Even after U.S. outlawed piracy, American captains made millions with letters of marque

On May 06, 1827, Captain Thomas Byrne, aboard his commercial schooner Isabelle, was about to leave the Gulf of Mexico for the short journey up the Mississippi River to his home port of New Orleans, Louisiana. Byrne had departed Brazos Santiago, Mexico, with a mixed cargo, along with $30,000 in gold, receipts for previous trade. Isabelle was a mile and a half into American waters, with a mile and a half to go to reach the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi, one of the big river’s three concluding channels. The pass is the southwestern-most tip of the Mississippi Delta. In Byrne’s day as today, the waters outside the pass often harbored vessels sailing or at anchor, undergoing repairs, pausing before traveling the final miles upriver to New Orleans, or waiting to engage the services of a pilot to guide them to port. At that time a group of seven pilots, working out of a station onshore, offered their services from small schooners known as pilot boats. River pilots did a good business. Savvy navigators knew that, though even at low tide the pass was 18 feet deep at its center, with no shoals. Along either shore—and especially at turns in the river—lurked sunken tree trunks and hidden mudbanks able to ensnare a hull.

A sloop flying the British flag approached Isabelle. Through a speaking trumpet, a voice asked the American vessel’s name. Such interactions were not unusual; by such means passing crews routinely exchanged ships’ names, home ports, destinations, and incidental news. When Byrne identified Isabelle, the men on the other sloop hauled down the Union Jack, hoisted Colombian colors, and through the trumpet identified their vessel as the General Bolivar, a privateer, or commerce raider. The Americans watched as the other crew, some of whose members were armed with muskets, loaded cannons on Bolivar’s forecastle and at either side. The Bolivar’s captain ordered Byrne to back sail, using the wind to halt his vessel. The American refused. “Heave to or I shall fire into you,” Bolivar’s captain replied. In American waters, only government vessels, such as a U.S. Navy warship or a federal revenue cutter, had the authority to stop an American vessel. Bolivar was engaging in piracy. “If you will, then you must do so and be damned,” Byrne answered. He ordered his helmsman to catch the wind for a run to the safety of the pass.

Isabelle and crew were only the latest targets to come within striking distance of a new offshoot of an ancient breed. The privateer General Bolivar, an armed sloop nearly 67 feet long, displaced a little over 114 tons. A single mast with fore-and-aft rigging and a copper-bottomed hull gave Bolivar enough speed and maneuverability to overtake almost any vessel. The sloop’s three guns—probably a 12- or 18-lb. long-barreled smoothbore on a pivot at the forecastle and at either side smaller carronades—were three more than most targets carried.

Bolivar had been busy. That spring, captain and owner François Reibaud and crew—mostly Americans of French descent hailing from New Orleans—had been patrolling off Cuba when they spied the Spanish merchant brig Xerxes. The brig carried six guns and an oversize crew to defend against predators such as Bolivar but even so, the privateer captain brought the merchant vessel to heel, then boarded and seized ship and cargo. When Spanish coast guard vessels gave chase, Reibaud, daring shallows among the Tortugas, cut through the Florida Keys into the Gulf of Mexico. He arrived at Mobile, Alabama, on March 17, 1827, with Xerxes accompanying. The Mobile federal admiralty court ruled Xerxes a “good prize”—that is, captured in accordance with the privateer’s license—and allowed Reibaud to claim that ship as well as to reprovision and repair his vessels in the harbor. Reibaud also nosed around for intelligence on shipping. His curiosity came to the attention of the local deputy customs collector and Captain Robert W. Bateman, master of the American schooner Marie Antoinette, soon to depart for Tampico, Mexico, on a scheduled cargo run. Warned to lay off Antoinette, Reibaud said he would. Antoinette departed on April 12. On the afternoon of April 15, Captain Bateman noticed Bolivar at Antoinette’s stern. The vessels jockeyed through the night, Antoinette trying to evade, Bolivar sticking close. In the morning, roughly halfway to Tampico, Bateman hove to, launched an oar boat, and rowed to Bolivar.

Piracy’s heyday in the Caribbean had ended nearly 100 years earlier. In the previous ten years, Americans had crossed the Atlantic to stop marauders known as “corsairs” from preying on the new nation’s shipping in the Mediterranean Sea. However, in the Gulf of Mexico and along the Florida coast, pirates now were taking hundreds of American ships.

