“I was conscious of the Greek historian Thucydides’s prompt to write the history of which you are a part.”

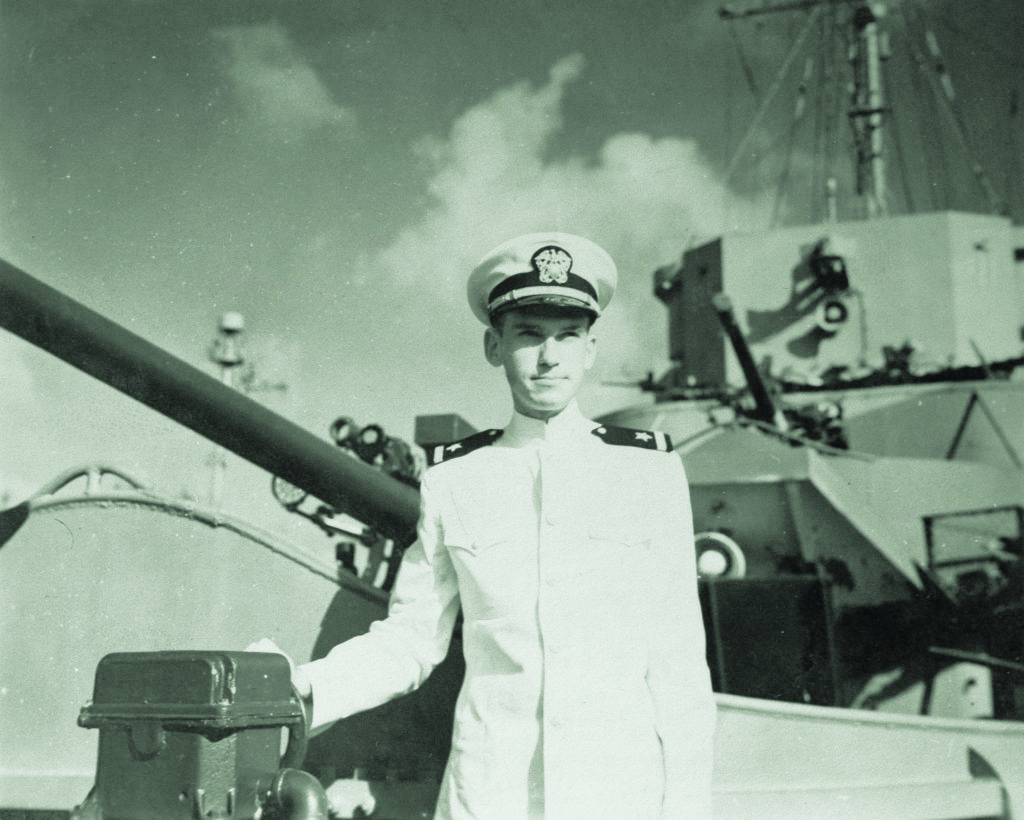

Philip K. B. Lundeberg was a 22-year-old ensign when a U-boat torpedoed his ship, destroyer escort USS Frederick C. Davis. It was the last U.S. Navy warship lost in the Battle of the Atlantic. Only three officers and 74 sailors from a crew of 192 survived. The experience proved seminal for the budding historian. Studying at Harvard after the war, Lundeberg collaborated with historian (and rear admiral) Samuel Eliot Morison on a book in Morison’s classic 15-volume History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Lundeberg went on to teach at Minnesota’s St. Olaf College and at Annapolis before joining the Smithsonian as its curator of armed forces history. A curator emeritus at age 96, Lundeberg reflects here on cheating death to launch a career “teaching millions about American naval history.” He died on October 3, 2019, as World War II‘s February 2020 issue was being completed.

What was your preparation for serving aboard Frederick C. Davis?

While I was an undergraduate at Duke University, I went into the U.S. Navy V-12 College Training Program. I graduated Duke in February of ’44, then got orders to New York Naval Reserve Midshipmen’s School at Columbia University. I was there for four months, studying when I should have been eating in order to get through.

