A day with preservationist Clark ‘Bud’ Hall at his beloved Brandy Station

To understand Clark “Bud” Hall’s passion for Brandy Station, where the war’s biggest cavalry battle was fought, you have to explore his battlefield with him. “Brandy” is a living thing for the 74-year-old former Marine and ex-FBI agent—a fragile place worth vigorously defending, nurturing, documenting, and, yes, loving.

“I have spent more time there,” Hall tells me, “than I have anywhere else in the world.”

Early on a late-fall morning, before we closely examine his beloved 1863 battleground, Hall and I visit several other Civil War sites in Culpeper County, Va., in his gray truck. “Semper Fidelis,” his license plate holder reads—“Always Faithful,” the motto of the U.S. Marine Corps. One of the country’s leading battlefield preservationists, Hall rents a house in the town of Culpeper, allowing the Mississippi native easy access to the area’s rich Civil War history. “He is one of those rare people that when he drives and travels, he sees in his mind’s eye constantly a landscape that is gone,” says historian John Hennessy, a longtime friend of Hall. “He sees 1863.”

As we drive on Culpeper County’s back roads, an early morning rain finally yields to deep-blue sky and scattered clouds. Hall seems to know the location of the remains of every Civil War gun pit; the importance of every ford; the story of every wartime house.

“See that high ground?” Hall says, gesturing to a ridge near Clark Mountain, the Army of Northern Virginia’s nerve center from November 1863-May 1864. “That’s where the Confederate camps were.” As we ascend a bumpy, narrow road to the top of the unspoiled mountain, Hall identifies traces of wartime roads peeking through leaves. The view from the 1,082-foot summit is spectacular. A Confederate signal station once stood on this land, now privately owned.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]We share a collective responsibility to secure and save these sacred fields[/quote]

On a clear day, you can see Harpers Ferry Gap, roughly 70 miles north in West Virginia. In the near distance, Cedar Mountain looms over the site of the August 1862 battle.

Near the Rapidan River to the east sits a beautiful white house well out of view. It was Powhatan Robinson’s home, “Struan,” used by Union Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren as a headquarters and by the Army of the Potomac as a hospital in the aftermath of the Battle of Morton Ford’s in early February 1864. Hall knows the 1840 house and its owner well; its expansive porch is a perfect place for a man with a full flask and an active imagination.

Miles away, we see Stony Point, where the “Nutmeggers” of the 14th Connecticut camped before the regiment suffered severe casualties at Morton’s Ford. In all, 18 Civil War battlefields in Virginia’s Piedmont can be seen from the awe-inspiring summit of Clark Mountain. “He stands on top of that mountain,” says Hennessy, “and sees everything that matters to him.”

What matters most to Hall, of course, lies 15 miles north as the crow flies.

Bud Hall’s love affair with “Brandy” began in 1984. He was then unit chief of the FBI’s Organized Crime section in Washington, D.C. On weekends, he visited the region’s many Civil War sites. Picturesque, pristine, and largely unmarked, Brandy Station—little more than an hour’s drive southwest of Washington—became his favorite. Hall wanted to know everything about the Battle of Brandy Station, fought on June 9, 1863, and the battlefield’s rolling fields and hollows, so he plunged into its history.

Yes, Hall obsesses over his battleground and other hallowed ground in Culpeper County. But who could argue against his explanation for why these places are important? “Young Americans fought, bled, and died on our Civil War battlefields,” the Vietnam veteran told me, “and I profoundly believe we share a collective responsibility to secure and save these sacred fields.”

As Hall and I stand by ourselves on Fleetwood Hill, viciously contested during the 1863 battle, he says it’s impossible to imagine the killing, screaming, and dying. More than 18,000 horsemen fought at “Brandy,” making it the largest cavalry battle in American history. On a large hill in the distance, we can see “Beauregard,” the fabulous, circa-1840s brick mansion of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s adjutant, James Barbour.

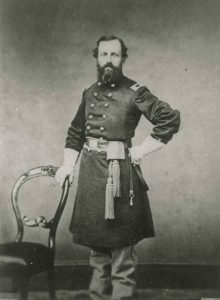

“More men fought and died here at Brandy Station,” Hall says, “than anywhere else in war-torn Culpeper County.” Busy traffic on nearby James Madison Highway drones on as he talks about two of them: Private George Henry Williams of the 12th Virginia Cavalry and Lt. Col. Virgil Broderick of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry. For Hall, who’s been researching and writing a book-length, detailed tactical narrative about Brandy Station since 1990, the soldiers’ stories are especially meaningful. Many of his ancestors served the Confederacy, “a futile, misguided cause,” Hall says. He has a deep respect, however, for men in blue and gray.

