The Earl of Dunmore stamped his name on a 1774 Indian war and took credit for its success, earning the lasting enmity of the Virginia militiamen who actually fought.

The Earl of Dunmore stamped his name on a 1774 Indian war and took credit for its success, earning the lasting enmity of the Virginia militiamen who actually fought.

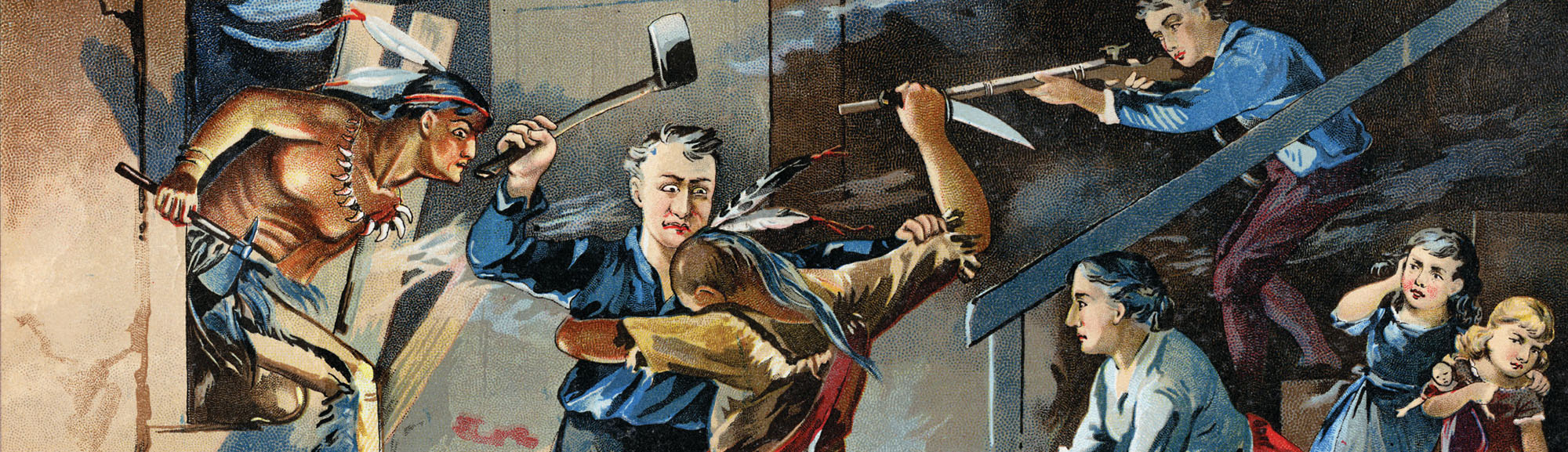

What could be considered the opening shots of the American Revolution came not at Lexington and Concord, Mass., in April 1775 but six months earlier and 750 miles southwest at a spot called Point Pleasant, at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha rivers (in present-day West Virginia). The only battle in a five-month conflict known as Lord Dunmore’s Warsaw besieged Virginia militiamen drive off a combined force of Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware, Wyandotte and Cayuga Indians. In one of those fateful ironies of history the nominal commander of the Virginians, a man who stamped his name on the conflict, would become their bitter enemy less than a year later.

John Murray, fourth Earl of Dunmore, received his baptism by fire long before the engagement at Point Pleasant.

Born in 1730 in Tymouth, Scotland, Murray at the tender age of 15 became a page to Charles Edward Stuart, “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” and was present at the Jacobite pretender’s crushing defeat by the British at Culloden in 1746. After that historic battle Murray’s immediate family was put under house arrest, his father, William, imprisoned in the Tower of London. In 1750 William Murray received a conditional pardon, and son John, 20, joined the British army. In 1756, after the deaths of both his uncle and father, John Murray became the fourth Earl of Dunmore. In the late 1760s he moved his young family to the American colonies and in 1770 was appointed governor of New York. When the governor of Virginia died the following year, Dunmore—who had excellent connections in London through brother-in-law Granville Leveson-Gower, the second Earl of Gower—was appointed to replace him.

