The history of Pan American World Airways’ involvement in the Vietnam War began decades before the last Boeing Jumbo 747 departed Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport on April 24, 1975, as the city was about to fall to communist forces. It began in the 1930s during the events leading to World War II.

After several meetings with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Juan Trippe, Pan Am’s president, allowed the company’s aircraft and operations to become America’s outreach to the world, “showing the flag” to establish a global presence that countered Axis aggressions. During World War II, New York-based Pan Am and other airlines provided major support to the war effort, especially at the outset when the government’s capability was limited. Besides operating regular passenger service, Pan Am turned its fleet of giant Clipper flying boats over to the government for high-value military and civilian passengers. Transports carried critical military equipment and supplied outposts. The airline touted itself as the government’s “chosen instrument” and “the second line of defense.”

With the end of World War II, the government began selling surplus aircraft believing planes in such vast numbers were no longer needed. Scrapyards were filled with discarded military equipment. Suddenly, on June 24, 1948, the need for aircraft changed dramatically when the Soviets imposed a blockade of the road, rail and canal routes into the Western Allies’ sectors of Berlin. The only option was to supply the inhabitants with life-sustaining food and coal by air. From June 24 until the blockade was lifted on Sept. 30, 1949, Allied planes—including those of Pan Am and other commercial carriers—flew 278,228 flights into blockaded Berlin, losing 25 aircraft and 101 lives from accidents during the Berlin Airlift.

When the Korean War erupted nine months after the end of the Berlin Blockade, President Harry S. Truman’s administration recognized that a formal pact had to be secured to employ civilian aircraft in times of crisis. On Dec. 15, 1951, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Lovett and Commerce Secretary Charles Sawyer signed a joint agreement establishing the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, a voluntary program in which participating civilian airlines committed their planes to the military in a national emergency. Pan Am signed on. Over the years Trippe had disagreements with the federal government over routes or regulations, but he was first and foremost a patriot—when the president called and made a request, he did it!

By 1952 Trippe’s airline had transported 343,000 Korean War troops and 48,000 wounded under routine, non-emergency military contracts.

As the military buildup in Vietnam increased in 1965, Pan Am was operating 40 flights each week between California and Saigon. The flights going to Saigon included in-bound troops, along with military and medical supplies, ammunition and oil. Around the Christmas holidays, entertainment troupes and Christmas trees arrived on Pan Am planes.

By the end of the war Pan Am had transported more medical supplies, cargo and troops than any other civilian airline. In the beginning, most of the aircraft were piston-driven Douglas DC-6s. By early 1969, some 12 percent of Pan Am’s jet aircraft were involved in the war in Southeast Asia. After three years the DC-6s were replaced by Boeing 707s and 727s. By 1969 Pan Am operated 104 aircraft of various types in the war zone, the most of any civilian airline.

As 1966 dawned it became apparent to military officials that the troops fighting in Vietnam needed periods of relief. However, the time and cost of flying men to the United States for a week’s rest and recuperation would be too great and unfeasible, especially since planes were needed for the 50,000 service members sent to Vietnam each month to meet the war’s growing demands.

On Feb. 2, 1966, Pan Am’s president, Harold Gray—a Pan Am Clipper pilot in the 1930s and ’40s—signed an agreement with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration to provide R&R flights for troops in Vietnam. The charge to the U.S. government would be cost plus $1. This R&R operation began almost immediately. On Feb. 25, two DC-6Bs were transferred from their German routes to full-time operation in Vietnam. The operation was organized by Thomas Flanagan, one of Pan Am’s most experienced pilots. It involved 35 six-member crews and 100 maintenance personnel—all volunteers.

On March 1, the first flight took off. In the first month of operation 1,800 service members made R&R trips. The initial flights went to Hong Kong, then later to Tokyo. By the end of 1966, Pan Am had added trips to Guam, Taipei, Sydney, Bangkok and Hawaii, a popular destination, and taken more than 100,00 troops on R&R flights.

As the numbers of men and women increased during the war, so did the R&R runs, eventually reaching 18 flights per day. DC-6s were replaced with 707 jets. The aircraft departed from Cam Ranh Bay, Nha Trang and Da Nang.

All service members on Pan Am R&R flights were treated like first-class passengers. Many were just 18 or 19 years old and had never been away from home before their induction into the military nor flown as civilians—making the flight itself a treat. The meal consisted of Kobe steak, home fries or French fries, green beans, milk and ice cream for dessert. In one month, 9 tons of steak, 9,000 quarts of milk and 5 tons of ice cream were served. Flight crews, once on the ground, generally sought out restaurants that did not serve steak. One steak was nice, but not so many times in a week.

One aspect of the R&R flights has received little attention over the past 50 years: the role of Pan Am stewardesses. Like many of the troops, the stewardesses never had a parade. Even worse, they received no medals or even certificates for their service, although the flight crews did. The stewardesses were mostly new Pan Am recruits about the same age as the young men they were serving. Those who worked on the Vietnam flights were volunteers and given the rank of second lieutenant in the Air Force while in the war zone. If captured, they would be covered by the protections of the Geneva Convention, an international agreement after World War II that established the rights of military prisoners of war.

Pan Am was the last of the major airlines to employ women for its passenger services. Until the last year of World War II Pan Am cabin crews were all male. A shortage of available men because of the military’s war demands finally convinced Pan Am to hire women for its cabin crews. The process to become a stewardess was difficult. Only one of every 100 who applied was accepted. The stewardesses were required to wear a girdle and stockings. Their hair could only reach the cheekbone. They could not be married, nor more than 5 feet, 5 inches tall and 125 pounds. Makeup was limited to four specific colors approved by the airline. Pan Am did not hire its first African American stewardess until 1970.

