Hell’s Kitchen was in trouble. The B-24 Liberator of the Eighth Air Force’s 44th Bomb Group had run into some exploding flak over Friedrichshafen, on the German side of Lake Constance, and was down to two engines, with gas gushing from the left wing tanks. The plane was 1,000 miles from its air base in East Anglia, with no chance of making it back. Dropping out of formation, Lieutenant George D. Telford told his crew he was going to try to land somewhere in neutral Switzerland.

As Hell’s Kitchen approached the Swiss border, 19-year-old flight engineer Daniel Culler, flying his 25th and final mission, spotted four Me-109s closing in on them. A small-town Indiana boy, Sergeant Culler was scared. His gun turret was not functioning properly, and he hated aerial combat. His widowed mother, a devout Quaker, had raised him as a pacifist. But after Pearl Harbor, Culler had decided that his duty to his country preceded his vow of nonviolence and, not yet 18, he persuaded his anguished mother to sign his enlistment papers.

As Culler and his fellow gunners prepared to open up on the fighters, Lieutenant Telford called out over the intercom that they had Swiss markings—two white crosses—on their sides. Swiss pilots were flying the German-built planes. One of them made radio contact with Hell’s Kitchen and ordered Telford to land the B-24 or they would shoot it down. It touched down at Dubendorf, just outside Zurich, and the crew exited, with Culler going last. He was about to jump from the plane when a strong hand grabbed hold of one of his feet and pulled him to the ground. “With a Swiss rifle pointed to my head and three soldiers holding me down, I looked around and saw Swiss guards with rifles pointed at all of us,” he recalled. “It didn’t look like a friendly place to me.”

His observation proved correct. Although officially neutral during the war, Switzerland was economically dependent on Germany and totally surrounded by Axis-controlled nations, a reality that colored the experiences of Culler and other downed American airmen there. On that day, March 18, 1944, 15 other American bombers landed safely or crash-landed in Switzerland. Culler saw several of these other bombers arrive in Dubendorf, and all of them, he later recalled, “were in bad shape.” Although he did not know it, Swiss pilots and anti-aircraft gunners had fired on some of them. That was not unusual. Over the course of the war, the Swiss would kill at least 20 Royal Air Force and 16 American airmen and injure a large number of others. In all, the Swiss attacked at least 21 of the 168 American bombers that intentionally landed in the country, even though most of them showed unmistakable signs of combat damage or distress.

By the end of the summer of 1944, more than 1,000 American fliers would be in Swiss hands, held under military guard and forbidden from leaving the country for the duration of the war. In the last two years of the war, the Swiss threw 187 American airmen into one of the most abhorrent prison compounds in Europe, a punishment camp run by a Nazi sympathizer. The story of these fliers is one of the darker secrets of World War II.

Within an hour after the Americans touched down in Switzerland, armed guards took Culler’s crew and the other American crews that landed at Dubendorf that afternoon to a large auditorium, where Swiss officials briefed them on the conditions of their confinement. They would be taken by train later that day, they were told, to a special camp in an isolated area in the center of the country where they would be quarantined for two weeks and then kept under guard for the remainder of the war. They would be granted liberties, but anyone leaving the confined area without permission would be hunted down and sent to a punishment camp. Swiss soldiers were under orders to fire at internees attempting to escape if they failed to heed a “Halt!” order. Since Switzerland was a nonbelligerent, the airmen were not considered either prisoners of war or evaders; having entered the country armed and willingly, they were classified as internees, even though they were treated like POWs.

Seeing an American general sitting on the stage next to Swiss officials in the auditorium at Dubendorf must have encouraged the captured airmen. But Brig. Gen. Barnwell Rhett Legge, a corpulent World War I cavalry officer who dressed in jodhpurs and knee-high leather riding boots, concluded the briefing with a stern warning. Men imprisoned for attempting to escape would have no appeal to either the American consulate or the American military attaché, Legge—the military attaché at the U.S. legation in Bern—told them; they would be under Swiss law.

Sergeant Culler’s crew was sent to the main American internment camp at Adelboden, a vacant summer resort 30 miles northeast of Lake Geneva. A single winding road led from the railroad depot at Frutigen to Adelboden. The camp commandant, a blond, blue-eyed officer who reminded Culler of every SS man he had seen in the movies, separated the officers from the enlisted men and assigned each group its quarters. The men were put up in stripped-down resort hotels, where they were kept under constant surveillance.