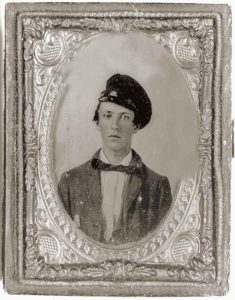

In 1861, 17-year-old Williams pleaded with his widowed mother to grant him permission to join the Confederate Army. He enlisted as a private in the 10th Virginia Infantry; later, he transferred to the cavalry. Like many soldiers, George desperately missed his family. “You don’t know what pleasure it gives me,” he wrote in a letter, “to hear from home.” Three days before the Battle of Brandy Station, Williams wrote to his sister: “We will have work to do in a few days,” he said, adding, “the Yanks are just across the river.”

When the Federals threatened to seize Fleetwood Hill that late-spring day in 1863, the 12th Virginia Cavalry was thrust into the fray by Hall’s hero, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Arriving on the northern slope of Fleetwood, Williams quickly knocked a Union trooper from his horse in a sword fight, capturing him. As he marched his captive to the rear at the point of his saber, the prisoner suddenly pulled out a small pistol and shot the teenager between the eyes, killing him instantly.

After the battle, George’s body was identified by his grief-stricken brother, James, a lieutenant in Stuart’s Horse Artillery. Williams was initially buried on Fleetwood Hill, then removed two months later by his brother and reburied in a cemetery in Woodstock, Va.

Broderick, a farmer in civilian life, charged up Fleetwood Hill with the 1st New Jersey, and Confederates quickly surrounded him and ordered his surrender. The 30-year-old lieutenant colonel refused and the Rebels killed him. He is buried at Culpeper National Cemetery. Hall often visits his grave.

Today, the ground where Williams, Broderick, and so many others fought and died is an open, rolling field. Impressive markers note the significance of the site. It wasn’t always so. An ugly, modern mansion once dominated the crest of Fleetwood Hill. When the private property was put up for sale, Hall, the American Battlefield Trust, and other preservationists lay in wait to buy it. When the eyesore was finally torn down in 2014, Hall was given the mansion’s front-door lock as a well-earned trophy of his war to save hallowed ground.

As we cut across the battlefield to another stop, Hall spots something suspicious about a half-mile away. “What is that figure?” he asks. “Is it moving?” No, it wasn’t human, certainly not a relic hunter, an anathema to Hall. He visits his battlefield every day he’s in the area, just to make sure “Brandy” is OK. “I am the Brandy Station police force, a force of one,” he says, chuckling. “The pay is not real great.”

We drive down Beverly’s Ford Road, leaving a gust of leaves in our wake. At a quiet dead end, we find one of Hall’s favorite spots on the battlefield, a place he has visited “hundreds and hundreds of times,” almost always alone. Here at 4:30 a.m. on June 9, 1863, Lieutenant Henry Cutler of the 8th New York Cavalry charged up the ford road across an open plain at the head of his men. He soon fell mortally wounded, the first of 55,000 casualties in what became the Gettysburg Campaign.

At Cutler’s funeral days later in Avon, N.Y., a “deep solemnity” was “stamped on every brow.” The lieutenant, described as a “young man of great promise,” was 26. When Hall first saw Cutler’s gravesite in New York, it was badly eroded, the tombstone severely neglected. He was the catalyst for getting it fixed.

At the crest of Buford’s Knoll, the prettiest site on the battlefield, no modern intrusions mar the view. Perhaps that’s why Hall often comes here to sit and to think. Sometimes it’s difficult for him to leave. No wonder. Hall was the driving force in saving this ground, once targeted by a developer for an auto racing track. “I’d rather be out here,” he says, “than eat.”

Before Hall and I complete our tour of his battlefield, we must visit “Farley,” a beautifully restored mansion that served as VI Corps commander John Sedgwick’s headquarters during the Army of the Potomac’s winter encampment here in 1863-64. Perhaps no home at Brandy Station has as much meaning to Hall as the privately owned property. He proposed at Farley to the love of his life, Deborah Whittier Fitts. A longtime journalist with a passion for the Civil War, she died of breast cancer in 2008, a wound that remains unhealed for Hall.

“Deb loved this place,” he says.

She undoubtedly would be pleased, then, that Hall’s work preserving their beloved “Brandy,” and other Civil War sites in Culpeper County, does not go unnoticed. Hennessy ticks off land Hall was instrumental in saving, hundreds of acres under easement from Kelly’s Ford to Morton’s Ford. “He has given us,” he says, “one of the most remarkable preservation accomplishments of our generation.”

“It is,” Hennessy adds with great admiration, “a gift to the world.” ✯

John Banks is the author of the popular John Banks Civil War Blog. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.