One day in 1856, residents of Fairfield, Iowa, scowled at an 18-year-old farm girl with curly dark hair who was parading around the muddy town square wearing loose “Turkish” pants, popularly known as bloomers. Rebecca Ilgenfritz, ignoring the raised eyebrows and horrified guffaws that followed her along the uneven wooden sidewalks, flaunted her comfortable two-legged pants and calmly nodded at passersby. Rebecca’s bloomers caused such a stir that day that nearly 80 years later Dr. J. F. Clarke, a Fairfield physician and onetime mayor, saw fit to mention the episode in his memoirs of the pioneer doctors of Iowa’s Jefferson County.

Rebecca knew early on she was going to be someone remarkable. Her self-confidence prompted her to show off in the most public way she could think of as a teenager, and her thick skin allowed her to handle any criticism that followed. These qualities served her well when, as “Mrs. Dr. Rebecca Jane Keck,” she defied convention and the legal standards of the powerful medical establishment in the upper Mississippi River valley to preside for nearly 30 years (1873–1900) over a patent medicine business serving up to 15,000 customers in Iowa and Illinois.

Born in Wooster, Wayne County, Ohio, on February 7, 1838, into a Pennsylvania Dutch pioneer family, Rebecca immigrated to Iowa with her family at age 13. She passed her teen years on a small, struggling farm in the Hardscrabble section of Fairfield Township and shared the responsibility of caring for her nine younger siblings. No records survive, but possibly she completed seven or eight years of elementary schooling.

Either because or in spite of her notoriety following the 1856 bloomer incident, Rebecca met and married a tall, bearded 29-year-old merchant/mechanic named John Conrad Keck in January 1857. For the first 13 years of their marriage, the couple did not stand out from the crowd of young families in Fairfield. According to her own promotional materials, Rebecca and several of her six children (five daughters and one son) suffered from severe lung disease during these years, and she collected herbs and brewed up medications to cure their “catarrh,” a 19th-century catchall term for everything from asthma to consumption.

Meanwhile, Rebecca’s husband, who aspired to invent farm machinery, opened a small foundry in 1866. The business took off quickly. By 1871, the Kecks owned four plots of land and a burgeoning machine shop that employed 15 men. They were riding high until the national banking Panic of 1873 choked off the money supply in September, and people could not afford expensive farm machinery. Rebecca immediately stepped in to help support the family. Not for nothing had John married a girl willing to wear bloomers in the town square. As his foundry business fell apart, John joined Rebecca along the roadside to harvest the herbs needed for her catarrh tonic.

In November 1873, with John’s full support, Rebecca took the train to Dubuque, Iowa. She ran a small ad in The Dubuque Herald for Keck’s Catarrhochesis and rented a room from a Miss Eggleston on Clay Street for a week to see new patients. From this modest start, she began selling her alcohol-based kidney tonics and bitters to the wider public.

Within six months she was running her newspaper ads in other Iowa cities, including Fairfield and Davenport, and printing testimonial letters from satisfied patients as references. One of her early ads compared her miraculous treatments to the equally miraculous “water-fueled” Keely Motor, which was a sensation at Philadelphia’s Centennial International Exposition of 1876 but later proved an ingenious fraud. In an era before medical associations had established any professional credentials or educational standards, Keck was legally allowed to declare herself a physician in her advertising. As business boomed, she adopted the public persona “Mrs. Dr. Keck, the Celebrated Catarrh and Consumption Specialist.”

By early 1876 Keck had moved her family and practice to Davenport, establishing an office at which to see patients and from which to sell her remedies. By then she was placing newspaper advertisements in such Illinois cities as Peoria, Bloomington, Quincy and Champaign. ATTENTION! began one such ad in the Bloomington Leader:

YOU HAVE READ WHAT THE PEOPLE SAY, NOW PERUSE WITH CARE THE OPINIONS OF THE PRESS.…MRS. DR. KECK GIVES HER LIFE, HER ENTIRE TIME AND LABOR, TO THE GRAND CONQUEST OF HUMAN DISEASE… BY VIRTUE OF RARE MERIT, SUPPORTED BY INDOMITABLE PERSEVERANCE, [SHE] HAS WORKED HEROICLY [SIC] AND RAPIDLY UPWARD UNTIL NOW SHE STANDS UPON AN EMINENCE, PROFESSIONALY [SIC] CELEBRATED, SOCIALLY RESPECTED AND FINANCIALLY SOLID… CAPABLE OF DOING THE WORK OF FIVE ORDINARY WOMEN…A GREATER CELEBRITY THAN ANY FEMALE PHYSICIAN IN THE WEST.”

