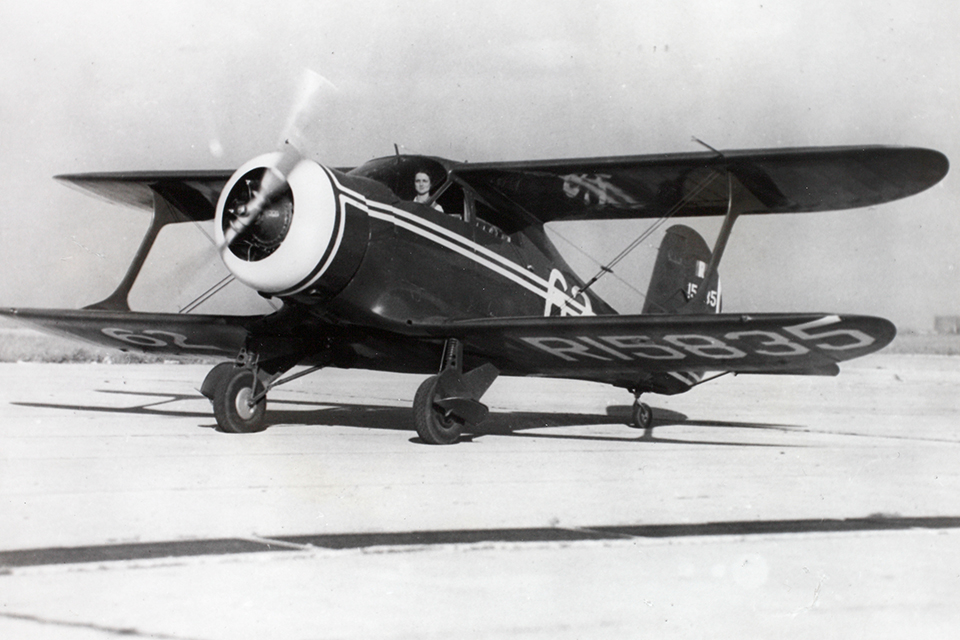

The beautiful Beech Staggerwing Model 17 embodies the handcrafted elegance of the golden age of civil aviation.

The Beech Staggerwing is just about everybody’s idea of the ultimate 1930s luxury private aircraft. There isn’t a 10-most-beautiful-airplanes list published that doesn’t include the Staggerwing, and every classic airplanes calendar devotes a photo to Beech’s backward bird. Yet this milestone biplane began life as a sales failure, and was ugly as a pug to boot. How it found its way to aviation-icon status is a tale that defines the growth and rapidly increasing sophistication of private flying in the 1930s and mid-1940s.

Walter Beech, who had joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I, followed the classic postwar path of barnstorming and itinerant flying, but he parlayed it into several increasingly important piloting and management jobs in the struggling Kansas aviation scene. In 1925 he and two other soon-to-be-famous names, Clyde Cessna and Lloyd Stearman, formed their own aircraft manufacturing company, Travel Air.

Travel Air pioneered the then-new concept of creating fuselage frames out of welded steel tubing rather than wood, and its open-cockpit biplanes were comparatively fast and reliable, thanks in large part to their Wright Whirlwind engines. The Model J Whirlwinds designed by Charles Lawrance were the world’s first dead-nuts dependable aircraft engines. They arrived after a decade of heavy, watercooled WWI survivors—Hispano-Suizas, Liberty V12s, dreadful Curtiss OX-5 V8s that were obsolete even before the war ended. The light, simple, bulletproof Wright family of radials, particularly the 9-cylinder J-5, made Charles Lindbergh’s Atlantic crossing not only possible but inevitable.

Travel Air’s most notorious product was its exclusive series of Type R Mystery Ships, though these were created despite Walter Beech. They were low-wing monoplanes, and Beech was a biplane guy. For him, the bridge truss created by a pair of strut- and wire-braced wings was the way to go, and this would be memorialized in his choice of a biplane configuration for the Staggerwing at a time when the industry was turning toward monoplanes.

The five Type Rs that Travel Air ultimately manufactured were a serious attempt to beat the military in the air racing game. Since the Army and Navy had exclusive access to powerful new engines, it was hard for civilian racers to best them. But the Mystery Ships—so called because they were created under plant-wide Travel Air secrecy—had several features that also found their way into the original Staggerwing: a thin, fast, Navy N-9 airfoil; a NACA full engine cowling; and slippery but pudgy wheelpants.

Walter Beech was a good pilot and an excellent businessman. Travel Air was sold to conglomerate Curtiss-Wright in 1929, and Beech suddenly found himself a rich man and a vice president, behind a desk in New York City. He didn’t enjoy it, because he had a dream of creating a personal superplane—an aircraft that would be the world’s fastest private airplane and an alternative to airline travel.

