‘Quite possibly it was Villa’s idea, as he loved movies and enjoyed watching himself in early newsreels’

On Jan. 26, 1914, a ragtag revolutionary army of some 10,000 infantry and cavalry, led by a wily and charismatic horseman named José Doroteo Arango Arámbula—better known as Francisco “Pancho” Villa—approached the city of Durango, capital of the Mexican state of the same name. Villa was then commander of the División del Norte and caudillo, or leader, of the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. His imminent attack on Durango was part of a larger campaign to march on Mexico City and wrest control of a bloody revolution that since 1910 had sundered the nation. Refugees from the fighting told Villa of a strong federal garrison inside Durango. Villa—something of a natural tactician and by then a veteran skirmisher—sent his cavalry armed with modern rifles to encircle the garrison and cut off any retreat. Although Villa’s horse soldiers wore motley, makeshift uniforms, they reportedly maneuvered with all the élan of U.S. Army regulars.

As the cavalry split up and rode off on their flanking movement, the rebel infantry prepared for a frontal assault on the garrison. They formed into three long battle lines and attacked with a fervor conspicuously absent among the more smartly dressed federales.

Once Villa’s men swarmed over the walls and battered their way through the front gate, the battle for Durango ended quickly—too quickly for a pair of noncombatants closely following the action: Raoul Walsh, a handsome young American actor and (soon to be famous) director, and Hennie Aussenberg, his veteran German cameraman. Their presence signaled one of the strangest episodes in American cine-ma and a first in military history. For American film pioneer D.W. Griffith’s Mutual Film Corp. they were shooting a feature movie—docudrama? newsreel? reality show?—about Villa, even as the general’s troops fought an actual bloody revolutionary war, with real casualties.

Walsh and Aussenberg advanced into Durango with Villa’s infantry, occasionally stepping over the body of a fallen Villista. Bullets had splattered around them, and they had gotten some dramatic footage of the fighting, but to their disappointment most of the combat was over by the time they entered town. The rebels were rounding up prisoners and hanging several federales accused of murdering civilians, and Villa had already entered Durango.

Walsh decided he needed to restage history. He asked one of Villa’s officers to coax the general into riding through the city gates again, this time with his victorious troops whooping, shouting and firing their weapons into the air. Villa loved the idea. The general was, as Walsh later observed, “a hog for publicity.” Villa had his military victory. Walsh would soon have his movie.

From 1912 into the 1960s Raoul Walsh acted in, directed or produced nearly 150 films. Starting as a protégé of D.W. Griffith—he played John Wilkes Booth in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915)—Walsh did more to establish the careers of great film actors than any other filmmaker: John Wayne, whose breakthrough film was Walsh’s The Big Trail (1930); James Cagney, whom he directed in two gangster classics, The Roaring Twenties (1939) and White Heat (1949); Errol Flynn, as George Armstrong Custer in They Died With Their Boots On (1941); and Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino, who became major stars in the film noir classic High Sierra (1941). Yet the most improbable feature Walsh directed was his first, starring the real-life revolutionary Villa.

The revolution itself had begun in 1910 as a revolt against longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz and devolved into a bloody civil war, with numerous factions fighting for control of Mexico. Francisco Madero, an aristocratic idealist and progressive, had become president after Díaz was deposed. In 1913 Madero was forced to resign, then betrayed and assassinated by one of his generals, Victoriano Huerta, who soon assumed power. In 1914 Huerta, too, was overthrown after little more than a year of unrest capped by the American occupation of Veracruz. Venustiano Carranza, once a minister of war in Madero’s cabinet, became president. Carranza, an educated man from a prosperous family, lacked the sympathy for land reform that motivated revolutionaries like Villa. He attempted to call at least a temporary halt to the revolution. Villa, who believed the revolution’s major aims had not been achieved, began fighting on his own.

