Thunderous artillery fire echoed off the hills of the Rappahannock River valley. The early morning blasts delivered by 36 cannons that jarred the just-stirring Union army camps at Fredericksburg, Va., however, signaled not the beginning of a great battle. Instead the booming salute that summer 1862 morning opened Fourth of July celebrations for the U.S troops.

The Great Rebellion pulling at the Union was in its second year, and it was the 86th birthday of what a soldier in Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s “Black Hat” brigade of Midwestern regiments called “this great and once happy Republic.” William Ray of the 7th Wisconsin also added in his journal: “Oh, awful to think that a portion of its inhabitants have tried to & and Disgraced it to their utmost.”

Another of Gibbon’s men—James Northrup of the 2nd Wisconsin—also mentioned the holiday in a letter home: “I suppose you will have a good time….I hope so at least and hope you will not forget us Volunteers but enjoy a little fun for us.”

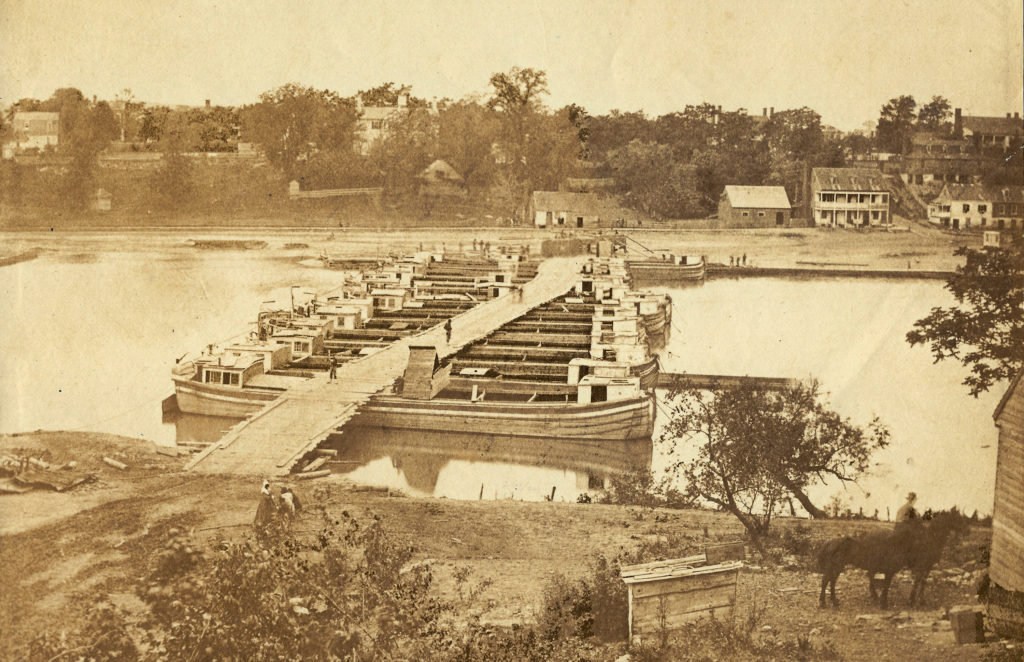

Of the current military situation, he wrote: “We are still laying on the north bank of the Rappahannock having an easy time of it. We have been expecting that we would be taken down to reinforced [Maj. Gen. George] McClellan but at present it looks as if we were elected to stay where we are for some time to come. The fact is somebody has got to stay here in case of a reverse to McClellan the rebels could march on to Washington without opposition.”

