On the evening of October 29, 1929, a 25-year-old photographer entered the First National Bank of Boston hoping the building would be empty, so she could finish shooting pictures of its new lobby for an advertisement. Instead, she found the lobby swarming with bank officers. Irritated, Margaret Bourke-White tried to shoot around them. Finally, a vice president snapped at her. Didn’t she know the stock market had crashed? Hadn’t she read the papers? She hadn’t. As Bourke-White wrote in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself,“History was pushing her face into the camera, and here I was turning my lens the other way.”

She would not, however, turn away for long. Though Bourke-White started her career with little interest in politics, she went on to photograph an astonishing array of world figures, including General George S. Patton, Josef Stalin, Madame Chiang Kaishek and Mahatma Gandhi at his spinning wheel. The first female photographer for Life magazine at a time when the field was dominated by men, Bourke-White gained celebrity for her daring pursuit of stories and her now-iconic black-and-white photos of world events in the mid-20th century: bread lines during the Depression, concentration camp victims at Buchenwald and exploited gold miners in apartheid South Africa. Yet she became a photographer only as a way to support herself.

Margaret Bourke-White grew up in rural New Jersey, raised by a mother who prized fearlessness and a father constantly tinkering with his latest invention. In her autobiography, she recalls the day her father took her to a factory where printing presses were made: “In a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy. To me at that age, a foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty.”

She entered college planning to become a scientist. Half a dozen schools and one failed marriage later, she found herself at Cornell, unable to pay the bills. When she couldn’t land a waitress job, she picked up her camera—a $20 Ica Reflex with a crack through the lens— and began taking pictures of waterfalls on campus. Her photos were reproduced in the Cornell Alumni News, and soon Bourke-White was approached by architects asking her to shoot pictures of their buildings.

Like her father, however, Bourke-White’s first love was machinery: “There is a power and vitality in industry which makes it a magnificent subject for photography.” Moving to Cleveland after graduation in 1927, she tried for months to get permission to photograph inside the steel mills, considered too dangerous for a woman. Finally, the head of Otis Steel relented, no doubt expecting Bourke-White to snap a few pictures and leave. Instead, she photographed all winter, climbing the sleet-drenched catwalks, getting so close to the molten steel that her skin burned and her camera blistered, coping with the then rudimentary photographic equipment (“film and paper had little latitude, negative emulsions were slow, there were no flashbulbs, no strobes”) until, despite the enormous scale of the mills and the extremes of light and dark, she got just the photos she wanted.

“HAVE JUST SEEN YOUR STEEL PHOTOGRAPHS. CAN YOU COME TO NEW YORK WITHIN WEEK AT OUR EXPENSE.—HENRY R. LUCE, TIME.” When the telegram arrived in 1929, Bourke-White had never heard of Luce and had no desire to photograph politicians for the fledgling news magazine. “All over America were railroads, docks, mines, factories waiting to be photographed—waiting, I felt, for me,” she recalled. But she couldn’t turn down a free trip. So she flew to New York, only to discover that Luce was offering her a dream job: to become the first photographer for his new magazine, Fortune, which would use dramatic images, coupled with words, to capture the romance of industry.

Bourke-White shot Fortune’s first lead story, on the Chicago stockyards, and went on to take striking and majestic photographs of bridges and factories, plow blades and lumber mills that resonated with an America hopeful that industry could raise the country from the Depression. In the 1930s, she turned her sights to Russia, a nation determined to industrialize overnight under Stalin’s Five-Year Plan. No Western photographer had yet been permitted in the Communist country, but Bourke-White hounded the Soviet embassy in Berlin, using her industrial photos as her talking points, until at last she was given a visa. “Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open, and I wanted to be the first,” she wrote in her autobiography.

In New York, she set up shop in the then unfinished Chrysler Building, perching on its Art Deco gargoyles to take pictures of the city from 800 feet up. She paid rent by shooting advertisements for Eastern Airlines, Buick, Goodyear and others, bringing to commercial photography the same appreciation of form that marked her industrial photos. But a Fortune assignment to shoot the Dust Bowl in the great drought of 1934 proved a life-altering event.

“During the rapturous period when I was discovering the beauty of industrial shapes, people were only incidental to me,” she would write in Portrait of Myself. “But suddenly it was the people who counted….Here were faces engraved with the very paralysis of despair. These were faces I could not pass by.” Shortly thereafter, Bourke-White had a nightmare in which she was chased down by Buicks, and she vowed to get out of advertising. “I longed to see the real world…where things did not have to look convincing, they just had to be true.”

