Confederate general Earl Van Dorn would hardly recognize the neighborhood central to the story of the end of his life

A skate park, pool supply store, and a rusty chain-link fence that commands little respect surround White Hall, the mansion in Spring Hill, Tenn., where Major General Earl Van Dorn, Army of Mississippi cavalry commander, made his headquarters beginning in March 1863. Although the Civil War-era home of physician and planter Aaron White retains most of its old charm, it clearly needs fresh coats of white paint. Large maples and a massive, ancient oak tree nearly obscure the view of the 1844 mansion from busy Duplex Road. “Private Property, No Trespassing,” warns a small sign near the front door.

A half-mile away, another mansion where Van Dorn also made his headquarters stands atop a slope overlooking Columbia Pike. Built in 1853, it is bordered by a ranch house, a carport, and the rest of the campus of the Tennessee Children’s Home, which owns the nearly two-acre property. Known

as Ferguson Hall, the Civil War-era home of Martin Cheairs boasts of nearly 8,000 square feet, four large bedrooms, a magnificent, freestanding spiral staircase, eight fireplaces, and 12-foot ceilings. But it, too, could use a dose of TLC.

Each mansion is for sale, with asking prices well north of $1 million. And each has a dark, ugly past: 155 years ago, White Hall was site of the beginning of a scandalous affair between the 42-year-old Van Dorn and a married woman 17 years his junior. Cheairs’ stately home was the site of the general’s murder.

Perhaps no one knows more about Earl Van Dorn than Bridget Smith, author of Where Elephants Fought, a historical novel about the twists and turns of his sordid life and death. A 53-year-old Tennessee native, Smith has devoted more than 20 years researching the man she calls a “typical 1860s frat boy.”

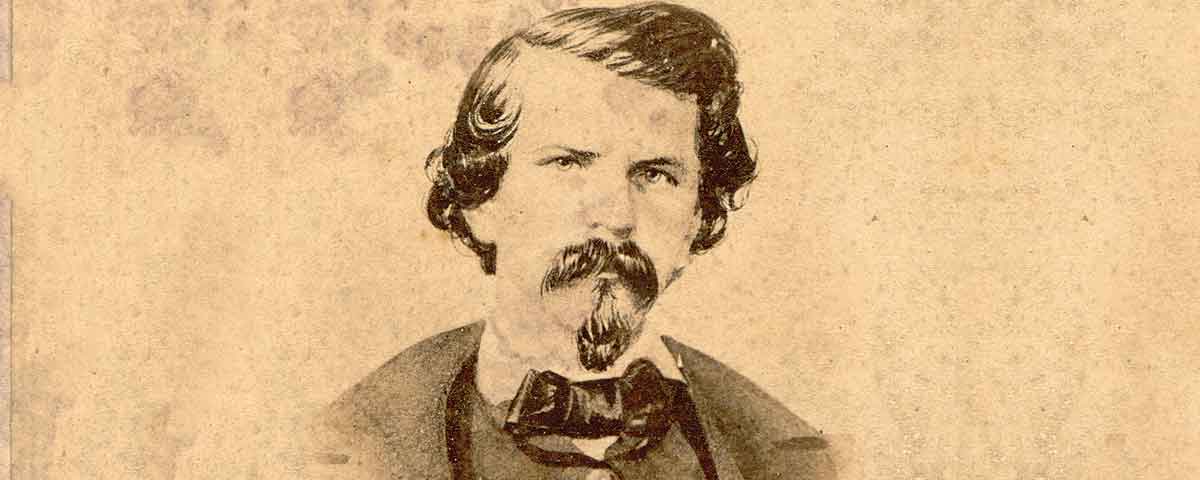

A Mississippian who graduated 52nd of 56 in the West Point Class of 1842, Van Dorn was one of the war’s most flamboyant and compelling personalities. He enjoyed poetry and was an accomplished painter and horseman. A Mexican War veteran, Van Dorn was the grand-nephew of President Andrew Jackson, who helped secure an appointment for him at the academy. During the Civil War, he quickly rose from army brigadier general to major general before becoming a cavalry commander. His battlefield results, mostly in the Western Theater, were mixed. In his greatest triumph, Van Dorn’s cavalry forces destroyed more than $1 million of Union supplies on December 20, 1862, at Holly Springs, Miss., disrupting Ulysses Grant’s operations against Vicksburg, Miss. “He was,” says Smith, “always looking for fame and glory.”

Although Van Dorn and his wife, Caroline—“a girlish-looking little woman” whom he married in 1843 when she was 16—had two children together, the general was far from a devoted partner. He worked overtime to earn one of the all-time great nicknames, the “terror of ugly husbands and nervous papas.”

Smith—who is writing a nonfiction companion to Where Elephants Fought and working on a movie about the general—has documented Van Dorn’s dalliances. There was the 18-year-old in Vicksburg. And a woman in Texas—a “laundress” probably of, ahem, low social standing—with whom he had three children. For Van Dorn, Smith says, there was “a constant flow of women.”

