General Daniel Ruggles turned his back on his Yankee roots to fight for the Confederacy

Daniel Ruggles was unusual. He was one of only three men born in Massachusetts to become a general in the Confederate Army. He was also fortunate. The general avoided Yankee bullets, outlasted political and military opponents in the Confederacy, and died in Fredericksburg in 1897 at the age of 87. How and why did a man from the state considered the cradle of abolition come to fight for the Southern cause?

Ruggles was born on January 31, 1810, in Barre, Mass.—still a small town in the central part of the state—to a family with a colorful military background. He was named after his grandfather, the Honorable Daniel Ruggles, who hailed from neighboring Hardwick and served as a lieutenant in the American Revolution and as a justice of the peace afterward. His great uncle was Edward Ruggles, a “Minuteman,” who fought at the Battle of Lexington in 1775 and, a few years after the Revolution, helped put down Shays’ Rebellion in western Massachusetts.

Ruggles followed in the family military tradition. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1833. A mediocre student, he finished 34th in a class of 43 cadets. His years at West Point, however, began a military career that lasted 32 years and took him all over the United States. After leaving West Point, he was stationed in Wisconsin Territory, and then saw his first action in Florida during the Seminole Wars of the late 1830s. In the Mexican War, Ruggles was twice breveted for bravery, won a promotion to captain, and fought with General Winfield Scott’s forces as they captured Mexico City. In the 1850s, Ruggles served on posts along the Mexican border, Utah, and Texas.

Given his long United States service and his deep Yankee roots, it seems mystifying that he ended up siding with the Confederacy during the Civil War. Part of the reason, however, was personal. In 1859, he was sent to Fredericksburg, Va., to recover from an illness. While there, he married Richardetta Barnes Mason Hooe, a niece of Virginia Founding Father George Mason. The couple married and had four boys, two of whom served in the Confederate Army.

When the Civil War broke out, Ruggles, despite his Massachusetts heritage, suffered none of the uncertainty that plagued some officers, such as Robert E. Lee for example, before he joined the Confederacy. A staunch believer in the cause, in 1861 Ruggles wrote that his countrymen must “make each house a citadel, and every rock and tree positions of defense” were he and his men to drive out the “insolent invader.” Ruggles had no sympathies with the abolitionists of the North.

In 1861, a week after the firing on Fort Sumter, Ruggles was made a brigadier general of militia in the newly created Provisional Army of Virginia and put in charge of the Aquia District, just north of Fredericksburg. There, the commander faced the daunting task of recruiting soldiers in the fledgling Confederacy. The war might have ended early for Ruggles. He fought at the June 27 Battle of Mathias Point in Virginia, where his forces beat back a Union Navy landing party trying to establish a shore battery on the Potomac River. During the fight, Ruggles narrowly avoided getting shot in the head by a Yankee scout.

After Lee took over the Confederate forces in Virginia, Ruggles was transferred to Fort Pickens in Florida, where he became friends with the famously prickly General Braxton Bragg. In October 1861, Ruggles was ordered to move yet again, this time to New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy. Bragg was sad to see Ruggles go, for he wrote he had “the confidence and affection of the troops….” Ruggles may have been friendly with Bragg, but he later clashed with other high ranking officers out west.

Ruggles fell ill in Louisiana in October 1861, a sign of difficulties to come. Ruggles was joining a Western army that was raw, untested, and—as events developed—prone to infighting. In Louisiana, Ruggles’ commanding officer was Marylander Mansfield Lovell, who had recently been made a major general in charge of defending New Orleans.

In early 1862, Louisiana passed a law that reorganized the state militia, which disrupted Lovell’s defense of New Orleans. Lovell reluctantly ordered Ruggles to Columbus in northeastern Mississippi in February 1862. Lovell found himself at odds with state politicians whose allegiance to states’ rights often conflicted with Confederate operations. Ruggles didn’t stay in Mississippi long. On February 20, he was ordered to defend the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, a vital link protecting Memphis, Mobile, and New Orleans.

As he struggled to master his new duties, Ruggles began a spat with Thomas O. Moore, the governor of Louisiana. It was a war of words that lasted more than a year. Ruggles essentially wanted more authority than Moore was willing to grant. Over the course of the war, some Confederate officers killed each other over real or pretended slights. Ruggles’ disputes never resulted in duels, but he could be abrasive toward others.