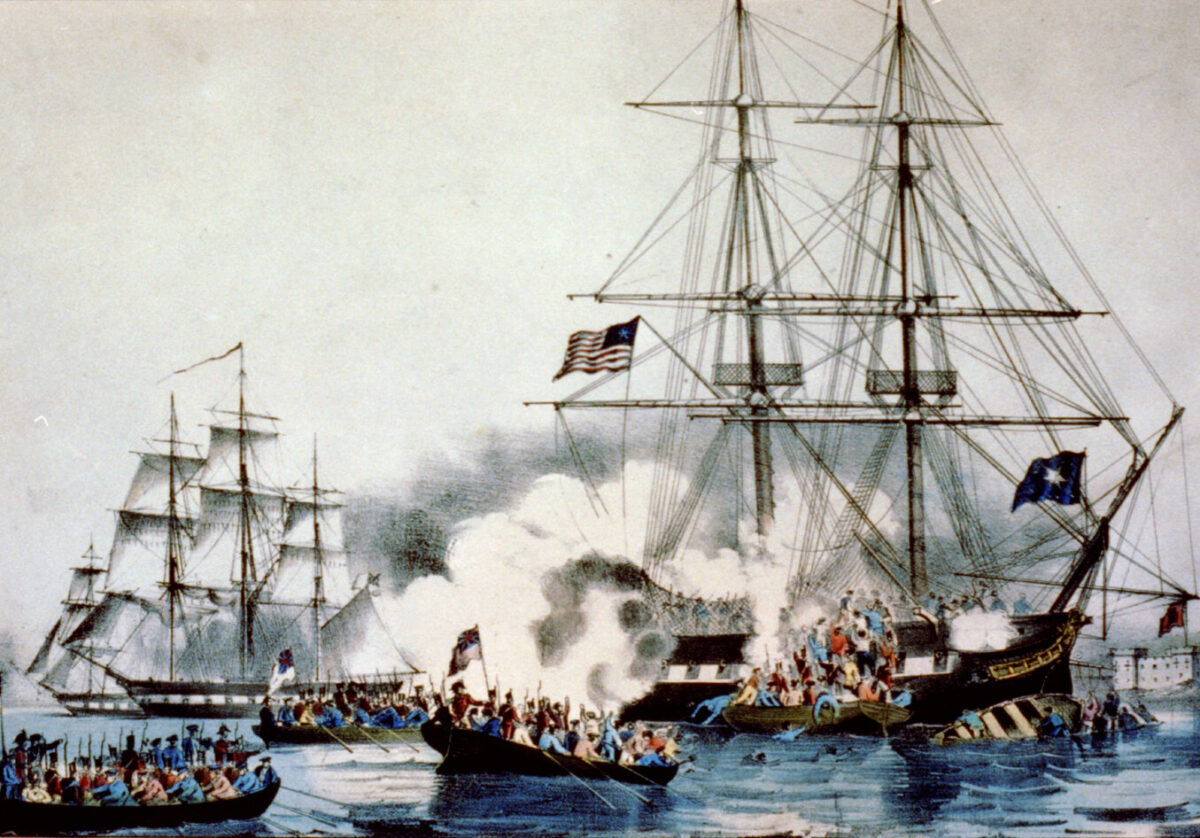

The United States had brought the situation upon itself. In the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy, whose few frigates individually outclassed any other warship, found itself overwhelmed and bottled up by the vast Royal Navy. To compensate, the United States reverted to a medieval tradition that had served well in the Revolution and in later confrontations with France: privateering.

Blending self-interest and strategy, privateers, licensed by official government “letters of marque,” sailed purpose-built armed vessels with oversized crews, pursuing transports flying a foe’s flag. Seizing ships and staffing them with those extra men, led by an officer known as a “prize master,” privateers made their money selling captured ships and cargoes—in effect, legal piracy. A privateer was required to bring a captured vessel into a friendly or neutral port and file in admiralty court to have vessel and cargo condemned. If the captain had obeyed his letter of marque, the court would rule his prize “good” and allow sale of the ship and cargo. The proceeds, minus court costs, went to the master of the privateer for distribution according to whatever agreement the privateer’s owner had with officers and crew. A privateer disobeying the rules, for example by seizing a vessel whose flag his license did not specify, physically abusing or robbing prisoners, might be fined or have his seizure disallowed. Instances of murder, torture, or deliberately misrepresenting a prize’s flag, could face prosecution.

Privateers were an American economic engine in the early 19th century even before they began grabbing British merchant shipping. Shipwrights in Baltimore, Savannah, New Orleans, and other American ports built, launched, and sold nearly 250 privateers that in the course of the War of 1812 captured almost 2,000 ships, costing Britain millions of pounds in lost commerce. Successful privateers made their owners and captains rich, and officers and crews prospered on their shares of the take. The party ended in 1815 when the Treaty of Ghent restored peace between the United States and Britain. However, the war had loosed a huge fleet of privateers superb for piracy, but, like their crews, ill-suited to peacetime.

