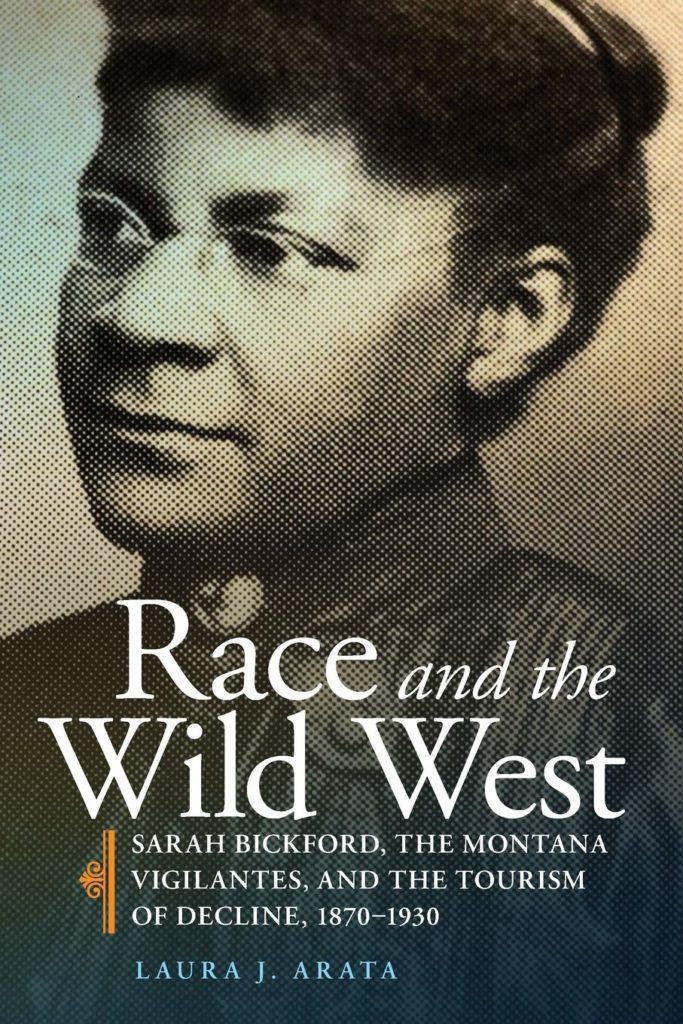

Race and the Wild West: Sarah Bickford, the Montana Vigilantes and the Tourism of Decline, 1870–1930, by Laura J. Arata, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2020, $24.95

When it comes to Montana Vigilantes, nothing is ever clear-cut. They have been both lionized and condemned for hanging (or “lynching”) road agent after road agent in such 1860s gold rush towns as Bannack and Virginia City. These executions (20 in January 1864 alone) had nothing to do with race, or very little (one early “innocent” victim was a Mexican, José Pizanthia); unlike the lynching going on in the South, no victim was black. Of course, Montana Territory had few resident black men and women then, and it’s still that way today (0.6 percent of the population). One Virginia City black woman, the fascinating Sarah Bickford, is the focus of this book, a Western Writers of America 2021 Spur Award finalist for best biography. One might think Bickford, who was born into slavery and arrived in Virginia City in January 1871, would have condemned the extralegal executions in the territory. Well, maybe she did (she never said so one way or another and was never physically present for these deadly events), but she came to run the city water company, and while headquartered in the Hangman’s Building she became an early proponent of vigilante tourism.

Perhaps the fact she was a shrewd businesswoman had something to do with her choosing for her headquarters the very site where on Jan. 14, 1864, vigilantes lynched five road agents, including “Clubfoot” George Lane, side by side from a central beam. Sarah kept the hangman’s beam exposed, preserving and promoting the space. One resident said Sarah “did not miss the opportunity to collect a few dimes from curious visitors wishing to see the hangman’s beam.” As to why Bickford (1852–1931) did it, author Laura Arata, an assistant professor of history at Oklahoma State University who specializes in the history of race and gender in the American West, offers this educated opinion: “In taking over the water company and a site of vigilante history, Sarah appropriated that legend as something of a shield, creating a unique niche for herself that enabled her to sidestep the pitfalls of refusing to occupy a standard social space while appropriating certain economic and social privileges not often available to black women.”

Of course, Sarah Bickford’s connection to the Montana vigilantes is only one aspect of her story. In the first two chapters Arata covers Sarah’s youth in Tennessee and her first marriage, to Irish immigrant John Brown (“If slavery had been its own kind of hell, being united in wedlock to John Brown was not much of an improvement”) and the loss of three children. Chapter 3 focuses on race in Virginia City and the West (including how the Chinese community was viewed), while Chapter 4 looks at Sarah’s second interracial marriage, to Stephen Eben Bickford, who died in 1900 and willed her and their three children his shares in the Virginia City Water Co. Chapters 5 and 6 detail her time running the water company, of which she became sole owner in 1917, making her the only black female public utilities owner in the nation.

The pioneering activities of 19th-century black residents of Montana and most everywhere else have received little coverage through the years. One exception in the “Treasure State” is Bickford’s contemporary Mary Fields (aka “Black Mary,” “Colored Mary,” “Stagecoach Mary,” etc.) a rough and tough hard-drinking, gun-carrying star-route mail carrier. Bickford was none of those things, yet she was a lot more—a brave black pioneer who, as the author suggests, defied convention in a white man’s world “in such a way that her femininity and respectability remained unimpeachable.” Her association with vigilante tourism in a town that was the capital of the territory when she got there but needed “Wild West history” to survive in the 20th century and beyond might be what draws readers to this book. But it was her association with the Virginia City Water Co. and the way she embodied racial pride and awareness (and instilled it in her children) that should most impress readers.

—Gregory Lalire

RACE AND THE WILD WEST

Sarah Bickford, the Montana Vigilantes and the Tourism of Decline, 1870–1930

By Laura J. Arata

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.