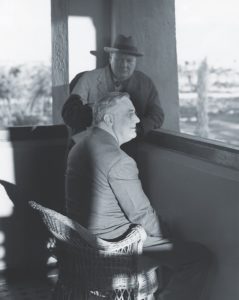

In the early hours of May 10, 1940, as German soldiers surged forward into Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg, Britain’s Conservative Party leadership tapped Winston Churchill, 65, to become their country’s next prime minister. For the unruly black sheep of Parliament, it was a stunning turnaround. Churchill had spent much of the 1930s in what he called “the wilderness”—a political exile of his own making. Now the pugnacious personality that had long sidelined Churchill became one of England’s most valued assets.

After warning of the German threat for nearly a decade, Churchill understood more acutely than most that “the nations which went down fighting rose again, but those which surrendered tamely were finished.” Maddening at times, fierce and funny, savage but with a soft side, Churchill provided his nation with a singular focus as the dark cloud of Nazism descended over Europe. He was, say biographers William Manchester and Paul Reid, “a multifarious individual, including within one man a whole troupe of characters, some of them subversive of one another and none feigned.” Collectively those traits saw Britain through its darkest hour. ✯