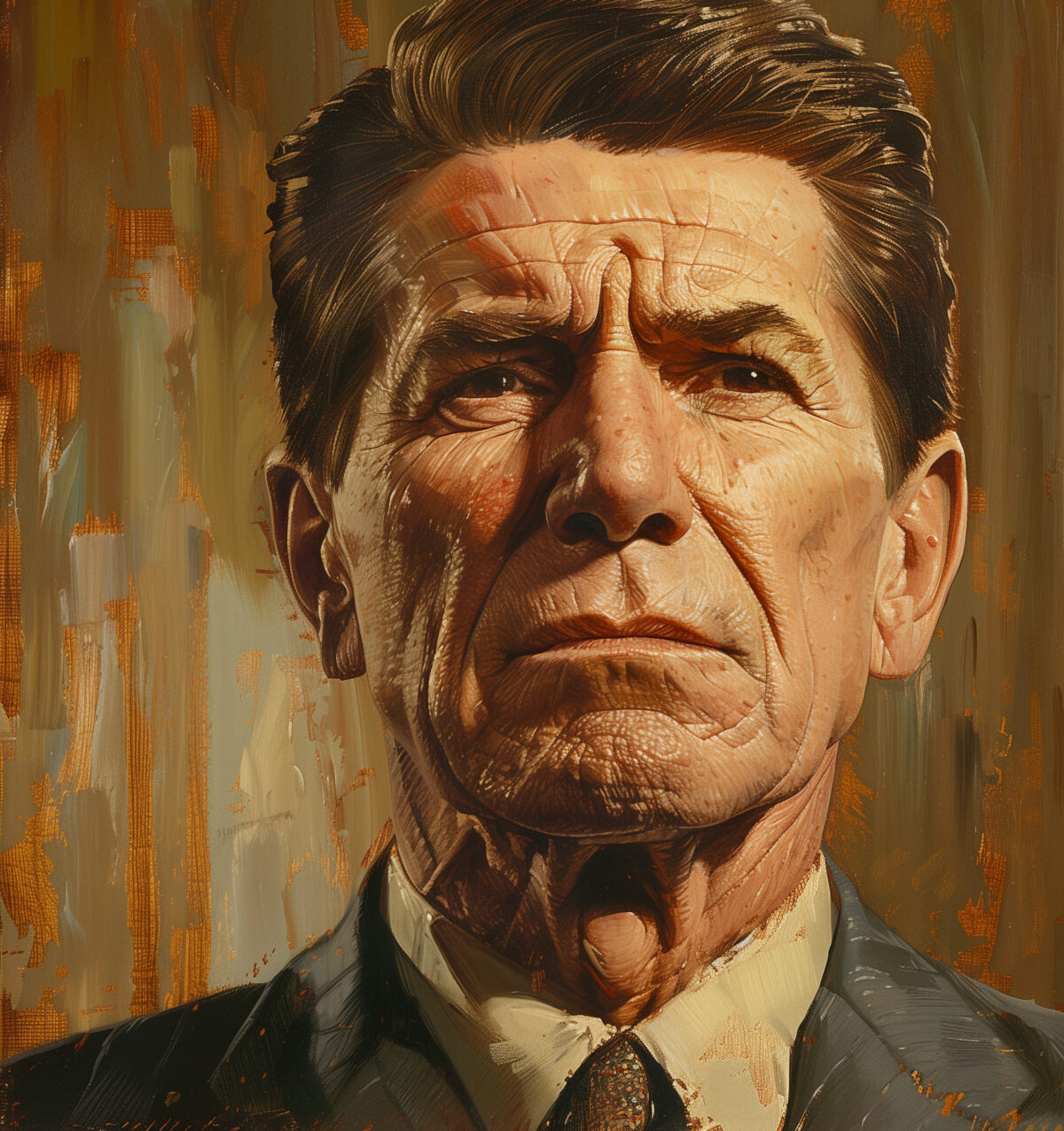

Twenty years ago, Ronald Reagan ordered American troops to invade Grenada and liberate the island from its ruling Marxist dictator. By itself this would have been an insignificant military action: Grenada is a tiny island of little geopolitical significance. But in reality the liberation of Grenada was a historic event, because it signaled the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine and inaugurated a sequence of events that brought down the Soviet empire itself.

