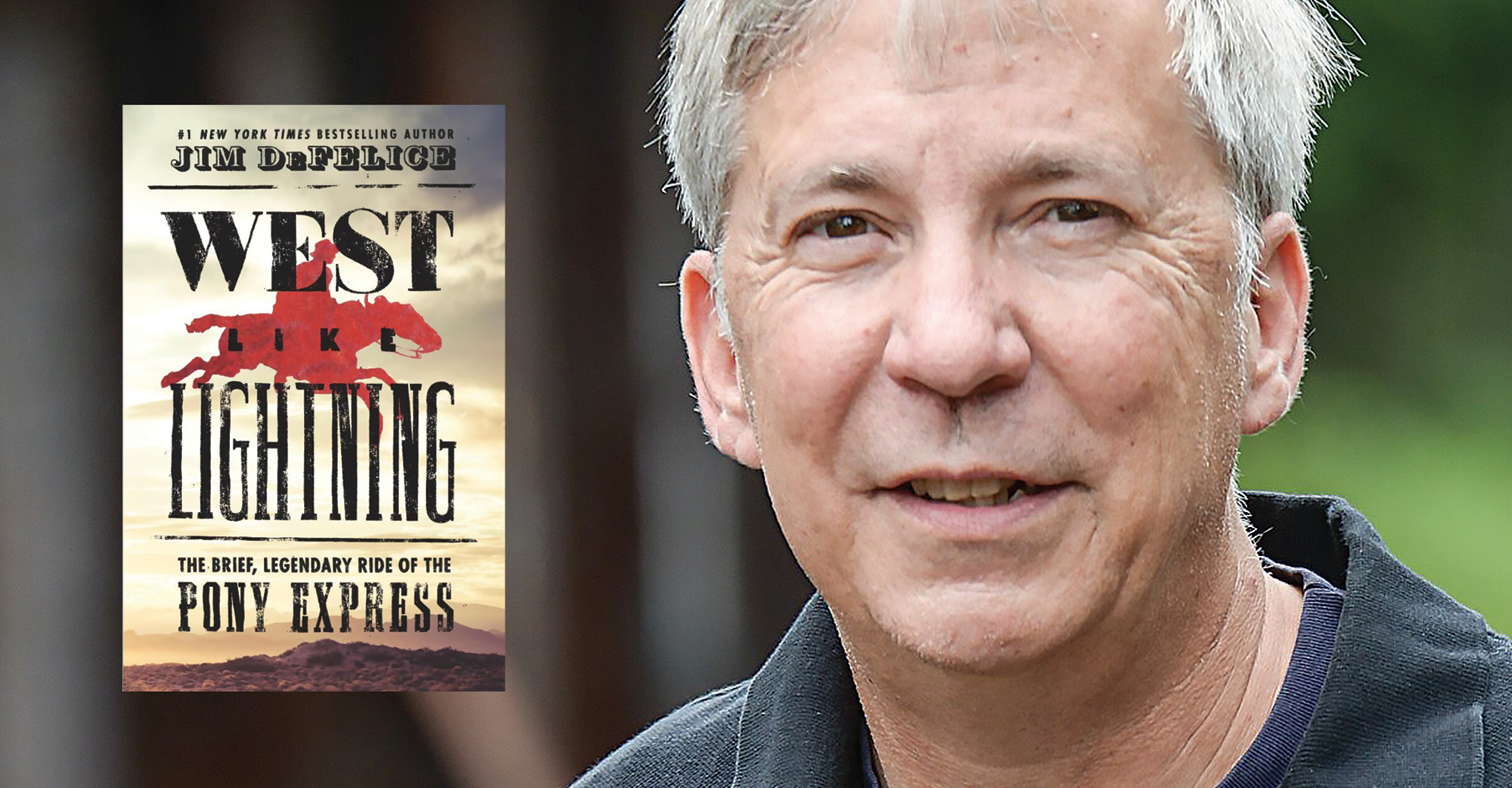

Jim DeFelice is best known for writing about such American military heroes as General of the Army Omar Bradley (Omar Bradley: General at War) and Navy SEAL Chris Kyle (American Sniper), and he’s working on a memoir with Ray Lambert, a 98-year-old Army medic who landed with the first wave of American soldiers at Omaha Beach on D-Day in 1944. DeFelice moved away from modern warfare and into the 19th century, however, to chronicle one of the American West’s enduring legends in West Like Lightning: The Brief, Legendary Ride of the Pony Express, which Western Writers of America recognized as a 2019 Spur Award finalist for best historical nonfiction book. DeFelice recently spoke about the project from his home near the New York–New Jersey border.

Jim DeFelice is best known for writing about such American military heroes as General of the Army Omar Bradley (Omar Bradley: General at War) and Navy SEAL Chris Kyle (American Sniper), and he’s working on a memoir with Ray Lambert, a 98-year-old Army medic who landed with the first wave of American soldiers at Omaha Beach on D-Day in 1944. DeFelice moved away from modern warfare and into the 19th century, however, to chronicle one of the American West’s enduring legends in West Like Lightning: The Brief, Legendary Ride of the Pony Express, which Western Writers of America recognized as a 2019 Spur Award finalist for best historical nonfiction book. DeFelice recently spoke about the project from his home near the New York–New Jersey border.

