The Poll Giant would have been World War I’s biggest bomber—had it actually been completed.

It’s one of the most enigmatic objects in Britain’s Imperial War Museum—a gigantic 8-foot plywood landing gear wheel, all that’s left of what would have been World War I’s largest airplane. Recent research has questioned much of what we thought we knew about the purpose of this extraordinary machine, what happened to it, and the character and reputation of its designer.

The Poll Giant was a monster. Huge sections of the unfinished airplane were discovered by a team of Allied military inspectors in a hangar at Westhoven, near Poll, Germany, in 1919. Their report revealed mind-boggling dimensions: The 10-engine triplane would have been nearly five stories tall, with a wingspan greater than a B-29’s. The fuselage and wings were all sheathed in three-ply wood, prompting the inspectors to comment on the good workmanship but seemingly heavy and weak design. Identifying the designer simply as “Forstmann,” the inspectors said the airplane’s endurance was planned to be 80 hours at a cruising speed of 80 mph. The report offered a single tantalizing statement about why the Poll was built: “Function—heavy bombing, long distance machine, alleged to have been intended to bomb New York. No trace of any gear or bomb release gear found.”

More clues emerged in The German Giants, the landmark 1962 study of Germany’s massive multi-engine Riesenflugzeuge, or R-planes, authored by George Haddow and Peter Grosz. Digging into the German navy archives, they found a document revealing that the triplane was a project of the Brüning company, a leading plywood producer, which was asking the navy for support. Its designer was Swedish engineer Villehad Forssman, who as early as 1914 had conceived one of Germany’s first multi-engine bombers while working for Siemens-Schuckert Werke. Haddow and Grosz depict this pioneering craft, the SSW-Forssman, as a lumbering, expensive disaster, plagued by incompetent design choices and weak construction. Over a year of testing, it crashed so often that pilots refused to fly it. It was finally delivered to the Idflieg (military aviation bureau) in early April 1916, but a week earlier SSW had ignominiously fired Forssman.

Despite his unpromising track record, the Brüning company hired Forssman as its chief designer, and he dreamed up the monster triplane. Haddow and Grosz dismiss the project as another example of the Swede’s “naiveté,” and the proposal to bomb New York “as entirely in keeping with Forssman’s creative fantasy.” This damning verdict held fast in aviation history circles for more than four decades.

Then in 2009 aviation historian Günther Sollinger published an exhaustive biography of Forssman suggesting a very different picture. In the Siemens archive, Sollinger found evidence of a simmering feud between Forssman and two other designers on the staff, Bruno and Franz Steffen. At the same time Forssman’s early bomber was being tested, the Steffen brothers were developing a rival multi-engine bomber at SSW. Sollinger believes that the Steffens, popular ex-pilots who had served at the front, used their military connections to promote their own design and marginalize Forssman within the company. He thinks Haddow and Grosz were unduly influenced by a scathing unpublished account about Forssman that Bruno Steffen wrote in 1950. And Sollinger argues that rather than a sign of incompetence, the SSW-Forssman’s teething troubles were typical of an era when designers were struggling to figure out how to build the first generation of multi-engine airplanes. The Steffens themselves took more than a year to develop their bomber, with numerous setbacks.

If our view of Forssman has been biased, what about his giant triplane? Sollinger’s dig into the archives unearthed conflicting accounts. In one navy document, the project is said to have originated as a civilian airliner for crossing the Atlantic—highly unlikely, given the wartime setting and the fact that the navy had loaned Brüning engines. A more credible report was written by the Swedish naval attaché in Berlin, who met with Forssman in the summer of 1917. During their talk, Forssman said that Brüning was constructing a number of the machines as heavy bombers for the navy to attack Paris and British cities from Germany. Fully loaded with 20 tons of bombs, the 75-ton triplane would have been able to reach as far as northern Scotland and return in about 13 hours. A veritable flying fortress, it was to be massively armed with a forest of machine guns and two cannons on the top wing. If Forssman was exaggerating to impress his Swedish contact, he certainly succeeded: The attaché wrote that “compared to this giant the latest army airplanes used in the attacks against London are merely toys.”