The Brezhnev Doctrine stated simply that once a country went Communist, it would stay Communist. In other words, the Soviet empire would continue to advance and gain territory, but it would never lose any to the capitalist West. In 1980, when Reagan was elected president, the Brezhnev Doctrine was a frightening reality. Between 1974 and 1980, while the United States wallowed in post-Vietnam angst, 10 countries had fallen into the Soviet orbit: South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, South Yemen, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Grenada and Afghanistan. Never had the Soviets lost an inch of real estate to the West.

The liberation of Grenada changed that. For the first time, a Communist country had ceased to be Communist. Surely the Politburo in Moscow took notice of that. The Soviet leadership, we now know from later accounts, also noted that in Ronald Reagan the Americans had elected a new kind of president, one who had resolved not merely to ‘contain’ but actually to ‘roll back’ the Soviet empire.

Containment. Rollback. These sound like words from a very different era, and in a sense they are. With the sudden and spectacular collapse of the Soviet Union, we find ourselves in a new world. But how we got from there to here is still poorly understood. Oddly there is very little debate, even among historians, about how the Soviet empire collapsed so suddenly and unexpectedly. One reason for this, perhaps, is that many of the experts were embarrassingly wrong in their analysis and predictions about the future of the Soviet empire.

It is important to note that the doves or appeasers (the forerunners of today’s antiwar movement) were wrong on every point. They showed a very poor understanding of the nature of communism. For example, when Reagan in 1983 called the Soviet Union an ‘evil empire,’ columnist Anthony Lewis of The New York Times became so indignant at Reagan’s formulation that he searched through his repertoire for the appropriate adjective:’simplistic,”sectarian,’ ‘dangerous,’ ‘outrageous.’ Finally Lewis settled on ‘primitive…the only word for it.’

Writing during the mid-1980s, Strobe Talbott, then a journalist at Time and later an official in the Clinton State Department, faulted officials in the Reagan administration for espousing ‘the early fifties goal of rolling back Soviet domination of Eastern Europe,’ an objective he considered unrealistic and dangerous. ‘Reagan is counting on American technological and economic predominance to prevail in the end,’ Talbott scoffed, adding that if the Soviet economy was in a crisis of any kind ‘it is a permanent, institutionalized crisis with which the U.S.S.R. has learned to live.’

Historian Barbara Tuchman argued that instead of employing a policy of confrontation, the West should ingratiate itself with the Soviet Union by pursuing ‘the stuffed-goose option — that is, providing them with all the grain and consumer goods they need.’ If Reagan had taken this advice when it was offered in 1982, the Soviet empire would probably still be around today.

The hawks or anti-Communists had a much better understanding of totalitarianism, and understood the necessity of an arms buildup to deter Soviet aggression. But they too were decidedly mistaken in their belief that Soviet communism was a permanent and virtually indestructible adversary. This Spenglerian gloom is conveyed by Whittaker Chambers’ famous remark to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1948 that in abandoning communism he was ‘leaving the winning side for the losing side.’

The hawks were also mistaken about what steps were needed in the final stage to bring about the dismantling of the Soviet empire. During Reagan’s second term, when he supported Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform efforts and pursued arms reduction agreements with him, many conservatives denounced his apparent change of heart. William F. Buckley urged Reagan to reconsider his positive assessment of the Gorbachev regime: ‘To greet it as if it were no longer evil is on the order of changing our entire position toward Adolf Hitler.’ George Will mourned that ‘Reagan has accelerated the moral disarmament of the West by elevating wishful thinking to the status of political philosophy.’

No one, and least of all an intellectual, likes to be proved wrong. Consequently there has been in the past decade a determined effort to rewrite the history of the Cold War. This revisionist view has now entered the textbooks, and is being pressed on a new generation that did not live through the Soviet collapse. There is no mystery about the end of the Soviet Union, the revisionists say, explaining that it suffered from chronic economic problems and collapsed of its own weight.

