[divider_flat]Maj. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs designed the project to be both functional and awe-inspiring

[divider_flat]ON A FRIGID MID-DECEMBER DAY IN 1914, John Greenawalt had finally mustered the energy to return to work. At 74 years old, Greenawalt was the principal examiner and reviewer for the U.S. Pension Bureau, located in a massive red-brick building in downtown Washington, D.C.

Greenawalt had spent the previous two weeks at home with an illness, but decided he was well enough to return to the business of helping Civil War veterans and their families claim their pensions. After all, he knew what they had gone through. A Pennsylvania native who’d joined an Iowa regiment, Greenawalt had been wounded in the groin and thigh at Fort Donelson, Tenn., in 1862, but he’d survived to have a long, fruitful career.

Just two days after returning from sick leave, however, Greenawalt slumped over at work and was gone. Greenawalt’s family took comfort in knowing that he died serving his fellow soldiers to the last. After the Civil War, the massive outpouring of claims filed by veterans—and their widows and children—prompted the U.S. government to commission a new Pension Bureau building large enough to manage the more than 1,500 clerks and many tons of paperwork the task required. Only one man seemed tailor-made for the job: Maj. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, the quartermaster general of the Union Army and a West Point–trained civil engineer and architect. Meigs had been responsible for major improvement projects around the nation’s capital in the two decades after Appomattox, most notably the development of Arlington National Cemetery and the Washington Aqueduct. Although he didn’t know it at the time, the Pension Building would be Meigs’ last commission, and one of his greatest legacies.

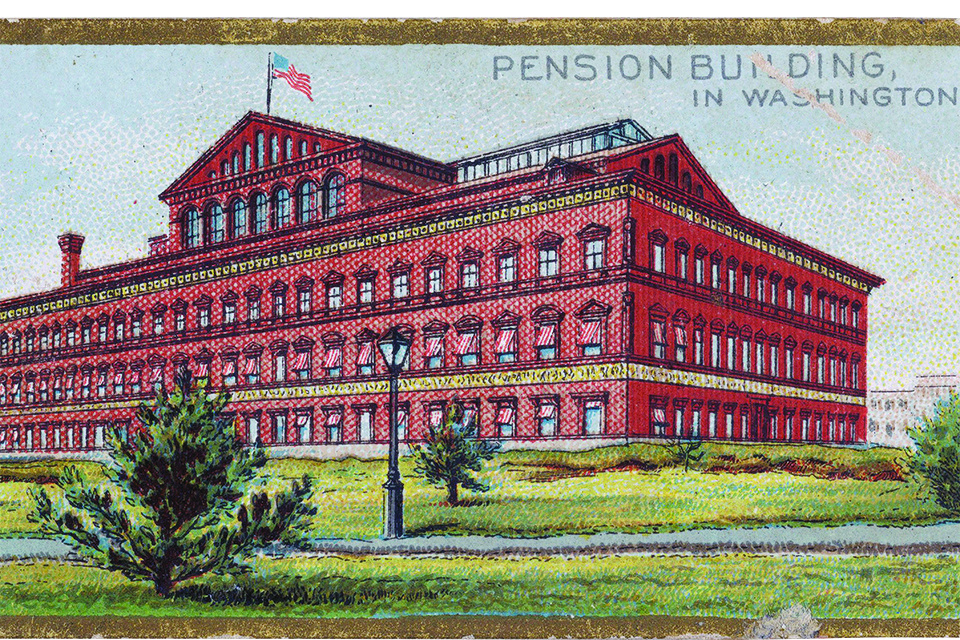

Inspired by the 16th-century Farnese Palace in Rome, Meigs designed the new Pension Bureau building in the Italian Renaissance style, a break with the neoclassical architecture that characterized downtown Washington. Yet Meigs wanted the Pension Bureau to have a commanding presence, too—to be both functional and awe-inspiring, a monument to the soldiers he’d served alongside. Instead of white marble, the three-story rectangular building, crowned with a gabled clerestory, is built from industrial red brick. Meigs hired workers at the rate of $4 a day, who mortared and placed some 15 million bricks in all between 1882 and the building’s completion in 1887.

