More than just collectibles, the toy airplanes in your attic may reflect aviation history as well as your own youthful passions.

After our mom’s death, my sister and I spent some time preparing the “old homestead” for sale. Imagine my surprise when I discovered in a dark corner of the attic all of my old stuff—including lots of childhood treasures I thought had long since been consigned to the landfill. There were baseball cards, comic books and an old wooden box that my dad had made, containing a heap of my toys, many of which were aviation related. Most of the airplanes were smaller and more beat-up than I remembered them, but there they were.

The thing I remember most about the planes my friends and I had is that they didn’t last very long. Most couldn’t survive repeated test flights from second-story bedroom windows, or all those crash landings in dirt piles, after strafing the army men and dump trucks bunkered there. It never occurred to me as a 7-year-old that a diecast or tin airplane wasn’t really designed for such treatment. Maybe that’s why there seem to be fewer planes in antique shops compared to cars and trains.

Does that mean that the battered survivors are all valuable? Not necessarily. Collectors and dealers say that the value of such a toy depends on several variables, including how many were made, the complexity of the construction, the company that built it and of course the toy’s condition.

Just for fun, I decided to evaluate my own toys. I also contacted neighbors, friends and relatives to see what kind of impromptu collection I could put together. I managed to assemble a pretty good representative sampling of what are now known as collectibles.

A word of warning: The antiques shown on these pages are real toys. In other words, they’ve been played with. Most of us did not have the foresight to protect our toys in their original packaging, nor were they squirreled away in a safe-deposit box. They ended up in junk drawers, attic trunks and basement crates.

The dealers who set the standards for antique toy values use several methods that have evolved through the years. It used to be that a toy was simply labeled Good (G), Very Good (VG) or Mint (M) condition. Today most toy collectors have adopted a scale with a wider range, using a numerical designation:

C10 Mint, like new (higher price paid for Mint in original package)

C9 Near Mint, no noticeable flaws, tiny marks upon inspection

C8 Excellent, minor wear on edges only

C7 Very Fine, minor wear overall, very clean

C6 Fine, shows some wear in spots, but taken care of

C5 Good, wear evident overall, shows that it has been played with

With that in mind, I quickly realized that few toys I had collected would likely stand the scrutiny of even C5 standards. There are plenty of broken propellers, bent empennages and seized landing gear— not surprising in toys and games that have sat moldering in basements and attics for 30 years or so. But it certainly detracts from their monetary value. As one dealer explained, “Just being old doesn’t cut it.”

Several others told me that age, size or number produced may actually have less to do with value than what they call the nostalgia factor or desirability of a certain toy. Those concepts are more subjective, and can certainly be specific to a certain generation or region of the country. Other factors, such as how many parts were used in a toy’s construction, how accurate the details are and whether the toy was hand-finished, may also affect value.

For example, I grew up in Davenport, Iowa. In the 1920s a company across the Mississippi River in Illinois, Moline Pressed Steel, made the Buddy L line of toys, named for the son of company founder Fred Lundahl. Originally manufactured from leftover metal that was a byproduct of Lundahl’s fender-making business, the toys became so popular that the company started mass-producing them. Because of its local connections, people from the Midwest may be inclined to place a higher nostalgia value on Buddy L toys than on similar toys made elsewhere.

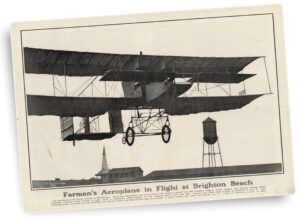

Of course, the earliest aviation toys were not mass-produced. They were formed from paper—for example, paper replicas of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machines—and other scrap materials. Countless fathers carved wooden airplanes and puzzles by hand from scrap lumber, and later milled the components on their basement Shopsmiths. Moms showed kids how to fold paper or cloth to make balloons, planes and parachutes.

Fisher-Price took the idea of wooden toys and made it into an empire. The firm mostly used ponderosa pine, painted in bright colors or covered in lithographed paper, decorated by company artists. Among the first artists who did this kind of work for the company was Margaret Evans Price, who cofounded the firm with her husband, Irving L. Price, in 1930. During World War II, Fisher-Price contributed to the war effort by manufacturing parts for real aircraft, such as ailerons for Allied gliders, as well as other components.

My collection includes one of my sister’s Fisher-Price pull-toy helicopters. When pulled along the floor, the wheels turn and then, thanks to a gear arrangement, the rotor also spins. In the 1960s, Fisher-Price turned to plastic for perennially popular toys like this. But many of the wooden lithographed versions can be quite valuable if in good condition. I’ve seen some with price tags of well over $100.

Cereal companies were the biggest manufacturers of mass-produced paper and cardboard aviation toys. Kellogg’s and Nabisco, for example, offered an extensive line of punch-out planes, some allegedly flyable, built right into the cereal box. In addition, box tops could be redeemed for more detailed fold-together planes and even airport hangars, along with aviation board games and puzzles.