The mountainous state of Chihuahua was a natural base from which to carry on a revolution. It bordered the United States, which could be either an advantage or a detriment, depending on how one played politics. To Villa, even then a media-savvy revolutionary, it proved an advantageous location. He was mindful of the importance of newspaper coverage of his exploits and was intrigued by the possibilities of what was then a nascent medium: motion pictures. No one knows how Villa and Griffith first made contact. Quite possibly it was Villa’s idea, as he loved movies and enjoyed watching himself in the early newsreels. What is known is that on Jan. 5, 1914, only a few weeks after his soldados occupied Ciudad Chihuahua in an attempt to cripple government power in the north, Villa signed a contract with Griffith’s Mutual Film, represented by partner Harry E. Aitken.

Two days later The New York Times reported on the deal:

The business of General Villa will be to provide moving picture thrillers in any way that is consistent with his plans to depose and drive General Huerta out of Mexico, and the business of Mr. Aitken, the other partner, will be to distribute the resulting films throughout the peaceable sections of Mexico and the United States and Canada. To make sure that the business will be a success, Mr. Aitken dispatched to General Villa’s camp last Saturday a squad of four moving picture men with apparatus designed especially to take pictures on battlefields.

“For the film industry,” Friedrich Katz wrote in his The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, “this contract was very important. Newsreels were a relatively new genre, and the film industry was greatly interested in their development. For the first time, people who had never been involved in a war could actually see what war was like.”

Walsh would recall some 60 years later in his highly embellished 1974 memoir, Every Man in His Time, that he was watching dailies in a California projection room when he got the call from producer Frank Woods, who said Griffith wanted to see him right away.

“Mr. Woods tells me you have spent some time in Mexico,” Griffith said. Walsh confirmed he had. Griffith introduced him to two of Mutual’s moneymen from New York and explained what seemed an outlandish idea: Mutual had made a deal with Villa to shoot a picture about him and his army, which was then in Chihuahua preparing for a new campaign. Did Walsh want the job? Without hesitation he said he did. “You will direct the picture,” Griffith said. “Mutual will supply a cameraman, and General Villa will be paid $500 in gold each month while the production is going on.”

Griffith did not mention then that Walsh would have a double assignment: The picture would be a blend of fiction and documentary, and in the fictional part Walsh himself would be playing Villa as a young man. All Walsh wanted to know was when would he start. He would be leaving in about four hours, Griffith told him. There was no script; Griffith gave him a fanciful biography of Villa that supposedly would fill him on the general’s early life. (Walsh later said he had only three hours to read the book during the 800-plus-mile train ride from Los Angeles to El Paso.) Griffith’s parting words were, “That should give you time to start the story. The sequences will take care of themselves. Good luck, Mr. Walsh.” And so Albert Edward “Raoul” Walsh, 27, actor and aspiring filmmaker, former sailor and cowboy, headed for revolutionary Mexico and the strangest adventure of his life.

As Walsh boarded the Sunset Limited at Los Angeles’ Union Station, he got one more piece of advice from Woods: “Think up a story that the general will like, and for God’s sake, never refer to him as a bandit.”

When Walsh arrived in El Paso, he met Villa lieutenant Manuel Ortega, “a middle-aged Mexican in the biggest sombrero I had ever yet seen.” Walsh had the foresight to dress Western style, in hand-stitched boots and leather jacket, topped by a carefully rolled Stetson. The two climbed into a waiting car and sped off across the border. As they approached Villa’s headquarters somewhere near Chihuahua’s capital city, Ortega had one request: that the American wear a blindfold. Why? Walsh wondered, given that every child in Juárez certainly knew of Villa’s whereabouts. Whatever the reason, Walsh decided, it added more drama to the situation.