Ordered aboard Bolivar, Bateman found First Lieutenant August Chicot in command; Reibaud had remained in Mobile, overseeing repairs to the captured Xerxes. Trying to force Bateman to say he was carrying Spanish cargo—he was not—Chicot threatened to tie his prisoner to a gun and flog him until he broke. Even a forced false confession would have legitimized the privateer’s seizure of Antoinette. Bateman stood fast. Chicot relented, offering to let the other sailing master keep his vessel and $2,000 if he would confess. Bateman said no.

Chicot never did have Bateman flogged, but he did take Antoinette as a prize. Chicot in Bolivar escorted the captive vessel and its seven-man prize crew to Tampico. Mexican authorities, acceding to a protest by the U.S. consul, refused to certify the seizure as legitimate. Intending to sell ship and cargo to smugglers in New Orleans, Chicot sailed Antoinette 840 miles northeast. The morning of May 6, 1827, Bolivar and Antoinette paused just outside the Southwest Pass, with its complement of waiting vessels. Chicot told the prize crew to remain well offshore while he made a deal.

The fraying of the Spanish Empire offered a market for the ships and the skills that went with privateering. Former Spanish colonies including Mexico and Colombia offered to reflag American schooners and sloops of war and issue their American owners and crews patentes de corso—letters of marque—authorizing them to harry Spanish shipping. That was what Reibaud and crew had done with Bolivar.

The notion of privateering initially appealed to many Americans, who reveled in the mercenaries’ success at weakening Spain and aiding fledgling independence movements in Mexico and Colombia. And the American economy benefited. Building, rebuilding, and provisioning privateers, as well as prize-taking and the subsequent auctions of purloined ships and cargo particularly enriched Baltimore, New Orleans, Savannah, and other privateer ports.

In 1819, however, Spanish protests and federal ire at the tax-free smuggling of seized goods and ships led to the enactment of the Anti-Piracy Act. That law barred American citizens from serving aboard vessels attacking foreign ships flagged in nations with which the United States was not at war; outlawed outfitting and arming privateers in American ports; and banned privateers from recruiting crews domestically. Prosecutions under the law were rare, however, unless the case involved the death of an American man or a woman or child of any nationality—until rapacity drove privateers to do as Chicot had.

After leaving the seized Antoinette, Chicot attacked Isabelle. When Byrne ran for the Southwest Pass, Bolivar’s crew fired a musket salvo, driving the other vessel’s passengers and most of its crew, including the helmsman, below. Byrne took the wheel. The next 30 minutes saw the pirates keep up a musket barrage and send four charges of grapeshot and a round shot his way, shredding sails and rigging. Byrne slowly put distance between his ship and his pursuers.

At the Mississippi’s mouth, Chicot launched a boat whose oarsmen rowed fast enough to gain on his prey. Isabelle, aided by an incoming tide, was pushing upstream against a 1½-knot current. Sailing “close hauled”—trying to keep the sails filled and still move forward—the merchant sloop was crawling upstream at a little more than a knot. Byrne was in luck. Had the tide been going out and the wind stronger, the current in the Southwest Pass at that time of year could have reached four knots, stopping the sloop in its tracks. The nine-hour pursuit covered less than 11 slow-motion miles, as the winds favored first one vessel and then the other. Bolivar eventually came within a “long musket shot” of Isabelle, seemingly about to catch the smaller ship. At 6 p.m., Byrne gambled, cutting inside the bend of the pass. His ship’s lesser draft cleared the shallows, but the deeper-hulled Bolivar ran aground in mud.

Byrne steered for the main channel, heading downstream to the Balise, a settlement near the mouth of Southeast Pass of the Mississippi. He was hoping to encounter Louisiana, the vicinity’s only federal revenue cutter, known to frequent the hamlet. Louisiana was there. Hearing Byrne’s tale, Captain John Jackson made ready to sail. Night had fallen. The 60-foot drop keel schooner—its keel, or weighted stabilizer, could be raised in shallow water—would be sailing against the big river’s current. A steam towboat, Post Boy, was at the dock. The captain offered to muscle Louisiana upstream. Jackson accepted. Byrne boarded the cutter to lead Jackson to the spot where the privateer had grounded itself. Lashed side by side to Louisiana, Post Boy powered upstream against the current. The going was slow. When, shortly after turning downstream into the Southwest Pass, the vessels shot by Bolivar’s armed boat toiling in the other direction, Jackson’s crew let the outlaws be, pending a return trip.

Three miles down the pass, Bolivar was floating at anchor. Grounding had disabled the privateer’s rudder. With the cutter’s two 4-lb. guns and four 18-lb. carronades covering the helpless pirate, a boarding party led by First Lieutenant E. L. Petit collected Bolivar’s papers and brought Chicot aboard the cutter for questioning. Jackson had Petit arrest the officers and crew and seize Bolivar on suspicion of piratical activity. The suspects did not resist. Finding an officer and three crewmen from Antoinette imprisoned aboard the pirate alerted Jackson that the seized vessel likely was nearby.