During WWII, so-called Victory punch-outs of combat planes were extremely popular. If you happen to have one that’s in good condition, it could be quite valuable. Kellogg’s offered its PEP line of model warplane punch-outs, which it advertised as “authentic scale models suitable for silhouette identification.” All this was great for kids, but parents often lamented half-eaten boxes of cereal whose contents had to be stored elsewhere, because the boxes had been dismembered to feed a budding collector’s hunger for the latest warbird. As plastics technology advanced following the war, cardboard punch-outs gave way to small plastic planes that were packaged right inside with the cereal.

Cast iron was a very popular material for toys in the early 1900s, although its use peaked a bit too early in the 20th century for wide use in aviation models. What cast iron toys lacked in accurate detail they made up for in durability. They were heavy and tough—except for the propellers and wheels, generally made of lighter material, and often the first parts to disappear. Finding a genuine complete cast iron plane that was manufactured during the 1920s or ’30s is rare, and it can be worth hundreds.

Another process for producing durable early toys was the slush-cast method, where a molten antimony-lead mixture was poured into a mold, which was moved around to distribute the liquid, then poured out. These toys were hollow, so they weighed much less than cast iron toys. The Barclay Manufacturing Co., originally located on Barclay Street in Hoboken, N.J., made many different planes this way—which were later copied by a number of smaller, backroom toy makers, so watch out for fakes. One unusual aircraft set Barclay made was called a piggyback set: two separate planes, one smaller than the other, the larger plane having slots cut in its top to accept the landing gear of the smaller one. As years passed, most of these original sets became separated, and many missing pieces were replaced by mismatched toys, manufactured by Barclay (which existed until the early 1970s) or elsewhere. My own piggyback set is a hybrid, but it fits together well and shows how the toy worked.

Stamped steel toys became popular just before WWII and continued in production postwar. While many toy companies produced planes this way, Marx and Wyandotte were the largest competitors. I have a charming high-wing monoplane, its vertical stabilizer long gone, that could be from either of those companies, or might have been made by a smaller company in the 1930s. This is another style that is frequently copied by modern manufacturers.

Louis Marx and his brother David started their own toy company in 1919. Their skill at producing and selling durable, cheap toys made them a great success. My sturdy old Marx twin-engine cargo plane survived decades at the bottom of the heap in the toy chest. Throughout the Depression and until after WWII, Marx was the largest toy manufacturer in the world.

Marx’s primary competitor was All Metal Products Co., originally located in Wyandotte, Mich., so many of its toys were referred to as “Wyandottes.” All Metal got its start in the 1920s, and during WWII it produced materiel such as magazine clips for M-1 rifles. My own Wyandotte “Crusader,” a twin-boom, twin-engine fighter, was a very popular toy manufactured in several styles. Mine lost its slanted, leaf-shaped twin vertical stabilizers long ago, but the plane’s overall sturdy construction meant that it managed to survive many years of play.

Lots of homes in the early 1930s did not have wall-to-wall carpeting, and mothers complained that cast iron, slush-cast and stamped steel toys damaged their wood floors. The answer: rubber airplanes.

The biggest sales pitch was that since the toy was made almost entirely of rubber, it wouldn’t hurt wooden surfaces—and was also much quieter. Auburn Rubber Co. of Indiana and Sun Rubber Co. of Barberton, Ohio, were two of the largest producers of rubber planes and other transportation toys. Lead molds were used to form molten rubber. After trimming, the planes were dipped in vegetable dye, then usually handpainted and wrapped in waxed paper. Produced from about 1935 to 1955, they were cheap and very popular.

My collection has two rubber examples, one from Auburn and another from Sun. My Auburn pursuit plane, supposedly based on the Bell P-39 Airacobra, shows what can happen when a rubber toy gets too close to a furnace, or even after lengthy storage in a hot attic. But my Sun example, also a pursuit plane, is a $30 handpainted plane that my daughter discovered during one of our research trips to an antiques mall. She insisted that I buy it, saying, “Your other rubber airplane is so pathetic!”

During WWII as well as the Korean War, black ID planes were manufactured by several companies for military use as training aids for pilots, gunners and aircraft spotters. These could be hung from the ceiling, to aid with silhouette identification. The production information was marked on the planes’ bottoms in raised lettering (for example, British—Supermarine Spitfire—8-42). The date referred to the copyright or date of model manufacture rather than the real aircraft’s manufacture date.

Made from a variety of materials, including rubber, wood, plaster, cast iron and plastic, ID planes were created by Cruver, Leominster and Design Center, among others. While very few were sold to the public, most of them eventually reached private hands. Like the rubber toy planes, these were often susceptible to heat, and lots of them—like my own British de Havilland Mosquito—have twisted tail sections or bent wings. In good condition, they can now be worth over $100.

