At Riga in 1917, the German Eighth Army showed the Russians how it’s done.

The German army offensive to capture the Latvian seaport city of Riga and destroy the Russian Twelfth Army was one of the most complex—and meticulously planned—operations of World War I. It required a combat crossing of nine divisions at the Düna River, which was strongly defended by successive trench lines of the Russian army. Based on operational surprise and initiative, the German plan called for a massive artillery barrage with large quantities of poison gas, just before the attack on September 1, 1917. Assault units would then break through the Russian lines on a three-division front to outflank Riga and trap the Russian army.

The leading strategist for Germany’s Ober Ost—Eastern Front—its chief of staff, Colonel Max von Hoffmann, believed that such an attack on the enemy lines at Riga offered a superb chance to deliver the blow that would knock the Russians out of the war. A decisive defeat of their army on the northwest front and the loss of Riga would crush the already shaky Russian morale. Wrecking the Russian army’s forces there would also open the way for a German advance directly on the capital, St. Petersburg. The Germans believed that, with the Russian capital threatened, the Provisional Government would have little alternative but to sue for an armistice.

By late summer 1917 the Russian army, and the war effort in general, was in terrible shape. Earlier in the war, the army had suffered repeated high-casualty defeats at the hands of the Germans—at Tannenburg in 1914 and Masurian Lakes and Gorlice in 1915—but it had shown surprising skill in recovering and continuing to mobilize vast reserves of manpower. Though there were persistent supply problems in 1917, the Russian war economy continued to produce respectable quantities of arms and ammunition, and its railroads were still able to move men and matériel.

In March, following the revolution that brought down the tsar and ended the 300-year-old Romanov dynasty, there had been great public optimism that the new democratic government would turn the tide of the war. But the Provisional Government’s reforms had created a breakdown in discipline in most of the army, and morale was at a low point by late summer.

Meanwhile, the Germans had their own problems. All of their military operations were governed by the fact that they were fighting a war on two (or with Italy, three) fronts, and the Western Front always had priority. In the East the Germans were always heavily outnumbered, so they were confined to economy-of-force operations carried out with limited troops and supplies. Those thinly spread German forces could only conduct major operations if the High Command (Paul von Hindenburg and Eric Ludendorff) approved the transfer of army divisions from the West to the East.

DURING THE TOUGH 1917 battles in the West, the High Command was loath to transfer units unless an emergency justified it. Eight German divisions were transferred from the Western theater, for example, to ensure that the army had enough forces to rally the Austro-Hungarians and mount a successful counterattack against the Russian offensive Aleksandr Kerensky launched in July 1917, but Hindenburg and Ludendorff made it clear to Ober Ost that when the Kerensky offensive was broken, those divisions would be sent back west again. At that point, however, Hoffmann requested that they be kept a few weeks longer to enable him to undertake his planned September operation at Riga. Judging that strategy a sound and possibly decisive one, the High Command approved the retention of several divisions in the East in August.

Hoffmann noted in his memoirs that General Otto von Below, former commander of the German Eighth Army, had long been in favor of a such an attack and had already picked the best site for an advance to cut off the Russian Twelfth Army defending the Riga front—the village of Üxküll, about 20 miles southeast of Riga on the Düna River.

