In 1950, a Washington, DC, restaurant turns away an elderly woman because she is black. The court case she sparks lays the framework for the end of segregation. In Just Another Southern Town, Joan Quigley tells the story of Mary Church Terrell, an unlikely civil rights hero whose life spanned the Emancipation Proclamation and Brown v. Board of Education.

What was Mary Church Terrell’s context? Mary’s story is at the complicated intersection of race, gender, and class. And class is part of the explanation as to why she spent a lot of her life seeking better treatment. Her father, Robert Church, was the son of a slave mother and a white master. Robert’s father gave him a job working on Mississippi riverboats. He became an entrepreneur in Memphis. Her mother, Louisa, also daughter of a master and a slave, benefited from a special relationship with her father.

What were her mother’s hopes for Mary? Louisa aspired for Mary to have an education. That wasn’t possible in Memphis, so Mary was sent north to school, perhaps as early as age six. Her first schooling was in Yellow Springs, Ohio. She moved to Oberlin, Ohio, for high school and college.

How was life there for her? This region of Ohio was a hotbed of transplanted New England abolitionism that offered opportunities for a young black woman. Mary sang in a Congregationalist church choir and lived at first in a rented room. She was raised by Oberlin—the town, and then the college. Oberlin College was unique—almost from its very start in the 1830s, it was coeducational and admitted African-Americans. Mary lived in a ladies’ dorm and socialized with black and white students.

Tell us about her husband. Robert Terrell’s parents were former slaves from Virginia who came to DC after the Civil War. Robert graduated from public schools and went to Boston, where he got a job waiting tables in Harvard’s dining hall. Students encouraged him to enroll. When he graduated in 1884, he was chosen to give a commencement speech. He got a law degree from Howard University and in 1901 became a DC justice of the peace—a prestigious position but without lifetime tenure. Every four years, he and other municipal judges in Washington had to be renominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. For the rest of Robert’s life, every president—even southern sympathizer Woodrow Wilson—reappointed him.

He and Mary had to tread cautiously. Robert was at the mercy of the political process. There was tension between what Mary wanted—to draw attention to the cause of racial equality—and the reality that her husband needed and wanted to keep his job.

Why did Mary take up lecturing? Lecturing gave her a platform and an opportunity to raise issues she cared about and to raise money. She wrote for magazines and spoke on the Chautauqua self-improvement circuit.

What was early-1900s DC like? Segregation hardened. In 1908, on a Washington streetcar carrying a suitcase, Mary asked a white man to move. He wouldn’t. She slapped him. She couldn’t get served at a soda fountain.

She found ways to lead. Mary was the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, founded in 1896, two months after Plessy v. Ferguson.

What about the NAACP? Mary became a charter member in 1909 but otherwise didn’t have a visible role.

How did she fare after Robert died in 1925? She wrote a memoir, A Colored Woman in a White World. Based on her Oberlin degree, she applied to the local branch of the American Association of University Women. The branch rejected her. She sued. In June 1949, the DC federal appeals court sided with the branch. Civil rights was stalled in Congress. In DC, segregation was practiced in churches and schools, department stores, businesses, movie theaters, and drug stores—everywhere but on streetcars, at Union Station, and in government cafeterias.

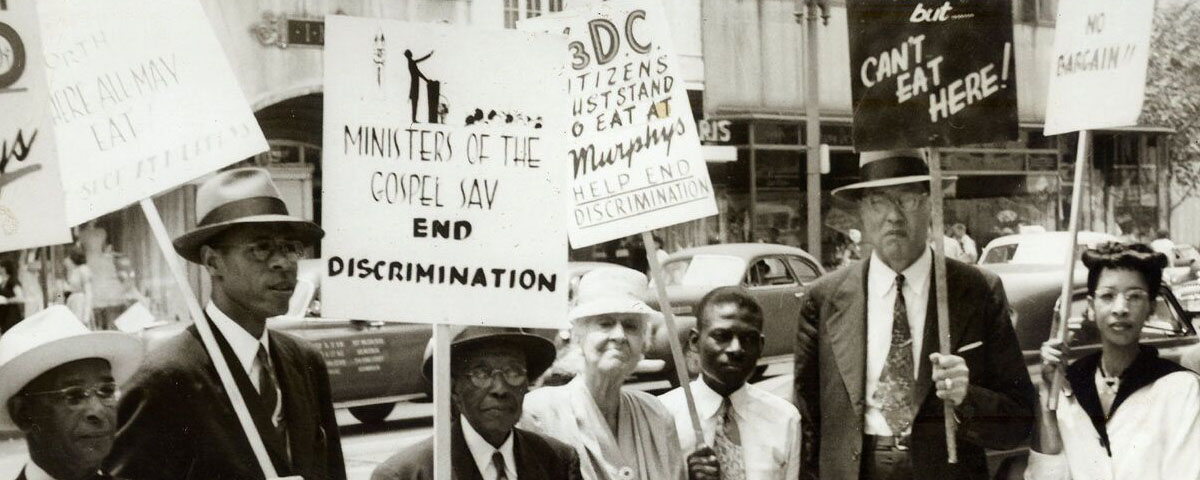

How did she go after Jim Crow? On January 27, 1950, four activists meet at Thompson’s, a cafeteria at 725 14th Street NW, near the White House. Mary Church Terrell is 86. Mount Carmel Baptist Church minister William Jernagin is in his 80s. Their companions are Geneva Brown of the Cafeteria and Restaurant Workers Union and David Scull, a white Quaker.

What happens? The manager says Thompson’s can’t serve the four because they’re “colored.” Jernagin says, “I can’t be served because my face is black?” The manager says, “It’s not you, it’s company policy.”

That was what they had come for. At the time, Reconstruction-era laws on the books in DC banned racial discrimination by restaurants. Mary and company were seeking to revive those laws. The denial enabled them to file affidavits that would be the basis for challenging restaurant segregation in Washington. The case wound its way from the DC municipal court to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, and at every level Mary and her allies lost. The case went to the Supreme Court, which in December 1952 had heard oral arguments in the group of cases known as Brown v. Board of Education. The Justices couldn’t resolve Brown. But in April 1953, up came Thompson. The high court took the case on an expedited basis, immediately scheduled oral arguments, and on June 8, 1953, issued a decision.

Explain the legal mechanics. Unlike the Brown cases, Thompson wasn’t a constitutional matter. The Justices didn’t have to rule on the 14th Amendment or the equal protection clause. The case Mary and her allies brought only applied to DC and its obscure old laws. Their case gave the court a chance to send a unanimous 8-0 signal that Jim Crow was over, setting the stage for Brown. The Thompson ruling took effect right away.

What did Mary do? She went to Thompson’s, got in line, and got her food. The manager took her tray and carried it to the dining area.

What does the decision mean to her? It’s everything she’s fought for, a statement by the highest court in the land that she deserves to be treated like everyone else.

Did she write about it? Mary was 89, and starting to feel her age. She lived to see Brown, but died soon after.

- What did Brown mean? Brown brought the nation to the unfinished business to which Lincoln referred in the Gettysburg Address. This decision reversed the backsliding of the Jim Crow years and delivered on the promise of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments.