An Afghan War veteran laments the disappearance of hallowed landscape

Wearing blue jeans, a black T-shirt, a camouflage ball cap and a scowl, Stan Hutson stands among boulders in the infamous Slaughter Pen at Stones River National Battlefield. The 43-year-old Afghan War veteran can relate like few of us can to to the soldiers who fought on this central Tennessee battlefield in the winter of 1862-63.

“Those guys are like brothers to me,” says Hutson, who recalls comrades who were killed during his one-year tour in Afghanistan with the U.S. Army. Those horrible memories, the Alabama native admits, left him with survivor’s guilt.

On December 31, 1862, soldiers from four regiments—men and boys from Indiana, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Ohio—valiantly held out for nearly two hours in the labyrinth of limestone that Hutson surveys. When the Federals saw their dead and wounded bleeding in the natural trenches, they were reminded of animal slaughter pens. The name—the “Slaughter Pen”—stuck.

For many, a few minutes in the Slaughter Pen can be an otherworldly experience, but Hutson, whose ancestors fought on both sides at Stones River, doesn’t feel the vibe. He blames the distracting hum of cars nearby in traffic-choked Murfreesboro, Tenn., and the encroachment of 21st-century development.

“It’s all gone,” he says, referring to core Stones River battlefield. Remorseless developers have pounded the life out of much of this great battlefield, where more than 24,000 souls became casualties in one of the bloodiest fights of the Civil War.

Our aim on this deep-blue sky afternoon is to find where five of them fought and received their mortal wounds. What would we see on this battlefield lost?

Murfreesboro, the site of the Stones River battlefield, is about 30 miles southeast of Nashville. Only 680 acres, about 15 percent, of the vast battlefield is preserved by the National Park Service. Besides the Slaughter Pen, a beautiful national cemetery and ground along the strategic Nashville Pike are among acreage within the park.

With the landscape dramatically altered, or destroyed, it’s often difficult to determine where soldiers fought outside the park boundaries. Few historical markers beyond NPS-maintained land denote battlefield sites, such as the scene of opening action of the battle, now within earshot of the drone of traffic on U.S. Interstate 24. Consequently, not only is the battlefield disappearing, but knowledge of the wartime landscape is too.

“I’m sick about it,” says Hutson, who, as a National Park Service maintenance worker at Stones River, has witnessed the destruction caused by development around the park.

On his personal time, Hutson takes his Fisher F75 metal detector to construction sites and elsewhere in the area to hunt for battle relics. While detecting on a site prepped for the construction of apartments, he discovered three Confederate buttons and seven ball buttons. Some even had fragile pieces of a gray coat attached. “A find of a lifetime,” he tells me.