When did you first learn of the Pony Express?

I’ve heard stories about the Old West since I was old enough to hear stories.

What drew you to write about it?

I have a personal project—or maybe just ambition—to trace American history through different decades/periods using different events, people, etc., and the Pony fit right in. But it was really my editor at William Morrow, Peter Hubbard, who suggested doing something on the Pony Express. The service touched so many different aspects of American life, then and now, that it was perfect for that larger purpose. And of course there are so many great stories and characters attached to it that it’s a natural subject.

How did your research toward it compare to American Sniper or Omar Bradley?

The differences are obvious—the periods of all three, for example. And of course working with Chris was a pretty intense thing, where we spent a lot of time together over a period of months and years. There were no Pony Express riders to interview—though I would have loved to have hung out with [Pony Express entrepreneurs William] Russell, [Alexander] Majors and [William B.] Waddell. But at heart all three books involve situations where the protagonists are up against incredible odds, whether testing themselves in battle or against nature. I had to do a lot of research, with primary and good secondary sources for all—even memoirs require going through records, etc. And all represented opportunities to place the subjects in their specific time and place.

Given the few extant records, how difficult was it to separate fact from fiction?

Separating fact from fiction is always difficult, especially when you’re talking about the Old West. In writing the book, I didn’t want to lose the fiction—legend is a better word—because in many cases it tells us as much about who we were and who we are than the actual facts. I love the stories connected with the Pony and beyond, and not just because they’re entertaining.

On the other hand, I did have a responsibility to delineate the truth. The work the Settles [Raymond W. and Mary Lund Settle, authors of Saddles & Spurs: The Pony Express Saga and War Drums and Wagon Wheels: The Story of Russell, Majors and Waddell] did really is the foundation, and there have been many others. There are some intact records, of course, but not anywhere near what we’d love—like a complete set of financial books for the companies, if those were ever kept. Other things—newspaper articles from the time, census records, congressional testimony—all of that can be mined.

There are definitely places where it’s just impossible to know with 100 percent certainty the facts—like who exactly was the first rider out of St. Joseph. Sifting through the possibilities is part of the process and really part of the fun. It’s always interesting to read a new theory or hear a good argument about something that’s been overlooked.

One thing I realized working on this book: Writers working on popular history have a lot easier access these days not only to the “deep dives” historians and scholars make, but also to the tools they use. To give a very simple example: It was relatively easy to access census records, to see if they might be useful. In the past only a specialist would have access and time to do that.

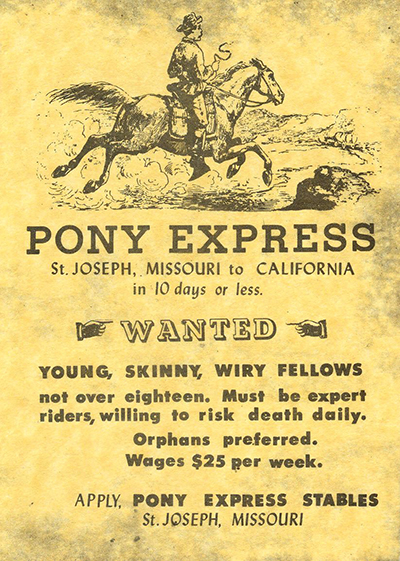

So, who might have been the first westbound Pony Express rider?

I was at an event in Marysville, Kan., and one guy got really, really worked up about whether Johnny Fry was the first, as has been refuted—which I call into question in the book. I thought it was really good that people get passionate about history. But the truth is we don’t really know who the first person was. We don’t know the identity of a lot of riders for bunches of reasons, one of which is that a lot of the records—if they were even keeping records—of the Pony Express companies were lost or burned, purposely or otherwise.

What did you discover regarding the eastbound journey?

In a lot of ways, moving information from west to east was more important than going the other way. Here’s the weird thing—to me, anyway. In looking at the statistics, it always took an extra day more to go from west to east than it did to go from east to west, and I don’t understand. My first thought was maybe the bars were better as you come from the west, and you’d just hang out a little more. But presumably they’re the same places, so I don’t know, but it’s fascinating.

You drove and hiked much of the route. How did that play into your writing about the Pony Express?

The first thing it did was remind me how beautiful this country is. It helped me understand what a monumental physical achievement [the Pony Express] was. The vast distance and the geography were major impediments, but also simple facts of life. The relationship of time and distance was obviously different then, but how much different isn’t readily apparent until you’re walking a few miles between stations—which obviously the riders wanted never to have to do.

Actually going across the trail (which is very doable, thanks largely to the National Park Service and its maps, as well as the National Pony Express Association) was the opportunity to meet a lot of the people—local historians, museum staff, etc.—responsible for keeping the memory alive. I also feel somehow more connected to a subject by seeing where it was or is physically.