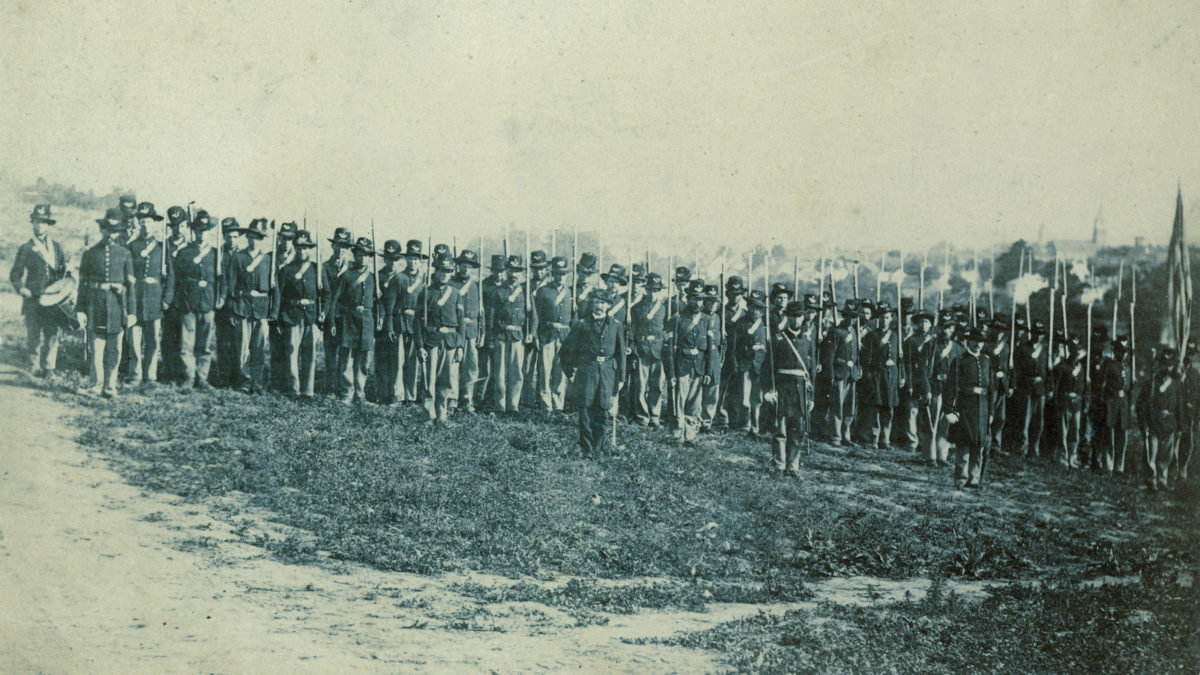

The two soldiers were part of a brigade that included the 2nd, 6th, 7th Wisconsin, and 19th Indiana along with Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery. It was the only infantry unit composed of regiments from the frontier West serving in the East, and was part of a force being held at Fredericksburg to protect central Virginia.

The western soldiers had marched into the Fredericksburg area in mid April, first passing through Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock as some of the 20,000 troops in Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Department of the Rappahannock. McDowell’s men had been sent to the colonial town, which a member of the 7th Wisconsin called the “greatest old foggy place I ever saw,” and placed in a position so they could either reinforce the Army of the Potomac’s Peninsula Campaign, or rush back to Washington, D.C., and protect the capital if necessary.

The brigade had been together since mid-summer of the previous year and—except for the 2nd Wisconsin, which fought at First Bull Run—saw only scattered and limited engagements with the enemy over the past months. “Of course, we feel eager to be something more than ornamental file-closers,” a frustrated Wisconsin officer wrote home. “Our regiment has been more than a year in service, and in soldierly bearing, perfection in drill, and discipline, we do not yield the palm to the regulars in any service.” Part of that “perfection” in drill was due to the advent of John Gibbon as the brigade’s new commander during its stay in Fredericksburg.

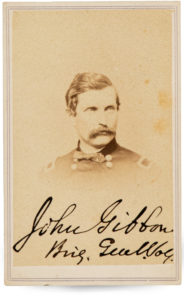

Gibbon had been promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in May 1862 from his Battery B, 4th U. S. Artillery. He was not greeted with enthusiasm. The new general was a Regular and West Pointer, after all, and the volunteer citizen soldiers were distrustful of Regulars. Adding to the dismay was the discovery the white gloves and linen leggings Gibbon added to the brigade uniform had to be paid out of the individual clothing allotments.