Probably today’s most widely collected aviation toys are die- cast models, originally produced as a byproduct of the process for making letters for linotype machines. Samuel Dowst developed a technique to make toy jewelry and doll furniture and later named his entire toy line after his daughter, Tootsie. Tootsietoy created many transportation toys, including my own die-cast North American Navion model, surprisingly intact after several decades of rattling around in a Dutch Masters cigar box. Most Tootsietoys are inexpensive when purchased individually, averaging from $5 to $30, but the value increases exponentially for boxed sets of two, five, 11 or more planes, especially if you find an original box that can be transformed into a hangar. The two Tootsietoy jet fighters in my collection are only a sample of a much larger “squadron” from the 1960s that was available with both hangar and airport buildings. Sometimes sets are worth thousands of dollars.

A Tootsietoy competitor was Midgetoy Co. of Rockford, Ill. Although its selection was not as large, the quality of its die casting was as good as if not better than others—according to a retired toy maker from Midgetoy. The Midgetoy samples in my collection date from about 1953, and he pointed out that they all have the telltale “sprag” (a sharp metal post) under the tail section, which resulted in many a gouged tabletop. In 1954 Midgetoy removed the sprags to make its toys more furniture friendly.

Another firm famous for die-cast planes was Hubley, founded in the late 1890s in Lancaster, Pa., by John Hubley, who used cast iron until the Depression, when the abundance of cheaper, lighter zinc alloy inspired him to make the switch. Hubley planes were popular, mainly because they were large and offered retractable landing gear and folding wings on some models. My collection includes three fairly well preserved Hubleys: a Curtiss P-40E, a Brewster F2A Buffalo (my personal favorite) and a model marketed as The American Eagle—but which I called my Republic P-47—with folding wings, retractable landing gear and, at one time, a clear plastic canopy. Those three are all I have left of a much larger Hubley squadron, including a Lockheed P-38, a Piper Cub and a Bell YFM-1 Airacuda, which I probably traded for baseball cards, comic books or bicycle parts. Hubley also got into plastics, including a version of the Buffalo that is not nearly as cool as my die-cast model.

Dinky Toy Co. in England is one of many foreign manufacturers that sold aviation toys in the United States starting in the 1930s. After WWII, which curtailed European toy making, Dinky started up again and produced even more (it remained in the toy business until the late 1980s). Its die-cast planes were similar in size to Tootsietoys but much heavier. The Avro York Airliner in my collection has seen better days—and lots of kid hours—since it was made in 1954. Dinky models range from about $40 to $150.

Matchbox Co. (aka Lesney Products), begun by Leslie and Rodney Smith in the mid-1950s, started selling its toys in America a few years later. By the time Universal Holdings bought out the Smith brothers in the mid-’80s, Matchbox had become one of the world’s most popular lines of transportation toys. My own collection includes a very combat-weary Vought F4U Corsair, rescued after many years from behind the old homestead’s woodpile, where it very likely crash-landed after a second-floor launching in Pappy Boyington fashion. What is this scarred, weathered toy worth to a collector? Maybe two bucks. But I wouldn’t part with it for $200 (well—maybe).

Bachmann Brothers in Philadelphia, which competed with Matchbox for a share of the small-boxed-toy market, later merged with Lintoy and mass-produced the Mini-Planes line of metal planes from the 1960s to the 1980s. Bachmann also made a line of plastic planes that had good detail but were not as durable, intended for collecting rather than play.

Although tin toy planes have been around since early in the 20th century, most of the popular models were imported from Japan in the 1950s. Their quality varied widely. Some incorporated friction drives, or wind-up units that could propel the plane across the floor. Others were battery powered and had twirling props, flashing lights or even early remote-control units. My collection includes what’s called a “Scorpion Jet,” similar to a Grumman F9F-5 carrier-based jet fighter, with folding wings that still work but a friction drive landing gear that has long since lost its spunk. In working order, these toys can be valuable—worth up to hundreds of dollars.

Want to know more about the toys in your attic? You can turn to a variety of reference books and Web sites, but also try to talk with dealers and collectors, who can often explain the finer points of a toy’s history. Remember, however, that you’re the only one who can understand its nostalgia factor.

I saw some very impressive toy planes in the course of my research, some of which looked like they had just come off the workbench. But as I look at the planes in my own “sub C-5 collection,” I don’t really mind that my toys aren’t worth very much money. For me, they’re toys, not collectibles. It’s their imperfections that make my own planes unique. So they’re priceless to me.

Educator and freelance writer Scott M. Fisher writes from Allerton, Iowa. For additional reading, try: Collecting Toy Airplanes: An Identification and Value Guide, by Ron Smith; Diecast Toy Aircraft: An International Guide, by Sue Richardson; and Collecting Toys: A Collector’s Identification and Value Guide, by Richard O’Brien.

Originally published in the September 2006 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.