In October 1929, Wall Street augured in and Beech’s Curtiss-Wright stock plummeted from $30 a share to 75 cents, but Beech had squirreled away a nice cash horde from the sale of Travel Air. It was enough, in 1932, to bankroll the establishment of the Beech Aircraft Company, otherwise known as Beechcraft.

Herb Rawdon—the “R” in Mystery Ship Type R—had been Travel Air’s best-known name, but Walter chose to team up with a different Travel Air engineer, Princeton-educated Ted Wells, who became vice president and design chief of Beechcraft. Like Beech, Wells was a biplane guy. He was also an intuitive engineer, not a numbers man. This would serve him well in creating a slick, fast biplane, but it would also serve him poorly in getting the airplane certified by the Department of Commerce.

In an aviation equivalent of the Silicon Valley “born in a garage” meme, the Staggerwing was born in a kitchen, where Wells first sketched the basic layout. When he limned the original Staggerwing Model 17, it was not an attractive airplane. It had enormous though effective wheelpants over fixed, narrow-track landing gear. The wheels semi-retracted six inches into the wheelpants in flight, pulled up by electric motors against the coil springs/oleo struts. The engine was a broad, brutish 420-hp 9-cylinder Wright Cyclone on a snub nose. The airplane was overpriced, overpowered and faulty in several areas, with difficult landing characteristics and poor ground handling.

Ted Wells had learned to work with tube frames, fabric and wood. The era of monocoque metal airplanes that was just beginning was not his friend. Even in the mid-1930s, when he went on to design the Beech Model 18—the classic Twin Beech—he designed it around a massive tubular-steel-frame center section and cabin structure that extended outward to cantilever the twin radial engines. It has been said that the Staggerwing was the most complex single-engine airplane ever invented, making even World War II monocoque fighters look simple. As a result, every Staggerwing was slightly different—hand built, crafted, coaxed and teased into shape. Restoring a basket-case Stag is a job that has driven many a vintage-airplane pro to despair, if not bankruptcy.

It would be two years before the first Staggerwing was sold, for $14,565.81—equivalent to just over a quarter-million dollars today. It was the Beech Aircraft Company’s very first sale. Walter Beech’s timing had been unfortunate, for the Model 17 tried to find buyers during the worst years of the Depression. The Stag was a powerful, fast, expensive airplane intended for wealthy business executives, an increasingly rare breed.

Much of the problem was that it took forever to get the original 17 certificated for production. Ted Wells didn’t understand stress analysis, which was a new and increasingly important science in the early 1930s. The Model 17 was a far more powerful and more sophisticated airplane than the Department of Commerce inspectors were accustomed to approving, nor were they familiar with Wells and his capabilities. Worse, the inspectors kept finding mistakes in Wells’ stress-analysis computations. They also squawked a number of his design features, though it could be claimed that they were micromanaging every step of the approval process, in a manner familiar to anyone who has ever had to deal with cover-your-ass aviation bureaucrats.

The DoC’s reticence meant that Beechcraft had to continually produce new stress analyses, perform more tests and redesign components to the Feds’ liking. For a company that had yet to experience a single dollar of cash flow, this was a steadily growing problem.

Beech wasn’t shy about using big engines, and he had originally intended for the Model 17 to carry a new 710-hp Cyclone, which wasn’t certificated in time; the 450-hp version was a fallback. But once that first Model 17R was sold, Beech aggressively pursued the idea of a Super Stag utilizing the big Wright, now rated at 690 hp. It would be built as the Model A17F, with a top speed approaching 220 mph and a cruise of 200, which was always Walter Beech’s goal—close to fighter performance at the time, making it the ultimate 1930s biplane.

Beechcraft sold one A17F, in 1934, to Goodall Worsted, a maker of fancy fabrics and men’s suits. It took all of Walter Beech’s influence to get the A17F type-certificated, since Ted Wells continued to be casual about the necessary calculations, testing and paperwork.

Beechcraft carefully prepped a second A17FS (S for Special), this one with a 710-hp engine, for Louise Thaden to fly in the famous London-to-Melbourne MacRobertson International Trophy Race, which a de Havilland DH.88 Comet twin ultimately won. Wells did his best to turn the A17FS into a flying gas tank, but Beech ran out of money before the project was completed.

After sitting in a factory hangar for nine months, the airplane was bought by, of all people, the Bureau of Air Commerce, so that its test pilots could gain experience with this new generation of fast, powerful IFR airplanes. According to one BAC pilot, the A17FS was longitudinally unstable and difficult to fly. He also ran into near-disastrous wing and horizontal-tail flutter during a 260-mph dive. The BAC quickly sold the airplane back to Beechcraft and it eventually disappeared, assumedly disassembled for usable parts, the rest scrapped.

