A Maryland family helped nurse wounded Rutherford B. Hayes

No historical markers can be found on the circa-1840, red-brick house in Middletown, Md., where 23rd Ohio lieutenant colonel and future U.S. president Rutherford B. Hayes recovered from his South Mountain battlefield wounds. And, according to the residence’s longtime current owners, few people inquire with them about its Civil War significance.

“Several years ago, a man from West Virginia came and took some pictures of the place,” said 86-year-old Donald Shank, who has lived in the small, unassuming house at 504 West Main Street with his wife, Lois, since they were married in 1960. “But that’s about it.”

In 2016, visitors from the Hayes Presidential Library—including some of the former Union officer’s descendants—visited Middletown, where they posed on the steps of the wartime Zion Lutheran Church with near-life-sized, cardboard cutouts of Rutherford and Lucy Hayes. The group viewed the Shanks’ house from the outside only.

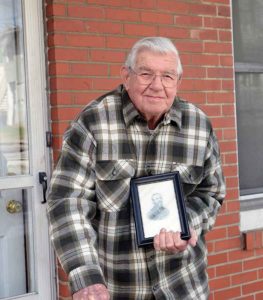

In the late 19th or early 20th century, one of Hayes’ sons visited the house where his father convalesced during the Civil War. He presented to its owner, Shank’s grandfather, an 1865 image of his father in uniform. During my visit, Shank proudly posed with that photograph, which shows Hayes as a general, a rank he attained in the fall of 1864. In period writing on the reverse, an unknown individual wrote: “Of the presidents of the United States, from Washington to Wilson, fifteen served as officers in battle; but with the exception of James Monroe, when serving as a lieutenant in Trenton, none other than General Hayes was wounded in battle.”

Donald Shank’s ties to the house are especially strong: He and his three sisters were born in an upstairs bedroom, perhaps the same room where Hayes was tended to by “Lemonade Lucy,” his doting wife, so nicknamed for her staunch support of the temperance movement. Although he has an interest in history, Donald doesn’t give much thought to his family’s connection to the story of the 19th president of the United States. Neither does Lois, 80. “To us,” said Donald, a lifetime Maryland resident who served in the U.S. Army from 1953-55, “Hayes is just another person.”

But, oh, if the walls of Shanks’ house could talk. What a story it could tell about Hayes. It’s a love story, really.

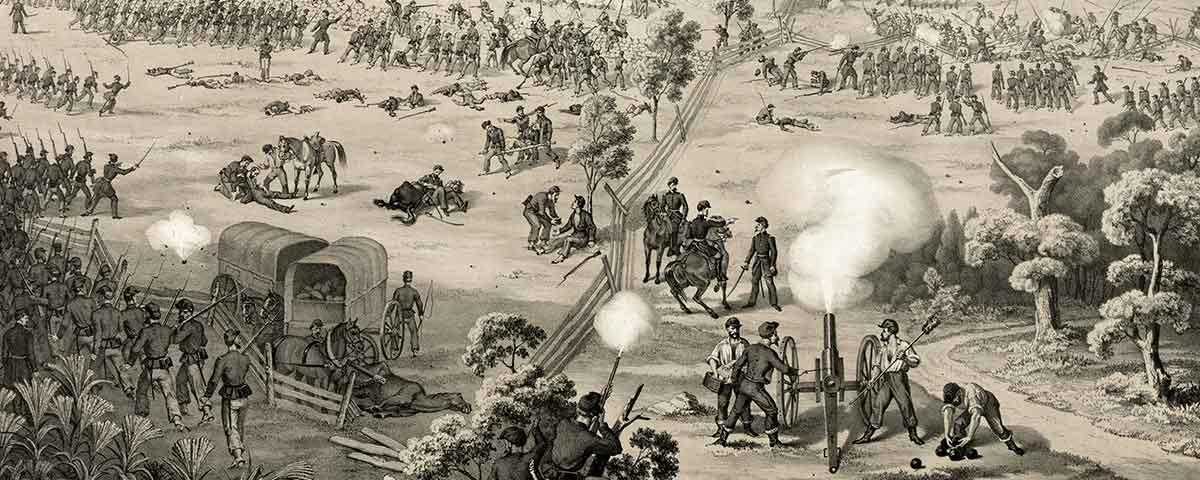

On September 14, 1862, while leading his troops at Fox’s Gap during the Battle of South Mountain, Rutherford Birchard Hayes was seriously wounded. “Just as I gave the command to charge,” the 39-year-old officer wrote in his diary, “I felt a stunning blow and found a musket ball had struck my left arm just above the elbow. Fearing that an artery might be cut, I asked a soldier near me to tie my handkerchief above the wound. I soon felt weak, faint and sick at the stomach.”

While he lay in the field, Hayes had a “considerable talk” with a wounded Confederate. “I gave him messages for my wife and friends in case I should not get up,” he wrote. “We were right jolly and friendly; it was by no means an unpleasant experience.” Finally, Hayes was carried out of range of Rebel fire, placed behind a big log and given a canteen of water.