In ranks, Gibbon was regarded at first as an artillery officer who never commanded infantry. With brothers in the Confederate service, his loyalty was questioned, and his Old Army discipline and manner made him the most hated man in the brigade.

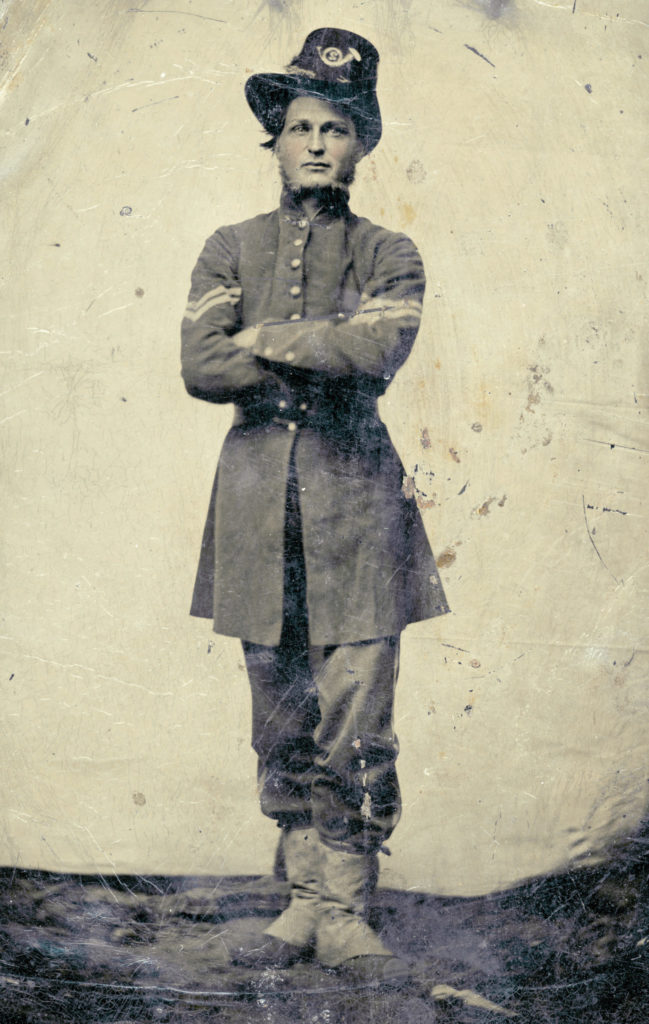

The Regular Army officer tightened up discipline and drill and also ordered new uniforms for his men. As did many of the early Federal regiments, the Wisconsin and Indiana units arrived at Washington in 1861 in uniforms of state militia gray. The changeover to Federal blue started in late summer 1861, in the Washington camps, first in the various companies of the ragged and needy 2nd Wisconsin where the boys were still wearing the uniforms of First Bull Run. The changeover was generally completed by May 1862 at Fredericksburg.

The new issue included dark or light blue wool trousers, a dark blue nine-button frock coat, and the Model 1858 black felt hat of the kind worn by the Regular Army. “The boys no longer look like beggars, with ventilated suits of clothing, but present a very neat, tidy and soldier-like appearance,” one Badger reported.

The new black hat made the biggest impression. It was a showy black felt affair, looped up on the side with a brass eagle and trimmed with an infantry-blue cord, black plume, brass infantry bugle, company letter and regimental numeral.

“The officers, a Badger wrote in his journal, “are coming right down on us as if we were so many slaves now and they are forcing leggings and blouse coats on us and forcing us to wear them. It’s a dime for this and a quarter for that and so it goes. And whatever the General says we must have, we must take it or be arrested…. I hate this putting on so much style. The boys call it putting on French airs.”

The four regiments brought 4,000 men to Washington the previous year, but even though fighting at Brawner’s Farm, South Mountain, Antietam, and Gettysburg lay in the future, transfers, other duties, desertions, and disease had reduced the brigade numbers. Now, an officer noted, only some 2,800 soldiers remained in the 40 companies.