After midshipmen’s school, I was sent to Miami, to the Sub Chaser Training Center, and then to the Fleet Sonar School in Key West. I went aboard Frederick C. Davis at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in November of ’44. I discovered—typical of Navy experience—they already had a sonar officer, so I ended up being assistant first lieutenant and damage control officer. Its crew was a gung-ho group. The people I worked with were the rugged boys of the deck force, known as “deck apes.” The engineers were “snipes”; the people in communications were “bridge pussies.”

What was the ship’s mission when it was attacked?

The ship had returned stateside in September ’44 after heavy fighting in the Mediterranean. There had been newspaper reports about the threat of German rocket missile attacks on New York—vengeance attacks; New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia warned his citizens about this. The U.S. Navy said the attacks could come from long-range aircraft or from disguised merchant ships or submarines.

The navy laid on “Operation Teardrop.” This involved two huge barrier groups positioned north to south across Atlantic sea-lanes. Each consisted of 20 destroyer escorts and two escort carriers to intercept suspected U-boats coming from Norway.

The Germans had dispatched nine U-boats, in the latest—and final—iteration of “Operation Seewolf”: not a rocket mission but an effort to reestablish the U-boat offensive in American waters. Three U-boats had already been sunk when we encountered U-546 in the mid-Atlantic, northwest of the Azores, on April 24, 1945.

Where were you during the attack?

I had been on watch the previous night, and we’d been receiving radar and sonar contacts indicating sub activity in the vicinity. After my watch, I went down to the wardroom and slept on the couch. My friend Bob Minerd, a classmate at Columbia, said: “Phil, why don’t you go back aft and get some real sleep?” I did and was sleeping directly over the ship’s screws [propellers], which is where the torpedo—an acoustic, sound-homing torpedo—normally would have hit.

Why didn’t it?

Well, our ship had come around to investigate this particular sound contact. The torpedo headed for the screws, but because the boat turned, it hit midships. The ship jackknifed. There were three of us in the after officers’ quarters; two of us survived. Bob Minerd was the only officer up forward who made it.

What did you do next?

I started trying to dog down watertight doors and checked depth charges to make sure they wouldn’t explode. The ship’s decks were soon awash. When I abandoned ship, I literally walked into the water. I managed to get out to a life raft. We had a lot of injured people. Nobody sat; you’re holding onto loops on the side of the raft, and you’re lucky to have your head out of the water. A couple of the depth charges went off and everybody got a blast up their rectum. We were in 40-degree water for about two hours, most of us in shock.

The other ships in the barrier group had to deal with the U-boat before rescuing us. It turned out there was a second U-boat in the area; if that U-boat had been as aggressive as U-546, none of us would have been picked up. I was finally rescued by the destroyer escort USS Hayter. We survivors were taken back, ultimately, to Boston.

So, you lived some momentous history before studying, writing, and teaching it.