They were treated well, although conditions were far from ideal. The entire country was under strict rationing. Hot water, a luxury in wartime Switzerland, was turned on once every 10 days, and then for only a few hours. Without coal to heat their quarters in cold weather, the men ate their skimpy meals of black bread, potatoes and watery soup dressed in their flight suits and gloves. They ate meat only once a week and it was awful—usually blood sausage made from mountain goat.

The prevailing problem at Adelboden was boredom, and the prevailing sport was drinking, often to excess. The men could purchase their own alcohol with the small stipends they received in lieu of flight pay from the American legation in Bern, and some of them stayed drunk for days at a time. And after a while, boredom, spartan conditions, the growing proximity of Allied armies in France and what General Legge described as “the call to return to battle” fed the urge to flee.

The obstacles, however, were daunting. Some of the men took hikes deep into the mountains, escorted by armed guards who acted as guides. It was a storybook landscape: church bells chiming every hour, glacial lakes sparkling like giant jewels in the midday sun, but some men came back so depressed that they had to retire to their rooms. Only a crack mountain climber stood a chance of escaping through the massive Alpine peaks that rose, like so many imprisoning walls, around the deep, pine-scented valley. And beyond the impassable ranges, in every direction, lay the Reich. “Ever since that experience in Switzerland, I’ve been of two minds about mountains,” recalled airman Martin Andrews. “I find them beautiful, but also a little bit oppressive.”

The guards told Culler that those mountains he loathed prevented their country from being overrun by the German army. They also told him that more than 60 percent of the Swiss population was of German descent, and that many Swiss belonged to local Nazi groups and were not likely to assist an American on the run. Those were only half-truths. With its formidable Alpine front and an army of 435,000 troops organized into spirited local militias, Switzerland would have been difficult to conquer. But Adolf Hitler had no need to subdue this Alpine redoubt; he got most of what he wanted from the Swiss by a combination of intimidation and ideological symmetry.

Most Swiss citizens supported the Allied cause and opposed a Nazi takeover of their country. Yet there were at least 40 fascist and superpatriotic societies in the country, some with cells and chapters in more than 150 communities, most in the predominantly German-speaking cantons. With the active support of SS head Heinrich Himmler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, Berlin funneled money and ideas to many of those pro-Nazi organizations, all of which were aggressively anti-Semitic. The German legation in Bern openly supported a branch of the National Socialist German Workers Party, which boasted tens of thousands of committed followers. “Probably no other country in the whole of Europe,” wrote historian Alan Morris Schom, “was so thoroughly infested with similar groups in proportion to its population and geographic area.”

Most of those organizations drew their membership from the working and lower-middle classes, but the semisecret Swiss Fatherland Association was dominated by a powerful troika of political, business and military leaders who ruled wartime Switzerland. The leading members of the Fatherland Association were chiefly responsible for Switzerland’s strong economic ties with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Switzerland’s extreme economic vulnerability was at the root of this relationship: It depended on imports for almost all its fuel and much of its food.

Switzerland purchased coal and farm goods from Germany in return for steel. As a neutral, it had a legal right to trade with Germany and Italy, but international law forbade a neutral from supplying war goods almost exclusively to one belligerent nation. The Swiss contravened that decree. Walther Stampfli, a member of the Fatherland Association, organized Swiss industrial production to meet the needs of Hitler’s Germany. The leading Swiss banks—Nazi Germany’s bankers of choice— helped fund the Third Reich’s weapons production, and Swiss industries churned out essential products for the German war machine, including machine tools, aircraft cannons, radio parts, military trucks, freight cars, chemicals, dyes, industrial diamonds and ball bearings. The gigantic Oerlikon works, headed by Hitler-sympathizer Emil Buhrle, produced 120mm anti-aircraft cannons for the Luftwaffe, and other Oerlikon armaments were in the arsenal of nearly every Wehrmacht unit. The Swiss also built armaments factories inside Germany, some of which employed slave labor, under SS direction. Dr. Max Huber, the Swiss president of the International Red Cross, owned several of those plants in southern Germany.

Switzerland did take in some 200,000 refugees during the war, approximately 28,000 of them Jews, but the Jewish Swiss community and other organizations were charged a head tax to support them. And the Swiss turned down tens of thousands of Jews seeking refuge in their country; some were arrested and turned over to authorities in Germany and Vichy France.