Meanwhile, the Staggerwing was evolving and improving. The B17 got fully retractable main landing gear and a wider stance, which helped both ground handling and the airplane’s looks. Walter Beech had also figured out that maybe gonzo engines weren’t the way to go—lots of extra weight, drag and expense for a minimal speed increase. The B17 was offered with 225- and 285-hp engine options, though the B17R was equipped with a 420-hp Wright R-975. Basic B models retailed for about $8,000, which was a third less than the original Stag’s $12,000-plus.

Engine choice made a huge difference in a Staggerwing’s selling price. The C17L with a 225-hp Jacobs radial went for $8,550, but the C17R, the same airplane with a 425-hp Wright, cost well more than twice that, at $18,300.

A note about the nomenclature: All Staggerwings were Model 17s. The initial letter—A, B, C and so on to the ultimate G—specified the seven substantial redesigns and upgradings. The final letter—B, E, L, R, S, etc.—was code for the manufacturer of each version’s engine, since there were at least 10 different engine/airframe combinations; some Staggerwing historians say 15, depending on how you count. The engine-ID letters bear no relationship to the engine manufacturer’s name, though certainly every serious Stag fan can decode the entire list.

Let’s also deal with the burning question, why negatively staggered wings? A conventional biplane has positively staggered wings, meaning the leading edge of the upper wing is forward of the lower wing’s leading edge. Negative stagger thus means an upper wing farther aft than the lower wing. Several rationalizations for Ted Wells’ design choice are typically offered—better stall characteristics and an ideal location for the main landing gear—but Wells actually had just one reason for choosing negative stagger: better cockpit visibility. The upper wing hid as little as possible of the pilot’s gaze upward and to the sides, and for Wells this was what made a cabin biplane workable: put the pilot out in the sunlight, not under a wing-roof.

The forward-mounted lower wing did allow the landing gear legs to be paired with the main wing spar rather than having to be braced and tied in separately to the fuselage framework. This made the adoption of retractable landing gear for all B- through G-model Staggerwings particularly easy, but that was an unintended consequence of Wells’ original design choice.

B17 Staggerwings had a comparatively short fuselage and an engine-heavy nose. With difficult-to-modulate Johnson bar brakes—a lever like the center-mounted parking brakes in many modern cars—the Bs still had lousy ground-handling characteristics. The Johnson bar applied both mainwheel brakes, and displacement of the rudder pedals determined how much braking power went to each wheel. It was an act of coordination that made keeping a Staggerwing straight on the rollout a challenge.

But the B hit a sweet spot—the right airplane at the right price at the right time—that attracted not only corporate operators but wealthy sport pilots. By September 1934, Beech had delivered 11 B17s, though all of them had temporary type certificates. Ted Wells still hadn’t been able to provide the Department of Commerce with the paperwork it needed to certify the airplane. The DoC blamed the delay on “the incompleteness, inaccuracy and generally unsuccessful completion of [Beech’s] technical data.” Still, a year later the sales total was 35 B17Es, Ls and Rs. The Staggerwing was on its way to worldwide fame.

The next Staggerwing model, the C17, found fame as the raceplane in which Louise Thaden and Blanche Noyes won the 1936 cross-country Bendix Trophy race. Thaden and Noyes flew a conservative race, knowing that to win, you have to finish. They stopped in Wichita, at the Beech factory, to refuel, and told Walter Beech that they were cruising at 65-percent power. He was furious. “What do you think you’re in,” he bellowed, “a potato race? Open this damn thing up!”

Thaden, knowing a bull male when she saw one, promised to two-block the throttle but went on to win the race at the same 65-percent power setting. When she later admitted this to Beech, he laughed and said, “That’s the best I ever heard. A woman winning the Bendix flying a stock airplane at cruise power.” Thaden got the Harmon Trophy for winning the race, and subsequently became a Staggerwing sales agent and demo pilot.

The all-metal Twin Beech 18 was Beech’s future, but Walter knew he needed to do something to upgrade the Stag and keep it in production. The result was the D17 and E17 series, with a lengthened fuselage for better landing and ground-handling characteristics, toe brakes in place of the old Johnson bar rig and a fully enclosed retractable tailwheel. The D17S, with a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial, became the most popular Staggerwing ever manufactured, and Beech now had a range of biplanes from the 166-mph-cruise E17L to the 202-mph D17S.