But those men, mostly unused to battle’s trauma, were in high spirits even if they were suspect of General Gibbon and his ways, and planning for the brigade’s patriotic celebration had been underway for more than a month. The site selected for the event was “opposite Fredericksburg on a large section of the plantation formerly owned by the widow Washington, the mother of the first president and the father of the county,” said Jerome A. Watrous of the 6th Wisconsin. “The morning opened bright and warm and remained so all day.”

The holiday began on the company streets with the usual morning reveille and roll calls, but there were catcalls and shouts in ranks as the organizations formed. Privates in the 7th Wisconsin had elected new officers from men in the ranks and the “officers” immediately and eagerly took command of the regiment.

“There was, as a matter of course, considerable laughter in ranks but behaved well and obeyed orders which Our orderly said we must obey. And he couldn’t refrain from laughing himself at the novelty of the thing,” said Ray. “But as soon as we had got breakfast, the old cooks called on our Orderly to have somebody carry the breakfast to those that were on duty (as that is the way it is done). Orderly called at the top of his voice, J.B. Callis [7th Wisconsin Colonel John Callis] and informed that he had to carry the guards breakfast to him. This rather plagued him but go he must.”

While Lt. Col. Callis trudged off on his errand, other regimental officers were assigned to the cooking and water-carrying details. Non-commissioned officers made up the police details cleaning up the campgrounds under the watchful eyes of privates.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The guards came out dressed in their dirtiest and “most comical” uniforms, said Ray. “Our corporal had an old haversack for a hat, got an old knappsack which had been thrown away, and put it on with the canteen tied to the knappsack behind dangling about his legs and instead of a gun he had a verry large crooked stick, with paper stripes cut in a fantastic form on his arms.”

As the unusual detail formed, the large Newfoundland dog owned by Captain Alexander Gordon Jr. of Beloit, Wisc., was freed just as the guards passed. “This scattered the boys all over and the officer of guard with sword drawn tried to defend the guard and gets run over by three or four the guard which caused greater confusing in the ranks of the guard.”

At the Guard Mount, the new adjutant inspected the detail and found fault with some of the sticks used as guns “for not being clean (not having the bark and splinters off, two or three which he got in his hand)…. But after fussing about for about an hour and as fast the adjutant would get one in line another would run away.” Half of the officers were excused by the doctor and the rest were missing or hiding.

A “large plain” was used for the horse racing, foot racing, and other amusements and athletic exercises” including a “mule race, sack race and a greased pig,” said Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin. The “festivities and merry-making” went on most of the day with more artillery salutes at noon and again at sundown.

“The mules without number was run, then the horses, then foot races were run,” said Ray. “I guess every officer in the division was there and the whole of Gibbons Brigade and a few privates from other Brigades, but it was made for this Brigade only.”

The officers had gathered money for prizes. Wagon master William Sears of the 6th Wisconsin won the mule race on a track littered with soldiers who had toppled off their mounts, recalled Dawes. “The prize in this case was for the mule that got through last. Each rider accordingly whipped another’s mule, holding back his own.” Sears, he said, “rode a bulky mule which would go backward whenever whipped.”

A gray mare named “Bet” belonging to Adjutant John Russey of the 19th Indiana was the fastest in the horse racing and Colonel Sol Meredith of the same regiment, a farmer with a good eye for horseflesh, won $140 in the wagering.

A 6th Wisconsin soldier—John Ishmael of Cassville—got the first prize of $10 dollars as the fastest runner. Captain Hollon Richardson of the 7th Wisconsin immediately challenged him to a final race. The officer beat Ishmael but refused any money saying he just wanted to see if he “had lost speed any since coming to the army.” Other informal races continued until evening.

All was accepted as great fun by officers and men.

As the day ended, the massed drums of the four regiments called the soldiers together for a conclusion to the activities. The soldier selected for the final oration was a regimental favorite that one officer said “can talk on any subject and entertainingly”—Private Edwin C. Jones of the 6th Wisconsin.