In its defense, the wartime Swiss government explained to the Allied powers that it was the unwilling prisoner of geography. After the occupation of Vichy France in November 1942, Axis powers surrounded the country; the closest free nation was more than 1,000 miles away. Fearing reprisals or violations of its territorial integrity, the Swiss government permitted the Luftwaffe to set up a rest facility for its pilots at a fashionable hotel in Davos, a sylvan mountain resort. Distressed German fighter planes were also permitted to land at the same Swiss air bases that regularly fired on incoming Allied aircraft.

“You just wanted to land there and kiss Mother Earth and they’re shooting at you,” complained one American airman. But the bomber boy failed to realize that Swiss gunners had a reason to be vigilant, if often excessively so. Flying frequent and spectacularly large bombing missions close to the Swiss border, American bombers from both the Eighth Air Force and the Fifteenth Air Force, stationed in southern Italy, violated Swiss airspace hundreds of times—mostly accidentally—which angered Hermann Göring, from whom the Swiss had purchased much of their air force. On several occasions during the war, American bombers mistakenly attacked Swiss cities, among them Bern, Basel and Zurich. The worst accident occurred on April 1, 1944, when the city of Schaffhausen was devastated by 20 B-24s that had gotten lost in heavy cloud cover. Thinking they were over an enemy city, they unloaded their bombs on the market center, killing 40 civilians and injuring more than 100 more. The Swiss government demanded and received a formal apology and reparations, but this did little to assuage the anger of Swiss in the border communities.

The airmen interned at Adelboden suffered from the host country’s appeasement of Hitler and its rising impatience with Allied air incursions. If Switzerland had been truly neutral, those men and the men in the two additional camps set up for American fliers would have been accorded as many liberties as Allied internees were in another neutral country—Sweden— where many of them worked in the Swedish aircraft industry and were quartered in comfortable guesthouses. As it was, the Swiss army rarely mistreated the airmen who stayed in their camps and waited for the end of the war. But those daring to escape entered a heavily armed country where loyalties were mixed and where soldiers, police and court officials were ordered to be tough on captured American airmen.

Daniel Culler feared the unknown. Growing up in insular Syracuse, Ind., he had never wandered more than 30 miles from home. Yet now all he could think about was escaping into the unknown to “rejoin the fight against…oppression.” His patriotism was so ardent it seems, in retrospect, contrived. But in shedding his Quaker beliefs to kill for his country, he believed that he had given up any chance of entering heaven. His only hope for the hereafter was that God had created a special place, short of heaven but far from hell, for those who committed licensed murder for a clean cause.

The first time Culler escaped, in May 1944, he and two companions got lost and nearly died of exposure in the mountain forests along the Italian border. In excruciating pain from the bleeding scabs on his feet, and so sick from accidentally eating poisoned berries that he could barely walk, Culler returned by himself to Adelboden.

After reporting to the commandant of Adelboden, Dan Culler was sentenced to 10 days’ solitary confinement in the Frutigen jail. His companions, he learned later, were caught by Swiss border guards and imprisoned. After serving his sentence, Culler was taken to a high-security punishment prison called Straflager Wauwilermoos or, in English, “prison camp at the swamp of Wauwil,” a village near Lucerne. Culler was never told why he was sent there, or for how long. As he passed through the gates of the prison, his military guard whispered to him: “I’m sorry to bring you to this hellhole. Watch your every step. There are some awful men in here, and you are so young.”