This argument is not persuasive. True, the Soviet Union during the 1980s suffered from debilitating economic problems. But these were hardly new: The Soviet regime had endured economic strains for decades, on account of its unworkable Socialist system. Moreover, why would economic woes in themselves bring about the end of the political regime? Historically, it is common for nations to experience poor economic performance, but never have food shortages or technological backwardness caused the destruction of a large empire. The Roman and Ottoman empires survived internal stresses for centuries before they were destroyed from the outside through military conflict.

Another dubious claim is that Mikhail Gorbachev was the designer and architect of the Soviet Union’s collapse. Gorbachev was undoubtedly a reformer and a new kind of Soviet leader, but he did not wish to lead the party, and the regime, over the precipice. In his 1987 book Perestroika, Gorbachev presented himself as the preserver, not the destroyer, of socialism. Consequently, when the Soviet Union collapsed, no one was more surprised than Gorbachev.

The man who got things right from the start was, at first glance, an unlikely statesman. He became the leader of the Free World with no experience in foreign policy. Some people thought he was a dangerous warmonger; others considered him a nice fellow but a bit of a bungler. Nevertheless, this California lightweight turned out to have as deep an understanding of communism as Alexander Solzhenitsyn. This rank amateur developed a complex, often counterintuitive strategy for dealing with the Soviet Union, which hardly anyone on his staff fully endorsed or even understood. Through a combination of vision, tenacity, patience and improvisational skill, he produced what Henry Kissinger termed ‘the most stunning diplomatic feat of the modern era.’ Or as Margaret Thatcher put it, ‘Reagan won the cold war without firing a shot.’

Reagan had a much more sophisticated understanding of communism than either the hawks or the doves. In 1981 he told an audience at the University of Notre Dame: ‘The West won’t contain communism. It will transcend communism. It will dismiss it as some bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.’ The next year, speaking to the British House of Commons, Reagan predicted that if the Western alliance remained strong it would produce a ‘march of freedom and democracy which will leave Marxism-Leninism on the ash heap of history.’

These prophetic assertions—dismissed as wishful rhetoric at the time—raise the question: How did Reagan know that Soviet communism faced impending collapse when the most perceptive minds of his time had no inkling of what was to come? To answer this question, the best approach is to begin with Reagan’s jokes, which contain a profound analysis of the working of socialism. Over the years Reagan had developed an extensive collection of stories that he attributed to the Soviet people themselves.

One of Reagan’s favorite stories concerned a man who goes to the Soviet bureau of transportation to order an automobile. He is informed that he will have to put down his money now, but there is a 10-year wait. The man fills out all the various forms, has them processed through the various agencies, and finally he gets to the last agency. He pays them his money and they say, ‘Come back in 10 years and get your car.’ He asks, ‘Morning or afternoon?’ The man in the agency says, ‘We’re talking about 10 years from now. What difference does it make?’ He replies, ‘The plumber is coming in the morning.’

Reagan could go on in this vein for hours. What is striking, however, is that his jokes were not about the evil of communism so much as they were about its incompetence. Reagan agreed with the hawks that the Soviet experiment, which sought to transform human nature and create a ‘new man,’ was immoral. At the same time, he saw that it was also basically foolish. Reagan did not need a Ph.D. in economics to recognize that any economy based upon centralized planners dictating how much factories should produce, how much people should consume and how social rewards should be distributed was doomed to disastrous failure. For Reagan the Soviet Union was a’sick bear,’ and the question was not whether it would collapse, but when.

Sick bears, however, can be very dangerous. They tend to lash out. What resources they cannot find at home, they seek elsewhere. Moreover, since we are not discussing animals but people, there is also the question of pride. The leaders of an internally weak empire are not likely to acquiesce to an erosion of their power. They typically turn to their primary source of strength: the military.

