As Soviet ICBM tests and the launch of Sputnik in the 1950s added intensity to the Cold War, the United States turned its attention to the ice sheets of Greenland for an edge.

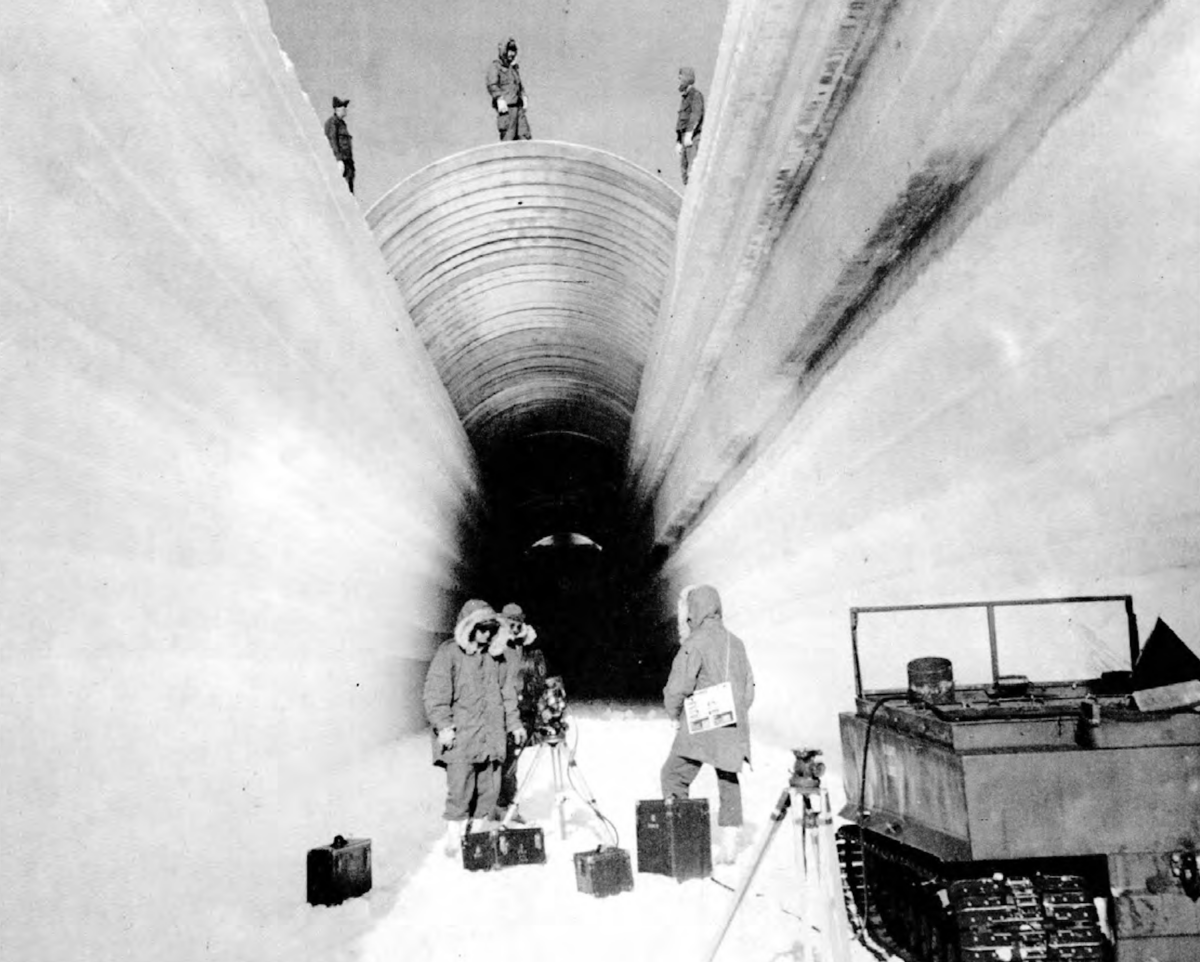

Meant to be a “city under the ice,” Camp Century was designed to be a series of “twenty-one horizontal tunnels spidering through the snow,” according to the University of Vermont. Designers boasted that, once complete, it would be three times the size of Denmark — replete with a movie theater, hot showers, a chapel, a library, chemistry labs, and, most importantly, a portable nuclear reactor.

