The pain continued for many POWs even after they came home.

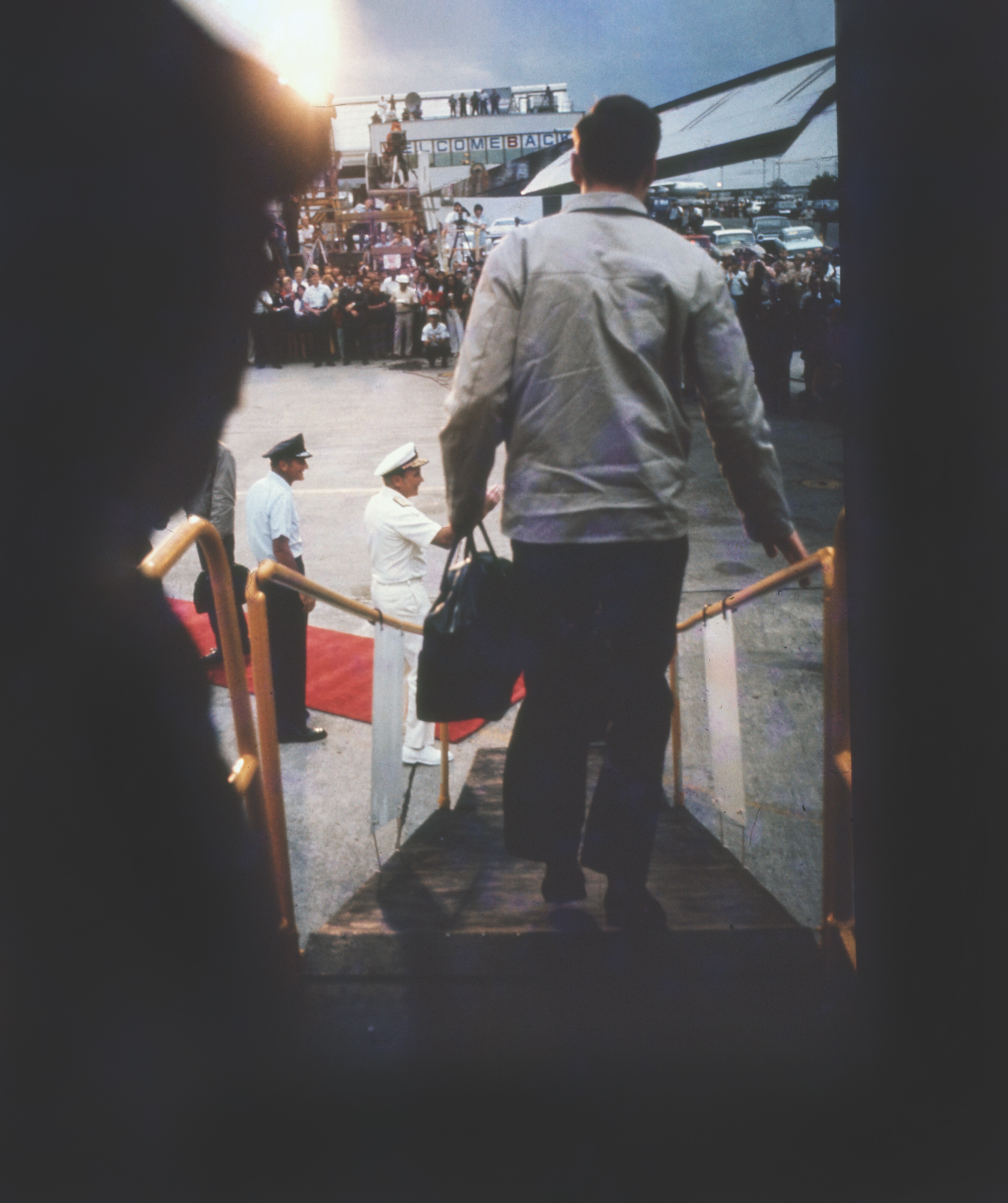

In February and March 1973, dozens of flights on U.S. Air Force C-141A Starlifters began the journey home for 591 prisoners of war in Southeast Asia. The Paris Peace Accords, signed on Jan. 27, 1973, ended the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam and provided for the release of the POWs. Most had been held in North Vietnamese prisons and were freed in Hanoi. Others were freed near Saigon (the release site for Viet Cong captives held in South Vietnam) and Hong Kong (three prisoners who had been held in China).