After his victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant sought even greater control of Tennessee. By March 1862, Ruggles, then in northern Alabama, complained that his situation was “an unpleasant one, being indeed without any troops at all, except a battalion of Arkansas troops, badly armed.” It was perhaps because of his situation that on March 23, Grant said, “If Ruggles is in command, it would assuredly be a good time to attack.” Grant might have doubted Ruggles’ abilities, but Ruggles was wise to Grant’s movements. He was also concerned that Albert Sidney Johnston was ill-prepared to check the Federal advance into southern Tennessee.

The ensuing bloodshed at Shiloh on April 6-7 exceeded anything Americans had yet experienced. It was during this battle that Ruggles had his finest hour. He again served under General Bragg, whose respect he had won in Florida. Ruggles was placed in command of the 1st Division in Bragg’s Second Corps. Ruggles’ men consisted of Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Texas, and Tennessee troops. On the first day at Shiloh, Ruggles’ men were in the thick of the fighting at the Hornets Nest, where stubborn Yankees withstood horrendous Rebel artillery fire.

Bragg described April 6 as “twelve hours’ incessant fighting, without food.” After a day of savage combat, Federals at the Hornets Nest surrendered, though Grant’s men rallied the next day and regained their lost ground. Ruggles lost almost 1,700 men at Shiloh, roughly 25 percent of his effective force. Ruggles’ son, Edward Seymour Ruggles, was hit in the left arm by a shell. He survived and fought in other bloody battles in the West.

After the fighting at Shiloh, Ruggles again fell ill. In his belated report of the fight, he praised his troops’ steadiness, organization, and good conduct, despite the Southern army’s defeat. He said “the troops of my division displayed almost uniformly great bravery and personal gallantry worthy of veterans in the cause.” The Union Army under Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck was soon on the move against Ruggles and the Confederate Army.

Ruggles had some success in slowing Halleck’s already leisurely advance on Corinth, and won a small victory at Farmington, Miss., just to the east. As Yankees moved farther south, Confederates continued to bicker. Ruggles came into conflict with Lovell, who had lost New Orleans the previous month. Lovell complained to General P.G.T. Beauregard about Ruggles’ supposed authority over the cities of Jackson and Vicksburg, areas that Lovell believed he commanded. Of Ruggles, Lovell complained, “for Heaven’s sake don’t send him into my department, where he will raise a row in a week.” Beauregard chose to send Ruggles to Grenada, Miss., and establish a headquarters for Ruggles’ new command: Gulf Coast Supply Depots Department No. 2. Confederate higher-ups eventually got rid of Lovell, who was charged with incompetence for his loss of New Orleans.

Ruggles’ already impressive record of annoying fellow Confederates included subordinates as well as rival commanders.

Private Robert Patrick, a clerk in the Commissary and Quartermaster departments of the 4th Louisiana Infantry, and known for his account of the war published as Reluctant Rebel, served under Ruggles in 1862. He described his former boss as an “old brute.” Patrick wrote that it was because Ruggles was a longtime officer and New Englander that he “had no conscience nor mercy on any one.” Patrick eventually obtained a transfer away from Ruggles and the miasmatic conditions at Corinth.

In the wake of the loss of New Orleans, Confederates scrambled to defend another vital river town—Memphis. The Rebels, however, were ill prepared to do so. Stationed in northern Mississippi, Ruggles received desperate messages from men such as Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson, the “Swamp Fox of the Confederacy,” and Colonel Thomas H. Rosser, the latter of whom complained “we have no defenses.” On June 6, Memphis fell to the Yankees.

In late June, Ruggles was given yet another command, which put him in charge of a district that included southern Mississippi and East Louisiana. As Federal armies marched farther into the Deep South, they implemented a hard war strategy that involved burning supplies and buildings, razing and stealing crops, and seizing slaves from panicked masters. Armies were also increasingly likely to live off the land, making life harder for civilians struggling to keep their farms and families together. Ruggles and his men put cotton to the torch to keep it out of Yankee hands and impressed slave labor to assist with building projects.