After his wound was dressed, Hayes staggered a half-mile down the mountain to the small house of a widow named Elizabeth Koogle, remaining there for two or three hours. Still faint from loss of blood, he was taken by ambulance three or four miles or so into Middletown, called “Little Massachusetts” because of its pro-Union sentiment. Churches, private homes, barns, and other buildings there were thrown open for Union wounded. Hayes’ association with local merchant Jacob Rudy, his wife Elizabeth, and their two sons and five daughters began that night.

So, too, did a mutual admiration society.

While he recovered, Hayes grew quite fond of the Rudys—he felt “as snug as a bug in a rug” while he lay in an upstairs room in their house. “I am comfortably at home,” he wrote his mother the day after he was wounded, “with a very kind and attentive family here named Rudy.”

Two days after he was wounded, Hayes was free of pain when he lay still. He delighted in sampling Elizabeth Rudy’s currant jellies, and the family’s youngest son, 8-year-old Charlie, enjoyed describing for Hayes the troops as they passed their house on the busy National Pike. “Charlie, you live on a street that is much traveled,” Hayes said. “Oh, it isn’t always so,” the youngster replied. “It’s only when the war comes.”

In April 1877, a lengthy, and remarkably detailed, account of Hayes’ stay with the Rudys was published in the New York Herald. Under the headlines “Reminiscences of His Treatment With A Friendly Family” and “A Real Love Story,” Rudy’s wife and daughters Kate and Ella recounted their experiences with Hayes, sworn in as 19th president the previous month.

When the ambulance carrying Hayes and army surgeon Joseph Webb, his brother-in-law, arrived about sunset at the Rudy house on the National Pike, near the western edge of town, the family was in the midst of their own health crisis. Twenty-one-year-old Daniel Webster Rudy, the couple’s eldest son, was seriously ill with smallpox, and daughters Laura, 11, and Ella, 9, had scarlet fever.

Still, the Rudys welcomed the disheveled and badly wounded Hayes, whose uniform was spattered with dust and mud. The officer was carried up the narrow staircase and placed in a bed in a room next to the one where Daniel lay ill. Webb and his brother, James, also an army surgeon, tended to Hayes’ wounded arm. A highly respected local physician named Charles Baer aided them. Two black servants, who accompanied Hayes and Joseph Webb in the ambulance to Middletown, slept on the floor of Daniel’s room.

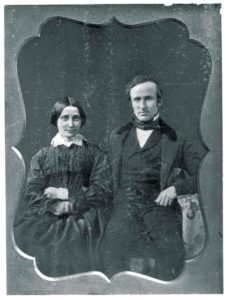

When Lucy Hayes, the lieutenant colonel’s 31-year-old wife, arrived from Ohio more than a week after the Battle of South Mountain, Elizabeth Rudy made an instant connection with the mother of five young sons. “The moment she crossed our threshold,” she told the reporter, “I knew she was a good woman and a natural lady….She was relieved to know that his wound was not so dangerous as she had imagined it.”

Rutherford Hayes never had a cross word to say about the Rebels. “Though he suffered constantly and got little sleep for a week and longer,” Ella Rudy said, “he was always cheerful. He not only wouldn’t be cross—he wouldn’t allow any extra trouble to be taken on his account. Mother used to ask him if she could not ‘do something’ for him. He always thanked her, but said no….”

In late September, Hayes was well enough to walk about Middletown. He preferred the unpaved south side of the street, sometimes sloshing through shoe-deep mud, instead of the paved north side, causing the town’s tongues to wag. In early October, he and his wife visited the Lutheran Church cemetery, where they could watch the sun set and admire gorgeous fall foliage. On his 40th birthday on October 4, Hayes and Lucy traveled with Jacob Rudy and two other men to the South Mountain battlefield. “Hunted up the graves of our gallant boys,” he wrote in his diary. Later that month, Hayes finally returned to his home in Cincinnati with his wife.

Weeks after Hayes’ departure, every member of the Rudy family contracted smallpox. Charlie died from the disease on November 4.

In the summer of 1864, with the Union army in western Maryland to check Jubal Early’s advance into the state, Hayes found time to visit with the Rudys. “They were so kind and cordial,” he wrote in a letter to Lucy. “They all inquired after you. The girls have grown pretty—quite pretty.”

Captain Rudy, who would die on Christmas Day in 1876, had not forgotten about the soldier he took into his home in 1862. “Mr. Rudy said if I was wounded,” Hayes told his wife, “he would come a hundred miles to get me.”

Clearly, Hayes remained close to the hearts of Elizabeth, Kate, and Ella Rudy, too. “So you all fell in love with the patient Colonel?” the reporter asked Elizabeth Rudy during his 1877 visit.

“We fell in love with him directly,” she replied.

John Banks is author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers, both by The History Press. He also is author of a popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). Banks lives in Nashville, Tenn.