To ease the POWs’ reentry into American life, the Defense Department created Operation Homecoming, a five-year multifaceted program that included not only the flight home but also procedures to evaluate the physical and mental condition of repatriated prisoners of war, collect data from those RPOWs for use in future wars, and help the men return as much as possible to their former life or move forward in a different direction, with a particular emphasis on reintegration into their family after a long separation.

I participated in that process as a senior Army psychologist working with Army returnees. I had served two tours in Vietnam as a combat infantry adviser (1966-67 and 1968-69). I received seven valor wards, a Purple Heart and an Air Medal. While earning a doctorate in counseling psychology, I wrote my dissertation on the adjustment of Vietnam veterans. Afterward, I continued my research on Vietnam vets.

The first stop on the Operation Homecoming journey was Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Onboard the aircraft were flight surgeons (because most RPOWs were pilots, the planners thought they would prefer flight surgeons to regular physicians), nurses and aeromedical technicians. Over several weeks, 54 flights transported 325 Air Force, 138 Navy, 77 Army and 26 Marine returnees, along with 25 civilians including two German nurses captured outside of Da Nang. One was the only woman POW.

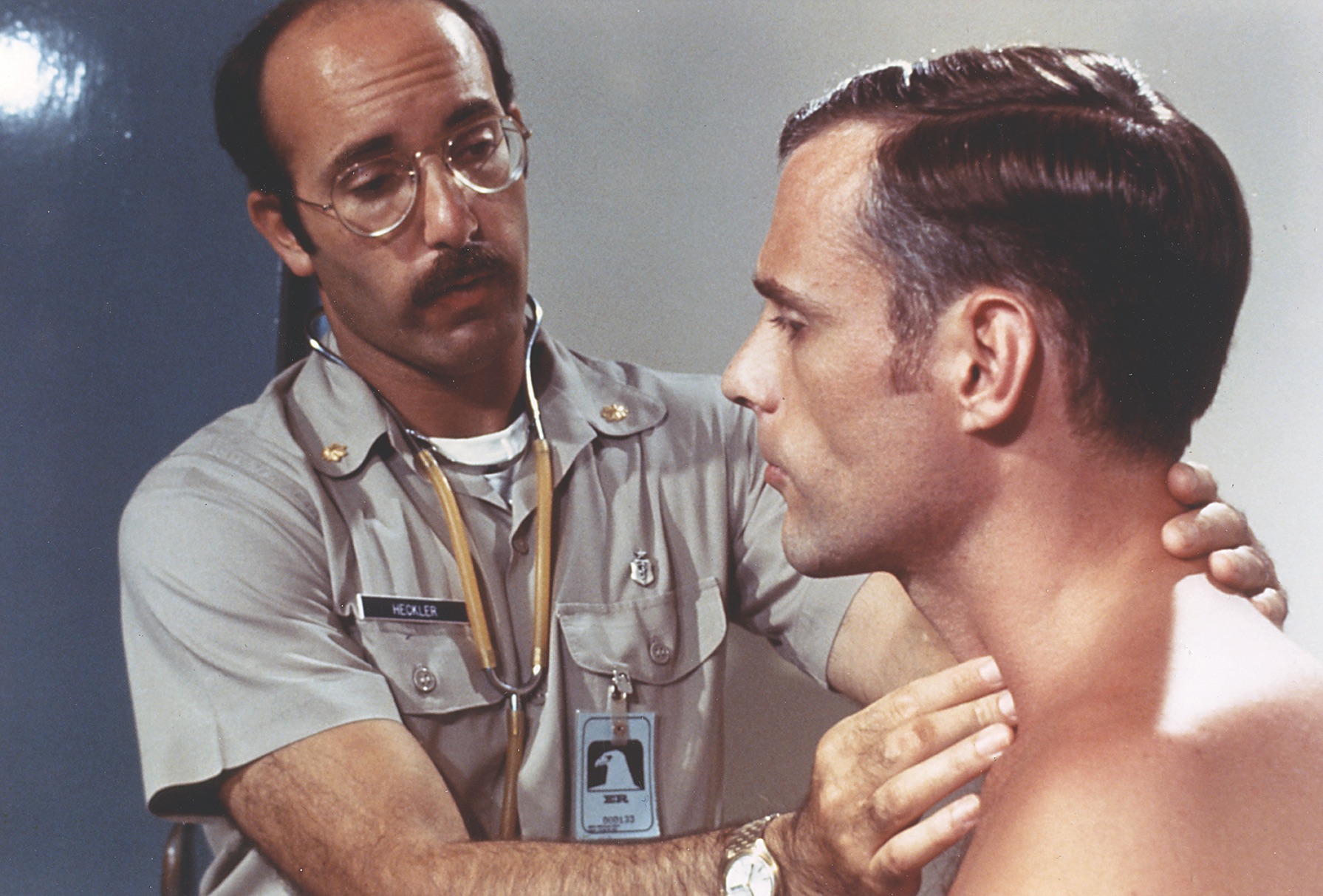

At Clark, the RPOWs called home and visited the base exchange for personal supplies. They also were evaluated medically and psychologically and debriefed. The debriefings were important in getting information on the fate of Americans missing in action and POWs who might have died or perhaps were still alive in Southeast Asia.

Each RPOW talked with a debriefer and an escort, matched as closely as possible to the former prisoner in age, education, background, career experience, interests and family life. The escort was trained to serve as a shock absorber, a buffer to help the man adapt to his sudden shift into a vastly changed world.

The length of the RPOWs’ stay at Clark depended on their health and intelligence debriefings. The goal was to move the men quickly—within days or a week—to military facilities near their homes. They were flown from Clark to California via Hawaii and then transferred to a military hospital or wherever they wanted to go.

While most Americans greeted the returning men openly and warmly, some viewed them not as heroes but rather as war criminals. That antipathy was mostly directed toward crew members on bombers.

In general, the RPOWs had to deal with four major issues: 1) physical damage from torture, improperly healed combat wounds and injuries, malnourishment and the effects of various diseases; 2) the reunion with a family that had changed significantly during the absence of the husband/father; 3) the considerable career gap between them and peers who had not lost the prime years of their work life to captivity; 4) their introduction into a society that did not exist prior to captivity.

