PLEASE DON’T SHOOT THE PIANIST; HE IS DOING HIS BEST. That saying entered Western lore from an unlikely source—Oscar Wilde. The celebrated Irish poet and playwright did a lecture tour of the United States in 1882 that took him to Western mining camps. While declaiming in a saloon in Leadville, Colorado, he read those words on a sign over the piano.

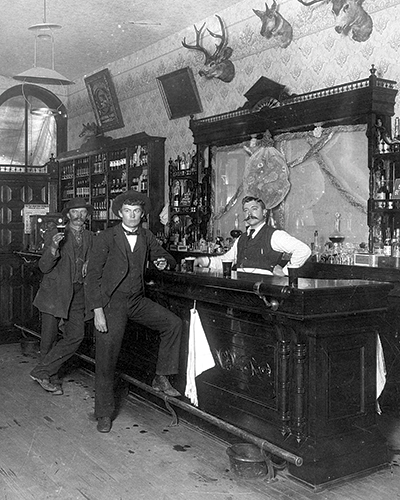

The plea might also apply to bartenders, who, like their piano-playing colleagues, tried to do their best in often trying circumstances. Tending bar in the Old West could be dangerous work, and a good saloon man was not easily replaced, as he was far more than a simple drink pourer. Reflecting in 1931 on his own pre-Prohibition saloon visits, writer Travis Hoke described the ideal old-time barkeep as “a counselor in all the ways of life, recipient of confidences, disburser of advice, arbiter of disputes [and] authority on every subject.”

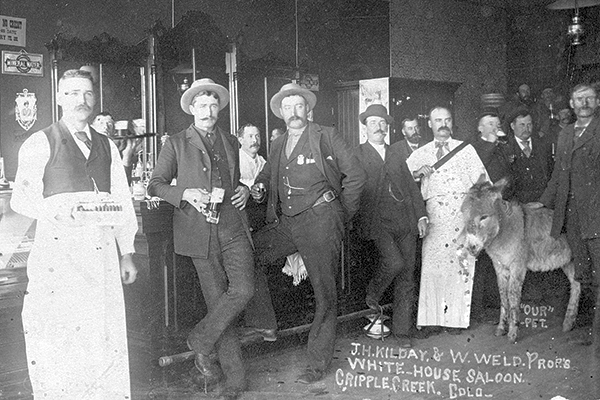

A bartender was not necessarily the barkeep (or saloon proprietor) and vice versa, though newspapers on the frontier used the terms interchangeably. Like every other business owner, a saloon man had to be willing to roll up his sleeves and go to work. That meant getting behind the bar. One too proud to tend bar was not likely to be successful. In 1885 saloon man John T. Leer of Fort Worth, Texas, bought out his partners in the Theatre Comique, and most nights he tended bar. To lure patrons from rival saloons, Leer shrewdly slashed the price of drinks, knowing most men weren’t there for the variety show.

There were no qualifications for being a bartender. In the early years few even knew how to mix the specialty drinks that came to be known as cocktails. Patrons could order either beer or whiskey. It was a bartender’s option whether to serve the good stuff or the “Who Hit John.” An absolute no-no was dipping into an employer’s stock. That could get a man fired as quickly as dipping into the till. Unfortunately, one of the temptations of working behind a bar was access to an endless supply of booze. For one inclined to alcoholism that could prove fatal one way or another. If a bartender with the habit didn’t drink himself to death, he might get into a drunken brawl with a customer and die of “lead poisoning.”

A man with ready access to both liquor and guns could be a dangerous hombre. If he had psychological problems to boot, he was a ticking time bomb.

On Aug. 6, 1886, saloon man John W. Vaden got drunk, armed himself with a Winchester and shot out the lamps in his own establishment in Ballinger, Texas. He then barged into the neighboring Palace saloon, spoiling for a fight with bartender Frank Borman. City Marshal Tom Hill responded to the fracas, and amid a three-way struggle for the rifle he was shot through the left foot. A doctor had to amputate, infection set in, and Hill died two days later. Skipping town, Vaden repeated his performance that October 7 at Mayer’s saloon in Fort McKavett, Texas, smashing up the place and threatening bartender Ben Daniels with a hooked pole until the latter, who doubled as a deputy sheriff, shot Vaden dead.