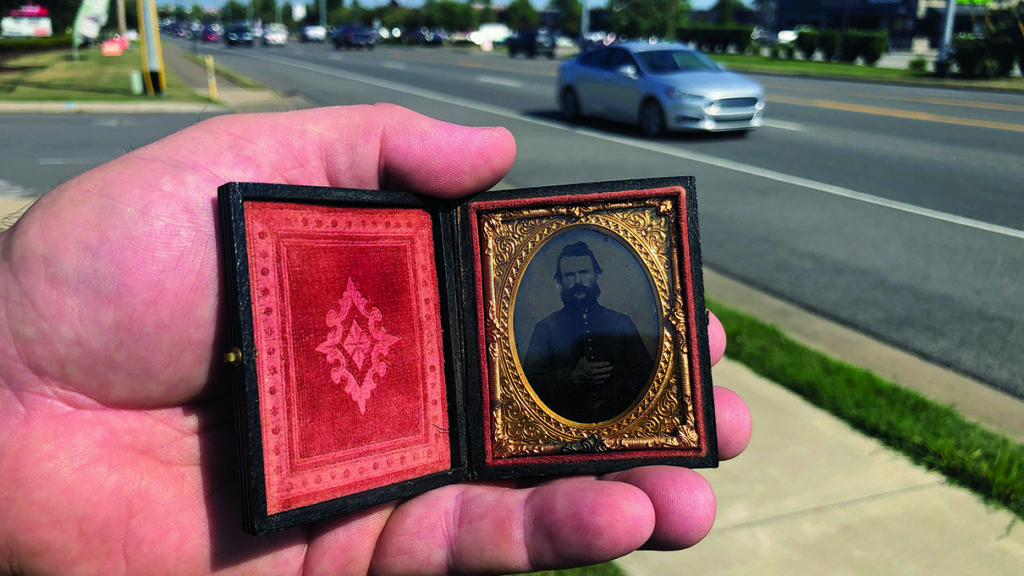

ear that site, Hutson holds a 1/9-plate tintype he acquired of Julius Berdan Waite, a 30-year-old private in Battery E of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery. “Probably an image he sent to his wife,” says Huston. In a Napoleonic pose, a bushy-bearded Waite stares straight ahead, the thumb of his large hand tucked inside his military jacket. As evidence of the fierceness of the fighting, he was among several in his battery to be killed during the opening fighting on the frigid morning.

Hutson believes we stand in the general area of Waite’s death, a few feet from busy, five-lane Old Fort Parkway, and near a dental clinic, convenience store, and another apartment complex construction site. About 15 years ago, the area was largely open fields.

Leaving the scene, we drive down Gresham Lane, a two-lane, blacktop road that was a skinny, dirt lane during the war. Hutson points to where we are on a map: The ridgeline the Yankees briefly held December 31 is the only feature one can easily find on this decimated battlefield landscape. We maneuver down another traffic-clogged road, past a chicken restaurant, where Hutson uncovered a 6-pound Confederate solid shot buried in three inches of soil behind a dumpster. It was fired from an 1841 6-pounder field gun, he says.

Surrounded by ugly suburbia, we glide into a space in a bank parking lot. On the horizon, a giant crane preys on the massive frame of a building under construction.

While leading his men at roughly 9 a.m. on December 31, Union Brig. Gen. Joshua Sill was killed in this area by a bullet that struck him in the face and penetrated his brain. The 31-year-old commander died wearing General Phil Sheridan’s jacket, mistakenly picked up by Sill during a military conference earlier that day. The men, good friends, were roommates at West Point. “No man in the entire army, I believe, was so much admired, respected, and beloved by inferiors as well as superiors in rank as was General Sill,” a Union officer said afterward. Sill’s death site is unmarked, forgotten.

From another parking lot, Hutson points out the general area where Abner Columbus Ball, a private in Company G of the 22nd Alabama, was killed on December 31, the day after his 35th birthday. He left behind a wife and four children. Did Ball die by what’s now a tire store? Was he orginally buried by the gas pumps at the convenience store? As we survey the “hallowed ground,” a man stops to ask where he can find the cable company. Battlefield buzz kill, for sure.

At another convenience store we stand on paved-over ground. On New Year’s Eve 1862, this was part of Hell’s Half Acre, where William Hazen’s brigade of soldiers from Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, and Ohio held off repeated assaults.

In or near Hell’s Half-Acre, John Penland, a 45-year-old private in the 57th Indiana, was severely wounded when a cannon ball grazed his stomach. After examining his map, Hutson figures the married father of nine children was shot “between the Dollar General store and that Gerber’s sign.” Penland, who had three sons in the Union Army, held in his intestines and walked a mile to his camp. He died from infection and fever on January 4, 1863.

Even at national park’a doorstep, nearly within site of the Slaughter Pen, the 21st century looms. Until 2017, this land upon which Mississippians, Tennesseans, and Alabamians advanced was mostly open field and a few houses. In the attack, James L. Autry, a lieutenant colonel in the 27th Mississippi, was killed. The 31-year-old lawyer and politician was survived by a wife named Jeannie and a 3-year-old son, James II. Now his death site is occupied by a 116-bed hospital and a parking lot. “They want to leave nothing here,” Hutson says. “Nothing.” At least two history lovers’ hearts ache this day. But through loss sometimes comes renewal.

Back at the national park, shortly before we examine the beautiful Hazen Brigade monument, a train chugs past the Stones River National Cemetery. The engineer lets out a blast of the train’s horn—a sign of respect, Hutson believes, for the more than 6,000 Federal soldiers buried there. ✯

John Banks is the author of the popular John Banks’ Civil War blog. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.

This column appeared in the February 2020 issue of Civil War Times.