The Virginia Dunmore inherited was the largest and most populous British colony in North America, its 600,000 residents (40 percent of whom were slaves) spread from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean across vast tracts of rich farmland to the west of the Allegheny Mountains, the latter region purchased under treaty in 1768 from the Cherokee Nation and the Iroquois Confederacy. Dunmore himself was looking to get rich and shortly after his arrival used his privileged position to acquire 100,000 acres of the former Indian land.

Expansion of the Virginia colony west of the Alleghenies sparked conflict with the Ohio Indians—especially the Shawnee, who had repeatedly sought to unite the Ohio tribes against the encroaching whites. Mutual hostility presaged several violent confrontations, the most infamous occurring in 1773 when then obscure frontiersman Daniel Boone and some 50 other settlers sought to create the first permanent settlement in Kentucky. That October a supply party of eight men and boys was en route to meet up with Boone’s main group when ambushed by a band of Delawares, Shawnees and Cherokees. Two of the party managed to escape. The others—including Boone’s eldest son, 17-year-old James—were tortured to death. That and similar incidents led Dunmore to declare war in May 1774 “to pacify the hostile Indian war bands.”

The Virginia governor’s main opponent was Chalakatha Shawnee Chief Hokelesqua, or Cornstalk. In his mid-50s, Cornstalk was an experienced warrior who had led his braves to victory over British Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock’s troops at the 1755 Battle of the Monongahela during the French and Indian War. Cornstalk had also fought at Bushy Run in 1763 and led numerous other raids on hunting parties and settlements during Pontiac’s Rebellion. In the coming clash at Point Pleasant he would command an estimated 425 Shawnees, 150 Mingos and 125 warriors from other bands and again prove himself a highly competent combat leader.

For a soldier steeped in European military tradition, Dunmore showed unusual foresight in his plans for a campaign in the American wilderness—a campaign in which he was determined not to repeat the mistakes that had plagued British forces in the early years of the French and Indian War. Unable to use regular troops, Dunmore recruited two separate militia forces, dubbed the Northern and Southern armies. The 1,200-man Northern army, under his personal command, consisted of militiamen already west of the Alleghenies, while those of the 1,100-man Southern army hailed from southwestern Virginia—a logical choice, as established trails led from there directly to the Ohio Valley. Dunmore had also arranged for well-organized supply trains, each army driving cattle, to be slaughtered on the march, while flour and other staples were to be toted in by packhorse and canoe.

Dunmore’s subordinates were largely experienced officers, many veterans of the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Rebellion, and included such future Revolutionary War notables as Daniel Morgan and George Rodgers Clark. Moreover, the majority of Dunmore’s men were well versed in backwoods survival skills, wore suitable gear for the rough terrain and supplied their own weapons and ammunition.

Despite his thorough planning, however, Dunmore made a potentially disastrous decision at the outset of the campaign. Believing the mere presence of a large body of armed men would compel the Indians to seek peace terms, he chose en route to redirect his Northern army and encamp on the Ohio at the mouth of the Hocking (present-day Hockingport, Ohio), a site suitable for a peace conference. Meanwhile, the Southern army commander, Colonel Andrew Lewis, naturally assuming the objective was to engage and decisively defeat the largest possible number of Indians, marched his men toward his enemies’ main villages and encamped at the agreed-on rendezvous spot at Point Pleasant, at the junction of the Kanawha and Ohio—two days’ canoe ride downriver from Dunmore’s new endpoint.

Why Dunmore failed to convey his intentions to Lewis remains unknown. One theory suggests he deliberately left the Irish-born Virginian to his own devices. Tensions between Britain and the colonies were on the rise at the time, and Dunmore may have considered that allowing the Indians to wipe out Lewis’ force would be an effective way of eliminating a large number of would-be enemies—men whose experience would make them indispensable to a rebel army. Rumor had it the British commander also may have been courting Indian allies along the Ohio, allies on whom Britain could rely to help put down any subsequent colonial rebellion.

