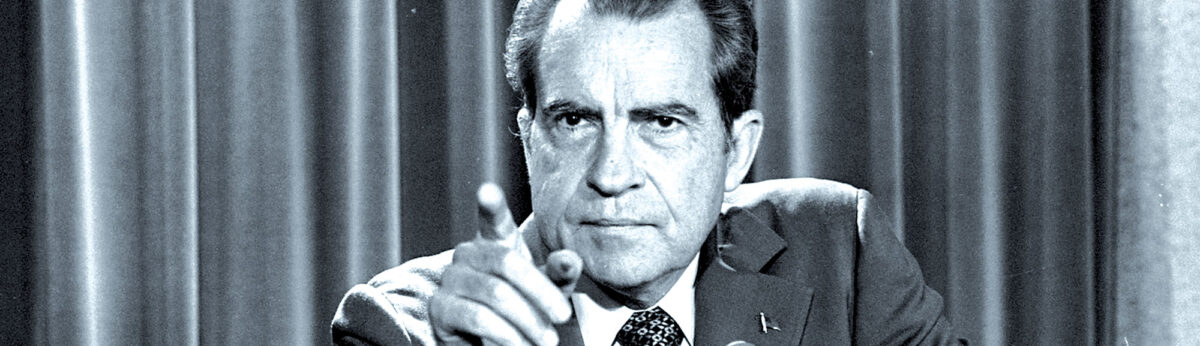

By August 1, 1974, the Watergate scandal was consuming Richard M. Nixon’s presidency. The House Judiciary Committee had filed three articles of impeachment naming the beleaguered chief executive. The president was seeing support for him erode even among Republican stalwarts, and with each sweltering Washington day, his departure from office seemed more likely.

Removal, however, was the lesser of Nixon’s problems. The first article of impeachment charged him with obstruction of justice, not only an impeachable offense but a federal crime. The 37th president was facing the prospect of becoming the first American chief executive to be removed from office and the first to be indicted and hauled into criminal court.

Nixon’s last chance for a semblance of relief was an often-overlooked, sometimes misunderstood presidential power: the pardon. Even if it could not keep him in the Oval Office, a pardon could keep him from being prosecuted. The question was, should Nixon try to pardon himself, or should he trust Vice President Gerald R. Ford, upon succeeding him, to pardon him?

The pardon rightly has been called the most imperial of American presidential perquisites. The power belongs to the president alone. Congress cannot limit the pardon authority, and the courts cannot review exercises of the pardon power.

The gesture often, but not always, comes as a president’s term is running out. The only presidents not to exercise their power to pardon were William Henry Harrison and James Garfield, both dead soon after taking office.

Andrew Johnson issued the largest number of pardons: amnesties for thousands of former Confederates. George H.W. Bush issued the fewest: 77.

Presidents have pardoned not only traitors—Iva “Tokyo Rose” D’Aquino, a World War II Japanese radio propagandist, got a pardon from Ford—but the dead. Bill Clinton pardoned Henry O. Flipper, West Point’s first African-American graduate, for a 117-year-old court-martial conviction.

Chief executives have pardoned those they did not know as well as they thought—Ronald Reagan pardoned ex-FBI official W. Mark Felt for Vietnam-era invasions of leftists’ residences long before it emerged that Felt had been the “Deep Throat” guiding Watergate reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—and those they could not have known better. Clinton pardoned his own brother, Roger, convicted years before of federal drug offenses. On occasion, pardons have stirred bitter controversy. Clinton’s 2001 pardon of politically connected commodities broker Marc Rich, who had fled the country to avoid a tax-evasion prosecution, brought howls of complaint.

So did George W. Bush’s 2007 commutation of the prison sentence of I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby Jr., a former vice-presidential chief of staff convicted of lying to FBI agents and a grand jury. Barack Obama’s 2017 commutation of most of the remaining prison term of Chelsea Manning, an army intelligence analyst who had supplied Wikileaks with classified documents, also elicited yawps.

