Recommended for you

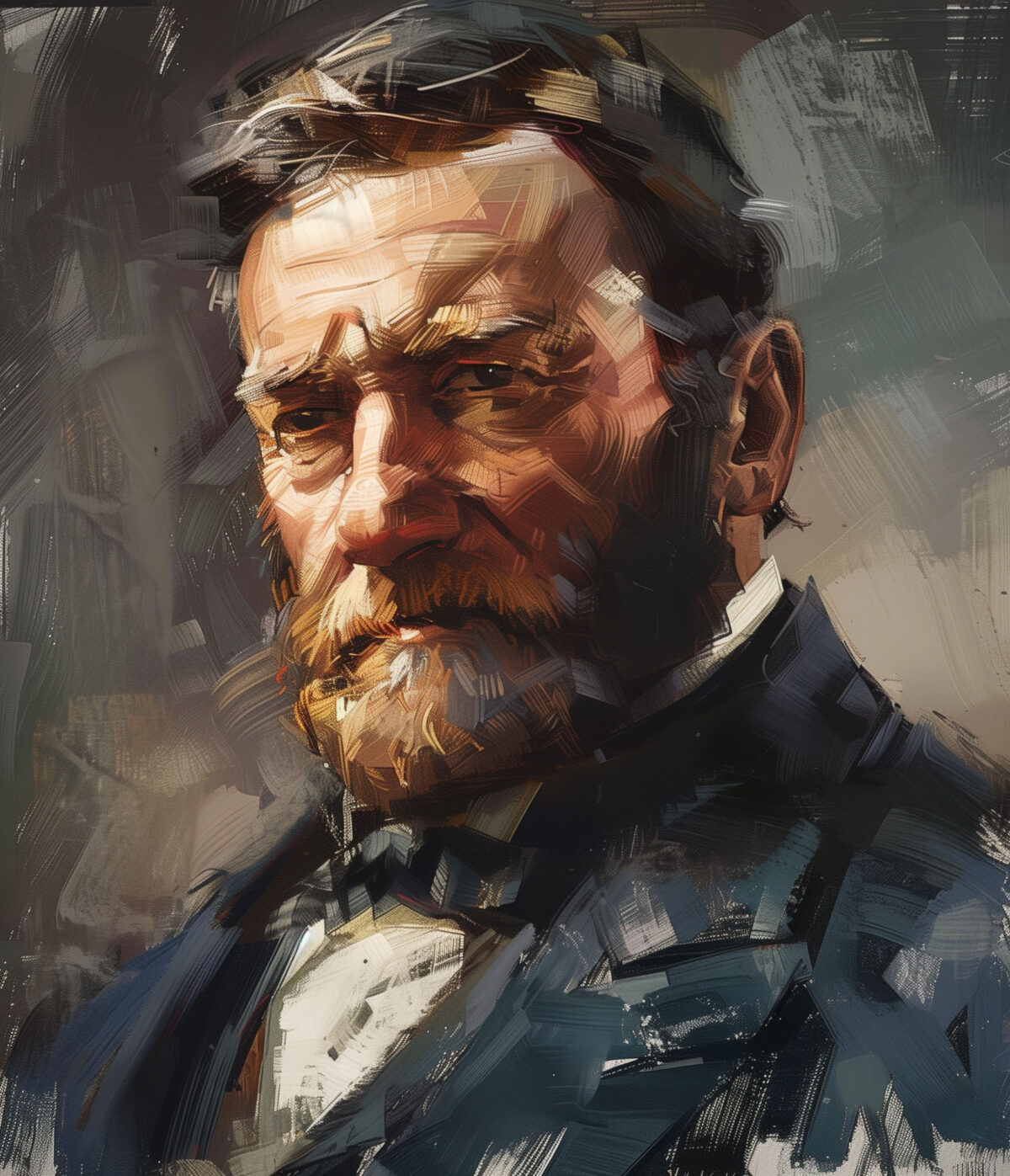

The sick, aging warrior put down his pen. It was July 18, 1885, and Ulysses S. Grant had just finished his memoirs. The hero of war had no way of knowing his final determined act would also make him a literary hero. In terrible pain from throat cancer, hour after hour and day after day he had pushed himself to write his recollections from his cottage atop New York’s Mount McGregor. He knew the end was near. “Man proposes and God disposes,” he wrote. “There are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice.”

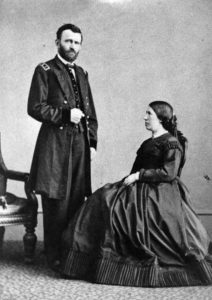

Grant wrote the memoir in part because he had lost all his money in a financial scandal and hoped the sales of the book would provide income for his wife, Julia, and their children. But the general and president also wanted the world to know his thoughts about the Civil War and his role in the conflict. The result of his death-defying determination was the creation of one of the greatest pieces of nonfiction in all of American literature, a memoir that dozens of historians have used as a source to produce studies of the war, and that uncounted people have read for personal enrichment. The publication of such a work would have been extraordinary even if it had been accomplished by a completely healthy man, much less one who was deathly ill.

Writing for the future

The contemporary readers of Grant’s memoirs had no problem understanding what he was saying and recognized the names mentioned in the book. After all, in the mid-1880s, the United States was still populated by people who had experienced the war. Most of the war’s veterans were about 40 years old, and their wives and families were similarly young. But in 2018, of course, all Civil War veterans are long gone, and the average reader has limited knowledge about what Grant was describing. Therefore, a modern version, edited to explain the details, was absolutely essential if this classic was to remain understandable to a wide audience. It was to that end that I, ably assisted by David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, began work on an annotated version of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

It was very important that the editors allow Grant to speak his mind and allow him, unencumbered, to express what he believed. After all, the memoirs emphasize Grant’s perspective. He said as much in his preface, “The comments are my own, and show how I saw the matters treated of whether others saw them in the same light or not.”