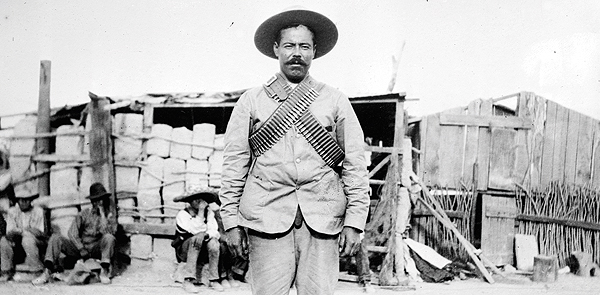

Villa’s camp, Walsh observed, was nothing like any army installation he had ever seen: “There were no tents. Everybody was stretched out on blankets and serapes, and none of the soldiers wore uniforms: a big sombrero, dirty cotton trousers and shirt, a bandolier of bullets and a gun were all that distinguished them from the hucksters and enchilada peddlers.” He met and shook hands with the general. Walsh found him “a big man physically: big black mustache, big head, wide shoulders, thick body and eyes that reminded me of something wild in a cage.” He was, Walsh thought on meeting him, naturally charismatic. Ortega announced, “The general wants to see the money.” Walsh opened his satchel and put it on the table; Villa took a $20 gold piece, turned it over in his fingers and dropped it back in the bag.

On the journey from Los Angeles, Walsh had had an intuitive flash: Present the script idea orally, not in written form. So he’d memorized his notes. “The picture,” he told Villa and his staff, “will be seen by millions of people in the United States and other countries. It will show General Villa as a boy, living with his mother and sister outside Hidalgo del Parral. As he grew up, he got work as a vaquero on a nearby ranch.…When he heard of an opening on the big Terrazas hacienda in southern Chihuahua, he embraced his mother and sister and rode away after leaving them the little money he had.”

Translate that to the general, Walsh told Ortega, and see if he likes it. Actually, while Villa felt awkward about speaking English, he understood it fairly well and already liked the Hollywood flair of the story. The rest of Walsh’s plot involved Villa returning to Parral to find his mother and sister raped and murdered by federales—at least that’s the way Walsh related it in his autobiography. Actually, Villa did maintain that one of the owners of the hacienda where he was born tried to rape his sister, and Villa shot him in revenge; Frank McLynn, author of Villa and Zapata, casts doubt on the veracity of this incident, but Villa certainly appreciated the impact of the story. Walsh noted that as Villa listened, his eyes changed: “Now they shone as he licked his lips briefly. I thought of a jaguar getting ready to spring.”

Walsh ran through some of the lines Villa’s character would relate in captions on the silent screen: “I swear before God that I will raise an army and destroy these murderers. Then I will ride to Mexico City and pull down the government which hires them.” The general smiled and nodded. “He wishes to congratulate you,” Ortega said. “The general says he will be pleased for you to make the story, and he will take good care of you, because if you were killed, there will be no picture for the world to see.”

Walsh’s cameraman finally arrived, and the campaign—both Villa’s and Walsh’s—began. Villa’s men had commandeered a train belonging to the Mexican Central Railroad and piled the boxcars high with military equipment and cans of water. The water, Walsh noted, was yellow and muddied; “I would not have washed a dog in it, let alone drink the stuff.” He instructed an assistant to ride back to El Paso and fill some cans with potable water.

The revolutionary army’s first destination was the federal-held town of Durango, south of Parral, which they took in a matter of hours. Villa’s final destination was Mexico City and control of the nation. But while still in Durango, Walsh and Villa continued to tailor revolutionary realities to fit their film: When the Villistas released a few woebegone prisoners from the Durango jail, Walsh restaged the event in a more cinematic style. He conferred with Ortega and Villa, and the general ordered several companies of his men to doff their sombreros and bandoliers, stack their rifles and enter the jail. The soldiers, initially confused, were then instructed that when one of Villa’s lieutenants fired his pistol, they were to rush from the jail yelling, “Viva, Villa!” in praise of their “liberator.” One soldier—perhaps an early proponent of method acting—got so enthusiastic that he ran up, grabbed his commanding officer by the ankle and kissed his boot.