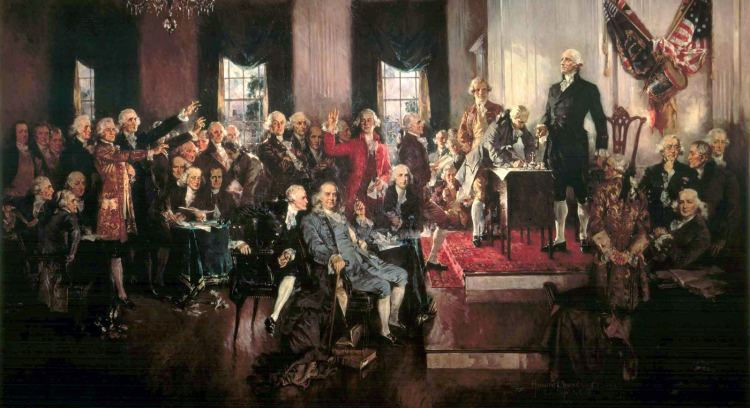

The pardon power, among the most intriguing aspects of the executive branch, dates to the Republic’s infancy. Delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention wanted to establish an office of chief executive strong enough to allow holders to do the job but not so strong as to foster an atmosphere—or reality—of dictatorship. The conveners assumed that, like England’s monarch, America’s chief executive should have the power to pardon individuals accused or convicted of crimes. Savvy judges of human character and human frailty, the delegates recognized the pardon’s explosive nature. Used properly, a pardon could confer mercy and enhance the public weal with a gesture of goodwill. Misused, a presidential pardon might put a party deserving punishment beyond the law’s reach.

Debating the issue, Virginia delegate Edmund Randolph, a staunch federalist, voiced fear that, by pardoning iniquitous accomplices, a traitorous president could shield himself from justice. “The President may himself be guilty,” Randolph said. “The Traytors may be his own instruments.” Fellow Virginian and fervent anti-federalist George Mason agreed. Mason imagined the pardon power being “sometimes exercised to screen from punishment those whom he [the President] has secretly instigated to commit the crime, and thereby prevent a discovery of his own guilt.”

A majority of convention delegates concluded that the specter of impeachment would deter a president from doing wrong or exercising the pardon power on his own behalf. “If he be himself a party to the guilt, he can be impeached and prosecuted,” said federalist delegate James Wilson of Pennsylvania, who in 1789 would be a charter member of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Constitution assigned the chief executive full authority “to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” The rationale, Alexander Hamilton wrote, was that “without an easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel.”

As states were ratifying the Constitution, James Iredell, an influential North Carolina lawyer also to serve on the first high court, said he saw no need to encourage subordinates to turn on a president. Beware the accomplice who seeks a pardon, Iredell warned.

“He would be a witness with a rope about his own neck, struggling to get clear of it at all events,” the North Carolinian said. “Would any men of understanding, or at least ought they, to credit an accusation from a person under such circumstances?” The Constitution does permit a president to pardon accomplices, although nothing suggests that the delegates envisioned a chief executive with the effrontery to try to pardon the person in the mirror.

The pardon power is broad but not limitless. In addition to the proscription on their use in instances of impeachment, presidential pardons cannot apply to even the most trivial violation of state or local law—they cover only federal offenses, criminal and military. A pardon can preempt criminal prosecution of a person not yet charged or convicted, but crimes must have been committed; a pardon cannot immunize an individual against prosecution for future crimes. In issuing a pardon, a president can limit the benison’s impact to reducing a prison term, also known as commutation, leaving intact other consequences of conviction. For every full pardon he granted, Obama commuted eight other felons’ federal sentences. A pardon does not erase a federal conviction, but does restore to the recipient rights the conviction took away, such as voting, serving on juries, and holding public office. Presidents can issue posthumous pardons (see “Pardoning Lieutenant Flipper,” side bar below).

George Washington issued the first presidential pardon, on July 10, 1795, to two leaders of the Whiskey Rebellion, an anti-tax insurrection. Washington said he acted because one was a “simpleton” and the other “insane.” During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln granted 343 pardons, many to Union Army deserters facing execution. “If Almighty God gives a man a cowardly pair of legs,” the president said, “how can he help their running away with him?” When generals complained that mercy was undermining discipline, Lincoln instead stayed executions pending his further orders. “If your son never looks on death till further orders come from me to shoot him,” he told a deserter’s father, “he will live to be a great deal older than Methuselah.”