‘I love just wandering around and getting lost and occasionally going somewhere I shouldn’t’

Did any particular place along the route stand out?

They’re all so cool. I love just wandering around and getting lost and occasionally going somewhere I shouldn’t. But what really stood out were the people. So many people are into history and so willing to give me their time. That’s what I really remember.

How important was Buffalo Bill Cody to the history of the enterprise?

Aside from Russell, et al., Buffalo Bill was probably the single most important man in the Pony’s history. Not as a rider—he almost certainly didn’t ride—but because he featured the Pony in his Wild West shows. If he hadn’t done that, it’s very likely we would barely know about it—just as we barely know about the many other, shorter express services of the time and earlier. He helped popularize it, rekindling the Pony’s legend.

Why did Russell, Majors and Waddell even launch this inherently shaky venture?

The service was intended as something of a loss leader to land a major government mail contract. It was also part of a larger ambition to create a financial empire built on transporting information and goods throughout the West. The Pony itself was never intended as being a moneymaker, nor anything other than short-lived. It got plenty of publicity, extended their transportation network, helped with some real estate transactions. They got a sweetheart deal from St. Joe’s. In those senses, it was certainly a success.

Historians have tended to look at the few numbers available related to the cost of the service and say, “It was a foolish venture—it cost far more than it could ever bring in.” The parent company (or conglomeration of companies) were clearly in trouble beforehand, and expenditures from the Pony probably helped hasten their demise. Although, perhaps the service extended their life a few months, both because of the contract and the leverage Russell got with creditors. In any event, the real question of whether it was a sound business venture really has to be directed at the overall concept and aim. You can certainly fault Russell, Majors and Waddell for their execution and business plan; on the other hand, American Express and Wells Fargo had similar visions and histories (different business approaches, though).

‘Saying you rode for the Pony would probably get you a beer or at least a pat on the back; saying you held the horse while the rider hopped on would probably elicit a weak smile’

Who were some of the service’s unsung heroes?

My favorite Pony character—I don’t think I can actually call him a hero—is Jack Slade. Any character that was celebrated by Mark Twain may not be unsung, but most of the general public doesn’t know him. The real unsung heroes are the stationmasters and the kids who waited in all sorts of weather to change the horses, especially in Nevada Territory. You can pick up some good stories about them here and there, but for the most part they’re utterly lost to history. They didn’t even have bragging rights back in the day. Saying you rode for the Pony would probably get you a beer or at least a pat on the back; saying you held the horse while the rider hopped on would probably elicit a weak smile.

What factor did the telegraph play in the Pony’s fate?

To get a little technical, there are really two periods of the Pony—the time under Russell, Majors and Waddell, and the time under Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo took over the route intent on killing it; they kept it going until the telegraph line from the East reached the West, but at least in my opinion that was more a convenient mark rather than a nail in the coffin (though it made a good PR story, intentional or not).

In the Russell, et al., period—which really is the Pony we all know, or think we know, and love—the telegraph was at times incorporated into the service. It was used to speed the delivery of Abraham Lincoln’s election, for example. From the service’s point of view, the telegraph would have most effectively replaced the news dispatches that newspapers got; forgetting the minimal revenue, the real value there was the mention of the “Pony” and its prominence in stories that were always on the front page, even back East in New York City, for example, which greatly enhanced the value of the parent companies.

But the telegraph line wasn’t anywhere near complete across the country when the operation tanked. It was the overall weight of the empire, the screwed up federal contracts and Russell’s chicanery that killed it.

One interesting question to me is, if Russell and his partners had succeeded with their grand plan, what would they have done with the service? The telegraph lines would take away some of the mail, but far from all—there’s still be a need for actual letters dispatched quickly. The railroads would be a far bigger threat. But given that they too had also been integrated into the Pony service from the start, I would guess the companies would have offered something even faster using the train, and maybe still calling it the Pony Express, since they’d had such success with branding.

Why is the Pony important?

It’s a story of man versus nature, of the relationship between time and distance, and of our need for speed. It’s also become attached to a lot of legends that tell us who we are. And it’s entertaining, which is what history should be. You can’t learn from it if you don’t listen to or read it, and the Pony is filled with stories that are entertaining, and you do want to listen.

I hope the book is a gateway to more and deeper history about the period and our country in general.

Why are big publishing houses showing renewed interest in the American West?

First of all, it’s the West. How can you go wrong with so much cool stuff going on? The great thing about the Pony Express is that it touches so many different aspects of American history; this was going on when Lincoln was being elected. The great thing about writing about the West is there’s an entertaining factor, and if I can entertain people, that’s my goal.

What are you working on now?

I’ve just finished working with one of the last surviving GIs who participated in the first wave of landings at Omaha Beach on D-Day. He was a medic and over the course of his career must have saved thousands of lives. His name is Ray Lambert, and he’s still going strong at 98. The book is called Every Man a Hero, and I’m in total awe of him. WW