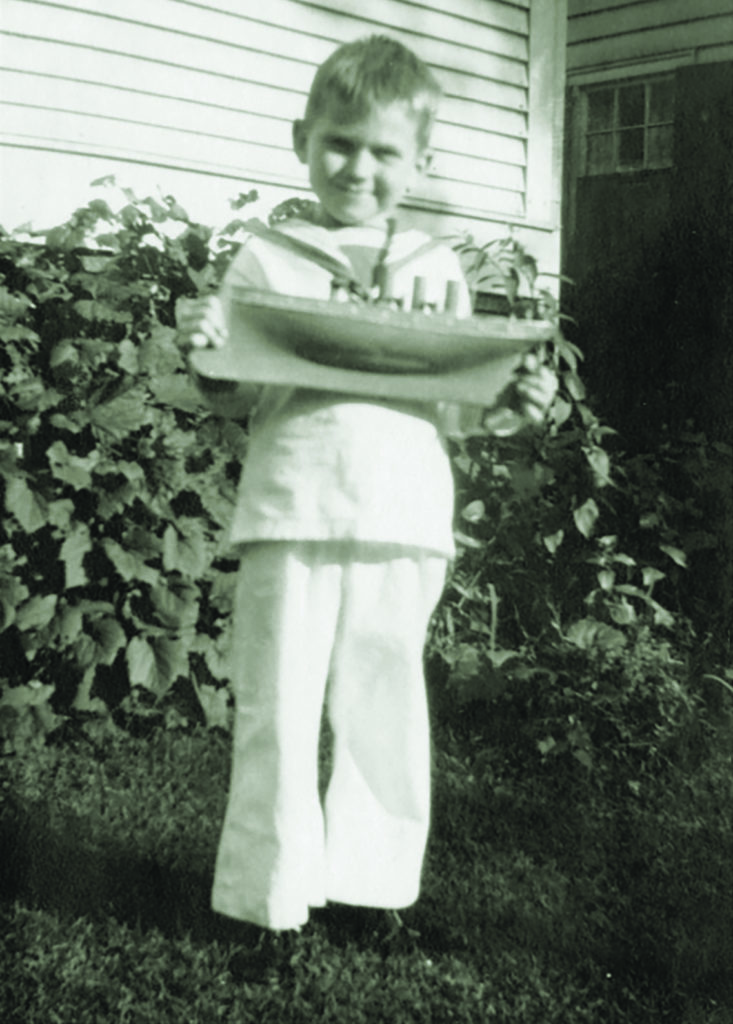

Yes—but I also grew up on the academic circuit. My father, Olav Knutson Lundeberg, was a teacher of Romance languages. In 1931, he was called down to Duke University, and he spent the rest of his career teaching there.

I was very fortunate being at Duke. I came out of the service and went back to Duke for graduate school. I completed a master’s degree in history and ended up going to Harvard for a doctoral program. The historian Samuel Eliot Morison, who had returned to teaching there after serving in the navy, liked a paper I did on naval engagements off the Chesapeake Bay in 1779 and 1781. I was still in the Navy Reserve, so I asked if I could have two weeks’ duty in his office in Washington to do a monograph on Operation Teardrop.

His staff liked the study so much they persuaded me that I should do my dissertation on the latter half of the Battle of the Atlantic. I had taken German at Duke and Harvard; I did the detailed research that would end up in Morison’s series in Volume X: The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943-May 1945. I worked as someone who had survived and had information as a participant. I was conscious of the Greek historian Thucydides’s prompt to write the history of which you are a part.

What was your impression of Morison?

Morison was one of the most amazing American historians we had in the last century—a tremendously prolific historian and writer. I had interesting experiences with him. For example, in concluding Volume X, Morison came up with the characterization that Hitler’s navy died with a whine and a whimper. I said, “Wait a minute. Admiral, the German navy in World War II that I encountered was fighting to the bitter end, even knowing that the war was over.” He accepted that and came up with a more felicitous assessment.

What was your direction after Harvard?

I realized that I should be doing naval history, so I joined the faculty of the Naval Academy. I enjoyed teaching midshipmen a great deal because they were well-rounded young people. Eventually, I got word from Morison’s assistant that Morison thought I should pursue a job in naval history at the Smithsonian. That was in early 1959. The idea of doing armed forces history in a national historical museum appealed to me. Fortunately, I came into a staff that was made up entirely of people who had been in military service. We had a basis of appreciation for our subject that was personal, which made for a unique camaraderie.

From a historian’s perspective, how do you reflect on your experience aboard Frederick C. Davis 75 years ago?

The sinking of my ship is an example of what I call a microhistory: the documented experience of survivors of a “terminal” event like the sinking of a ship or the wiping out of a battalion. Survivor interviews and memoirs create a core of information that captures the popular imagination. But they also create questions, new angles, new sources, new insights for historians. They help achieve understanding. ✯

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of World War II.