The Confederacy’s capitulation brought the pardon power to the fore. Some northerners wanted former Confederates imprisoned, even exiled, impracticable sanctions given the hundreds of thousands of men involved and also a gesture whose inherent vindictiveness would hamper efforts to bind up the nation’s wounds. On May 29, 1865, in a wholesale act, Johnson pardoned all former military personnel below the rank of colonel in the Confederate Army or lieutenant in its navy. Johnson stipulated that higher-ranking former Confederate military officers and West Point or Annapolis graduates who had turned their coats had to apply individually for pardons, along with all civil and diplomatic officers of the “pretended Confederate government.” Pardons applied for, Johnson vowed, would “be liberally extended as may be consistent with the facts of the case and the peace and dignity of the United States.”

Among the first former Confederates to apply for a pardon and swear an oath of allegiance to the United States was General Robert E. Lee, on June 13, 1865. “True patriotism sometimes requires of men to act exactly contrary, at one period, to that which it does at another,” Lee told fellow Confederate veteran P.G.T. Beauregard in an October 1865 letter. “And the motive which impels them—the desire to do right—is exactly the same.”

Given Lee’s “deified position” among southerners, The New York Times said, his application stood as “a hopeful sign.” Johnson let Lee’s application languish, perhaps fearing a backlash among northerners avid for retribution. Lee’s day would not come until 1975, when President Ford signed not a pardon but a joint congressional resolution symbolically restoring Lee’s “full rights of citizenship,” something possibly accomplished by an 1898 statute.

Ire over pardons was not all Unionist. “`Tis been said that I should apply to the United States for a pardon,” said former Confederate President Jefferson Davis. “But repentance must precede the right of pardon, and I have not repented.” A postwar song popular in the defeated region proclaimed:

Oh, I’m a good old Rebel,

Now that’s just what I am.

For this “fair land of Freedom”

I do not care a damn.

I’m glad I fought against them;

I only wish we’d won,

And I don’t want no pardon

For anything I’ve done.

Johnson paid a price for conciliation. In 1868, the House of Representatives impeached him and the Senate came within one vote of removing him from office. The charges centered on the Tenure of Office Act, not presidential pardons. However, Johnson’s amnesty for ex-Confederates played a part, alienating vengeful Radical Republican leaders. For spurning their bloody-mindedness toward the South, they spearheaded impeachment efforts against Johnson.

On December 25, 1868, still holding the office from which he would be retiring in a few months, Johnson again exercised his pardon power, this time more broadly. He issued a blanket amnesty unilaterally pardoning “every person who, directly or indirectly, participated in the late insurrection or rebellion.” This document, which Johnson hoped would “renew and fully restore confidence and fraternal feeling among the whole people,” covered Lee, whose formal pardon application would never be acted on, and the obdurate Davis, who still was refusing to seek a formal pardon. The Christmas Day pardons were self-executing; no application or acceptance was needed.

Some presidential pardons poke sharply at would-be recipients. On December 31, 1913, New York Tribune city editor George Burdick and William L. Curtin, the paper’s shipping news editor, reported that the U.S. Customs Service was pursuing a political high roller. The charge was avoiding duties on jewelry the fellow had smuggled into the United States from Europe. The Tribune could have snagged this scoop only from someone at the Customs Service. Suggesting that the paper had bribed its way to inside information, the Justice Department demanded to know the journalists’ source. Subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury, Burdick and Curtin lawfully invoked the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

A month later, prosecutors again subpoenaed the pair, adding a high-pressure twist. On February 14, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson had granted Burdick and Curtin full pardons for any crime pertaining to their story, a ploy to muscle the newsmen into talking. The pardon eliminated criminal liability, erasing Fifth Amendment protections. The newsmen rejected the pardons. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. On January 25, 1915, the justices unanimously held that Burdick and Curtin were within their rights to refuse Wilson’s proffer, rendering the pardons void. The editors had this choice, the court reasoned, because acceptance of a pardon “carries an imputation of guilt.”

Pardons can be intensely political. During World War I, a federal court sent socialist leader and anti-draft activist Eugene V. Debs, convicted of sedition, to prison for 10 years. Wilson vowed never to pardon Debs. But in 1920, running for president from behind bars against Wilson’s designated Democratic heir, James M. Cox, and Republican Warren G. Harding, Debs got nearly a million votes, helping to ensure Harding’s victory. On December 23, 1921, President Harding commuted Debs’s sentence.