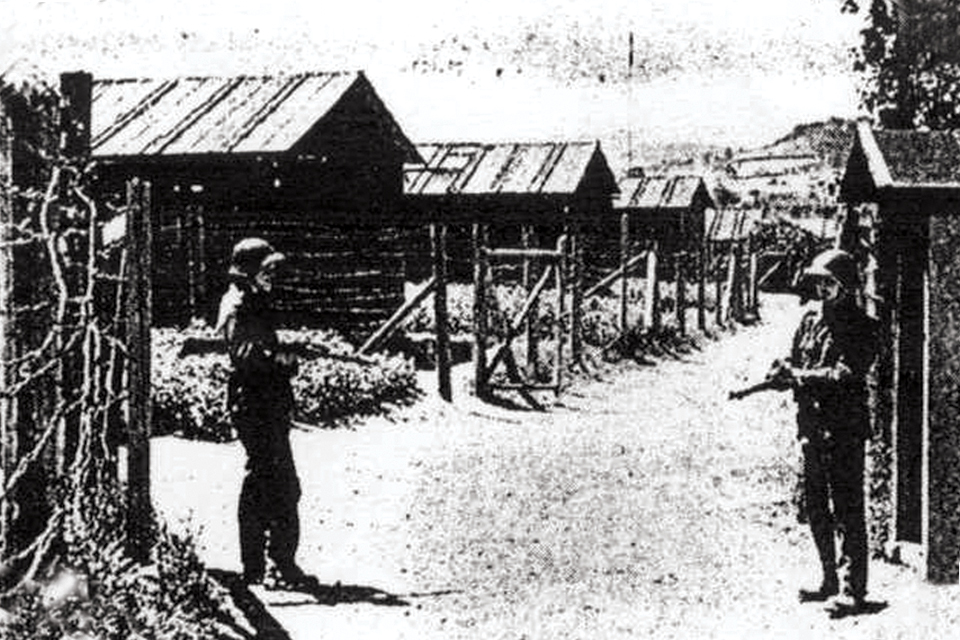

Wauwilermoos was a close-packed compound of mud-splattered barracks surrounded by a high barbed wire fence and patrolled by guards with machine guns and attack dogs. Built in 1941, it was a disciplinary camp for lawbreakers and escapees among Switzerland’s ballooning population of military internees from nearly a dozen countries. To run it, Swiss authorities could not have chosen a more odious character. Captain André-Henri Beguin, a former officer in the French Foreign Legion, was as corrupt as he was cruel. At the time, he was under investigation by Swiss authorities for adultery, bribery, embezzlement of prison funds, spying for the Germans and unlawfully wearing a Nazi uniform (while living in Germany before the war, he signed his correspondence “Heil Hitler”). The officers he appointed were as coarse and corrupt as he was. They treated us “like scum,” said Eighth Air Force bombardier James Misuraca. “The Swiss called this a punishment camp, but it was more like a concentration camp.”

When guards shoved Culler through the door of Barrack Nine he nearly passed out from the stench. Every Indiana barn he had ever been in smelled better than this place. The wooden floor was covered with filthy straw, which the prisoners slept on and used for toilet paper after they evacuated in the miasmic slit trench just outside the front door. “What happened to me that night, and many more to follow, was the worst hell any person ever had to endure,”

Culler wrote in his searing prison memoir. A group of Russian prisoners held him down, stuffed straw in his mouth and sodomized him repeatedly. “Coming from a small farming community, I never heard of men doing to me what they did. I…hadn’t even been with a girl, except to hold her hand and give her a light kiss on her cheek or mouth. I was bleeding from all the openings of my body, and I prayed to God to take my life from me.”

He was raped again the next morning and forced to have oral sex with several of his assailants, who stuck sticks in his mouth to pry it open. After being knocked unconscious, he awoke to find blood running down his throat. Too weak to move, and with his hands tied behind his back, he was thrown into the waste ditch outside the barracks. “When I finally came to my senses, I crawled from the ditch and tried to wipe myself with straw. I noticed something was hanging from my rectum, and realizing it was skin from the inside, I tried to push it back in.”

A few hours later, Culler staggered into Beguin’s office, screaming uncontrollably. “They all stared at me as though I [was] some kind of freak, and a sort of nasty grin came across their faces.” For the first time in his life, this son of a Quaker minister found himself cursing at another human being. But no one understood him; no one spoke English. Tiring of Culler, André Beguin stood up and pointed toward the door with the riding crop he always carried. His guards promptly tossed Culler out the door.

Within days Culler’s entire body was covered with boils from the lice and rats in the feces-contaminated straw. The rapes continued and became more violent. He began to vomit blood and an unknown yellow substance, and he developed chronic, bloody diarrhea.

When a British sergeant major visited the camp to check on the English prisoners, Culler asked him why the Red Cross had not come to inspect this place, why he was being held without trial and why had the American military attaché in Bern, General Legge, not been informed of his imprisonment. On a later visit, the sergeant major told Culler that he had intervened on the American’s behalf to the British authorities in Bern—but had been told that Legge refused to believe that the Swiss had a place like Wauwilermoos, and that Legge’s official position was that if an American airman tried to escape, he should be subject to Swiss punishment.

When Culler was finally taken from Wauwilermoos and given his day in court, he discovered that Swiss justice was a mockery. The military court proceeding was conducted entirely in German, and when it was over, Culler was handed an English translation of the transcript. He would be sent back to Wauwilermoos without medical treatment and for an unstated period of time. The transcript did not contain a single word of his oral testimony describing his rape and the conditions inside the prison. The final indignity was a bill Culler received for 18 francs—compensation for the court’s time and trouble.