All of the Army RPOWs—unlike Navy and Air Force flight crews captured after being shot down over North Vietnam—had been taken prisoner in South Vietnam, and their horrendous treatment at the hands of the Viet Cong resulted in great suffering, including shelters with little protection from extreme climatic conditions, poor nutrition, infections and diseases, beatings and untreated wounds. They were often chained or imprisoned in small cages. Some of the younger RPOWs showed maturation deficiencies due to the malnutrition, disease and infections.

For many POWs returning to their families, the enduring physical problems were not their only concern. The family separations required on some tours and during combat assignments were an accepted part of the job, but the prolonged absence due to captivity added an unknown dimension to family dynamics. Some RPOWs had left toddlers and returned to preteens. Additionally, the role of women in society was undergoing considerable change, exemplified by the women’s liberation movement.

The extended separation put the woman in charge of the family, minus her mate. Some women were able to keep the family together, and some sought relief by bonding with other men. Many saw themselves as captives in their own right because they did not know if they were wives or widows. They were locked in their own prison of loneliness, fear, anxiety, apprehension and dread, facing a future with too many unknowns. A two-parent family became a single-parent household with the mother now totally responsible for the family, maybe forever.

Upon the reunion of RPOWs and their families, spousal views on the roles of husband-wife/mother-father frequently diverged. Often the military husband had made major financial decisions, determined where the family lived, disciplined the children and set the tone family for life. In normal deployments, all of this fell onto the wife temporarily, until the husband returned 12 or 13 months later. But when the man came home after a long captivity, the family had survived and functioned without him for years. Some children had spent most of their young lives without their father. However, the RPOW was still, psychologically, living in a different time.

For many repatriated POWs, the changes during the separation would be so great that the family could never again be a cohesive unit. The reunited members might have totally different perspectives on what the future should be like. Often the bewildered father was no longer needed to head the family. It’s easy to image how strong clashes would occur.

Special Forces Capt. Floyd “Jim” Thompson was captured on March 26, 1964, and repatriated on March 16, 1973, a period of nine years, making him the longest-held POW of the Vietnam War. When Thompson was assigned to Vietnam, his wife, Alyce, and family moved into housing at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. At first, Thompson’s status was unknown, possibly killed in action. Ultimately, his family was told to vacate their quarters at the fort. Alyce Thompson, confused, afraid, lonely, with a family to care for, eventually moved in with another man, and they lived as husband and wife, as recounted by journalist Tom Philpott in his 2001 book Glory Denied.