For the next half century, the pardon power, while regularly exercised, lay dormant in the public imagination. In 1974, however, as Richard Nixon toyed with the daring notion of issuing himself a blanket pardon for Watergate-related crimes, the spotlight again fixed on the imperial prerogative. White House Counsel J. Fred Buzhardt told Nixon he thought his boss had the constitutional authority to pardon himself; however, the Justice Department disagreed. Musings about the self-pardoning scenario prompted legal scholars, pundits, and armchair historians to begin a debate, still ongoing, as to whether a president can pardon himself and to wonder what sequences of events so brazen a move would trigger. Not willing to find out, Nixon implored Gerald Ford for a guarantee that upon taking office he would pardon Nixon. Ford refused. Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974.

Within a month, seeking closure on what upon taking office he had called “our long national nightmare,” Ford seized on Burdick and the imputation of guilt implicit in accepting a pardon, which made pardoning Nixon palatable. On September 8, 1974, Ford granted his predecessor “a full, free, and absolute pardon” for any crimes Nixon committed as president. Nixon accepted the pardon, publicly expressing “regret and pain at the anguish my mistakes over Watergate have caused the nation and the Presidency”—and, in Ford’s and many other Americans’ eyes, tacitly admitting guilt. To his last day, Gerald Ford kept in his wallet an excerpt from Burdick, ready should anyone accuse him of having let Nixon off with no acknowledgement of guilt.

Pardoning Lieutenant Flipper

The young officer had a final chance to save his U.S. Army career. Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper, 25, had been found guilty in December 1881 of “conduct unbecoming an officer.” The mandatory penalty was dismissal from the service. Flipper, West Point’s first African-American graduate, hoped that President Chester A. Arthur would pardon him. Flipper did get his pardon—but not until more than a century later.

Flipper, born a slave in Thomasville, Georgia, in 1856, aspired to an army career after Emancipation. That the U.S. Military Academy had never graduated an African-American did not deter him. In January 1873, Flipper wrote to newly elected Representative James C. Freeman (R-Georgia) seeking an appointment to the academy. “As you were the first applicant, I am disposed to give you the first chance,” Freeman responded.

Flipper passed the entrance exams and that May arrived at West Point. Fellow cadets initially accepted him, but circumstances changed. “In less than a month,” Flipper later wrote, “they learned to call me ‘n——’ and ceased altogether to visit me.” In June 1877, Flipper graduated 50th in a class of 76, West Point’s first black graduate and the Army’s only black officer. The new second lieutenant was assigned to the all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment, known as the Buffalo Soldiers (“Rough Ride,” February 2018). In 1878, he published The Colored Cadet at West Point, an autobiography a reviewer said showed “that pluck, manliness, and perseverance can elevate any one from a humbler sphere to a higher one.”

In 1880, the Army assigned Flipper to Fort Davis, Texas, where he was appointed commissary officer. Equivalent to civilian dry-goods stores, commissaries served not only a post’s garrison but civilians working at the post and living nearby. Transactions at the Fort Davis commissary amounted to hundreds of dollars a month, and each month Flipper and fellow commissary officers across Texas reconciled their books, sending reports and cash to Major Michael P. Small, chief Army commissary officer for Texas.

At Fort Davis, Flipper made few friends among fellow officers, whom he derisively labeled “hyenas.” Army officers had servants; Flipper’s was an African-American civilian named Lucy Smith. In March 1881, Colonel William R. Shafter, 45, took command of Fort Davis, and his reputation as a tough boss preceded him. Many subordinates found him coarse, gruff, and demanding.

In April, commissary chief Small alerted subordinates statewide that he would be away during May and June, instructing them to hold their reports and deposits until he returned. Flipper let his recordkeeping slide, storing records and cash in his personal trunk, not in the commissary safe. In early July, Small ordered Texas Department commissary officers to send their accounts and receipts for May and June.

Checking his books, Flipper discovered he was several thousand dollars short. Many soldiers owing the commissary money were in the field; Flipper expected that they would pay up and that he could make good any remaining difference with his own funds. Still, he was uneasy. He had been warned that Shafter “would improve any opportunity to get me into trouble.”