A reporter traveling with him in 1863 also took notice of Van Dorn’s obsession with the opposite sex, writing of the general’s conversation with a “buxom widow of twenty” in Spring Hill: “After the lively little creature had congratulated him upon his recent success, she closed by saying: ‘General, you are older than I am, but let me give you a little advice—let the women alone until the war is over.’

‘My God, madam! replied he, ‘I cannot do that, for it is all I am fighting for. I hate all men and were it not for the women, I should not fight at all; besides, if I adopted your generous advice, I would not now be speaking to you.’”

Van Dorn’s constant flow of women ended in Tennessee, 35 miles south of Nashville. The beginning of the end came at White Hall.

After Joe Ed and Jean Gaddes purchased White Hall in 1992, the couple labored on the antebellum house, saving almost all the original structure. “We’ve worked on this all we could,” says Jean, 76. “We sure would like to see someone buy it who appreciates its history.”

Surprisingly, the couple have never lived in White Hall, instead holding weddings, club meetings, high school reunions, and holiday events in the mansion by appointment only. They relish entertaining visitors with tales of its remarkable past. On the mansion lawn in late November 1864, Nathan Bedford Forest’s cavalrymen were served fried chicken by the White family, and the house was a Confederate hospital after the Battle of Franklin. But it’s a visit in the spring of 1863 that drives this story.

Eager to meet Earl Van Dorn, 25-year-old Jessie Peters brushed by Mrs. White and headed for the general’s room on the second floor of White Hall. Peters was the beautiful third wife of George Peters, a 51-year-old doctor, farmer, and politician. Jessie’s visit to White Hall led to gossip of an affair and incensed the Whites, who suggested the general move his headquarters elsewhere. Van Dorn complied, taking his troopers to Cheairs’ mansion nearby. Soon, Dr. Peters got word of the “distressing affair.”

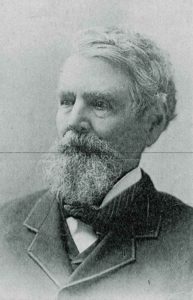

Although facts of Van Dorn’s murder remain in dispute, this we know for sure: On the morning of May 7, 1863, in a first-floor room in Cheairs’ mansion, Dr. Peters shot the general in the head with a single-shot pocket pistol, killing him. The gunshot apparently was muffled, so Van Dorn’s staff outside was unaware the general had been shot until well after the fact. With aid of a pass signed by Van Dorn, Peters escaped, riding a horse through Confederate lines to Union-held Nashville, where he surrendered. The doctor readily admitted his guilt, giving Federal authorities a detailed account of the shooting.

Peters said he told Van Dorn, “If you don’t comply with my demands I will instantly blow your brains out.” The general, according to Peters, then replied, “You d—d cowardly dog, take that door, or I will kick you out of it.” Peters then drew his pistol and fired, recalling that Van Dorn “received the shot in the left side of his head just above the ear, killing him instantly.” Peters was never convicted of the killing.

If you believe Van Dorn’s staff, the general was “entirely unconscious of any meditated hostility on the part of Dr. Peters.” The general’s rumored involvement with Jessie? Rubbish, they said. Author Smith believes Van Dorn’s affair with a member of the Peters family indeed was the catalyst for the dastardly deed. But her research points to the general’s seduction of 15-year-old Clara Peters—the doctor’s daughter from his second marriage—as Peters’ motivation to commit murder. In another twist to this ugly tale, Smith has evidence suggesting Van Dorn impregnated Clara, whom the family later had stashed away in a Missouri convent, where she became a nun.

Coverage of Van Dorn’s death was mostly slanted toward the allegiance of the publication. “The murder of Gen. Van Dorn,” the Montgomery (Ala.) Advertiser wrote, “will strike a thrill of horror through the whole South…” But Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Weekly Herald had the most biting critique of the dead general: “This man was a conspicuous traitor. He had not a particle of moral principle, deceiving alike, friend and foe. He was false to his country, his God, and his fellow men. A violent death was the natural consequence of a life stained all over with violence.”

Laura Wayman, a 64-year-old Michigan native, has an intimate knowledge of the room where Van Dorn was killed. From 2003-2005, she lived alone in Ferguson Hall, steps from her job as an administrator for the Tennessee Children’s Home. “No,” she says unprompted, “I never saw any ghosts.” Over the years, the mansion has served as a military academy, housing for the children’s home and a residence for the president of the home. Most recently, it has been used as a venue for special events.

In the murder room, a desk like the one Van Dorn sat at when a one-ounce piece of lead was fired into his brain stands against the far, back wall. In a gold frame, a large painting of the general hangs above a fireplace, on a robin egg-blue-painted wall.

“There’s a lot of me in this house,” says Wayman, who has filed for funding grants for the mansion and even painted walls of its many large rooms. There may be something of Van Dorn in the house, too. Splotches on the wood floorboards a foot or so from the commander’s replica desk appear to be blood. A sliver that was cut from the floor was tested in Nashville. The result: Confirmation of the presence of blood of an unknown male. Perhaps that’s only fitting. After all, “Van Dorn,” Bridget Smith says, “is quite the mystery.” ✯

John Banks is author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers, both by The History Press. He also is author of a popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). Banks lives in Nashville, Tenn.