Thompson was reunited with his wife at Valley Forge General Hospital, an Army hospital near Philadelphia. In Philpott’s book, Alyce Thompson described her 39-year-old husband as “emaciated” and added, “He had gotten so old. White hair. He looked at least sixty.” She said to him, “There is something I have to tell you.” He replied, “I knew something was wrong.” They divorced in 1975.

Many returning POWs had spent their career-building years in the military trying to survive in enemy prisons. Leadership assignments, professional military education and other important aspects of military life escaped them. In the competition for plum positions, they had fallen behind.

During Thompson’s almost nine years in captivity, I advanced from second lieutenant to major. I had served as a platoon leader, executive officer, company commander and battalion staff officer. I graduated from the Army Special Warfare School, the Defense Language Institute and the Officer’s Career Course. I also had earned a master’s degree and was five months away from my Ph.D. Quite a difference.

From the moment of captivity, the POW’s known world ceased to exist. He had not been part of an evolving society in the United States, nor a participant in events there as they were occurring. As new captives were imprisoned, they shared what was happening back in “the world.” Many POWs were unable to emotionally, psychologically or intellectually accept what they were told.

On their return to the United States, they still could not believe what had taken place in America while they were in communist prisons, shut off from the free world. In the late 1960s the hippie movement began (anti-war, free love, open use of drugs, communal living), and by the time the repatriated POWs got home the hippie lifestyle had moved into mainstream American society. The POWs reentered an America that was a much different place. Their world had changed so much that in many cases it no longer existed.

Operation Homecoming’s medical, psychological and social experts were aware that the RPOWs would need help reestablishing family relationships, facing vocational challenges and functioning in an environment foreign to them.

In 1969, the Defense Department had already begun to create plans to assist the POWs once they were released. Because no Americans troops had been imprisoned as long as those in Vietnam, the planners had no comparable data to use. The Navy established the Center for POW Studies, or CPOWS, at the Navy Health Research Center in San Diego in 1971 to conduct research with the families of returning POWs.

The Defense Department also funded a five-year program, running from 1973 through the end of 1978, to evaluate the effects of long-term captivity. Defense Secretary Melvin Laird stated, “I cannot emphasize too strongly the necessity to make every possible effort within our capability to help these men readjust to healthy, normal, productive lives when they return.”

In a memo, Laird said military medical facilities would be established to “diagnose, treat, alleviate and hopefully cure the physical and mental diseases that afflict the returnee and to assist in the counseling that would aid the returnee in adjusting to his position in military or civilian life.”

In 1972 all branches of the military met at CPOWS to develop a standard method for evaluating and treating the returnees and collecting data. Air Force RPOWs went to Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, and Army RPOWs went to Brooke Army Medical Center, also in San Antonio. Navy and Marine RPOWs went to the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute in Pensacola, Florida.

Once a year, for five years, the RPOWs would report to their military hospitals for physical and mental evaluations. After the first two years, several Army RPOWs stopped reporting to the Brooke medical center but were evaluated at Army hospitals in areas where they were stationed. Others sought private care. Not all Army RPOWs completed the five-year program. Some dropped out over time.

In December 1978, CPOWS closed, and Operation Homecoming was terminated in January 1979.

Some of CPOWS’ behavioral scientists believed the closing was premature because the collected data warranted much more analysis, including conclusions and recommendations for the future. As a participant in this program, I can say that as time passed, collection, analysis and documentation of the evaluations gave way to the needs of expediency and efficiency.

Generally, the experiences of Army captives were different from those of most POWs, who were pilots and therefore commissioned officers. Army POWs typically were enlisted men, noncommissioned officers.

Not all Army RPOWs were part of Operation Homecoming. Some had been freed earlier by the North Vietnamese government for propaganda reasons, and others had escaped. They were on their own evaluation schedule after returning to Army control.

One Army escapee, Special Forces Maj. James “Nick” Rowe, who was captured in 1963 and broke free in 1968, described his reintroduction to the outside world in a 1971 book, Five Years to Freedom.

While he was a patient being evaluated at an Army hospital in Vietnam, a nurse handed him a copy of Playboy magazine, saying, “This is the beginning of your therapy.” Rowe thought, “After a five-year drought, this was too much to take all in one visual gulp.” (While serving as U.S. Army adviser to the Philippines government, Rowe, then a colonel, was assassinated by communist guerrilla insurgents in April 1989.)