Indian scouts shadowed both militia armies as they moved west, and Cornstalk surely realized Dunmore’s decision to divide his command—by chance or design—offered the outnumbered Indian force an opportunity to defeat the interlopers. Cornstalk and his fellow leaders decided to strike Lewis’ smaller Southern army at Point Pleasant before Dunmore could reinforce him.

Indian scouts shadowed both militia armies as they moved west, and Cornstalk surely realized Dunmore’s decision to divide his command—by chance or design—offered the outnumbered Indian force an opportunity to defeat the interlopers. Cornstalk and his fellow leaders decided to strike Lewis’ smaller Southern army at Point Pleasant before Dunmore could reinforce him.

After a well-organized march of 160 miles in just 19 days, Lewis and his militiamen went into camp at Point Pleasant. The Southern army commander and Dunmore had been in contact through couriers since starting the campaign, but because they’d begun their marches at different times and were moving toward different objectives, neither was certain where the other was at any given time.

On October 9 Lewis received a dispatch from Dunmore instructing him to rendezvous at Pickaway Plains, deep in the Ohio wilderness some 80 miles north of Point Pleasant. Insisting his packhorses needed rest, Lewis replied he would not be able to meet up by the date specified. He did not seem overly concerned at being so far from any reinforcement, a confidence rooted in the knowledge he occupied a strong position—buffered to the south by the Kanawha and to the west by the Ohio—and his belief the majority of hostile Indians were closer to Dunmore than they were to him. His latter assumption was misplaced, for a few miles upriver Cornstalk was preparing to attack.

The Indian leader actually had little enthusiasm for the coming battle. While certain of his warriors’ courage, he realized victory would be a long shot. His force remained outnumbered, and even if his men were able to wipe out Lewis’ force, they would still have to contend with Dunmore’s larger Northern army. With no hope of significant reinforcement, he worried his men would be unable to fight another battle in quick succession. Not wanting to dampen his warriors’ morale, on the night of October 9 Cornstalk led them in war dances. The next morning, an hour before sunrise, he led his force in a long, snakelike column toward the enemy camp.

Though stealthy, Cornstalk’s war party did not go unnoticed—one of Lewis’ pickets spotted the approaching Indians and ran to warn the camp. Cornstalk noticed. Seeking to retain a measure of surprise, he ordered his men to halt in place and prepare to ambush the militiamen he was certain would march out to verify the sentry’s sighting. He deployed the warriors along a narrow front between the Ohio to the west and a 250-foot-high west-facing ridge some 600 yards to the east. Cornstalk knew whichever side reached the top first could dominate the terrain below.

As Cornstalk predicted, two 150-man detachments under Colonels William Fleming and Charles Lewis (Andrew Lewis’ brother) soon marched out to the place where the picket had spotted the Indians. Suddenly, the woods erupted in fire, smoke and singing musket balls. The opening volley killed the detachments’ scouts, wounded Lewis in the chest and felled many of those standing near him. Fleming, too, took a ball to the chest, and both colonels stumbled back to camp. While some of the Virginians broke and ran under the initial onslaught, battle-tested men found cover and fought back the best they could. The few remaining unwounded officers managed to organize a defense, thus preventing the battle from becoming a rout.

As hysterical men streamed back into camp, Southern army commander Andrew Lewis acted with cool determination. He first ordered his remaining 800 militiamen to form companies and march in turn to the relief of the advance troops. He then directed those who had retreated to fell trees and use them to build breastworks.

Although buoyed by their initial success, the Indians lost momentum as militiamen poured to the front. Cornstalk soon realized he faced a battle of attrition he could not possibly win, nor could he turn either of Lewis’ flanks and exploit his warriors’ superior maneuverability. He would have to find another way to break their line.