Walsh even staged a mock battle between Villa’s soldiers and some “federales.” On Villa’s orders his reluctant soldados stripped caps, boots and bloody jackets off their dead enemies. “Once they got over their reluctance to don the hated uniforms,” Walsh later wrote, “everything became a big joke to them. I had never heard of troops under fire grinning like apes at one another or the enemy.”

While filming the combat scenes, Walsh decided Villa’s men didn’t look “martial” enough—neither, for that matter, did the general. Someone on the crew hastily assembled a formal uniform for Villa, who wore it proudly for the movie and then promptly discarded it. That episode led to one of the strangest rumors of the campaign. According to a later account by Walsh, during production Villa’s troops wore what appeared to be regular army uniforms, which the director claimed Griffith had donated. The uniforms reportedly looked very much like those worn by Griffith’s Confederate soldiers in Birth of a Nation. Thus Villa may have appeared in his autobiographical film wearing the uniform of a Confederate Civil War officer. The problem with the story is that Birth of a Nation wasn’t filmed until after Walsh returned from Mexico; it is possible, though, that Griffith had contributed surplus uniforms ordered in advance for his Civil War epic. The story has never been verified.

When the revolutionary army left Durango for the nearly 500-mile journey to Mexico City, it had grown to nearly 9,000 men, many armed with rifles, pistols (including U.S. Army Colt automatics) and even some machine guns purchased with the gold from Griffith’s Mutual Films. Villa’s army marched into Mexico City on February 17. The occupation of the capital city, compared to the Durango campaign, was relatively bloodless. By then, the federales had begun to lose heart. When they saw the giant dust cloud kicked up by Villa’s approaching army, they fled the city. Villa, hailed as a benevolent conqueror, rode into the capital to shouts of adulation.

Walsh finished his interior filming by throwing open doors and windows in Chapultepec Castle and within three days had sufficient footage to pack up for the long trip back to Hollywood. The journey was far from easy; Mexico had few decent roads, and travel by truck was hazardous. It took Walsh’s three trucks, loaded with food and barrels of gasoline, three weeks to make the dusty, bumpy ride to Juárez. From there he caught a train to Los Angeles where, almost immediately, he began filming the studio sequences at Mission San Fernando, standing in for Villa as the young Pancho. He finished the scenes in less than a week, and after some frenzied editing, the eager studio had its feature-length five reels. Griffith and Woods were enthusiastic about Walsh’s work: “Some of the shots are good and bloody,” Walsh recalled Griffith saying. “The censors may faint,” he added, referring to the shots of federales hanging from trees in Durango, “but that’s Mutual’s headache.”

The Life of General Villa premiered in New York on May 14, 1914, to generally favorable reviews. It was released on different dates and under different titles (The Life of General Villa, The Tragedy and the Career of General Villa, The Tragic Early Life of General Villa) in other parts of the country. The film seemed to do well at the box office, but producers never told Walsh how much it grossed. According to Katz, “The film was shown in several U.S. cities and seems to have been a great success, partly because it was shown at a time when Villa had reached the apex of his popularity.”

The goodwill was not to last. Toward the end of 1914 Villa finally broke with Carranza, who persuaded the Wilson administration to cut off all aid to Villa’s army. This sparked Villa’s infamous March 1916 raid on Columbus, N.M., in which his men killed several American citizens. Wilson then ordered General John J. Pershing on a fruitless attempt to chase down the rebel general. Almost overnight, Hollywood’s perception of Villa reversed. Pershing never caught Villa. The Mexican Revolution came to an uneasy truce between Carranza and Villa. In 1920, with the assassination of Carranza, the new president, General Álvaro Obregón, gave Villa a hacienda near his old home in Parral. On July 20, 1923, while visiting town without his usual bodyguards, Villa himself was ambushed and assassinated, reportedly with Obregón’s approval.

Walsh’s innovative war movie has been lost to history for almost 90 years, as has the role of an American movie company in financing a revolution south of the border. And for the rest of his life, Walsh would wonder, Had I directed Villa, or had he directed me?

For further reading Allen Barra recommends The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, by Friedrich Katz.