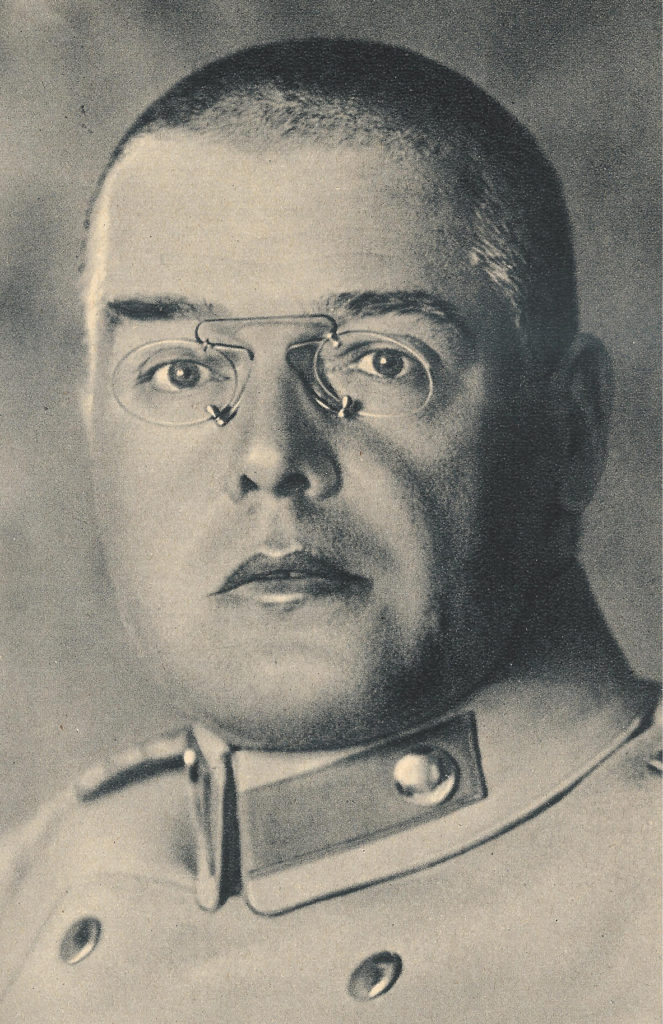

Ober Ost, under the command of Prince Leopold of Bavaria and Colonel Hoffmann, selected two innovative and outstanding leaders to plan and direct the operations of the Eighth Army. General Oskar von Hutier, who had won a solid reputation as a corps commander on the Eastern Front, was given command of the Eighth Army, while Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmüller took command of the Eighth Army’s artillery for the attack. Bruchmüller, a retired major in 1914, had been recalled for duty and had proven himself a genius at organizing artillery for large-scale operations. He had won the Orden Pour le Mérite (the Blue Max) in early 1917 for his brilliant planning and command of the artillery in two corps-level attacks that had resulted in Russian defeats and minimal casualties for the Germans. Now he would be given an army’s worth of artillery to command and receive artillery reinforcements from across the Eastern Front.

To achieve surprise, the German assault forces would be prepared well behind the front and moved into the assault sectors the night before the attack. The attack would be preceded by Bruchmüller’s trademark artillery plan, which was a centrally directed and brief but very intense artillery barrage. The initial assault, crossing the Düna River to storm the Russian positions, would be carried out by specially trained assault companies armed with flamethrowers, light machine guns, and rifle grenades. The first-wave regiments would be accompanied by infantry guns—captured Russian 76.2mm fieldpieces, lightened, cut down and fitted with short-range sights—to serve as direct-fire weapons to eliminate Russian strongpoints. The assault units would utilize the German air service’s close-support tactics and organization that had been used in Flanders since June. The object was to penetrate the Russian defensive lines as quickly as possible and push northeast with nine divisions to the Gulf of Riga, cutting the road and rail lines that connected the Twelfth Army to Russia and trapping it, holding its front line.

The Russian front from Riga southeast to Jakobstadt, in central Latvia, was the best-protected sector of the Eastern Front. A belt of two defensive lines with successive trenches, strong points, and dug-in artillery lay just under two miles apart. The Russians held a bridgehead over 15 miles deep directly west of Riga and along the Düna River. Swamps in the region limited the approaches, but the Russians considered it the most likely area for a German advance because the steel rail bridge over the Düna would be a huge asset for the Germans if they could seize it intact. South of the bridgehead, the front line followed the river. The strong Russian defenses at Üxküll were backed up by a 100- to 165-foot-high ridgeline behind the first trenches, so the Russians had good fields of fire. On the other hand, the German side of the river was heavily wooded with ample cover for their preparations prior to the attack.