Despite Ruggles’ harsher tactics, he did not appreciate Union generals taking similar actions. On July 15, 1862, Ruggles, then in Louisiana, complained to Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler about the mistreatment of Rebel prisoners and what he saw as the brutal Yankee way of conducting war. Ruggles lamented women and children fleeing from homes, plantations being destroyed, property plundered, and crops laid waste. Such acts, he said, were “crimes against humanity.”

Ruggles, despite being a non-slaveowner, had no sympathy toward the abolitionists. And the fact that he had to write to the notorious anti-slavery politician-general Butler undoubtedly increased his anger. He decried Federal efforts to inaugurate a “servile war, by stimulating the half-civilized African to raise his hand against his master and benefactor, and thus make war upon the Anglo-Saxon race—war on human nature.” Ruggles saw fit to lecture Butler about the nature of revolutions in the United States and South America and how the Federal government had violated the principles of Christian nations. Butler sent back a terse reply, notifying Ruggles that when it came to supposedly mistreating prisoners, it was the “intention of the United States Government to let these men go on their parole and one of them has been gone more than a week.”

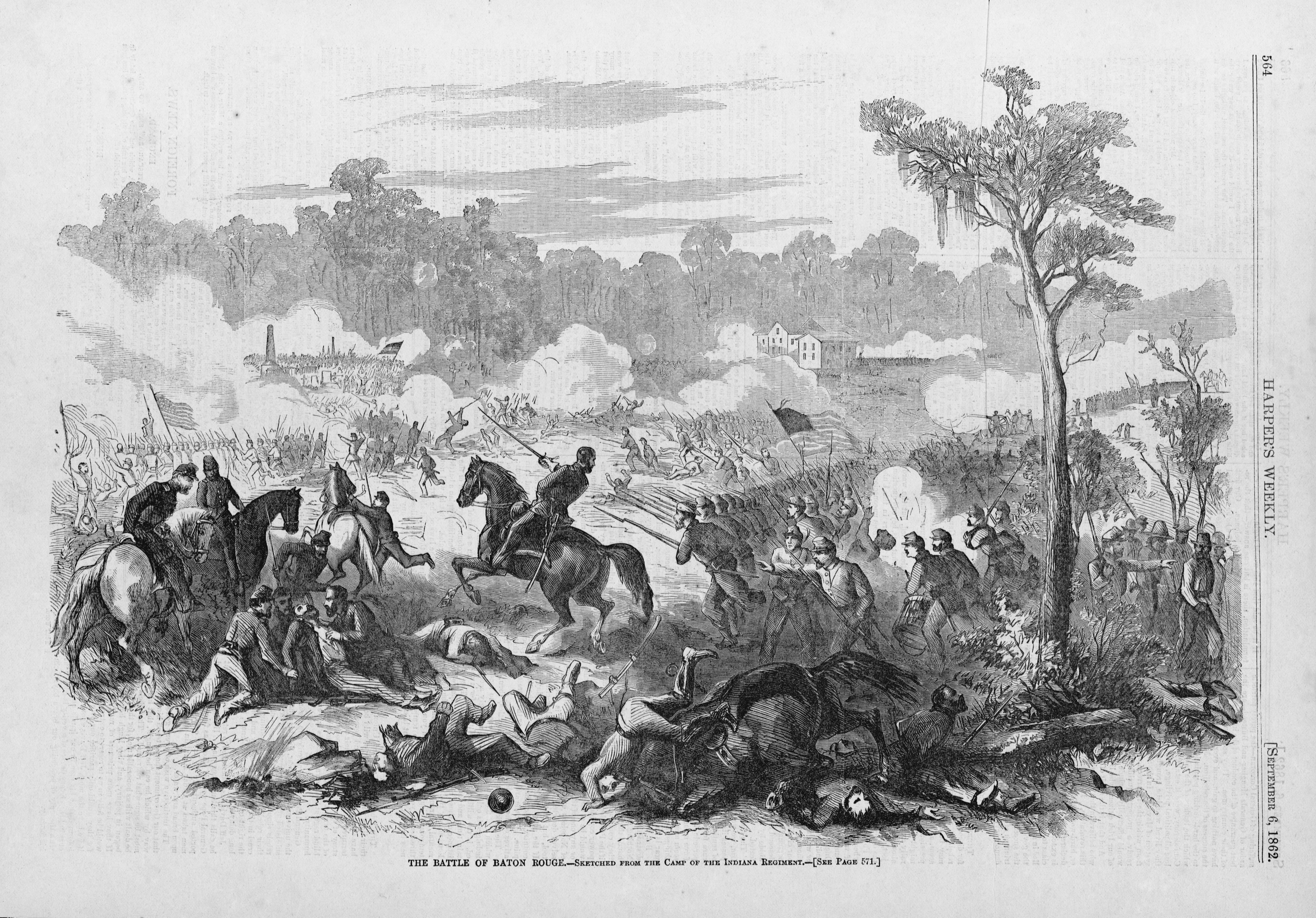

With the capture of New Orleans and Memphis, Federals concentrated on conquering other cities along the Mississippi. Ruggles commanded a small division at the Battle of Baton Rouge, fought on August 5, 1862. The fighting took place on a foggy morning, where Confederates under the overall command of Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge were defeated. Federals could claim the capture of another Rebel capital, though by then Confederate politicians had already moved to Shreveport. Ruggles praised the conduct of officers and the men in his Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi units as “gallant and daring, every movement being performed with characteristic promptitude.” Ruggles lost 215 men.

Baton Rouge was the last significant battle in which Ruggles fought. Rumors of his death circulated for some time. But Ruggles was not dead, and he was eager to protect the rebellion’s hold on the Mississippi. He alerted authorities in Richmond to the need to strengthen fortification at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, La. On October 3, 1862, Ruggles complained to Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn—then at Corinth—that the defenses at Port Hudson there were “far from completion” due to a lack of guns, ammunition, and slave laborers. Given his past differences with Governor Moore, Ruggles doubted Louisiana would send militia to him. Once again, Ruggles trusted more in Confederate officials, not state ones, to help him.