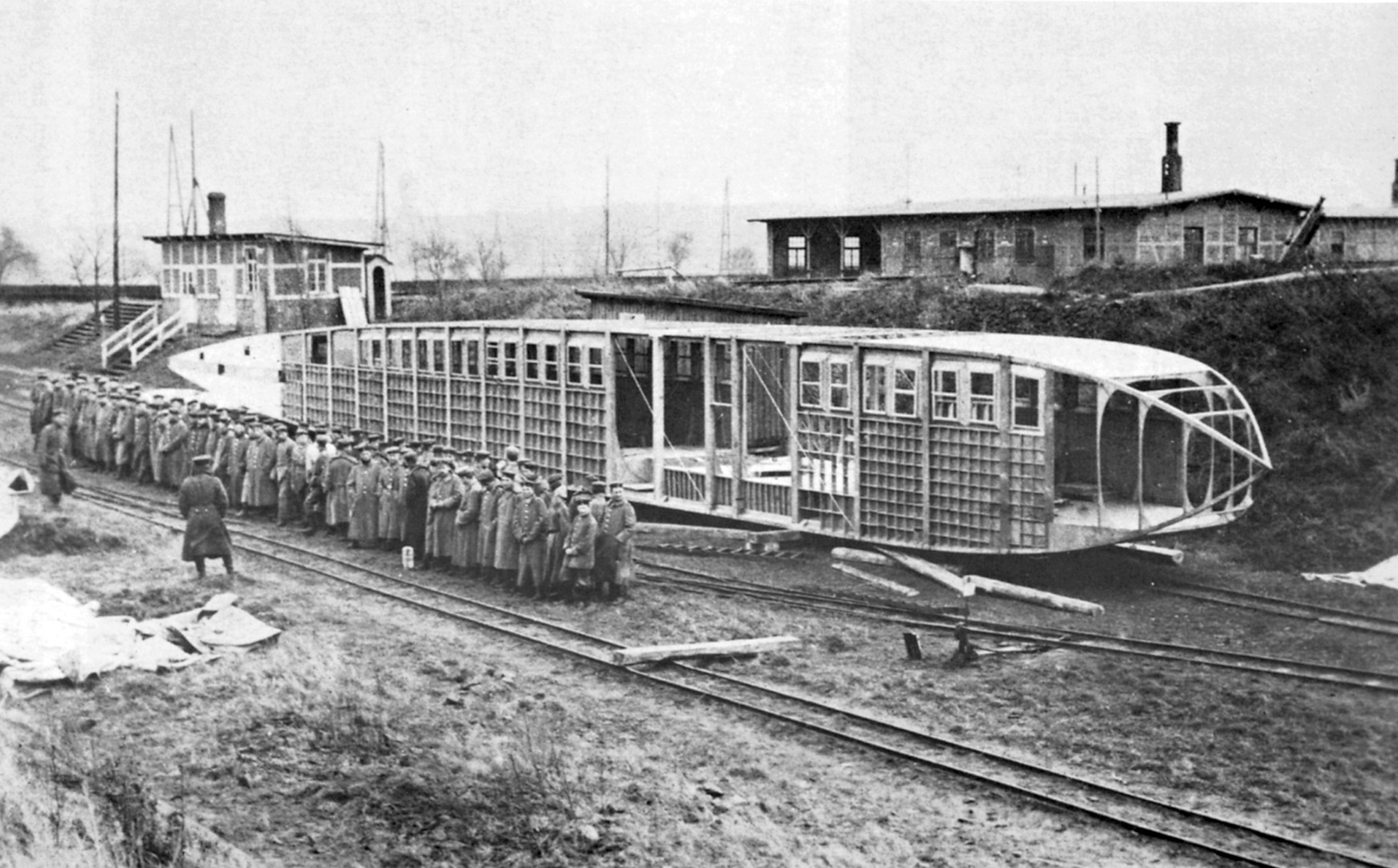

In the fall of 1917, the navy was ordered to stop developing R-planes and finally declined Brüning’s request for financial support. Instead a new commercial backer, industrialist Reinhard Mannesmann, took over the project. To accomplish the transfer, giant sections of the triplane were moved from Brüning’s facility at Kahl to Mannesmann’s specially built hangar at Westhoven, some 150 miles away, via narrow-gauge railroad and river barge down the Rhine. This herculean feat was captured in a memorable series of photos, our best visual record of the unfinished megabomber. They show a team of 30 to 40 soldiers manhandling the enormous plywood fuselage and wing sections across the wintry landscape, using wooden rollers and levers to load them onto the railroad car and barge. It’s aviation’s equivalent of Cecil B. DeMille’s scene of slaves hauling pyramid blocks in The Ten Commandments.

After that daunting move, the trail runs cold. A military visitor to the Westhoven hangar in 1918 said he was “impressed by the clean workmanship” and “the very handsome engine nacelles…intended for a tractor and pusher engine each.” No record exists of why the triplane was still unfinished when Allied inspectors discovered it there in September 1919. But the R-plane program as a whole had proved disappointing. The 30 or so giant bombers that reached the front were costly and difficult to operate, and failed to make an impact on the air war or enemy morale. Those factors must have militated against completing a machine that dwarfed even such massive R-planes as the Staaken R.VI (see “Extremes,” September 2014).

But was the Poll triplane the white elephant it has been portrayed as? And was its designer a fantasist or an innovator ahead of his time? Sollinger argues that both the German navy and Idflieg must have approved the diversion of considerable resources, if not direct financial support, to the project. “Is it reasonable to assume,” he asks, “that Idflieg would allow Brüning, later Mannesmann, to engage in this extraordinary venture if they felt it was useless?” In the end, the Poll Giant saga leaves us with more questions than answers, and a single tangible relic—that finely crafted yet seemingly impractical wooden wheel in the IWM.

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!