ACHIEVING THEIR PLANNED breakthrough would require very effective fire support. Bruchmüller was pulled from Galicia in early August and sent to the Eighth Army to develop the artillery and fire support plan for the battle. The Eighth Army had already done key preparatory work, developing detailed maps of the battlefront that showed every Russian position and defensive line, as well as all command posts and even buried telephone cables. The Germans also had a highly efficient logistics infrastructure to support the attack. Since occupying the western Latvia region of Kurland in 1915, they had made extensive infrastructure improvements in the province, including rebuilding and expanding rail lines, developing the port of Libau (captured in May 1915) as a major logistics base, and building a network of permanent airfields near the Riga front. The Germans’ rail network was such that in 1917 they could move whole divisions from the Western Front to Latvia in under a week.

German air superiority allowed their reconnaissance fliers relatively easy access to Russian territory. Their high-altitude aircraft could fly above the ceiling of the Russian fighters, photographing Russian front lines and monitoring rail traffic and other movements in the region. The invention of the automatic serial camera in 1916 meant that, at the press of a button, German fliers could photograph a kilometer at a time, allowing them to map the entire region in detail and identify all Russian artillery positions and strongpoints. German intelligence was extremely thorough; they knew not only the units opposing them but the location of each battalion and regimental command post.

The German divisions that were to lead the assault were moved to central Kurland, well behind the Riga front, where they spent two weeks rehearsing for the operation. Getting a large force across a heavily defended river required operational surprise to keep casualties at reasonable levels, and the Germans took every precaution to ensure that their attack on Riga would be a total surprise. It was the most complex operation they had yet undertaken on the Eastern Front, and success relied on sending the first wave as squad-size assault units across the 1,300-foot-wide river to establish a bridgehead. To get it right, German units rehearsed with their boats on Latvian lakes well away from the front. The heavy forests of Kurland were good for hiding troops and matériel from Russian aerial reconnaissance—which was generally ineffective. As a result, the Russians failed to spot the German buildup.

The attack called for the assault force to cross the Düna at Üxküll on September 1, then move forward and create a wide bridgehead on the flanks of the Russian defense line, which consisted of the 19th Reserve Division, the 14th Bavarian Rifle Division, and the 2nd Guards Rifle Division. At the same time, the Russian bridgehead would face a diversionary attack by one German division to focus enemy attention to the north. Once the Germans had established their own bridgehead on the far side of the river, a pontoon bridge was to be built in each division sector and the rest of the division, the support forces, and supporting artillery brought over. A second-wave of three more divisions would follow on the same day. Then on September 2, three more divisions would follow.

PRIOR TO THE RIVER CROSSING, German artillery would hammer the enemy line. The artillery plan, conceived by Bruchmüller, was the final evolution of a system that had been developing on the Eastern Front since the 1915 battle for Gorlice. It was based on achieving surprise by opening fire without prior gun registration and instead to register the locations of the enemy’s return fire “on the fly.” The first Russian rounds fired would be noted, then the German batteries would correct their fire and pour a large mass of it on the enemy artillery to suppress counter-battery fire. The Germans would progress to key defensive positions and end with an intensive bombardment of the Russian front lines. Bruchmüller’s plans were very detailed, with all the artillery missions spelled out and assigned to specific task-organized artillery groups. Some German batteries were assigned to fire interdiction barrages on the flanks of the sector to be attacked, to prevent reinforcement by the enemy at the breakthrough point. The goal of Bruchmüller’s plan was to suppress Russian artillery and enable the Germans to cross the river.