As the battle wore on, the Virginians found themselves in an unusual position. Long accustomed to war parties that made hit-and-run attacks before melting back into the wilderness, Lewis’ men found themselves fighting a set-piece battle against an Indian adversary who stood his ground. What’s more, Cornstalk and his warriors shouted encouragement to one another and hurled insults in English, calling the militiamen “white dogs” and “sons of bitches.”

The seesaw battle, marked by hand-to-hand single combat, raged into the early afternoon, neither side able to gain the advantage. The tide finally turned, however, when a company of militiamen worked its way along the Kanawha to outflank the Indians and pour heavy fire into their ranks. This proved the final straw for Cornstalk, who ordered a rearguard to keep the Virginians occupied while his main force withdrew. It was impossible to determine the number of Indian casualties, as the survivors dumped many of their dead into the Ohio and carried off the wounded on makeshift litters.

While Lewis’ Southern army suffered some 80 dead—including his brother and Colonel Fleming—and 140 wounded, the Virginians had driven off their attackers. Cornstalk and his allies fled north to their home village near Pickaway Plains.

A week later, after making provision for the wounded and leaving 300 men to safeguard them, Lewis and his remaining militiamen crossed the Ohio to keep their rendezvous with Dunmore. En route a messenger arrived with a dispatch from the earl, informing Lewis treaty negotiations were in progress and ordering his return to Point Pleasant. The indignant Virginian pressed on and was within sight of Cornstalk’s village when Dunmore himself ventured out to meet him and reiterate his orders. Only then did Lewis reluctantly turn his men around and march back to the Kanawha. Within a few weeks the Southern army disbanded.

On October 19 Dunmore and his officers, who had taken no part in the fighting, met with Cornstalk to sign the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, the terms of which stated the Shawnee would cease hunting south of the Ohio and stop harassing settlers along the river. That in turn opened the door to settlement on lands that ultimately encompassed the states of Kentucky and Ohio.

After three months in the field Dunmore returned to Williamsburg, claiming the mantle of victory, while colonists in the know held their tongues in the interest of peace. Within months, however, the gloves came off as tensions escalated between Britain and the colonies. Before marching from the city, Dunmore had dissolved the disaffected Virginia House of Burgesses. In his absence the burgesses had elected delegates to the First Continental Congress, and though Dunmore railed against the rising tide of revolution, he took no decisive action to stop the colony’s rift toward independence. Patrick Henry’s March 1775 “Give me liberty, or give me death!” speech—delivered to Virginians at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond—helped convince colonial officials to approve a resolution calling for armed resistance to British rule.

In November 1775 Dunmore cemented his standing as an enemy of the state by proclaiming martial law and offering freedom to all slaves who abandoned their Patriot masters to join the British. The move prompted tens of thousands of Virginia slaves to escape, an estimated 800 to 2,000 seeking refuge with the “hero” of Point Pleasant. Dunmore promptly organized several hundred of them into his own Ethiopian Regiment. Though he led the unit to victory at Kemp’s Landing, Va., that November 17, the regiment lost decisively at Great Bridge, south of Norfolk, on December 9.

Patriot forces subsequently seized Norfolk, while Dunmore, his troops and panicked Virginia Loyalists sought refuge aboard British ships in the harbor. After a smallpox outbreak wiped out most of his regiment, Dunmore formally disbanded its few survivors. On New Year’s Day 1776 the British bombarded the town in retribution before sailing away. Dunmore briefly set up operations at Portsmouth, but events in his lost colony ultimately prompted him to concede defeat and return to Britain. Regardless, he continued to draw his pay as governor until war’s end in 1783. The ever-proud earl sat in the House of Lords and turned a stint as governor of the Bahamas before dying in his late 70s in 1809.

Virginia educator John Bertrand has written for numerous publications. For further reading he recommends Point Pleasant, 1774: Prelude to the American Revolution, by John F. Winkler.

First published in Military History Magazine’s January issue.