Józef Haller dreamed of an army that would help bring about the return of an independent Poland.

The battle began unexpectedly, in the middle of the night, on May 11, 1918. Polish general Józef Haller had one day to live.

was captured or killed. (National Digital Archives)

Haller’s Polish II Corps had spent the past few weeks fighting the Germans in small skirmishes more typical of guerrilla warfare. Ever since Russia’s withdrawal from World War I a few months earlier, Haller’s ragtag force of Poles had been acting as a rogue unit. Polish units such as the one he commanded had been conscripted into Russian or Austrian forces and were biding their time until they could fight for a unified Poland. Most didn’t survive long; they were usually disbanded, assimilated into the Russian White Army fighting the Bolshevik revolutionaries, or defeated by stronger German forces.

The 44-year-old Haller, an experienced officer and a graduate of Vienna’s Technical Military Academy, was determined to save his troops from those fates. He had moved his soldiers to Kaniv, Ukraine, a week earlier, seeking a respite from the fighting in the Carpathian Mountains. On May 6 the German High Command had ordered the Poles to surrender. Haller was not ready to oblige. On the night of May 11–12, he and his men awoke to artillery fire raining down on their position. Within minutes, it was apparent to Haller that his 8,000 troops were surrounded.

Haller reacted swiftly, ordering his men to take up defensive positions on the highest peaks encircling the nearby village of Yemchykha. The Germans attacked them relentlessly. For General Franz Hermann Zierold, the German commander, the battle was personal. Just a few months earlier, Haller had betrayed Austria, his country of birth and Germany’s ally, by sneaking his unit across its border into Russia. Haller was instantly infamous.

As night turned into day and back to night, Haller worried about his soldiers’ lack of ammunition and supplies. He knew that the Germans wouldn’t stop until he was captured or killed. As he dispatched a runner to accept the German offer to negotiate the terms of surrender, Haller looked long and hard at the officers in front of him and sighed. He thought of the first verse of the Polish national anthem: “Poland has not yet perished / So long as we still live.” And then he decided to die.

When the Germans accepted the surrender delivered by Haller’s second in command the next morning, they were notified that the general had been lost in battle. His body, which apart from the uniform and insignia was too badly mangled to be recognized, was shown to the initially skeptical German officers. As impossible as it seemed, it had to be true. The II Corps, they reasoned, would never have surrendered if Haller were alive.

The real Haller, masquerading as a sweaty and dirty “Józef Mazowiecki,” linked up with hundreds of other Polish military refugees from the front and made his way through the dense forests northward to Moscow. His aim was to contact the Polish Army Commission, which had been created under the tsar to champion the Polish cause. Haller hoped the commissioners would help smuggle him from Eastern Europe into France.

In his pocket, Haller clutched the transcript of a June 4 decree from French president Raymond Poincaré. The French government had not only accepted Polish Legions into service but had also sanctioned the creation of a free Polish army, the first since General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski’s legions had fought for Napoleon Bonaparte a century earlier. Haller intended to command this army, even if he had to become someone else in order to do so.

Coming from a family of landed gentry, Haller had gravitated toward the military from an early age, attending military schools in Hungary, Moravia, and Austria before spending 15 years as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. After leaving the service with the rank of captain in the 11th Artillery Regiment, he helped train Polish scouts in a secret soldier society known as the Falcons.

When World War I broke out in 1914, it held no great promise for the fate of the forgotten nation of Poland or its people. At the height of its power, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth controlled a vast empire that encompassed present-day Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, and western Ukraine. By 1795 and its fateful last partition, however, Poland was no longer a real nation-state. In fact, because they were so geographically divided, Poles began World War I fighting for the Allies in the Russian and French armies as well as for the Central Powers in the Austro-Hungarian and German armies. But Haller, the man who would eventually command the first independently recognized Polish army in more than a century, had at that time quit the military life altogether and was back home tending to his family farm in Lviv.