Appeasement, Reagan was convinced, would only increase the bear’s appetite and invite further aggression. Thus he agreed with the anti-Communist strategy for dealing firmly with the Soviets. But he was more confident than most hawks in his belief that Americans were up to the challenge. ‘We must realize,’ he said in his first inaugural address, ‘that…no weapon in the arsenals of the world is so formidable as the will and moral courage of free men and women.’ What was most visionary about Reagan’s view was that it rejected the assumption of Soviet immutability. At a time when no one else could, Reagan dared to imagine a world in which the Communist regime in the Soviet Union did not exist.

It is one thing to envision this happy state, and quite another to bring it about. The Soviet bear was in a ravenous mood when Reagan entered the White House. In the 1970s the Soviets had made rapid advances in Asia, Africa and South America, culminating with the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Moreover, the Soviet Union had built the most formidable nuclear arsenal in the world. The Warsaw Pact also had overwhelming superiority over NATO in its conventional forces. Finally, Moscow had recently deployed a new generation of intermediate-range missiles, the giant SS-20s, targeted at European cities.

Reagan did not merely react to these alarming events; he developed a broad counteroffensive strategy. He initiated a $1.5 trillion military buildup, the largest in American peacetime history, which was aimed at drawing the Soviets into an arms race he was convinced they could not win. He was also determined to lead the Western alliance in deploying 108 Pershing II and 464 Tomahawk cruise missiles in Europe to counter the SS-20s. At the same time, Reagan did not eschew arms control negotiations. Indeed, he suggested that for the first time the two superpowers drastically reduce their nuclear stockpiles. If the Soviets would withdraw their SS-20s, the United States would not proceed with the Pershing and Tomahawk deployments. This was called the ‘zero option.’

Then there was the Reagan Doctrine, which involved military and material support for indigenous resistance movements struggling to overthrow Soviet-sponsored tyrannies. The administration supported such guerrillas in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Angola and Nicaragua. In addition, it worked with the Vatican and the international wing of the AFL-CIO to keep alive the Polish trade union Solidarity, despite a ruthless crackdown by General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s regime. In 1983, U.S. troops invaded Grenada, ousting the Marxist government and holding free elections. Finally, in March 1983 Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a new program to research and eventually deploy missile defenses that offered the promise, in Reagan’s words, of ‘making nuclear weapons obsolete.’

At every stage Reagan’s counteroffensive strategy was denounced by the doves. The ‘nuclear freeze’ movement became a potent political force in the early 1980s by exploiting public fears that Reagan’s military buildup was leading the world closer to nuclear war. Reagan’s zero option was dismissed by Strobe Talbott, who said it was ‘highly unrealistic’ and offered ‘more to score propaganda points…than to win concessions from the Soviets.’ With the exception of support for the Afghan mujahedin, a cause that enjoyed bipartisan support, every other effort to aid anti-Communist rebels fighting to liberate their countries from Marxist, Soviet-backed regimes was resisted by doves in Congress and the media. SDI was denounced, in the words of The New York Times, as ‘a projection of fantasy into policy.’

The Soviet Union was equally hostile to the Reagan counteroffensive, but its understanding of Reagan’s objectives was far more perceptive than that of the doves. Commenting on the Reagan arms buildup, the Soviet journal Izvestiya protested, ‘They want to impose on us an even more ruinous arms race.’ General Secretary Yuri Andropov alleged that Reagan’s missile defense program was ‘a bid to disarm the Soviet Union.’ The seasoned diplomat Andrei Gromyko charged that ‘behind all this lies the clear calculation that the USSR will exhaust its material resources…and therefore will be forced to surrender.’ These reactions are important because they establish the context for Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascent to power in early 1985. Gorbachev was indeed a new breed of Soviet general secretary, utterly unlike any of his predecessors, but few have asked why he was appointed by the Old Guard. The main reason is that the Politburo had come to recognize the failure of past Soviet strategies.