As the editorial team worked on the memoirs, certain passages stood out as emblematic of Grant’s personality and his blunt nature when it came to expressing his opinion. The determination he conveyed during the Civil War was evident during an instance when he described having to swim a swollen creek on horseback to be sure he proposed to his fiancée, Julia Dent, before he left for the Mexican War. After recalling the incident, he ruminated, “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go anywhere, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.” What an insight into Grant’s role in the Civil War and in the writing of his memoirs.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Nor did Grant hold back on political opinions, stating exactly what he believed. For example, regarding the Mexican War of 1846-48, in which he served as a junior officer just a few years past his West Point graduation, he wrote that “the occupation, separation and annexation, were, from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.”

When it came to the Civil War, once again he saw slavery’s dire role: “The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United States will have to be attributed to slavery.” Despite believing that slavery, which he disliked, was the cause of the war, he was initially not ready to become part of the military to end it. When his father decided that he wanted to send him to West Point in 1839 so that Grant could receive a free education, the 17-year-old rebelled. “But I won’t go,” Grant insisted. His father stood firm, Grant recalled. “He thought I would, and I thought so too, if he did.” Even when he arrived at the military academy, Grant remained unhappy. “A military life had no charms for me,” he insisted.

Grant also harbored anti-military feelings, even when he reentered the army to fight in the Civil War. He was frightened of battle, especially leading men into combat. When Captain Grant took command of the 21st Illinois Infantry in 1861, he once again came face to face with conflict.

“My sensations as we approached what I supposed might be ‘a field of battle’ were anything but agreeable. I had been in all the engagements in Mexico that it was possible for one person to be in; but not in command. If someone else had been colonel and I had been lieutenant-colonel I do not think I would have felt any trepidation…”

After a night of sleep, Grant still did not feel better. He marched his men toward the enemy and “my heart kept getting higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.”

When he saw the valley below and saw that the Confederate “troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that [Confederate Missouri State Guard Brig. Gen. Thomas A.] Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him….From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he has as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.”

War is Hell

Grant’s admission that he found combat frightening is an important insight into his attitude. Too often, people believe that Civil War officers were fearless supermen, when in reality they were often frightened. And, as Grant indicated in his memoirs, it is also important to remember that command is not an easy task. Grant is often pictured as a butcher, an individual who threw his men into battle casually and needlessly. In fact, he felt, as they did, the fear of combat. War was not a romantic adventure; it was a place of terror, gore, and death.

Yet when he fought Robert E. Lee in Virginia in 1864-65, Grant fought him with all he had. He believed strongly that the only way to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia was to destroy it, to attack all Confederate forces on all fronts at the same time, and to wear away their fighting strength. Other Union generals had tried to outmaneuver Lee and his Confederate army and capture places rather than destroy their armies; they had failed.

Grant began his final campaign on May 3, 1864, in Virginia’s wilderness. He expressed his plans and the results he expected bluntly. “The campaign now begun was destined to result in heavier losses, to both armies, in a given time, than any previously suffered, but the carnage was to be limited to a single year and to accomplish all that had been anticipated or desired at the beginning of that time. We had to have hard fighting to achieve this. The armies had been confronting each other so long, without any decisive result, that they hardly knew which could whip.” As Grant realized, the next year saw desperate fighting, high casualties, but eventual victory for the Union troops.

Grant is often pictured as a butcher, an individual who threw his men into battle casually and needlessly. In fact, he felt, as they did, the fear of combat.

In April 1865, the war came to an end in Virginia with Grant’s all-out warfare wearing Lee’s forces down until the Confederates had insufficient manpower to fight back. After a bloody year, Grant broke through the lines at Petersburg and then pressed on to Richmond. He was clearly in command of the situation. What followed was a series of letters in which Grant called for Lee’s surrender, and Lee tried to delay so he could get the best terms possible. His first letter to Lee on April 7, 1865, was a classic. Grant wrote: “[T]he results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance….I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Grant’s Softer Side

Despite the hard war that he believed in, Grant made clear in his memoirs that he had a softer side, too. Instead of gloating about the beating he had inflicted on Lee and his army, Grant indicated that “my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

Grant also realized the appeal of Abraham Lincoln, the tragedy of his death, and the coming to power of Andrew Johnson. “Mr. Lincoln, I believe, wanted Mr. Davis to escape, because he did not wish to deal with the matter of his punishment….He thought blood enough had already been spilled to atone for our wickedness as a nation….He would have proven the best friend the South could have had, and saved much of the wrangling and bitterness of feeling brought out by reconstruction.”

Grant insisted that the “universally kind feeling expressed for me at a time when it was supposed that each day would prove my last, seemed to me the beginning of the answer to ‘Let us have peace.’” And, knowing that he was close to death, Grant completed his memoirs with the words, “I hope the good feeling inaugurated may continue to the end.”

Grant’s memoirs present a great insight into the general and his thinking. There is no better way of understanding this great American than by reading this outstanding self-evaluation, now published with the modern world in mind.

John F. Marszalek is W.L. Giles Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus, and Executive Director and Managing Editor of the Ulysses S. Grant Association’s U.S. Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State University in Starkville. He led the editing of the most recent edition of Grant’s memoirs, with assistance from editors David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.