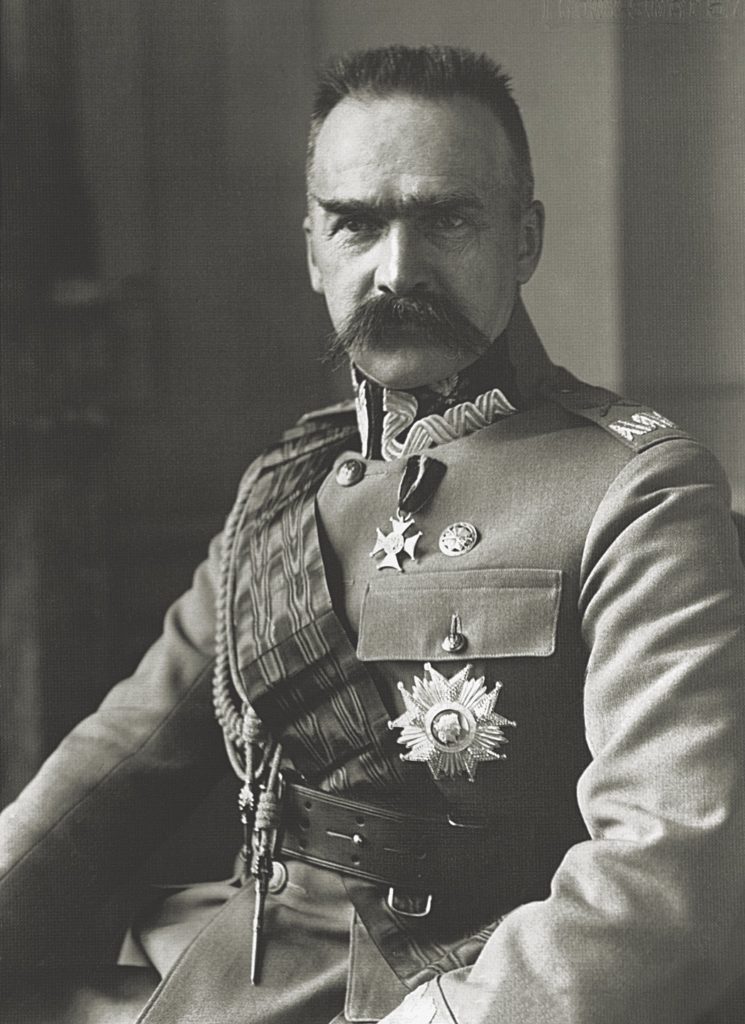

Haller’s story was not much different from that of General Ulysses S. Grant, the celebrated American commander whose eventual military glory contrasted sharply with his prewar obscurity. Haller, like Grant, had been brought out of quasiretirement. Haller resumed command as a colonel in the Austrian army in the summer of 1914. Around this time, Józef Piłsudski, the eventual commander in chief of Poland’s postwar armed forces, said that Haller had a “weak military background and lackluster leadership abilities” as well as a “sometimes illogical military mind” and was scarcely fit to command a squadron, much less lead a Polish army of more than 100,000 men.

At the beginning of the war, Piłsudski had convinced Austria and its ally Germany that their manpower problems could be easily remedied by creating three Polish Legions that would fight for the Central Powers in exchange for the establishment of a new quasi-Polish state, the Kingdom of Poland. That weak promise of eventual Polish independence freed the Germans from having to keep a large occupying force in Poland at a time when the war on the Western Front demanded more and more men. For the next three years the Polish Legions fought bravely under the flag of Austria-Hungary, even though the German and Austrian governments remained noncommittal on the matter of Poland’s postwar status.

Seeing an opportunity to acquire additional troops for its own hard-pressed army, Tsarist Russia developed a welcoming policy toward the Poles. In 1914 Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, the commander in chief of the Russian army, issued a manifesto in which he promised a resurrected Poland “reconciled fraternally with Great Russia.” In one of the most striking ironies of war, Poles would find themselves fighting against other Poles for Polish independence.

The winter of 1916–1917 was a time of reprieve for the newly appointed colonel Haller and his 2nd Infantry Brigade. Russia’s gigantic Brusilov Offensive, at a huge loss of life on both sides, had halted the German and Austrian advance on the Eastern Front. For Haller’s brigade, the vicious fighting at the Battle of Kostiuchnówka during the early phases of the offensive had been very costly. Although Haller’s troops valiantly held their positions and were the last to retreat, the general lost some 2,000 men in the battle.

As Haller sat down to dine with his officers on Christmas Eve 1916, the sacrifice of the most recent battle was not lost on him. While fighting under the Austrian flag on the Eastern Front, the Polish Legions faced as many as 200,000 of their own countrymen who shared the same dream of Polish independence. The only difference was that they were fighting with the Imperial Russian Army to achieve it. The history-altering Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of March 1918 would abruptly end that alliance.

After assuming effective control of Russia in late 1917, communist leader Vladimir Lenin immediately decided to withdraw Russia from the war.

As Russia’s withdrawal approached, details of the negotiations between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers leaked to the press. Haller found himself commanding agitated troops who no longer believed that Germany and Austria supported an independent Poland. With the United States now entering the war, Haller and his comrades could see that the tides were turning. They had suddenly found themselves on the wrong side of the conflict.