The Soviet leadership, which initially dismissed Reagan’s promise of rearmament as mere saber-rattling rhetoric, seems to have been stunned by the scale and pace of the Reagan military buildup. The Pershing and Tomahawk deployments were, to the Soviets, an unnerving demonstration of the unity and resolve of the Western alliance. Through the Reagan Doctrine, the United States had completely halted Soviet advances in the Third World — since Reagan assumed office, no more territory had fallen into Moscow’s hands. Indeed, one small nation, Grenada, had moved back into the democratic camp. Thanks to Stinger missiles supplied by the United States, Afghanistan was rapidly becoming what the Soviets would themselves later call a ‘bleeding wound.’ Then there was Reagan’s SDI program, which invited the Soviets into a new kind of arms race that they could scarcely afford, and one that they would probably lose. Clearly the Politburo saw that the momentum in the Cold War had dramatically shifted. After 1985, the Soviets seem to have decided to try something different.

It was Reagan, in other words, who seems to have been largely responsible for inducing a loss of nerve that caused Moscow to seek a new approach. Gorbachev’s assignment was not merely to find a new way to deal with the country’s economic problems but also to figure out how to cope with the empire’s reversals abroad. For this reason, Ilya Zaslavsky, who served in the Soviet Congress of People’s Deputies, said later that the true originator of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness) was not Mikhail Gorbachev but Ronald Reagan.

Gorbachev was widely admired by Western intellectuals and pundits because the new Soviet leader was attempting to achieve the great 20th-century hope of the Western intelligentsia: communism with a human face! A socialism that worked! Yet as Gorbachev discovered, and the rest of us now know, it could not be done. The vices Gorbachev sought to eradicate from the system turned out to be essential features of the system. If Reagan was the Great Communicator, then Gorbachev turned out to be, as Zbigniew Brzezinski put it, the Grand Miscalculator. The hard-liners in the Kremlin who warned Gorbachev that his reforms would cause the entire system to blow up were right.

But Gorbachev had one redeeming quality: He was a decent and relatively open-minded fellow. Gorbachev was the first Soviet leader who came from the post-Stalin generation, the first to admit openly that the promises of Lenin were not being fulfilled. Reagan, like Margaret Thatcher, was quick to recognize that Gorbachev was different.

Even so, as they sat across the table in Geneva in November 1985, Reagan knew that Gorbachev would be a tough negotiator. Setting aside State Department briefing books full of diplomatic language, Reagan confronted Gorbachev directly. ‘What you are doing in Afghanistan in burning villages and killing children,’ he said. ‘It’s genocide, and you are the one who has to stop it.’ At this point, according to aide Kenneth Adelman, who was present, Gorbachev looked at Reagan with a stunned expression, apparently because no one had talked to him this way before.

Reagan also threatened Gorbachev. ‘We won’t stand by and let you maintain weapon superiority over us,’ he told him. ‘We can agree to reduce arms, or we can continue the arms race, which I think you know you can’t win.’ The extent to which Gorbachev took Reagan’s remarks to heart became obvious at the October 1986 Reykjavik summit. There Gorbachev astounded the arms control establishment in the West by accepting Reagan’s zero option.

Yet Gorbachev had one condition, which he unveiled at the very end: The United States must agree not to deploy missile defenses. Reagan refused. The press immediately went on the attack. ‘Reagan-Gorbachev Summit Talks Collapse as Deadlock on SDI Wipes Out Other Gains,’ read the banner headline in The Washington Post. ‘Sunk by Star Wars,’ Time‘s cover declared. To Reagan, however, SDI was more than a bargaining chip; it was a moral issue. In a televised statement from Reykjavik he said, ‘There was no way I could tell our people that their government would not protect them against nuclear destruction.’ Polls showed that most Americans supported him.

Reykjavik, Margaret Thatcher said, was the turning point in the Cold War. Finally Gorbachev realized that he had a choice: Continue a no-win arms race, which would utterly cripple the Soviet economy, or give up the struggle for global hegemony, establish peaceful relations with the West, and work to enable the Soviet economy to become prosperous like the Western economies. After Reykjavik, Gorbachev seemed to have settled on this latter course.

In December 1987, Gorbachev abandoned his previous ‘non-negotiable’ demand that Reagan give up SDI and visited Washington, D.C., to sign the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. For the first time in history the two superpowers agreed to eliminate an entire class of nuclear weapons.