The plan also called for centralizing most of the German Eighth Army guns and reinforcing them with heavy guns and mortars from the whole length of the Eastern Front. All guns were placed under Bruchmüller’s command and task organized into groups, each to concentrate on different targets. Bruchmüller had 152 batteries of artillery, a total of 615 guns, in the breakthrough sector. The guns were organized into four artillery groups: Group A was to suppress enemy artillery; Groups B and C were given targets in the breakthrough area, including strongpoints, command posts, and depots, and were to fire barrier barrages to prevent Russian reinforcement in the breakthrough zone; Group D was to provide barrier and flanking fire to cut off the defending Russians. Bruchmüller also organized the 230 heavy and medium mortars into a separate mortar brigade under his command.

The initial artillery assault would consist of five phases, lasting for five hours and 10 minutes. The first phases would be directed against the Russian artillery positions and employ mostly gas rounds (a mix of irritant agents and phosgene rounds that were nonpersistent, so that no lingering effects would impede the advancing Germans). The gas attacks would force the Russians to abandon their guns. While some guns continued the counterbattery fire, the other phases would direct more high explosives and shrapnel at the Russian positions. Finally, right before the river crossing, the Russian front trenches would be subjected to a massive barrage.

When the German assault troops took the first trenches, they were to fire signal flares and the German artillery would conduct a creeping barrage ahead of the German infantry’s advance. More than 500,000 shells would be fired on the day of the assault. (After the war Bruchmüller published the complete fire-support plan for this attack in his book Die Artillerie beim Angriff im Stellungskrieg. David Zabecki also analyzes the plan in detail in his book Steel Wind.)

As the Germans advanced through the Russians’ second defensive lines some of the guns would revert to divisional command. After breaking through two thick belts of Russian trenches and strong points, the army would drive north to the Gulf of Riga. The attack would thus move from a breakthrough to a battle of maneuver in the open after the second line of Russian defenses was pierced. It was a complex plan that required all units to understand their roles and especially the need to shift fire to new targets at the appropriate time. To ensure precision, Bruchmüller personally visited the units involved and explained the plan to artillery and infantry officers—even down to senior NCOs.

THOUGH THE GERMANS had only a few hundred aircraft to cover the vast Eastern Front, since 1916 they had had five squadrons of reconnaissance and observation planes in the Riga sector with the main airfield at Tuckums, less than 30 miles from Riga. In Kurland the German air service based a detachment of riesenflugzeuge (giant airplanes)—four-engine aircraft capable of carrying two-ton bomb loads a long distance—that were used to attack the Russian navy and installations in the area of Riga and the Gulf of Riga. They also established a school for the artillery-plane crewmen to teach them to plot the fall of German shells and report and adjust fire by Morse code radio messages to artillery headquarters. In addition, the German navy maintained air squadrons at Kurland bases to carry out attacks on the Russian fleet and provide reconnaissance service; since 1915 naval aircraft had also supported army operations. At least one fighter squadron, Jagdstaffel 81, provided escort for German observation planes and patrolled the front to seek and destroy any encroaching Russian planes.

Throughout the war, most German planes in the East were two-seater observation and artillery-spotting planes. As the German air service grew rapidly on the Eastern Front in 1917, the number of artillery observation squadrons on the Eastern Front had been increased to 44. In addition to the reconnaissance and artillery planes, two new types of air units appeared at the front—the infantry plane and the battle plane. Both were nimble two-seaters that carried three machine guns. The infantry planes were equipped with radios and used to fly at low level above the battlefield and report back to division headquarters on the positions of the German attackers. The battle planes were organized in squadrons of six aircraft that carried light bombs as well as machine guns. Their mission was to fly as a group and to attack enemy artillery positions and any mass of troops assembling for a counterattack. Both types of planes had nickel-steel armor to protect engines and aircrews from ground fire.

An important feature of Bruchmüller’s fire plan included the German Luftstreitkräfte, the German air force: Each of the three assault divisions was assigned a flight of three infantry planes to provide timely situation updates, a flight of battle planes to provide close-air support, and a flight of artillery planes to help spot fire for the German artillery once the medium and light guns reverted to corps and division control. In all, something close to 200 operational aircraft would support the offensive.