On June 22, 1887, Fort Worth saloon man William T. Grigsby was tending bar and reportedly sampling the whiskey at his Unique saloon. Around 1 p.m. he asked the bartender to hand him his pistol from beneath the counter and a bottle to take home. Instead of leaving, however, he began pacing the floor, muttering darkly to himself. Among those present was friend Mike Haggerty. Seeing that his pal was troubled, Haggerty approached Grigsby, asking for the gun. Without a word Grigsby drew down and shot his friend dead. The saloon man then began raving and sobbing incoherently. It took several policemen to subdue and haul Grigsby off to jail. “He had the reputation of being a quiet, gentlemanly and clever man,” noted the Fort Worth Gazette, “who had not an enemy on earth.” Something that day sent him over the edge. The paper noted Grigsby had been drinking heavily and stewing about a recent local debate over prohibition. When he came to his senses in jail, officials released him on a bond posted by friends who passed off the episode as a case of temporary insanity brought on by bad whiskey. Grigsby was indicted for murder, but his lawyers dragged out the case for nearly two years before it went to trial. By that time the prosecution had no witnesses and thus no case, and a jury acquitted him. Proving one can’t keep a good bartender down, in 1907 Grigsby, then living in North Fort Worth, was granted another saloon license.

it was a reputation for sterling character that made a bartender a trusted member of the fraternal community

As a rule, however, it was a reputation for sterling character that made a bartender a trusted member of the fraternal community. Sporting men who would bet on anything frequently asked a barkeep to hold the stakes. In October 1880 Fort Worth marshal turned gunfighter Thomas Isaiah “Longhair Jim” Courtright and gambler John C. Morris agreed to settle their differences with knife duel, each man putting up his gold watch as collateral he would show on the appointed date. Whom did they trust to hold the stakes? A friendly bartender, of course. The fight never came off, and each man reclaimed his watch. Barkeeps themselves typically refrained from gambling while on duty. It was better not to get involved beyond holding the stakes and sometimes the bankrolls of players.

An important part of the job was knowing how to handle both the inebriated customer and the garrulous fellow who wanted to buy the bartender a drink. The former had to be cut off without causing offense, the latter politely refused. A barkeep also had to be able to ride herd over rowdier patrons without hurting business. It helped to have a tough guy reputation. Saloon man “Rowdy Joe” Lowe, who bounced among the Kansas cow towns before moving to Fort Worth, was quite capable of corralling his patrons. “I keep good order in my house,” he bragged, and by all accounts he was able to back up the boast. “If any man becomes disorderly, and there is no officer of the law present, I am very apt to take the law into my own hands.”

Whether he was the proprietor or just tending bar, a saloon man was expected to keep a rough kind of order. “Bouncer” was part of the job description for a job that might pay $2 for a weeknight shift or $3 for a weekend shift. Being an enforcer could be dangerous. On March 1, 1872, an inebriated “Cherokee Dan” Hicks entered Harry Lovett’s Side Track saloon in Newton, Kan., and began taking potshots at the mirrors and pictures on the wall. When the rowdy refused to holster his gun, Lovett whipped out his own six-shooter and dropped Hicks with three slugs to the body and one to the head. No charges were forthcoming. Such violence was not limited to the frontier. On Sept. 13, 1913, Fort Worth bartender Harry Seidl decked an intoxicated customer who was being obnoxious. Seidl had nothing against the man personally and leaned down to pull the drunk to his feet. Just then one of the man’s friends stabbed the bartender in the back, perforating a lung. The two men fled the scene, while Seidl headed to a hospital. Ironically, he had recently resigned from the Fort Worth Fire Department to take up bartending, as the latter profession was reputedly less dangerous and offered better hours.

Indeed, most scuffles between bartenders and customers resulted in little damage to the combatants or the establishment and were quickly forgotten. Seldom did anyone hold a grudge. If police inquired about any brawls between customers, bartenders were inclined to keep mum, as a saloon man with loose lips might lose business or be targeted by the accused’s friends. It was better to see and hear nothing while working behind the bar.

Bartender D.S. Randall of Fort Worth’s Blue Light saloon was the sort who kept order with a light hand, though he was no pushover. Ben Tutt, a regular known to have a foul temper when in his cups, was already well lubricated when he entered the Blue Light on the evening of April 9, 1877. Bellying up to the bar, Tutt demanded a free drink, and Randall poured it. After downing his whiskey, Tutt pulled a pistol and shot wildly, grazing Randall in the shoulder. Ducking behind the bar, Randall came up hurling bottles at his assailant before pulling a six-shooter and opening fire. Fleeing from the saloon without a scratch, Tutt toddled off down the street. Police soon arrested him, but Randall refused to press charges, as Tutt was a loyal patron and the incident just another night manning the bar.

Inebriated bravos demanding free drinks was not unusual. Bartenders handled it differently depending on the situation and the customer. On Dec. 30, 1894, Jim Rushing was barhopping in Fort Worth with friend Bob Miller when they entered city alderman Martin McGrath’s saloon and sauntered up to the rail. Miller pulled his pistol, laid it on the bar and demanded drinks. Though he didn’t utter any threats, McGrath’s bartender got the message and poured drinks for the pair. Miller had pulled the same stunt in at least one other saloon that night, but the difference this time was proprietor McGrath. When a scuffle broke out between the Rushing party and other patrons, McGrath descended from an upstairs room with pistol in hand and opened fire. When the smoke cleared, Rushing lay dead on the floor. The bartender on the night of the shooting had been a new hire, called in to handle the coming New Year’s Eve rush. “I didn’t do nothing at all,” he testified of his actions that night. “I just stood right there. Never moved.” After the body had been removed, McGrath directed his bartender to lock the doors of the empty saloon. Convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to nine years in prison, McGrath later escaped and was never heard from again.