The hawks were suspicious from the outset. Gorbachev was a masterful chess player, they said; he might sacrifice a pawn, but only to gain an overall advantage. Howard Phillips of the Conservative Caucus even charged Reagan with ‘fronting as a useful idiot for Soviet propaganda.’ Yet these criticisms missed the larger current of events. Gorbachev wasn’t sacrificing a pawn, he was giving up his bishops and his queen. The INF Treaty was in fact the first stage of Gorbachev’s surrender in the Cold War.

Reagan knew that the Cold War was over when Gorbachev came to Washington. Gorbachev was a media celebrity in the United States, and the crowds cheered when he jumped out of his limousine and shook hands with people on the street. Reagan was out of the limelight, and it didn’t seem to bother him. Asked by a reporter whether he felt overshadowed by Gorbachev, Reagan replied: ‘I don’t resent his popularity. Good Lord, I once co-starred with Errol Flynn.’

To appreciate Reagan’s diplomatic acumen during this period, it is important to recall that he was pursuing his own distinctive course. Against the advice of the hawks, Reagan supported Gorbachev and his reforms. And when doves in the State Department implored Reagan to ‘reward’ Gorbachev with economic concessions and trade benefits for announcing that Soviet troops would pull out of Afghanistan, Reagan refused. He did not want to restore the health of the sick bear. Rather, Reagan’s goal was, as Gorbachev himself once joked, to lead the Soviet Union to the edge of the abyss and then induce it to take ‘one step forward.’

This was the significance of Reagan’s trip to the Brandenburg Gate on June 12, 1987, in which he demanded that Gorbachev prove that he was serious about openness by taking down the Berlin Wall. And in May 1988 Reagan stood beneath a giant white bust of Lenin at Moscow State University, where, in front of an audience of Russian students, he gave the most ringing defense of a free society ever offered in the Soviet Union. At the U.S. ambassador’s residence, he assured a group of dissidents and ‘refuseniks’ that the day of freedom was near. All of these measures were calibrated to force Gorbachev’s hand.

First Gorbachev agreed to deep unilateral cuts in Soviet armed forces in Europe. Starting in May 1988, Soviet troops pulled out of Afghanistan, the first time the Soviets had voluntarily withdrawn from a puppet regime. Before long, Soviet and satellite troops were pulling out of Angola, Ethiopia and Cambodia. The race toward freedom began in Eastern Europe, and the Berlin Wall was indeed torn down.

During this period of ferment, Gorbachev’s great achievement, for which he will be credited by history, was to abstain from the use of force. Force had been the response of his predecessors to popular uprisings in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. By now not only were Gorbachev and his team permitting the empire to disintegrate, but they even adopted Reagan’s way of talking. In October 1989, Soviet foreign ministry spokesman Gennadi Gerasimov announced that the Soviet Union would not intervene in the internal affairs of Eastern Bloc nations. ‘The Brezhnev Doctrine is dead,’ Gerasimov said. When reporters asked him what would take its place, he replied, ‘You know the Frank Sinatra song ‘My Way’? Hungary and Poland are doing it their way. We now have the Sinatra Doctrine.’ The Gipper could not have said it better himself.

Finally the revolution made its way into the Soviet Union. Gorbachev, who had completely lost control of events, found himself ousted from power. The Soviet Union voted to abolish itself. Leningrad changed its name back to St. Petersburg. Republics such as Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine gained their independence.

Even some who had previously been skeptical of Reagan were forced to admit that his policies had been thoroughly vindicated. Reagan’s old nemesis, Henry Kissinger, observed that while it was George H.W. Bush who presided over the final disintegration of the Soviet empire, ‘it was Ronald Reagan’s presidency which marked the turning point.’

We are now living in a new world, in which Islamic fundamentalism and radicalism may be replacing Soviet communism as the main challenge facing America and the West. Even as we face our new challenges, however, we should reserve a measure of admiration and gratitude for Reagan, the grand old warrior who led the United States to victory in the Cold War.

This article was written by Dinesh D’Souza and originally published in October 2003 issue of American History Magazine.