Destined to house nearly 200 residents, the top-secret missile base in northwestern Greenland, far north of the Arctic Circle, was publicly touted as a “remote research community” under the auspices of the Army Polar Research and Development Center.

In reality, it was “a top-secret plan to convert part of the Arctic into a launchpad for nuclear missiles,” according to the Washington Post.

Dubbed “Project Iceworm,” the city nestled under layer after layer of ice was to be positioned less than 3,000 miles from Moscow. During the Cold War, the frigid location offered the U.S. Army a more covert and convenient cover for its medium-range ballistic missiles, or MRBMs.

The project was to take advantage of the strategic location of Greenland — midway between the two superpowers — so as to avoid using long-range Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, located stateside, professor Nikolaj Petersen of Denmark’s Aarhus University wrote in a 2007 article for the Scandinavian Journal of History.

In 1958, the U.S. received tacit approval from Denmark — which has maintained control of the world’s largest island since the 1814 Treaty of Kiel — after being approached with the plans for Iceworm by U.S. ambassador Val Petersen.

According to Petersen’s account, Danish Prime Minister H. C. Hansen replied, “You did not submit any concrete plan as to such possible storing, nor did you ask questions as to the attitude of the Danish Government to this item. I do no[t] think that your remarks give rise to any comments from my side.”

The U.S. deemed this a green light, with construction slated to begin in June 1959. Despite temperatures as low as -70°F, winds as high as 125 miles per hour and an annual snowfall of more than four feet, the audacious project was completed the following October, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation.

“The missile force is hidden and elusive,” a 1960 planning document noted. “It is deployed into an extensive cut‐and‐cover tunnel network in which men and missiles are protected from weather and, to a degree, from enemy attack. The deployment is invulnerable to all but massive attacks and even then most of the force can be launched. Concealment and variability of the deployment pattern are exploited to prevent the enemy from targeting the critical elements of the force.”

The audacious $2.71 billion plan didn’t account for one thing, however: Mother Nature.

It became increasingly clear, in short order, that building an atomic city under shifting ice sheets was tenuous at best. The project was scrapped entirely by 1967, and the massive underground structure collapsed shortly after.

Despite this rather large military gaffe, the project wasn’t entirely a waste. During the building of Camp Century, U.S. glacier scientist Chester Langway drilled “a 4,560-foot-deep vertical core down through the ice,” according to an account in the University of Vermont Today. “Each section of ice that came up was packaged and stored, frozen. When the drill finally hit dirt, the scientists worked it down for twelve more feet through mud and rock. Then they stopped.”

For decades, this layer of ice and rock from Greenland’s core remained untouched, stored in cookie jars at the bottom of a freezer in Denmark.Then in 2017, it was rediscovered by Jørgen Peder Steffensen, a professor and curator of the ice core repository at the University of Copenhagen, and glaciologist Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, who were going through the university’s extensive collections of ice cores in preparation for a move to a new freezer.

“Some were oddly labeled ‘Camp Century sub-ice,’” Steffensen told UVM Today. “I never thought about what was in those two boxes.

“Well, when you see a lot of cookie jars, you think: who the hell put this in here?” he continued. “No, I didn’t know what to make of it. But once we got it out, we picked it up to see these dirty lumps, and I said: what is this now? And all of a sudden it dawned on us: Oh s–t, this is the sediment underneath it. The ‘sub-ice’ is because it’s below the ice. Whoa.”

In October 2019 the overlooked bits of dirt finally had their time in the sun as more than 30 scientists from around the world gathered in Vermont to study what the silty ice and frozen sediment might tell us.

The convention discovered that the sediment contained “fossilized leaf and twig fragments, proving that plants had once grown under one of the coldest regions on earth,” according to the Washington Post story.

While the U.S. didn’t get to act out its Bond villain lair fantasies, it did, at the very least, further scientific understandings of the world around us — and below us.