She boasted in her ads of providing “MOST REMARKABLE CURES: NOT A SINGLE CAUSE LOST”—and not just for catarrh, but also for everything from insanity to heart disease to female problems.

Mrs. Dr. Keck consulted with customers in rented rooms and hotels as she traveled her regular circuit while serving other customers through assistants in “branch offices” and by mail order. Her three oldest daughters, Belle, Lotta and Flora, became business managers. Even her husband, the mechanic and former foundry owner, began calling himself a doctor and introduced his own product to the public—Dr. J.C. Keck’s Pile Remedy.

Passage of the Illinois Medical Practice Act of 1877 heralded the medical profession’s struggle to establish licensing standards. Properly trained doctors wanted to eliminate the quacks and irregular physicians from their ranks and to force medical schools to train new doctors in scientific methods. Wealthy and popular Mrs. Dr. Keck, who called herself a physician even though she lacked formal training or credentials, became an outspoken opponent of the new Board of Health in Illinois, as well as of the county medical societies in Iowa, where statewide legal standards for medical practitioners were more lax. In February 1878 the Bloomington Leader warned, “A test case will probably be made of the new law governing physicians in this state.” It reported that the president of the Board of Health had threatened “to cut loose the dogs of war to compel Mrs. Keck to produce her diploma,” which she didn’t have.

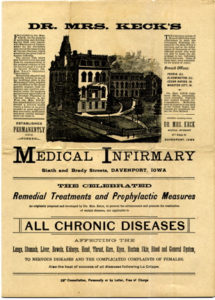

But the specter of legal action didn’t dissuade Mrs. Dr. Keck—indeed, she defiantly expanded her business in a spectacular way. In June 1879 the Davenport Daily Gazette reported that this “energetic and able lady” purchased the old Cook mansion, a huge property at 611 Brady St. in Davenport, for $12,000, “a low figure.” One of Keck’s most determined opponents, Dr. Edward H. Hazen, had been leasing the mansion for his eye and ear clinic and residence. Keck had Dr. Hazen and his family evicted, hired her brother-in-law to quickly redecorate the mansion and in two weeks opened Mrs. Dr. Keck’s Infirmary for All Chronic Diseases.

Her business hit its greatest heights over the next five years, even as Dr. John Rauch, secretary of the Illinois State Board of Health, fumed that Mrs. Dr. Keck and several other itinerant physicians were “blots and stains and foul and damnable in every way.” It was up to local medical societies to prosecute itinerant practitioners and those deemed quacks—an expensive, time-consuming and unpopular task. Mrs. Dr. Keck appeared in court with her attorney, W.S. Coy, at least five times in Illinois during the early 1880s. She paid large fines but continued to practice, advertise and sell her remedies. Sometimes her temper flared up—in Peoria she countersued Dr. O.B. Will for $10,000 for trespass on her lease, although her lawyer quietly let the case drop by failing to file some procedural papers.

Mrs. Dr. Keck and the state of Illinois wore each other down to a Mexican standoff. Rebecca’s prodigious workload took its toll on her health, and she settled into a well-worn groove as she got older— avoiding places like Decatur, Ill., where hot-tempered, hard-line local medical authorities made it difficult to operate but reaping a steady income in less-hostile Illinois cities like Peoria and Bloomington.

Eventually, the tide of public confidence turned away from patent medicines, and in 1900 Mrs. Dr. Keck retired with her loyal husband to Chicago and sold her infirmary. Her three older daughters had veered off from the family business into real estate speculation in Chicago’s Jackson Park, site of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In any case, the era of seat-of-the-pants medical advice by mail had passed. After blanketing the Midwest with many thousands of advertisements for almost three decades, Mrs. Dr. Keck soon faded from people’s memory. Rebecca died in 1904 at age 66, and her husband followed her to the grave in 1911.

A notorious quack she might well have been, but Mrs. Dr. Keck “cured” her share of patients, and many contemporaries saw her career in medicine as groundbreaking for women. Editors of The Decatur (Ill.) Morning Review wrote in November 1883: “LADY PHYSICIANS— We have a marked example among us of female success in medicine, in the person of Mrs. Dr. Keck, well-known in the West.” The Bloomington (Ill.) Pantagraph had this to add: “The rapid and substantial progress which is being made in her professional career by Dr. Mrs. Keck of Davenport Iowa…is a subject for congratulation among the women of America… a forcible illustration of the ability of women to succeed.”

Greta Nettleton of Palisades, N.Y., is writing a book called The Charmed Line, about the life of Mrs. Dr. Rebecca J. Keck and the origins of alternative medical care in 19th-century America. The author [gretan@optonline.net] would love to hear from any readers with information about Mrs. Dr. Keck and/or labels from the medication she sold.

Originally published in the April 2012 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.