During the Vietnam War, 179 Army members were captured and imprisoned between Jan. 1, 1961, and Dec. 31, 1976, in all areas of Southeast Asia, according to the Defense Department document Number of Casualties Incurred by US Military Personnel in Connection with the Conflict in Vietnam (Jan. 20, 1977). The 179 included the 77 returned via Operation Homecoming, as well as 57 who were released earlier or escaped and 34 who died in captivity.

The remaining 11 were still classified as POWs as of December 1976, based on the debriefings of returning POWs, who may have seen someone at a POW camp, but that person’s whereabouts was unknown in 1976. Today there are no known POWs in Vietnamese hands.

The 77 Army men released in 1973 consisted of 28 officers and 49 enlisted. The average age when captured was almost 28 for officers and 23 for enlisted. There were 25 aviators or air crew members, 16 infantrymen, 18 Special Forces or combat advisers, seven in transportation and 11 from other Army occupations. By the time of their release, most had been moved into North Vietnamese prisons, but 18 were still in Viet Cong camps in South Vietnam.

The Operation Homecoming evaluations found that many younger RPOWs were not physically, mentally and psychologically equipped for their time as a prisoner. James Daley, age 22, described their plight in his book A Hero’s Welcome, published in 1975. He recalled hearing a prison propaganda recording that ended with the question, “Why die for Old Glory?” It made Daley think of several fellow POWs who died in captivity. “I considered the endless war,” he wrote. “And I couldn’t help but ask myself the very same question.”

The actions of some younger POWs were viewed by senior POWs as collaborating with the enemy to obtain extra benefits, a breach of the military’s Code of Conduct. After the war, some senior RPOWs brought misconduct charges against enlisted men and officers for their behavior.

A Marine sergeant facing charges, one of eight accused enlisted RPOWs in the Marines and Army, committed suicide. At this point the Defense Department stepped in. Investigators found insufficient evidence for the allegations, so all charges were dropped for the remaining two Marines and five soldiers. All branches created committees to evaluate the behavior of the RPOWs. Some were found unqualified for continued service and released from active duty.

Older officers and NCOs, as career soldiers, understood that the danger of being captured was an accepted risk of their chosen vocation and placed value in the Code of Conduct. They also were mostly married. Those strong family ties, combined with military experience and a staunch belief in “the Code,” strengthened their ability to resist and endure. The younger POWs were less educated and experienced, not interested in a military career and didn’t have wives or children to return to. They had a harder time resisting the pressure their captors applied. They did what they could to survive.

The differences in age and rank also came into play when the POWs got home and tried to return to a normal life. The senior, career-oriented officers and NCOs fared best.