Stalling, Flipper naively adjusted his commissary books to make the accounts appear to balance. Shafter ordered him to send Small the requested report and funds. Expecting Small to see through his manipulations, Flipper submitted nothing, but three times assured Shafter that he had sent the report and $3,791.77, including his own check for $1,440.43, written on the expectation of royalty payments from his publisher. In early August, Shafter realized Flipper had been lying. A search of the lieutenant’s quarters turned up $400 in loose cash, some in Flipper’s personal trunk, to which Smith apparently had access because searchers found her clothing in it. As soldiers were escorting Smith from the fort, Shafter’s orderly saw her trying to conceal something; she was hiding in her bosom $2,853.56 in checks made out to the commissary. The purloined checks included several Flipper had claimed to have forwarded to Small and the check Flipper had written to balance the account. Flipper’s bank told Shafter the check would have bounced.

Shafter had Flipper arrested, confiscated his academy ring, and confined him to a cramped, blisteringly hot cell. The arrest drew immediate attention. The Texas Department commander ordered Flipper released. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln directed that Flipper “must have the same treatment as though he were white.”

As commissary officer, Flipper had done business with local merchants, and had treated them fairly. These civilians rallied to Flipper, collecting donations to square the young lieutenant’s accounts. “From his intelligence and good behavior, I liked the man and tried to help him if I could,” said merchant J.B. Shields, who donated $50. In a time of need the previous spring, Flipper had given Shields food for his family from his own personal larder. Within a week, Shields and other civilians had raised—and Shafter had accepted—$2,074, enough to make the government whole. But Shafter still charged Flipper with embezzling the money Flipper claimed to have sent Small, and with conduct unbecoming an officer for lying and issuing a bum check. Under Army regulations, a conviction for conduct unbecoming required dismissal from the Army. The missing money’s trail remains a mystery, perhaps known only to Smith, whose fate is similarly unknown.

Flipper’s case became a cause celebré. Having a “peculiar responsibility as a representative of his race,” The New York Times wrote, Flipper should have taken more care. The Globe, an African-American newspaper, lamented that even the defendant’s “best friends must criminate him of carelessness and looseness in keeping his accounts and cash funds.”

On November 1, 1881, Flipper appeared before an 11-officer court martial panel. The Army’s embezzlement case collapsed quickly. Flipper denied stealing, and Shafter had no proof that his commissary officer had done so. Flipper declared “in the most solemn and impressive manner possible that I am perfectly innocent in every manner, shape or form.” The conduct unbecoming charge was more problematic because Flipper had lied to Shafter. Defense counsel Captain Merritt Barber argued that white colleagues’ ostracism at West Point and at Fort Davis had taken its toll: “Is it strange that when he found himself in difficulties which he could not master, and confronted with a mystery he could not solve, he should hide it in his own breast and endeavor to work out the problem alone as he had been compelled to do all the other problems of his life?”

On December 8, 1881, the panel cleared Flipper of theft but convicted him of conduct unbecoming, dooming him to dismissal from the service. However, Army regulations required the president to confirm any officer’s dismissal, and the president also had the constitutional power to pardon a soldier in Flipper’s situation. In similar cases, white officers had been allowed to stay in the Army. In Washington, DC, Judge Advocate General David G. Swaim was aghast at Flipper’s treatment. Swaim knew of no instance, he wrote to Lincoln, “in which an officer was treated with such personal harshness and indignity upon the causes and grounds set forth as was Lieut. Flipper by Col. Shafter.” Swaim recommended Flipper be allowed to remain in uniform.

The “general impression in well informed circles,” the Army and Navy Journal reported, was that President Arthur would reduce Flipper’s penalty. The New York Times characterized Arthur as “disposed to grant the mitigation recommended by the Judge-Advocate-General.” However, on June 14, 1882, without comment, the president confirmed Flipper’s dismissal.

In later decades, Flipper lived in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, working as a surveyor and mining engineer and becoming an expert on Spanish land grants. Historian Charles M. Robinson III calls him “one of the great behind-the-scenes players in the development of the Southwest.” In 1914 and again in 1916, newspapers sensationally but falsely reported Flipper to be the brains behind Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa’s campaign. Flipper died in Georgia in 1940. On February 19, 1999, responding to descendants’ requests, President Bill Clinton granted Henry Ossian Flipper a presidential pardon. “This good man has now completely recovered his good name,” Clinton said.