With its grip on the Poles slipping, Austria-Hungary’s high command attempted to force the members of the Polish Legions to take an oath of allegiance. In a closed-door meeting, the leaders of the three Polish brigades, among them Józef Piłsudski, decided to refuse the Austrian ultimatum, but the commander of the 2nd Brigade did not agree. Haller wanted to find a way for his army to keep fighting for the future of Poland. The next day Haller watched 5,000 soldiers and 166 officers of the 1st and 3rd Brigades of the Polish Legions being led to POW camps at Beniaminów and Szczypiornio.

Playing for time, Haller eventually signed the loyalty oath, while also perfecting a plan to effectively steal the last Polish unit out from under the Austrian flag. He intended to lead the 2nd Brigade across the front lines and join Polish units fighting on the Russian side.

On February 15, 1918, Haller made his move, leading his men under the cover of darkness through the town of Rarańcza in the Carpathian Mountains of eastern Ukraine. Illuminated only by the stars, the men moved quietly, trying to avoid detection, as they approached the weakly defended Austrian line outside of town. Suddenly artillery and machine-gun fire began raining on them. Haller ordered his officers to return fire and keep moving.

Despite suffering heavy losses as they broke through the front, Haller and his forces made it successfully into the Russian lines. Initially, Haller took command of the newly formed Polish 5th Siberian Rifle Division, but he was quickly promoted to general of the Polish II Corps in Ukraine. Meanwhile, he continued to nurse the dream of commanding an independent Polish army and reestablishing his homeland.

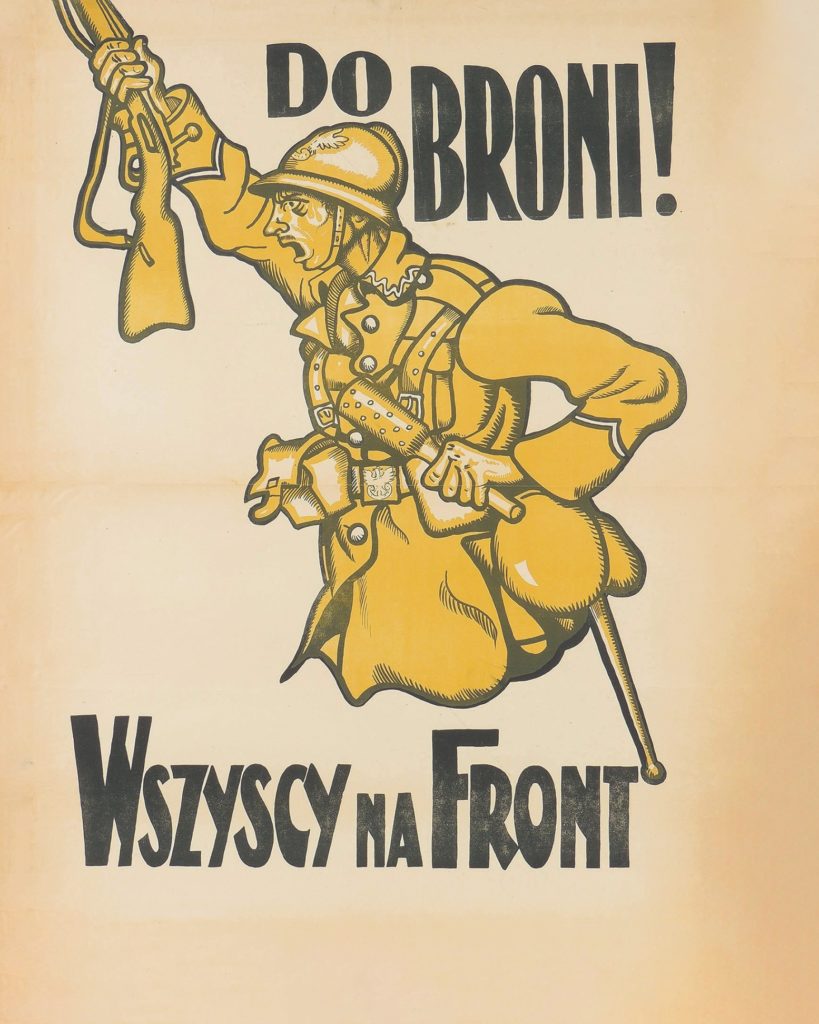

Unbeknownst to Haller, the future independent Polish army that would bear his name was forming in the most unlikely place: the United States. Following the nation’s entrance into the war on April 6, 1917, the U.S. War Department, having sorted out its own selective service campaign, entered the picture. It began helping the Chicago-based Polish National Department, the leading organization of Polish Americans, create a new Polish army.