“We are assembled on sacred soil, a portion of the plantation owned by the mother of George Washington,” Jones told the crowd of soldiers around him. “It was while living on this plantation, under the direction and blessed with the teaching of a noble mother, that George Washington learned those lessons…fitting him for leadership in war and peace, to lay the foundation of the mighty Nation that we today are fighting to preserve.”

Jones went on: “Over yonder back of the City of Fredericksburg, in a little cemetery, sleeps that noble mother who gave to the Nation its richest and rarest gift. I suggest that we 3,000 Western soldiers turn our faces in the direction of Mary Washington grave and bow our heads in honor and to the memory of the mother of the father of this great country of ours.”

Watrous remembered that “every one of the 3,000 browned faces” looked in the direction of Mary Washington’s grave across the river and every head was reverently bowed.

“On yonder hills there is an armed force pledged to destroy the government founded by George Washington,” Jones paused, then said in a loud voice. “But by the living God they shall not do it.”

Up to that time the audience had listened spell-bound, said Watrous, “but in an instant hats flew in the air, cheers were given for the orator, for the American flag, for the American Nation, and such cheers as are not often heard.”

Back in camp, the new “officers” of the 7th Wisconsin issued a series of humorous orders, and finally, in a more sincere tone, thanked the regular commanders for their forbearance, singling out Colonel William Robinson “for the levity he has allowed us &c and expressing the greatest confidence in him as a man to lead us to the battle.”

In his journal, Ray admitted the brigade had made “quite a demonstration” and it was not something that could have been done at home. “But when we do get home,” he concluded, “we will try to raise a Co for the next fourth after.”

Another soldier wrote in a letter home of the “best part of the day” was the $2.00 worth of fire works” purchased by Maj. Gen. Rufus King, their former brigade commander who had ascended to division command.

That such an unusual event could occur in an American military organization was explained by a 2nd Wisconsin man. The Western boys, he observed, were “more lively by far than the other troops that are with us. We have more music, more dancing, more athletic sports and more real fun and good humor than the Eastern boys, and it is generally admitted that we are not bad on a march.”

Around their coffee fires, however, the Western boys privately wondered and worried aloud about something more important—how could they ever explain their lack of real service to the folks back home. The war itself seemed to have no hope of a quick conclusion. The North was still reeling from the long causality lists from the fighting in April at Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee. The Confederates were still in the field across the nation’s whole front, and it seemed the leadership of the North just did not know what to do about it.

If the men from Wisconsin and Indiana fretted the long weeks of summer under a heavy schedule of drills, reviews, work details, and camp policing as well as several forays into the countryside in search of Confederates, the volunteers were also plagued by a lingering and troubling doubt—how would they behave in actual battle.

They were untested as a brigade and if the units were singled out for their frontier origins and new black hats, the four had “their individuality, their rivalry, their jealousies, if you will,” one observer said. “The 2d had been through First Bull and swaggered a bit in consequence. They rather patronized the other regiments, put on veteran airs. They were superbly drilled, but decidedly given to sarcastic comment on the other commands. The 6th, 7th and 19th had not had the 2d’s opportunities, but were cock sure that when the time came they could fight every bit as well, stay as long in a hot place or charge just as daringly into a hotter.”

Indiana and Wisconsin seemed far away to the volunteer citizen soldiers, with home a faded memory caught in a clutch of treasured letters and pictures. If they were first known just as a Western brigade—the only such infantry organization in the East—the new hats were now making them “Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade,” and in just a few weeks they would become the “Iron Brigade of the West.”

But that was yet to come. The innocent Westerners had been marched here and there for more than a year, and now, just a few weeks ahead, on Aug. 28, 1862, they would find their “elephant” on a farm leased by John Brawner, not far from where First Bull Run was fought in July 1861.

It would be a date long remembered in many Wisconsin and Indiana homes.

Lance J. Herdegen has authored several Civil War books, and his latest is a Savas Beatie reprint of the award-winning In the Bloody Railroad at Gettysburg: The Sixth Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade and its Famous Charge.

The Iron Brigade Speaks: Check out author Lance Herdegen’s list of his favorite published Iron Brigade diaries and letters.