Herman Melville (1819–1891) turned to poetry only after his serious fiction played to the literary equivalent of an empty house. Even Moby-Dick, the magisterial whaling story that for more than 100 years has been considered his magnum opus, was trashed by reviewers on its publication in 1851 and sold barely more than 3,000 copies during Melville’s lifetime.

In March 1861 Melville went to Washington, D.C., in search of a job. While there he attended a party at the White House given by the new president, Abraham Lincoln, and raptly watched the U.S. Senate as its members debated secession. When the Civil War broke out the following month, Melville volunteered for a second tour of duty in the U.S. Navy but was rejected on account of his poor health.

The war continued to make a deep impression on Melville. In April 1864 he and his brother Allan, having obtained U.S. government permits to visit the battlefields south of Washington, D.C., traveled to Virginia to visit their cousin, Lieutenant Colonel Henry S. Gansevoort, and ended up on a scouting mission searching for the Confederate rangers led by John S. Mosby, the cavalry commander whose guerrilla tactics were plaguing Union troops in the Middleburg area.

The war also furnished the subject of Melville’s first published volume of poetry, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), which he dedicated “to the memory of the Three Hundred Thousand who in the war for the maintenance of the Union fell devotedly under the flag of their fathers.” Many of the 72 poems in the book, including the one reprinted here, refer to specific battles. (The Battle of Shiloh, fought April 6–7, 1862 in southeastern Tennessee, was one of the war’s bloodiest, with more than 3,500 men killed and nearly 15,000 wounded.)

Four months after Battle-Pieces was published, Melville finally landed a job as a customs inspector in New York City. Even though Battle-Pieces was, like Moby-Dick, a commercial failure (it sold fewer than 500 copies in eight years), Melville continued to write poetry until his death, from a heart attack, at age 72. A few days after his death the New York Times observed that Melville was “so little known, even by name, to the generation now in the vigor of life that only one newspaper contained an obituary account of him, and this was but of three or four lines.”

Shiloh: A Requiem

Skimming lightly, wheeling still,

The swallows fly low

Over the field in clouded days,

The forest-field of Shiloh—

Over the field where April rain

Solaced the parched ones stretched in pain

Through the pause of night

That followed the Sunday fight

Around the church of Shiloh—

The church so lone, the log-built one,

That echoed to many a parting groan

And natural prayer

Of dying foemen mingled there—

Foemen at morn, but friends at eve—

Fame or country least their care:

(What like a bullet can undeceive!)

But now they lie low,

While over them the swallows skim,

And all is hushed at Shiloh.

[hr]

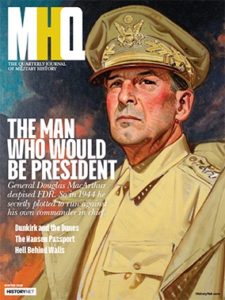

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: What like a Bullet…