About this time, notes biographer Jonathan Silverman in For the World to See, Bourke-White “moved herself into the growing circle of artists of that period who became keen observers and vocal critics of American social conditions.” She became involved in the First American Artists Congress, which denounced fascism and promoted free artistic expression. (Ultimately, she was the subject of a 200-page FBI file, obtained by Silverman under the Freedom of Information Act, and attracted the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee.)

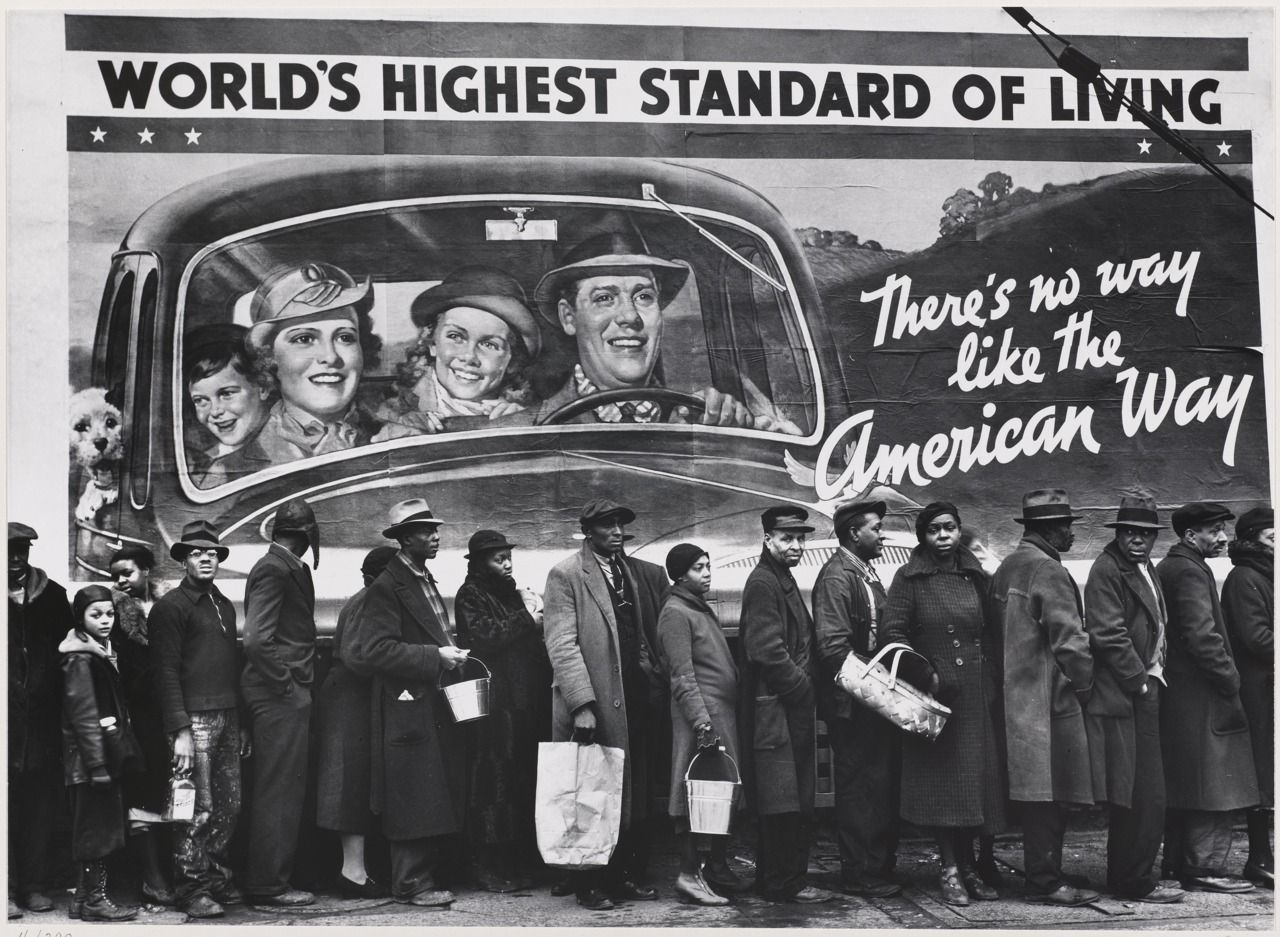

In 1936 Bourke-White met novelist Erskine Caldwell, author of the popular and scandalous Tobacco Road, and the two traveled through the South documenting the plight of poor sharecroppers. Bourke-White was moved by the sight of farmers’ shacks plastered for insulation with magazine ads for “bourgeois” products such as those she had shot not long ago. (The same sense of irony informed her classic 1937 photograph “Louisville Flood Victims,” which showed poor blacks huddled on a bread line beneath a billboard of a happy white family in their car and the banner: “World’s Highest Standard of Living”). Bourke-White’s collaboration with Caldwell resulted—in addition to a short marriage—in You Have Seen Their Faces, which combined text and photos to document the Depression several years before the publication of James Agee and Walker Evans’ book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Henry Luce helped usher in a golden age of photojournalism in 1936 with the launch of a magazine dedicated to interpreting the world through pictures. Bourke-White shot Life’s first cover, the Fort Peck Dam in Montana. Her accompanying photo essay—one of the first of its kind—showed the frontier life of dam workers. A photo of frontier families enjoying a night at the bar reflected Life’s commitment to depicting everyday America. “The media today would be interested in Montana on a Saturday night only if Ashton Kutcher and Demi Moore were there,” said William McKeen, chair of the journalism department at the University of Florida, Gainesville. “But at that time, they were interested in seeing real people doing real things. In the 1930s, photographers from Life and the Farm Security Administration began giving America a comprehensive self-portrait.”

Life’s circulation soon exploded into the millions. Its influence was enormous. It was a magazine ready to send a journalist anywhere in the world for the right picture, and Bourke-White was a photographer willing to go to any lengths to shoot it. During World War II, when Life’s photo editor had a hunch that Germany would break its nonaggression pact with the Soviets, Bourke-White rushed to Moscow. She photographed the bombing of Red Square from the roof of the American Embassy. Bourke-White was the first woman accredited as a war correspondent with the U.S. military. She sailed to the African front, where torpedoes downed her ship, and she found herself in a lifeboat on the Mediterranean (like Tallulah Bankhead’s character in Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat).