The Russian air service had always been a small force with few operable aircraft, and along the Riga front, it had concentrated its efforts in the south, as had the Germans. In May and June 1917 alone it had lost 40 fighters and 20 fighter pilots— fully half of its fighter force. However the Russians tried, they were unable to contest German air superiority. One German commented after the September 1917 battle for Riga, “Our air superiority brought for the infantry and artillery great advantages, especially in attacking ground targets. The protection from enemy artillery spotters was guaranteed.”

THE ACTUAL ATTACK ON RIGA was almost anticlimactic. The fire support plan worked exactly as anticipated: In the breakthrough sector the Russian artillery was almost completely suppressed and before the German river crossing, the Russian front lines were subjected to a veritable storm of fire. At precisely 0910 German boats were in the water and soon the assault companies—storm troops—were in the Russian front lines, with few casualties.

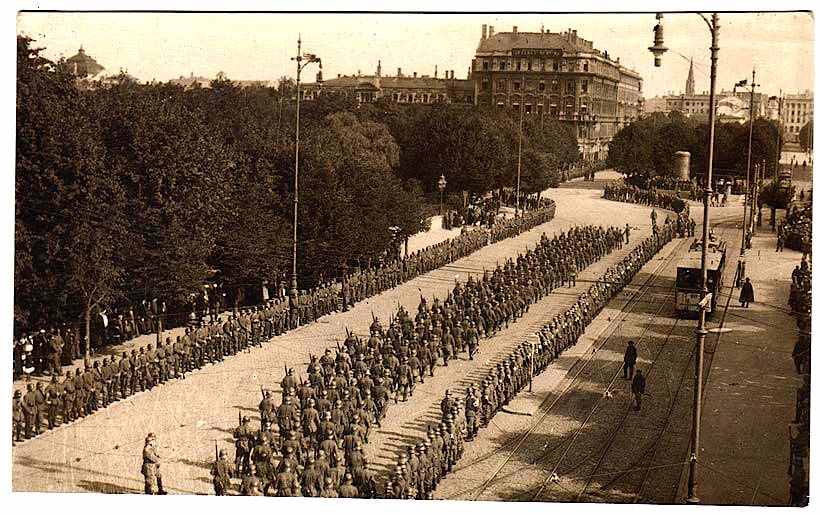

The second wave of infantry crossed as the assault units pressed forward, but the flamethrower, rifle grenade, and light mortar teams were almost unnecessary as the Russians who survived the initial barrage either fled or surrendered to the first Germans they saw. Within an hour of the assault, German engineers were building a pontoon bridge in each assault division’s sector. Before noon German divisions were crossing with their artillery, supplies, transport, and support units. According to plan, the Germans were able to put six divisions across the Düna River on September 1, with three more divisions to follow September 2.

Seeing the German breakthrough, the Russian Twelfth Army abandoned Riga en masse and fled east. The Russian divisions in the bridgehead west of Riga evacuated that entire sector the night of September 1, leaving their guns behind. As the Germans advanced, most of the Russian troops who did not quickly surrender simply ran, often abandoning their guns and heavy equipment. On September 2, as the Russian army evacuated Riga, they paused only to loot shops on the main city streets.

The German drive to cut off Riga proceeded quickly until the Germans ran into the 2nd Latvian Rifle Brigade, which had established a hasty defense along a stretch of the Klein Jägel River southeast of Riga and behind the Russian defense belts. There the Latvians, about 8,000 men strong, managed to hold up the Germans in the late afternoon and morning of September 1 and 2. It was one of the few Twelfth Army units to stand and fight at Riga. Despite suffering heavy casualties—up to 50 percent for some regiments—the Latvians’ resistance gave the Russians time to flee.

