’s quarrel, with which he…had no concern.” “Why did he write it?” Ripley concluded that he should not have.

Three years later Ripley wrote for Blackwood’s again: the “Situation in America”—once more in smart, literate prose.

An unusual episode involved Ripley with a Chinese military commission. In January 1875, Confederate naval veteran Hunter Davidson wrote from London: “Gen. Ripley spent much of the day & dined with me yesterday. He says that he has just been appointed to the command of the northern defense of China & leaves shortly with his staff for his destination.”

Ripley had not left for the Orient by June. A Colt Arms representative in London reported that “General Ripley has been nominated chief of the Chinese defense.” The general’s appointment “was not yet certain,” Ripley had told him, but “he expects a decision [soon]…[and] would proceed to China via America.” While in the United States, Ripley planned to buy weapons from Colt and also procure a Gatling gun.

The China arrangement evidently never came about. Ripley left Europe beset with debt and returned to Charleston, but lived mostly in New York, by now entirely estranged from wife and family (daughter, step-daughter, sister, mother). Charleston street directories show the Ripleys living apart. His habitual behavior in every walk of life makes that result less than surprising.

As a historian has written in apt summary: “Wayward and mercurial to the last, he could never bring himself to any permanent attachment to an activity or a location.”

Ripley died in New York on March 19, 1887, just past his 64th birthday. His widow did not attend his funeral.

In contemplating Ripley’s historical stature, consider this: Is there any other four-year Confederate general and department commander on whom not even a biographical pamphlet exists? A slim funerary tribute by a staff officer constitutes the entire historical shelf on R.S. Ripley. On T.W. Brevard, a brigadier for the war’s last few weeks, or Zebulon York, brigadier late in the war and in a subordinate role, the historiographical gap is explicable. Ripley may deserve his low profile, but the neglect is strange.

Searching for compartments into which to wedge Ripley brings to mind the Chinese flirtation, and his unflinching surliness. Here is another: Ripley surely must be the only Confederate general buried near a sign that says something like “Beware of Alligators on the Paths.” The sign stands in Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery, near a large and lovely (and saurian-infested) lake.

Roswell S. Ripley’s life was beset by other, more serious, hazards than scaly boots-in-the-rough. He ran afoul of troubles with women, booze, and scornful colleagues in daunting numbers, and left behind a record that might be characterized as “Mixed at Best,” but “Colorful Always.”

Robert K. Krick, chief historian at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park for more than 30 years, has written extensively on the Civil War. He is the author of The Smoothbore Volley That Doomed the Confederacy.