Back in prison, Culler was tormented by a loud ringing in his ears—the result of the beatings he’d suffered at the hands of the Russians. They had been transferred, but sitting alone in a corner of the barracks, wrapped in a thin blanket, Dan Culler felt he was losing his mind. “The last I remember at Wauwilermoos, I was acting like a madman, trying to stuff straw down my throat so I could not breathe.” As he began to lose consciousness, he heard the British sergeant major shouting orders at two Swiss guards who were trying to revive him. “After that everything went black.”

Later, the sergeant major told Culler that the British government in Bern, at his insistence, had gotten a Swiss diplomatic official to sign a paper demanding that he receive immediate medical treatment. Culler woke up in a Swiss military hospital, and after a few days he was transferred to a tuberculosis sanitarium in Davos, near the Austrian border.

From there he escaped to France on September 26, 1944, the way paved for him by his pilot. With the help of Air Forces personnel stationed at the Swiss consulate, Lieutenant Telford paid some Swiss operatives to orchestrate his entire crew’s escape and hand them over to members of the French Resistance. As they crossed the border on foot, Swiss guards opened fire on them, wounding Telford in the ankle. An Eighth Air Force C-47 cargo plane then flew the crew to London with a group of other internees—British and American—who had recently made it over the border.

Lieutenant General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, had arranged for the airlift. In August 1944, Spaatz had begun urging Washington to pressure the Swiss to release interned Air Forces personnel. He also sent word into Switzerland that airmen would be held to their oath to escape captivity. At this point, American Air Forces officers serving in diplomatic positions in Switzerland, as well as members of the U.S. consulate in Zurich, began defying General Legge’s orders and actively helping airmen escape. At the instigation of Secretary of State Cordell Hull, the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, established an underground network; fliers were hidden in the American legation in Bern and then sent to the border in boxcars or ferried across Lake Geneva.

Sam Woods, a former Marine pilot who was the American consul general in Zurich, set up an escape network on his own that helped more than 200 internees reach France. Clandestinely meeting dozens of them in churches and cemeteries, he provided them with false passports and drove many of them to the frontier in his black sedan. At the border, Woods would enter a Swiss tavern that was connected to a French pub by an underground sewer line equipped with a telephone hookup. Woods used the phone to alert his French compatriots that a group of Americans was ready to come over. Running this freedom line took money, a lot of it for bribes, but Woods had a steady supply of funds, courtesy of Thomas J. Watson, the founder and president of IBM, who channeled cash to Woods through his company’s European office.

As the ground war came closer to Switzerland, increasing numbers of airmen sought out General Sam—as the fliers he spirited to freedom had anointed him. The internees’ chances of successful escape had greatly improved now that the German army had been driven from France and the American Seventh Army, which landed in southern France on August 18, 1944, reached the Swiss border near Geneva.

When France was liberated, the Axis encirclement of Switzerland was broken. With friendly air bases everywhere in France, the attractiveness of landing in Switzerland diminished. During the last three months of 1944, only five American heavy bombers landed in Switzerland. All were from the Fifteenth Air Force—battle-ravaged planes that had no chance of returning over the intimidating Alps to southern Italy.

In London, Army intelligence and OSS agents put Dan Culler through an exhaustive round of interrogations. No one believed his grisly story about Wauwilermoos. “Sergeant, you are a goddamn liar!” he was told at one point. “There is no such place as Wauwilermoos…and if there was, the Swiss would not put any American soldier in there for nothing more than an attempted escape.” In desperation, Culler stripped off his shirt and shoes to reveal the boils all over his body.

Those men, Culler realized, did not want to believe his story. At the time, American diplomats were negotiating a reparations payment to the Swiss government for the accidental bombing of Swiss cities, and General Legge was still trying to close a deal with the Swiss for the repatriation of the 600 or so remaining American internees. The U.S. government wanted no negative publicity about the Swiss while those negotiations were in process. If Culler went public with his story, the Army, he was told, would declare him mentally incompetent and put him in a mental detention hospital for years.

After swearing to remain silent about his captivity, standard procedure for both internees and evaders, Daniel Culler was shipped home in November 1944. When he walked into his mother’s kitchen and she saw his condition, the first words out of her mouth were, “I warned you about those awful wars!”

Donald L. Miller is the John Henry MacCracken Professor of History at Lafayette College in Easton, Pa. He is the author of prize-winning books on American history; Masters of the Air was named one of World War II Magazine’s best books of 2006.

Originally published in the April 2007 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.