On October 8, 1917, with President Woodrow Wilson’s blessing, the federal government announced that all Poles who were not U.S. citizens and not subject to the draft could enlist in the new Polish army. The subsequent recruiting campaign exceeded all expectations, especially considering the restrictions attached to it. Within a month of Wilson’s approval, more than 3,000 men had gathered at a specially designated military training camp at Niagara-on-the-Lake in southern Ontario, Canada. The number of recruitment centers doubled within the first two months of the campaign, and by the end of 1917 nearly 6,000 men had begun basic training. At the same time the French government established a Polish army training camp at Sillé-le-Guillaume in northwestern France. The camp was filled with Polish POWs released from Italy, Germany, and France.

By September 1917, the Polish army, which was now being referred to as the Blue Army because of the color of its uniforms, got a boost when 16,000 Poles from French prisoner-of-war camps joined its ranks; the POWs had fought for the Central Powers but now had switched their allegiance. These were experienced soldiers and officers, well trained and indispensable to the newly formed legions. The European recruitment was completed by conscripting a small Polish unit that had fought for the French Foreign Legion since the start of the war.

When Haller led his force across the Austrian front in February 1918, about 12,000 officers and men trained in the United States and Canada had already been transported to Europe to join the Polish units in France. Initially deemed not ready for its own command, the Polish army found itself dispersed among 28 different corps in the various Allied armies. In June 1918, the 1st Polish Rifle Division became the first autonomous Polish unit, fighting alongside other Allied units at the Second Battle of the Marne and helping blunt the last major German offensive of the war.

On the morning of June 23, 1918, Roman Dmowski, who had founded the Polish National Committee to push for the establishment of an independent Polish state, slowly made his way through the wounded troops of the 1st Polish Division. As he looked down on the faces of Poles from the United States, Brazil, Holland, Russia, France, Italy, Germany, and other corners of the world, he could not hide his pride.

Just four days before Dmowski’s visit to the Western Front, the Allies had officially recognized the Polish 1st Division as one of their fighting units. Not since 1812 had a fully autonomous Polish army flying full Polish colors fought on a European battlefield.

On June 28, 1918, a few days after the Polish Division was honored for its valor at the Second Battle of the Marne, Haller walked into the headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force in the Russian port city of Murmansk. Dressed in civilian clothes and exhausted from his long trek across Russia, Haller was eager to reach the new Polish army on the Western Front. Having been briefed on the successes of the Polish army in France, Haller was determined to join them.

Haller declined a commission in the British Army but accepted a berth aboard a Royal Navy vessel sailing from Murmansk to France. He arrived in Paris on July 13 in time to watch Allied units, among them regiments of the Polish 1st Rifle Division, parade down the streets of the French capital on Bastille Day. His future army had not yet united into a single force. Since arriving in France and being dispersed among the French forces, the Polish divisions had suffered 206 killed in action, 862 wounded, and 15 permanently disabled.

In the following weeks, the 1st Polish Division saw extensive action along the Western Front. Besides helping beat back the German offensive at the Marne River, the division captured the town of Auberive and fought off an assault by the German 66th Regiment near Saint Hilaire-le-Grand. After Haller’s arrival and before the consolidation of the Polish forces under his command, the 1st Polish Division saw extensive action along the Western Front, serving with distinction in battles and skirmishes near Rheims, as well as Alsace and Lotharingia.

In a move supported equally by Great Britain and the United States, France officially granted the Polish army autonomous status on September 28, 1918. A week later, Haller stood on a field near Nancy, France, overseeing the formations of his new Polish army, to become known as Haller’s Blue Army.

As he looked over the field, Haller raised his right hand and swore an oath to his mother country: “I am ready to lay down my life for the sacred cause of its unification and liberation, to defend my banner to the last drop of blood, to keep discipline and obedience to military authority, and in all proceedings to guard the honor of Polish Soldiers.”

Haller’s Blue Army was assigned to the front at Alsace in the Vosges Mountains, where it saw limited action. When the armistice was announced on the Western Front on November 11, 1918, Haller’s army was just reaching its full strength: 108,000 troops divided among three corps, seven squadrons of airplanes, and tank and supply regiments.

While the war may have been over for the Allies, it was not yet over for Poland, which now needed the strength and experience of Haller’s Blue Army to secure and defend its new borders.