When not defending themselves or their saloons, bartenders tried to be hospitable. They were, after all, the “face” of the establishment. They had to walk a thin line between letting the boys blow off steam and keeping a lid on things. That meant being tough when they had to be tough and remaining congenial the rest of the time. Little surprise then that many bartenders were former lawmen or outlaws and thus no strangers to violence. Between stints at the bar some returned to lawlessness. Others were working lawmen, looking to pick up extra cash while passing the time in congenial surroundings.

In the words of Western writer and historian Walter Noble Burns, the best bartenders “dispensed good fellowship as well as good liquor.” Every now and then, though, the job proved dangerous or even fatal. One never knew when death might push through the batwing doors. Bob Ford, the notorious assassin of outlaw Jesse James, was working as a bartender in Creede, Colo., on June 8, 1892, when ne’er-do-well Edward “Red” O’Kelley strolled in with a shotgun, called out, “Hello, Bob,” and shot down Ford in cold blood. O’Kelley thought killing the man who killed James would make him a hero. Ford himself could have told his murderer it didn’t work that way.

Frontier-era papers are chock-full of stories about men who walked into saloons and opened fire for no apparent reason. Perhaps some had fallen into bad whiskey, or maybe they were on the prod. Others were seemingly psychotic. According to court testimony, Frank Fossett, one murderous habitué of saloons, reportedly once said he would “like to have a saloon out in the country…so he could kill a bartender every week or two.”

Sometimes a bartender was in the wrong place at the wrong time. On Jan. 14, 1877, inebriated Fort Worth saloon man John Leer, future proprietor of the Theatre Comique, rode his horse through the doors and up to the bar of a competitor’s saloon, pulled a pistol and ordered a drink. After serving Leer, the bartender promptly summoned police, who came and arrested the drunken saloon man. Tendering bail, Leer promptly returned to the competitor’s place and fired five shots through its glass door, wounding proprietors John Stewart and Henry McCristle. The still-inebriated Leer spent the night in jail and paid a fine, but his victims were apparently unwilling to file charges.

On Sept. 1, 1893, when a gun battle erupted between the Doolin-Dalton Gang and lawmen on the streets of Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory, among the casualties was a barkeep and patrons of saloons in which the gang holed up.

Walter James, bartender and co-owner of Fort Worth’s Board of Trade saloon, likely expected trouble when Walker Hargrove strode up to his bar around 5 p.m. on May 20, 1908. A mean drunk whom James had ordered out a week earlier, Hargrove had vowed vengeance. Declining the latter’s offer to share a drink, James served Hargrove a shot of whiskey, then turned to serve other customers. After tossing back his drink, Hargrove smashed the empty glass on the bar. James then consented to share a drink with Hargrove, but the bully wasn’t satisfied. Cursing James, he grabbed for the gun at his hip and started around the bar. Reaching beneath the counter, James pulled his own pistol and plugged his would-be assailant three times, the last a kill shot to Hargrove’s head. A jury acquitted James of all charges.

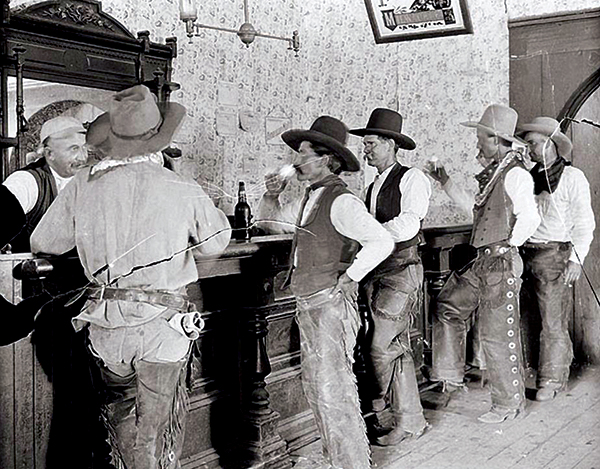

It was in trail towns that bartending was most perilous. Cowboys looking to blow off steam after days spent castrating steers or trailing herds could be mercilessly hard on the man behind the bar. Hands from the LS Ranch outside Tascosa, Texas, enjoyed taunting bartender Lem Woodruff of the Dunn & Jenkins saloon. Former Texas Ranger Ed King was especially galling, calling Woodruff “Pretty Lem” and ultimately stealing away his girlfriend. In the early hours of March 21, 1886, Woodruff and cohorts got their revenge, gunning down King and two other LS hands. Woodruff and a cohort were wounded, while bystander Jesse Sheets was killed in what was recorded as the bloodiest gun battle in Tascosa history.