In the fall of 1862, Ruggles was one of the Confederate commanders—along with Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor and others—who dreamed of retaking New Orleans. Such a campaign, however, never materialized. Poor communication and personal sniping at the higher levels continued to undermine Confederate strategy out west. While Rebels bickered, citizens were increasingly worried about slave unrest and the need to have armed men protecting their homes and communities. Some historians believe the “high tide” of the Confederacy happened in the fall of 1862. But in the Far West, the war had gone badly for the rebellion all year.

By 1863, the Confederacy had addressed manpower shortages through two drafts, the second of which included the infamous “Twenty Slave” law of October 1862. This draft allowed for the exemption from military service of one white man on a plantation holding 20 or more slaves. As did those who were critical of the new draft, Ruggles complained about the “protection of the planter interest” at the expense of citizens struggling to feed their families.

During the Vicksburg Campaign, Ruggles was far from the main action. He was reduced to shuffling around small numbers of troops and skirmishing with small Federal detachments in northern Mississippi. Once again, Ruggles found himself in a tense relationship with other officers. He annoyed Mississippi cavalryman Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers, who was operating near Ruggles, as well as Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, who had to remind Ruggles that Vicksburg, not Ruggles’ command, was the priority for getting reinforcements. In May, Ruggles complained of “want of harmony among the commanders of my battalions,” but his forces were in good enough shape to rout 800 Federals at the Battle of Rocky Ford on the Tallahatchie in late June.

The fall of Vicksburg was a shattering blow to the Confederacy, and in August 1863, Ruggles wrote to Benjamin S. Ewell—then serving on Johnston’s staff—to complain that “the spirit of volunteering has ceased to exist” and that there was a “want of patriotic fervor” among his countrymen. In his indictment of Confederate patriotism, he targeted the wealthy slaveholders who were able to purchase substitutes, believing they put their property before the interests of their country. Southern militias also irritated him because he felt they gave able-bodied men a way to stay out of the Confederate Army.

Following the loss of control of the Mississippi River, Confederates had plenty of blame to throw around. In August, James Phelan, a senator from Mississippi called Ruggles “an old, easy, courteous, pleasant nobody!” Maj. Gen. S. A. Hurlbut, a Federal commander in Memphis, also had little respect for Ruggles, saying he “will not fight, but run.” Ruggles was not the kind of commander to run from a fight, but clearly, by the end of 1863, he could do little good for Confederates in Mississippi.

By 1864, Ruggles was without a major field command. He returned to the East, where Jefferson Davis gave him a position as commissary for prisoners of war in Georgia. Ruggles, however, longed to return to the field. In February 1865, a town council in Fredericksburg noted “with pride and pleasure” Ruggles’ “steady devotion to the Confederate cause” and appreciated his “distinguished and arduous services.” His lack of a field command left the council “mortified.” In March 1865, when asked by Jefferson Davis about Ruggles’ possible promotion to major general, Robert E. Lee, as diplomatic as ever, said Ruggles was “an officer of standing & truth, but I know of no Division to which he can be assigned.” Once again, Ruggles had been frustrated by a superior officer.

Lee’s surrender did not put an end to Ruggles’ family drama. After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Ruggles’ son Mortimer, then in Virginia, chanced upon the fleeing John Wilkes Booth and helped him escape across the Rappahannock into Port Royal. Daniel Ruggles had not been involved, but his family’s complicity in the assassination further solidified their Rebel credentials.

After the war, Daniel Ruggles farmed in Texas for a few years, but he spent most of his postwar life in Fredericksburg. In 1866, he was in the local news when his horse, “Shiloh,” was stolen, though the animal was found later in Warrenton. He served on the board of regents for West Point. He was also an inventor who petitioned Congress for funds to develop a system for producing precipitation through explosions in the atmosphere. Ruggles thought it no coincidence that Civil War battles were often fought in rainy weather.

Daniel Ruggles died in Fredericksburg on June 1, 1897, at the age of 87. A local paper remembered him as “much respected and loved by our people,” adding that he was a “gentleman of the most polished manner and pleasing address, and a citizen of unblemished character.” The general’s life and Civil War career was more complicated than that. As a general, Ruggles was a capable tactician and administrator, but in a Western Theater plagued by difficult commanders, Ruggles made enemies easily. Even so, he managed to stay on the good side of Bragg and President Davis.

Ruggles is one of six generals buried in the Confederate cemetery in Fredericksburg. His archive is as scattered as his career. His military and personal papers are housed at University of Texas at Austin, Louisiana State University, and Duke, just to name a few. His story is not very well known, but it sheds much light on the loyalties and personalities of the Confederate high command in the West, where the South—best by logistical challenges, incompetent leadership, and political infighting—lost the war.

_____

Ruggles’ Grand Battery

Daniel Ruggles’ most famous Civil War moment came on the first day of the Battle of Shiloh, April 6, 1862, when he is credited with organizing between 53 and 62 cannons, depending on the source, to deliver massive artillery barrages at a position in the center of the Union line since called the Hornets Nest. Federal troops under Union generals W.H.L. Wallace and Benjamin Prentiss had formed a defensive line on the north side of Duncan Field in what is termed the “Sunken Road,” even though it was not really sunken. Eleven Confederate charges had failed to break the Union line. About 4 p.m., the Southerners began massing the amalgamation of mixed-caliber batteries from Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama. The largest concentration of artillery ever seen in North America up to that time soon began pounding the Union forces across Duncan Field with shot and shell.

A Union officer described the barrage as a “mighty hurricane sweeping everything before it.” But the attack was not one-sided. Union artillery responded, and for a while, the Confederates still proved unable to dislodge the Yankees from their positions. The Union flanks gave way, however, a retreat had begun even before the Rebel artillery opened up, and only the troops in the center were left to continue the fight against the Confederates. As darkness began to fall, Southern troops captured the position and about 2,250 Federal troops.

Other Confederate officers also claimed credit for organizing the row of deadly fieldpieces, including Maj. Gen. Hardee’s chief of artillery, Major Francis Shoup, and Brig. Gen. James Trudeau, and it was likely a team effort. But the term “Ruggles’ Grand Battery” is still synonymous with a roaring line of cannons that helped break the Union army’s Hornets Nest line. –C.W.

Colin Woodward is the author of Marching Masters: Slavery Race, and the Confederate Army during the Civil War. He is currently working on a book about Johnny Cash. An archivist who lives in Richmond, Va., he is host of the American Rambler history podcast.

This story appeared in the April 2020 issue of Civil War Times.