Undaunted, Bourke-White convinced the Air Force to let her become the first woman to fly on a bombing mission. On an air raid in Tunis, she flew in a B-17 piloted by Paul Tibbets, the quiet young man who would eventually drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima. “The camera is a remarkable instrument,” she wrote. “Saturate yourself with your subject and the camera will all but take you by the hand and point the way.” Bourke-White even asked Life to send her to the moon as soon as it was possible.

Her sense of social responsibility deepened with each trip. Riding with General George S. Patton’s Third Army into Germany, she photographed the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp, believing that as a war correspondent she had an obligation to bear witness to the atrocities. All too soon, she wrote, “The world would need reminders that men with hearts and hands and eyes very like our own had performed these horrors because of race prejudice and hatred.” Her outrage at racial injustice informed her photographs of Untouchable children in the leather tanneries of Madras (now Chennai), India, and South African gold miners toiling two miles under the earth in scorching and treacherous shafts.

By the time Bourke-White shot the violent partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, Henri Cartier-Bresson and a new breed of photographers were transforming journalism with their grittier, more candid photos. Still, the ever-resourceful Bourke-White managed to be the last journalist to interview Gandhi before he was assassinated. The former industrial photographer was deeply moved by the Mahatma, a man who eschewed industrialism—and the slavery he believed it would bring his people—in favor of the spinning wheel.

As Life lost its influence to television, Bourke-White lost her strength and vitality to Parkinson’s disease. She fought the disease with the same bravery and determination she brought to all her assignments. Eventually, however, Bourke-White, who had written or co-written a dozen books about her various adventures, lost her ability not only to shoot photos but also to type. In 1959 Life ran a photo essay on Bourke-White’s battle with Parkinson’s, shot by her longtime friend Alfred Eisenstaedt. After a lifetime behind the lens, Bourke-White was now the subject.

Bourke-White’s real legacy, according to biographer and photography critic Vicki Goldberg, “was to be a role model for women photographers. Many of these, even some whose work is nothing like hers, were spurred on by her example. Bourke-White proved that it was possible for a woman to break into what had been an almost exclusively male profession and end up at the top of the field.”

Margaret Bourke-White died in 1971.

Originally published in the February 2007 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.