It wasn’t just rowdy cowboys who posed a threat to life and limb. Western gunslingers thinned the bartenders’ ranks, some by accident or misfortune, others with cool deliberation. On April 16, 1881, Bat Masterson, in defense of brother Jim, went gunning for Dodge City saloon man A.J. Peacock and bartender Al Updegraff of the Lady Gay. Peacock fled, while Updegraff was wounded. A few years later, on Aug. 19, 1884, Doc Holliday shot and wounded Monarch saloon bartender Billy Allen in Leadville, Colo., after the latter threatened the notorious gambler over unpaid debts. The victims recovered, and neither shooter faced serious consequences.

to persevere as a bartender, a man had to be as tough as his customers

To persevere as a bartender, a man had to be as tough as his customers. On the afternoon of June 21, 1880, Billy Thompson, younger brother of gunman Ben Thompson, got into a dispute with barkeep Bill Tucker of Ogallala, Neb., over the affections of a local prostitute and stormed out of the saloon. Returning with a gun, Thompson snapped a few shots at Tucker, who at the time was “in the act of passing [a patron] a glass of whiskey with his left hand.” One bullet took off Tucker’s thumb and three fingers on that hand. Thompson turned and coolly strolled out, while the saloon man crumpled in a bloody mess. But his assailant had walked only a few yards when Tucker came charging out from behind the bar with double-barrel shotgun. From the door the saloon man steadied the gun across his maimed hand and emptied it into Thompson’s backside. Patrons tended to Tucker’s injuries and manhandled the wounded Thompson over to the Ogallala House Hotel to recover before trial. With help from Bat Masterson, Thompson managed to flee the state and swallow what remained of his pride.

It is unclear whether Tucker continued to tend bar with a mangled left hand. If he did return to work as a one-handed saloon man, he would not have been the first or last crippled bartender. Indeed, many Old West barkeeps would have been eligible for protection under the provisions of the present-day Americans With Disabilities Act, as a surprising number of them were missing various limbs and appendages. Fortunately, the job did not require ten fingers, let alone both arms or legs, and it was well-paying, unskilled labor, making it a viable retirement option for battered outlaws and lawmen who’d hung up their guns.

Still, as Garry Radison reminds readers in his book Last Words: Dying in the Old West, bartending was one of the truly “dangerous occupations” in the West. Of course, barkeeps were not always the victims, and those who shot rowdy customers were seldom prosecuted. On the rare occasion when a case went to trial, the all-male jury, often comprising patrons of the very establishment the accused tended, often chose to acquit.

Race was seldom a factor in saloon shootings, as in most jurisdictions blacks weren’t permitted to enter white-owned establishments. That said, the chances of conviction, or even prosecution, were slim indeed if the bartender was white and his victim was black. In 1911 barkeep F.E. St. John of Fort Worth’s Phoenix saloon shot black co-worker Buzz Childers, the saloon’s porter. St. John, who’d tended bar for 19 years and had a clean record, claimed Childers had threatened him with a knife, though he gave no reason. No charges were filed.

Race did enter the equation if officers were summoned to a black-owned bar, as the all-white police forces in towns like Fort Worth were hostile to any black who failed to show what was considered “proper deference.” In 1909, for example, Fort Worth officers were summoned to a police shooting at a bar owned by George C. Cosey. As detective Lee Tignor wrote in his report, he was interrogating the black proprietor, trying to “gather information on a matter under investigation,” when Cosey “began to abuse me in a shameful manner.” Things went downhill quickly, and both men pulled guns. Tignor emptied his revolver at Cosey, mortally wounding the saloon man. The detective’s report ended the matter as far as a grand jury was concerned.

Ultimately, like the Old West itself, bartending became more civilized. In 1885 one El Paso bar owner explained to a reporter how his profession had evolved. “When I first opened here,” he said, “it was the fashion to shoot bartenders on the slightest provocation. I had to employ men who would shoot back—nervy devils who knew their lives were at stake.” As the town grew up, however, the saloon began to attract a better class of customers. At that point the proprietor had to replace his old scrappy barkeeps with more gregarious fellows. Then, as cocktails became increasingly popular, he had to hire “mixologists.” By then, he told the reporter, he was employing men “with the dignity of a judge and the polish of a gentleman.” His only concern was keeping patrons happy, as that kept the cash register ringing—and a happy customer was less likely to plug the bartender. WW

Richard Selcer of Fort Worth, Texas, is a frequent contributor to Wild West and the author of such well-received books as Hell’s Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District and Fort Worth Characters. Selcer is also the editor and compiler of Legendary Watering Holes: The Saloons That Made Texas Famous.