Unfortunately, trouble then struck: a series of accidents that blackened the famous biplane’s reputation. The first occurred in June 1938, when Baron Maximilian von Romberg, a wealthy heir to a famous German family, flew his E17B into bad weather near Red Bank, N.J. Von Romberg was neither instrument-rated nor -trained, and he fatally crashed. His nobility assured that the accident would be the subject of rumors—engine failure, structural problems—and this infuriated Walter Beech, who issued what would later be called a service bulletin, warning all Staggerwing pilots not to operate their airplane IFR. Compliance wasn’t mandatory, however, and six months later another Stag crashed in Louisiana, en route to Mardi Gras while IFR with a VFR-only pilot. All five aboard were burnt beyond recognition.

Worse was to come. In August 1939, an F17D came apart in flight while being flown by a Beech test pilot who had a reputation for doing violent aerobatics. He pulled the wings off at what was later deemed to be 15 Gs—certainly a bogus number, perhaps promulgated by Beech to suggest that Staggerwings were uniquely strong.

Beechcraft needed all the help it could get. During May and June 1940, three Staggerwing accidents were attributed to control-surface flutter. The problem had first surfaced during testing of the brute-force A17FS in 1935. Ted Wells thought he had fixed it with careful weighting of the aileron leading edges to counteract their tendency to find a free-floating point at which a particular airspeed could send them into an uncontrollable, buzzing flutter so severe that they would tear themselves from the wing or destroy the wing itself.

Beech could dispute the first alleged flutter-induced accident, since the evidence of flutter, if there indeed had been any, was destroyed in the ensuing fatal crash. But the next Staggerwing that experienced aileron flutter, in May 1940, survived with the evidence intact. Of the five people aboard that F17D, three were pilots, and one of them later testified that the airplane’s wings rapidly flapped up and down through an estimated five inches after the flutter began.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority was urged to ground the entire Staggerwing fleet, but it chose instead to limit Stag maximum speeds (160 mph tops, 140 in turbulence) and forbade their use in instrument flying. Two weeks later, the third crash occurred, in the Catskill Mountains of New York, and though the post-crash evidence wasn’t unequivocal, the wreckage strongly suggested an in-flight breakup. Whether this was caused by a VFR pilot flying into a thunderstorm, which was the case, or turbulence-inducing flutter, the airplane had been forced into an unsurvivable situation.

Beech would become familiar with this problem when the Staggerwing’s successor, the Beechcraft Bonanza, gained the cruel nickname “the doctor killer.” Both the Staggerwing and the Bonanza found their way into the hands of pilots wealthy enough to buy them but not smart enough to know their limits. The Stag survived despite calls for the grounding of the entire fleet.

Many Staggerwings ended up flying for the U.S. military during World War II. Initially, the Army Air Corps “requisitioned” some 120 privately owned Stags. The Army and Navy bought 270 slightly modified D17s and renamed them UC-43 Travelers. They were used as utility and liaison aircraft at various bases and at embassies in London, Paris and Rome.

The last Staggerwing built, a Model G17S, was delivered in June 1949, two years after the Bonanza had gone on sale. The Bonanza was vastly easier to manufacture than the Staggerwing, which was reflected in its price: just under $8,000 at a time when the Stag sold for $29,000.

The postwar G17S—sold only with a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney R-985—remains the ultimate Staggerwing, and is generally thought to be the most beautiful of all versions. It was identical to the popular D17S in power and performance, but sported a steeply raked windshield, full landing gear doors, and a longer and smoother cowling with cowl flaps. It had a top speed of 212 mph and cruised at 201 mph at 10,000 feet—to this day impressive performance for a normally aspirated general aviation single.

Staggerwing designer and Beech Vice President of Engineering Ted Wells outlasted his iconic airplane, but not by much. CEO Olive Ann Beech threw him overboard in 1953, giving him the choice of being fired or retiring. Wells chose the latter. He had become more interested in sailboats than airplanes, and had twice been the world champion racer of Snipes, one of the most intensely contested of all international one-design sailboat racing classes. Olive Ann—Walter Beech had married his secretary, who competently but imperiously took over the company after his death in 1950—felt that Wells was neglecting Beechcraft to go sailing.

In the 16 years from 1932 to 1948, Beechcraft manufactured 785 Staggerwings, the last several assembled from components bought back from a large Beech parts dealer. Two hundred and eighty-two airframes are thought to survive, but fewer than 100 are flying. Unlike rare classic cars, civil airplanes don’t attain stratospheric values, and a good, flying Stag can probably be had for half a million dollars. The Staggerwing’s reign as Queen of the Air was brief but spectacular.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: The Staggerwing Story, by Edward H. Phillips, and Staggerwing!, by Robert T. Smith and Thomas A. Lempicke.

This story was published in the May 2017 issue of Aviation History magazine. Subscribe here.