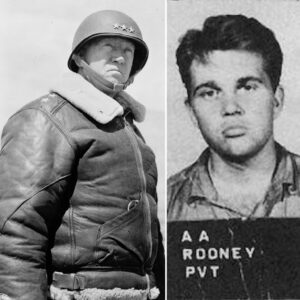

In 1952 the widow of George S. Patton Jr. provided an intimate glimpse into the legendary general’s thinking.

It began with the classics, for the Pattons felt that life was too short to get one’s education unless one started early, and the family loved to read aloud. By the time the future general had reached age eight, he had heard and acted out The Illiad, The Odyssey, some of Shakespeare’s historical plays, and such books of adventure as The Scottish Chiefs, Conan Doyle’s Sir Nigel, The White Company, The Exploits and Adventures of Brigadier Gerard, The Boy’s King Arthur, and the complete works of G. A. Henty.

As a cadet he singled out the great commanders of history for his study, and I have his little notebook filled with military maxims, some signed J. C., some Nap, and some simply G. Sources were his specialty, and as a bride, I remember him handing me a copy of von Treitschke, saying: “Try and make me a workable translation of this. That book of von Bernhardi’s, Germany and the Next War, is nothing but a digest of this one. I hate digests.” Unfortunately, my German is not of that caliber, and he had to make do until a proper translation was published several years later. He was, however, one of the first Americans to own that translation, as later he owned translations of Marx, Lenin, and the first edition of Mein Kampf—believing that one can only understand Man through his own works and not from what others think he thinks. No matter where we moved, there was never enough room for the books. We were indeed lucky that an army officer’s professional library is transported free.

He made notes on all the important books he read, both in the books themselves and on reference cards, and he was as deeply interested in some of the unsuccessful campaigns, trying to ferret out the secret of their unsuccess, as he was in the successful ones. I have one entire book of notes on the Gallipoli campaign. He was especially interested in landing operations, expecting to make them himself someday.

Our library holds many works on horsemanship, foxhunting, polo, and sailing, all sports with a spice of danger to keep a soldier on his toes in time of peace. He was an intensive student of the Civil War, and one of his regrets was that his favorite military biography of that period was a foreigner…G. F. R. Henderson’s Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War. Imagine his delight when Douglas Southall Freeman’s Lee began to appear. He bought and read them one volume at a time, and when I showed it to the author, crammed with my husband’s notes and comments, he smiled: “He REALLY read it, bless his heart.” His memory was phenomenal and he could recite entire pages from such widely different sources as the Book of Common Prayer, Caesar’s Commentaries, and Kipling’s and Macaulay’s poems. On the voyage to Africa in 1942, he read the Koran, better to understand the Moroccans, and during the Sicilian campaign, he bought and read every book he could find on the history of that island, sending them home to me when he had finished them.

During the campaigns of ’44 and ’45, he carried with him a Bible, prayer book, Caesar’s Commentaries, and a complete set of Kipling—for relaxation. A minister who interviewed him during that winter remarked that when he saw a Bible on his table, he thought it had been put there to impress the clergy, but had to admit later that the general was better acquainted with what lay between the covers than the minister himself.

Most of all, he was interested in the practical application of his studies to the actual terrain, and as far back as 1913, during the tour at the French Cavalry School, we personally reconnoitered the Normandy Bocage country, using only the watershed roads used in William the Conqueror’s time, passable in any weather. When he entered the war four years later, he fought in eastern France, but in 1944, his memory held good. People have asked me how he “guessed” so luckily.

“Terrain is sometimes responsible for final windup of a campaign, as in the life of Hannibal,” he wrote. To him, it was not a coincidence that the final German defeat in Africa was near the field of Zama. His letter, “I entered Trier by the same gate Labienus used and I could almost smell the sweat and dust of the marching legions,” is an example of how dramatically he could link the present with the past. As he had acted out the death of Ajax on the old home ranch, so he and our family acted out Bull Run, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. I have represented everything in those battles from artillery horses at Sudley’s Ford to Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing, Army of the Potomac, at the battle of Gettysburg. That was a battle long to be remembered. At the end of the third day, as the girls jumped over the stone wall into Harper’s Woods, Ruth Ellen fell wounded, took a pencil and paper from her pocket, and wrote her dying message. (The original by Colonel Waller Tazewell Patton, C.S.A., is in the Richmond Museum.) I heard a sort of groan behind me. As Lieutenant Cushing, firing my last shot from my last gun, I had been too busy to notice a sightseeing bus had drawn up and was watching the tragedy of Pickett’s Charge.

If I have digressed from my subject, reading, it is to show the results of reading. First he studied the battles; then, when possible, played them out on the ground in a way no one who ever participated in the game can forget.

From his reading of history, he believed that no defensive action is ever truly successful. He once asked me to look up a successful defensive action…any successful one. I found three, but they were all Pyrrhic victories. History seasoned with imagination and applied to the problem in hand was his hobby, and he deplored the fact that it is so little taught in our schools, for he felt that the study of man is Man, and that the present is built upon the past.

As I read the books coming out of this last war, I know those that he would choose: authoritative biographies and personal memoirs of the writer, whether he be friend or enemy. No digests!

Mrs. Patton’s Annotated List

Maxims of Frederick the Great

Napoleon’s Maxims of War, and all the authoritative military biographies of Napoleon, such as those by Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne and William Milligan Sloane.

Caesar’s Commentaries, Julius Caesar

Treatises by Heinrich von Treitschke, Carl von Clauswitz, Alfred von Schlieffen, Hans von Seeckt, Baron Antoine-Henri De Jomini, and other Napoleonic writers

The Memoirs of Baron de Marbot, a colonel under Napoleon. We were translating the latter when he went to war in 1942.

The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, Edward Shepherd Creasy

Charles XII—King of Sweden, Carl Klingspor

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon

Maurice’s Strategikon, George T. Dennis

The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli

The Art of War in the Middle Ages, Charles Oman, and other books by him

The Influence of Sea Power on History, A. T. Mahan, and other books by him

Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War, G. F. R. Henderson

Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, and those of George B. McClellan

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Robert Underwood and Clarence Clough Buel Johnson

R. E. Lee: A Biography and Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command, Douglas Southall Freeman

Years of Endurance and Years of Victory, Arthur Bryant

Gallipoli Diary, Sir Ian Hamilton

Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War

Memoirs of Erich Ludendorff, Marshal von Hindenburg, and

Ferdinand Foch

Genghis Khan, Alexander of Macedon, and other biographies, Harold Lamb

Alexander the Great, Arthur Weigall

The Home Book of Verse, in which he loved the heroic poems

Anything by Winston Churchill

Kipling, complete

Anything by B. H. Liddell Hart, with whom he often loved to differ

Anything by J. F. C. Fuller, especially Generalship: Its Diseases and Their Cure. He was so delighted with this that he sent a copy to his superior, a major general. It was never acknowledged. Later he gave 12 copies to friends, colonels only, remarking that prevention is better than cure.

Adapted from “A Soldier’s Reading,” by Beatrice Ayer Patton, which originally appeared in the November–December 1952 issue of Armor—The Magazine of Mobile Warfare.

[hr]

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.