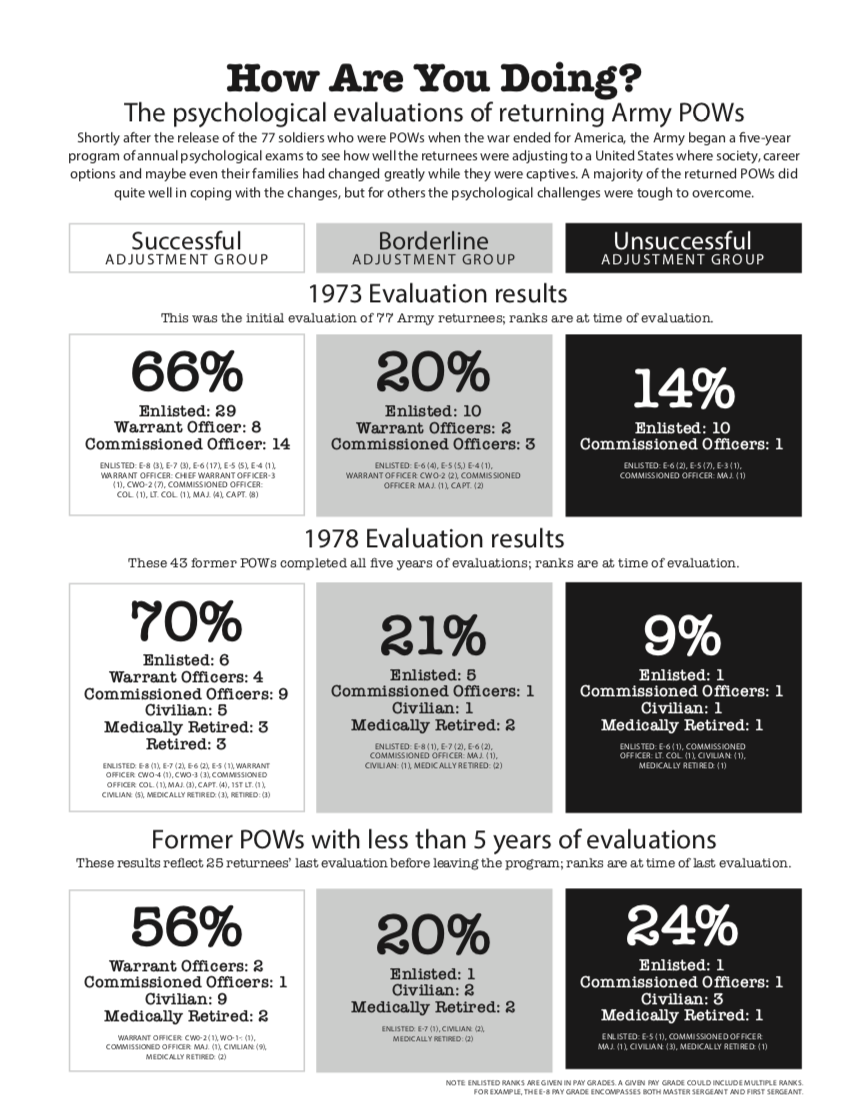

The initial psychological evaluation of the RPOWs consisted of various personality inventories and tests. If the psychologist decided more information was needed, additional testing was done. Based on the clinical evaluation of their post-captivity lives and careers, whether in the military or civilian life, the RPOWs were placed in one of three groups.

The first group, the “successful adjustment” group, consisted of men who were successfully coping with the changing demands of their lives. They did not exhibit any psychiatric disorders. Their social, vocational and family lives were satisfactory and productive.

In the evaluation’s “borderline adjustment” group were men experiencing minor or mild difficulty dealing with career, family or social issues. Some also had mild personality disorders or neuroses. They were functioning and moving along in their lives, but it was hard for them.

The “unsuccessful adjustment” group comprised the RPOWs with severe adjustment difficulties, according to the clinical evaluation. They were diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder or a severe nonpsychotic mental disorder.

In 1973 all 77 Army RPOWs received psychological evaluations during the first three to six months after release. The evaluations indicated that 51 soldiers (66 percent) were successfully adjusting, 15 (20 percent) were experiencing some difficulty adjusting and 11 (14 percent) were encountering severe adjustment problems.

The successful group consisted of 22 officers and 29 enlisted, based on their rank upon repatriation. Because of their length of captivity, many RPOWs were automatically promoted, which meant their repatriation rank was considerably higher than their rank when captured. The borderline group contained five officers and 10 enlisted. In the unsuccessful group were one officer and 10 enlisted.

As time passed, fewer men were evaluated at Brooke medical center. The second evaluation consisted of 74 men. By the time of the final evaluation in 1978, there were just 43 men in the program, including RPOWS who had become civilians (released from active duty), medically retired from the Army or retired normally. In that evaluation, 30 (70 percent) were classified as successful, nine (21 percent) as borderline and four (9 percent) as RPOWs with severe adjustment problems.

Before Operation Homecoming concluded, 25 Army RPOWS chose to not go through the full five years of evaluations. At their last evaluation before dropping out, 14 men (56 percent) were in the successful adjustment group, five (20 percent) were facing some adjustment problems, and six (24 percent) had received a diagnosis of psychiatric problems.

During the five-year evaluations the first two years after repatriation were the hardest for the RPOWs in terms of readjustment to their careers and normal behavioral patterns. The most successful returnees were older when captured and spent less time as POWs than either the borderline or unsuccessful RPOWs.

It is generally accepted that being in combat in Vietnam and becoming a POW was one of the most traumatic experiences a soldier could ever experience. Yet, as the final evaluation in 1978 shows, only 9 percent of Army RPOWs were dealing with severe adjustment problems in their post-captivity lives, while 70 percent were able to reenter society and adjust normally. They were successfully coping with the demands of life, raising families, pursuing careers and enjoying their post-captivity years.

Bob Worthington is a retired Army lieutenant colonel with a doctorate in counseling psychology. He served his last decade in the Army as a senior clinical psychologist, leading the Army RPOW psychological evaluations from 1976 until the final reports in 1979. He is a writer (www.BobWorthingtonWriter.com) with over 2,500 publications. His latest book is Under Fire with ARVN Infantry (McFarland, 2018).

This feature originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. To subscribe, click here.