The Russians in the bridgehead west of the city were given the order to retreat by late afternoon of September 1, and when the Germans sent out patrols on the morning of September 2, they found the Russian defenses empty. Most of the Russian Twelfth Army survived only because its men made no attempt to fight the Germans.

The retreating army left large numbers of guns that the Germans claimed—325 artillery pieces in all—as well as heavy equipment, rail cars, locomotives, supplies, wagons, and motor vehicles. The Germans entered Riga on September 3, less than 60 hours after the German advance began, and continued to pursue the Russians, who fought only one minor delaying action on September 5.

WHEN RIGA WAS TAKEN on September 3, the German High Command ordered the operation to end, as the Eighth Army’s divisions were needed on the Western Front. In Flanders, the British Army was maintaining its slow advance and the German Fourth Army required reinforcements. Within a week, three divisions from the Eastern Front were on their way west. So even though the Russian army was fleeing east in considerable disorder and a strong pursuit could have assured the full destruction of the Twelfth Army, the Riga offensive was called off. The reduced German army did pursue the Russians for some 30 miles beyond Riga before the campaign finally ended, and the Germans established a defensive front, waiting for the Russians to ask for peace terms.

The capture of the critical Latvian port and the loss of 25,000 Russians, as well as the loss of vast stores of supplies and equipment and most of the Twelfth Army’s artillery, was considered enough of a victory for the moment. But Colonel von Hoffmann noted that a German advance easily could have been continued all the way through the Baltic States.

In terms of tactical and operational innovation, Riga was the first campaign of the war in which all the best practices in infantry, artillery, and air tactics were brought together in one comprehensive campaign plan. And it worked brilliantly.

The most innovative aspect of the Riga operation was the centralization of all artillery and heavy and medium mortar fires—over 800 tubes—under one command and following a carefully phased plan. Firing without registration reduced accuracy, but the sheer volume of fire and the heavy use of gas ensured that the goal of the fire plan—to suppress the enemy artillery and defenses—was achieved. The fire plan for Riga is also noteworthy for including air units for close-air support and battlefield liaison into the overall scheme. Riga was very much a joint operation in the modern sense. Soon after Riga, in October 1917 when the Eighth Army invaded the Estonian islands, the German operation order also called for a separate air annex for army and navy air units flying in support. The air plan of the October 1917 operation included a list of key targets and a radio communications net to coordinate the navy, army, and air units in the most successful amphibious operation of World War I. In short, German doctrine of 1917 was highly advanced and superior in most respects to the doctrine of the Western Allies.

What Riga also showed is that officers like Hutier and Bruchmüller were well informed about developments on other fronts and ready to apply practices known to be effective. Riga is proof that good ideas were circulated very quickly through the German senior leadership. Techniques used only weeks before in the West were applied at Riga. The campaign plan worked largely because the assault divisions were given more than two weeks to rehearse the operation; all the artillery and infantry units were carefully briefed by the higher commanders before the operation; steps were taken to avoid Russian air reconnaissance. In short, the German preparations at every level were thorough and the intelligence preparation exceptional.

After Riga, Hutier and Bruchmüller were brought to the Western Front, where the techniques proven in Riga were further refined. Bruchmüller’s centralized and phased artillery plans were highly successful in the West. The Germans pulled whole divisions out of the line and trained them in assault tactics in the weeks before the 1918 offensives. The same care was used to take the enemy by surprise, and the same level of intelligence preparation applied in the West. Although the Germans eventually lost, the initial success of their 1918 offensive, which followed on the Riga tactics, shocked the Allies. Tactics that had broken a demoralized Russian army at Riga worked nearly as well against a well-equipped and not demoralized British Fifth Army in March 1918.

James S. Corum, dean of the Baltic Defence College in Estonia since 2009, is the author of 11 books on military history, air power, and low-intensity conflict. His Handbook of World War I Air Forces is scheduled for publication in 2015.

Originally published in the October 2014 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.