In the spring of 1919 Haller and his troops entered the Polish-Ukrainian War, which centered on the disputed territory of eastern Galicia, a predominantly Ukrainian enclave regarded by the Poles as part of their historical homeland. After a military group calling itself the West Ukrainian People’s Republic seized control of the provincial capital of Lviv, Polish residents rose up in resistance to the power grab. The Poles took back Lviv, and fighting spread across the region, with neither side gaining a decisive advantage.

On May 14, 1919, Haller’s forces undertook a major offensive aimed at breaking the stalemate in eastern Galicia. Well equipped by their Western allies, Haller’s troops broke through the Ukrainian defenses, eventually reaching the Zbruch River. In June, Haller’s wartime comrade Józef Piłsudski arrived to take charge of the Polish forces. Offensives and counteroffensives continued throughout the summer, before the Allies brokered a peace treaty giving Poland effective control of Galicia. Some 25,000 Polish and Ukrainian soldiers were killed in the short but brutal war.

In the meantime, Haller assumed a new command position in Pomerania. On the blustery cold morning of February 10, 1920, at the seaside retreat of Puck on the Baltic coast, Poles gathered to celebrate their newfound independence. Every half mile along the scores of miles of approaching avenues, garlands were stretched from tree to tree, and in every village schoolchildren threw floral greetings beneath the hooves of the Polish cavalry. At midday, churches in the city sounded chimes and guns thundered in salute as a long column of troops moved toward the beach and the Baltic Sea. Three companies of British marine infantry kept the lines straight as several squadrons of cavalry and French infantry carried multicolored Polish banners.

Haller, on horseback, detached himself from the group and rode into the sea. Turning to address the crowd, he noted the significance of the moment. After 138 years, he said, Poland had once again returned to the sea. On the beach, officers made way for a dozen color-bearers, each holding aloft the standard of a Polish regiment. A Catholic priest stepped forward with his blessing. Haller dismounted and stood in the cold waters of the Baltic. From his finger he drew a golden ring and threw it far into the water, saying, “As Venice so symbolized its marriage with the Adriatic, so we Poles symbolize our marriage with our dear Baltic Sea.”

In the ensuing Polish-Soviet War, Haller would earn praise for his role in the defense of the capital during the Battle of Warsaw, in which he would lose a leg. The Polish victory in the battle against overwhelming odds, fought along the country’s largest river, became known as the “Miracle on the Vistula.” It was a hugely consequential victory, effectively ending Bolshevik efforts to spread communism into Western Europe.

Three years later, Haller came to the United States as a guest of the American Legion. Newspapers hailed him as “the maker of Modern Poland” and “the Sentinel of Civilization.” At the American Legion’s National Convention in San Francisco, Haller found himself treated as a hero and was given a membership pin. He dined with President Calvin Coolidge in the White House and paid a quick visit to automaker Henry Ford in Michigan.

Yet the trip was not without controversy, as rumors spread about the Catholic-dominated Blue Army’s alleged anti-Semitism in Galicia. When 85,000 Jews in Boston protested his visit there, Haller wholeheartedly denied any accusations of discrimination, maintaining that “at no time have I issued edicts, official or unofficial, by sign, word or mouth or intimation, the Jewish people should be treated differently from other nationalities residing in Poland.” According to Haller, the charges revolved around an order for all men, including observant Jews, to have their beards cut off to counter a typhus epidemic raging through Polish military camps. Lice, he said, did not discriminate between religions and creeds. Despite his denials, the rumors would follow Haller for the rest of his life. Reliable studies have found that several hundred Jews, in fact, were killed by the Blue Army or paramilitary groups in Galicia during the Polish-Ukrainian War, although there were no organized pogroms against Jewish residents.

Haller left the army in May 1926, following a military coup by Piłsudski, his erstwhile comrade, that overthrew the democratically elected government.

After leaving the army, Haller quietly retired to Pomerania, on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. When World War II broke out in 1939, the 66-year-old one-legged general asked the Polish consulate in Great Britain for a commission, only to be rejected because of his age. Instead, he put his experience to use as a minister without portfolio, traveling to the United States in late 1939 to encourage Poles to enlist in the Polish army in France. Following the fall of France, Haller escaped to Great Britain, where he served the government in exile as a minister of education.

When the war was over, Haller remained in London. The man who as a child had dreamed of a free Poland and had grown up to command the army of the independent nation, died alone in his London flat on June 4, 1960. After the fall of communism three decades later, Haller’s remains were returned to Poland and placed in a crypt in St. Agnieszka’s garrison church in Kraków. He was home again—this time for good. MHQ

Peter Zablocki is a historian and the author of Denville in World War II, which will be published in 2021 by the History Press.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Poland’s Men in Blue and Their Struggle for Independence

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!