Taking Bolivar in tow, Post Boy and Louisiana headed for New Orleans, on the way meeting the outlaw boat, whose 13 occupants brought the arrest roster to 33. Authorities in New Orleans arraigned and jailed the prisoners, also issuing a warrant charging Bolivar’s owner, François Reibaud, with piracy.

A search by Louisiana for Antoinette turned up nothing. The cutter left for New Orleans for repairs but word spread among pilots and ships’ captains to keep an eye out for the missing vessel.

The morning of May 18, Antoinette was heading into the anchorage at the Southwest Pass when Captain Samuel Harriston of the tow steamer Favorite and a pilot boat’s crew spotted the vessel. Harriston sailed upstream to Fort St. Philip to get help from the U.S. Army garrison there. The pilot boat went alongside Antoinette to investigate. Slipping away without the prize crew noticing, Captain Bateman climbed into the pilot boat and huddled with the pilots, who realized the pirates had no idea that the authorities had their shipmates in custody. The pirate prize master appeared at the rail brandishing a musket. At gunpoint, he ordered Bateman back aboard and the pilot boat to shove off. Antoinette sailed nearer shore and anchored among ships waiting there. Low on provisions, the prize crew sent a boat to a nearby brig to buy bread. Junior river pilots told their boss, Charles Matthews, about Antoinette. Matthews improvised a plan. He sent his men to the pilot station to arm themselves with muskets, then go about their business, keeping a close watch on Antoinette while he boarded the seized vessel and tried to convince the prize master that Chicot had hired him to guide the ship upstream to Bolivar for reprovisioning. Once Matthews had the wheel, he would ground Antoinette, distracting the pirates so the armed pilots could swarm aboard.

Around 2 p.m., Matthews, in a pilot boat with a crew of three, approached Antoinette. Going aboard, he spun his tale with complete success. The pirates raised anchor and got underway. Bateman whispered to Matthews that they should try to grab the vessel. Matthews told him to wait. As planned, Matthews grounded Antoinette. He assured his clients that the tide would free the ship, but the pirates did not want to wait. They launched a boat with three men to drop a kedge anchor, a tool for moving vessels in tight quarters. By attaching the kedge anchor to a ship’s windlass, rowing a distance, and dropping the anchor, a crew could manhandle a vessel into or out of place. Intent on their efforts, the men of the prize crew ignored the four armed pilots scrambling over the seized ship’s bow. The pilots subdued and rounded up the pirates.

With two of his crewmen and the pilots, Bateman refloated Antoinette and set sail for New Orleans. Night was falling and the wind slackening when he encountered Favorite with 20 soldiers from Fort St. Philip hidden onboard. As a ruse to get alongside the other ship, Harriston offered to take Antoinette in tow. Instead, Bateman decided to anchor overnight, planning to resume sailing at first light. He and his men confined the pirates to the forecastle under guard; any man coming aft of the mainmast would be shot. Favorite anchored nearby.

In the morning, before Bateman could hoist anchor, Favorite came alongside and disgorged an armed boarding party led by Lieutenant William Lee Morris. The soldiers overpowered Bateman, his crew, and the pilots. Bateman tried to explain the situation, proffering the ship’s papers. A skeptical Morris told the ship’s master to shut up or be clapped into irons. Favorite towed Antoinette to the fort, where a customs officer identified Bateman and the pilots and ordered their release. Favorite transported Antoinette and the pirates under army guard to New Orleans, where the outlaws joined their jailed compatriots.

Despite a lack of fatalities or injuries, a federal court convicted the officers and crew of Bolivar of piracy. August Chicot drew four years; officers, three; petty officers, two. Ordinary seamen got a year behind bars, save for an ill man who only did three months. Because Captain Reibaud could prove he had been in New Orleans and Mobile during the episode, charges against him were dismissed. Continuing the contretemps that had begun aboard Antoinette, Morris claimed he thought Bateman a pirate; Bateman accused the Army man of trying to horn in on the revenues from salvaging his ship.

Bolivar was auctioned, the proceeds going to Captain Jackson of Louisiana for his part in the privateer’s capture. The admiralty court ordered Antoinette sold to satisfy the claims of those who had recovered her—$1,000 to Charles Matthews, $1,500 split among the other pilots. A claim by the U.S. Army was dismissed. That Bateman pressed no claim at first puzzled observers; however, it came to light that claims against the loss of the vessel and its cargo had been paid by Niagara Insurance and American Insurance to its owner and Bateman. The War of 1812’s piratical legacy sputtered on in the Gulf for a decade, finally stamped out by Revenue Cutter Service and Navy patrols and admiralty juries’ newfound willingness to return guilty verdicts.