Inside the Pension Bureau building, still in use as the National Building Museum, an expansive central atrium is dominated by eight colossal Corinthian columns, each over 75 feet tall with an eight-foot-diameter base, and made from some 55,000 bricks. Around the perimeter, open arcaded galleries lead to various offices. Entrances on each of the four sides lead to wide staircases with low treads, which Meigs figured would be easier for injured veterans to navigate. On the third floor, builders installed a metal track to help transport documents around the building (along with a dumbwaiter), and a smaller fourth floor was devoted to document storage, undergirded with beams for support. ¶

Critics savaged the unusual structure, giving it the nickname “Meigs’ Red Barn.” Oft-repeated legend has it that either General Philip Sheridan or William T. Sherman said, “Too bad the damn thing is fireproof.” Even years later, the McMillan Commission called the building a “regrettable deviation from the classical precedents of the Founding Fathers.” Yet Meigs was steadfast in defense of his choices: “Those who live in it appear to be content with it, and I believe that its continued use will justify the theory of its design and construction. No dark, ill ventilated corridors depreciate the health of those who work in it or depress their spirits. Every working room is lighted from windows on two sides. There is not a dark corner in the building.”

For all the Pension Bureau building’s interior light and magnitude, its most notable exterior feature is only three feet tall: a bas-relief frieze of Civil War soldiers and sailors, inspired by the frieze at the Parthenon, which runs continuously along its 1,200-foot perimeter. “This frieze will be the most important and conspicuous decoration on the exterior of the building,” Meigs wrote. “If it is so done as to please, it will be very much admired; if it is faulty, the press will cover it with ridicule.”

For this, Meigs turned to sculptor Caspar Buberl. Born in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), Buberl had emigrated to America in the 1850s and established a popular sculpture studio in New York City by the early 1870s. Meigs’ original choice for the sculpture design had been the Boston Terra Cotta Company (which would manufacture the terra cotta panels), but after receiving the company’s initial mock-ups, he wrote to Buberl saying, “I think you can do better.” Buberl and Meigs agreed to a design in which scenes of infantry, cavalry, artillery, and sailors, as well as a quartermaster, medical personnel, and a black teamster—whom Meigs insisted “must be a negro, a plantation slave, freed by war”—would proceed around the building. The repetition helped the project to be economical, but the frieze’s sheer length helped the repetition to not be overly noticeable.

Despite the criticisms the overall building received, the frieze was widely praised. “Many a veteran feels his pulse quicken as he beholds the details of the frieze, reviving never-to-be-forgotten scenes in the great Civil War,” wrote one Washington memoirist. The frieze’s soldiers “are not the stereotyped soldiers and sailors of the picture books,” wrote a reviewer for The Century Illustrated Magazine, “but seem to have been designed by someone who has seen actual warfare.” Buberl had not, but Meigs had, including losing a son in 1864.

The Pension Bureau operated in the building for 40 years. During that time, $8.3 billion was paid to nearly 2.8 million veterans and their families. The lavish interior was also the site of several inaugural balls, beginning with Grover Cleveland’s first inaugural in 1885, when a temporary wooden roof covered the still-incomplete building. Eleven other presidents held balls or parties there as well, including Presidents McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, and most recently Obama.

By the 1920s, as the Civil War generation was passing into history and the number of claims lessened dramatically, the Pension Bureau merged into the Veterans Administration. The General Accounting Office took over the building in 1926, followed by a succession of other federal agencies through the 1970s.

Meigs died of pneumonia in 1891, having seen his last commission through completion. Nearly a century later, the building became the permanent home of the National Building Museum in 1985. In addition to hosting exhibitions about architecture and placemaking, the museum maintains an archive of architectural blueprints, models, and artifacts, including a tea set given to Meigs by some of his former staff, several old workers’ shoes found over the years during maintenance, and a portion of a wooden beam signed by the quartermaster general himself.

The most important artifact, however, is undoubtedly the building itself, now a designated national historic landmark. To this day, only a few miles from where both Montgomery Meigs and John Greenawalt are buried in Arlington National Cemetery, those terra cotta soldiers are still marching around the red barn, an idealized version of all the broken men Meigs had sought to honor and help.

Kim O’Connell is a writer based in Arlington, Va., who has degrees in both literature and historic preservation. She is drawn to places like the old Pension Building, where the imprint of the people who inhabited them is still palpable.