Like military veterans’ organizations, Pan Am’s stewardesses have their own reunions. Members of Wings Over the World meet and talk about their experiences in the Vietnam War. They reminiscence about things they did to make the flight more enjoyable and relaxing for the troops, such as baking cookies at home and warming them on the plane so the smell would fill the passenger cabin. Pan Am provided special paper for men to write letters home, and many stewardesses became pen pals. Some still hear from men who were on R&R flights. Richard Upchurch, an Air Force sergeant who was on an R&R flight in mid-1968, wrote in a publication of the Pan Am Historical Foundation, “I always wanted to thank Pan Am and all the Crews and Flight Attendants for a wonderful slice of the States, for a short time anyhow.”

Almost all of the stewardesses remember their first landing in Vietnam, when they looked out the windows and saw bomb craters, burning wreckage and planes and helicopters coming and going. Every flight had a quick turnaround time, so crews had to immediately clean the aircraft, do maintenance work and get one group of men off and another on.

“If you go into Vietnam as a stewardess with any sort of feeling for or against the war, you’re dead,” said stewardess Nancy Hughes, in a wartime interview with The Main Line Times in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, her hometown. “What you see is 170 human beings on the airplane and you have to accept it as that. You can’t like or dislike it…In the job I have, it’s always the men I remember best. I’ll always remember these men.”

Pan Am advertised itself as the “World’s Most Experienced Airline,” with 86 destinations, 150 jets and 67 million passengers. Its “Blue Ball” logo was recognized across the globe. Pan Am didn’t achieve that status without self-promotion, and its role in the Vietnam War figured prominently in that campaign. Annual reports usually had photos of men, stewardesses or aircraft intermingled with military C-130 Hercules transport planes or other aircraft in Saigon or Da Nang. The annual report of 1966, the first year of the R&R program, featured a painting of a young Marine standing next to a sign that stated: “Pan Am flight CKAP 246 Saigon to Honolulu.” In the distance, other Marines were getting ready to board the Clipper Friendship.

As the war neared its end, Pan Am was involved in two other major undertakings. The first was the Operation Babylift evacuation of orphans, instituted by President Gerald Ford, who had been lobbied by many organizations, including the Pearl S. Buck Foundation (focused on impoverished children in Asia), Friends of Children of Viet Nam and Holt International Children’s Services. On April 3, 1975, Ford announced that $2 million would be authorized to arrange flights on C-5A Galaxy and C-141 Starlifter military transports and Pan Am planes.

Operation Babylift was under the command of Air Force Maj. Gen. Edward J. Nash. The first flight, on April 4 with a C-5A, ended in tragedy when the cargo door flew off and the aircraft crashed in a rice paddy. The disaster killed 138 people, including 78 children, in the aircraft’s lower cargo section.

Other aircraft continued the flights. A chartered Pan Am Boeing 747 reached San Francisco on April 5 with 325 infants and children, including the survivors of the C-5A crash. There were 60 escorts on the aircraft. The men on the flight claimed they had learned how to diaper a baby shortly before boarding the plane. There were too many infants and children to strap all of them into seats. Some infants were placed in blue Pan American cardboard bassinets and stashed under seats. Hundreds of baby bottles had to be prepared, since the entire flight might be as long as 30 hours depending on where the aircraft landed.

Stewardesses recall the deafening sounds of hundreds of babies crying at the same time, waiting to be fed and needing diapers changed. There were other volunteers on the aircraft to assist them, but it was still a difficult flight.

Ford and first lady Betty Ford were at the airport to greet them. The president carried the first child off the aircraft. The Pan Am flight was chartered and funded by Robert Macauley, the owner of a paper company, who used $250,000 of his own money.

“Somebody has to do it,” he told The New York Times. “It was only money, against saving the lives of 300 to 400 children.” Another Pan Am flight had arrived in San Francisco earlier. A third went to Seattle, carrying 407 children around midnight.

Twenty buses took the children from the flight Ford met to the military facility at San Francisco’s Presidio, where they were registered into the country and met by 26 Red Cross volunteers. Also waiting for them were 7,886 bottles of baby formula, 10,000 disposable diapers and 2,400 cotton swabs. Makeshift beds with blankets for the infants had been arranged on the floor.

The children wore bracelets with their Vietnamese names on one hand. On the other was information about the family adopting them. My niece was on the flight that Ford met. She was flown from San Francisco to Boulder, Colorado, and greeted by Friends for All Children, an adoption service participating in the evacuation. Shortly thereafter she was on an aircraft that took her to Los Angeles and the home of her adoptive parents, my wife’s brother and his spouse.

Friends for All Children also sponsored orphans who arrived on the “Giant Bunny” aircraft of Playboy magazine publisher Hugh Hefner. When the plane landed in San Francisco, it was met by Playboy bunnies. The Giant Bunny flew 41 orphans to various destinations in the United States. Pan Am charters also delivered babies to London, Australia, Germany and Canada. The last flight out included 59 taken to Ontario. The total number of children evacuated is uncertain due to the chaos in the last days before Saigon fell but is estimated at 2,500 to 3,300. The newly unified Vietnam maintained that infants and children had been taken out of the country illegally. In the end nothing came of Hanoi’s demands.

During those turbulent final days of the Vietnam War, Pan Am would undertake secret flights or missions if needed. Yet the company took care of its employees and got them out of harm’s way, as it had done in World War II.

As the North Vietnamese Army rapidly approached Saigon in April 1975, the Federal Aviation Administration on April 24 banned all commercial flights. Trippe sought special permission for a final flight on that date, using a Boeing 747 jumbo jet named “Unity,” to get all of his remaining employees flown out. That included the Vietnamese ground staff and their families. Ford personally approved the mission. Once all the maintenance staff was pulled out, no more Pan Am service would be available.

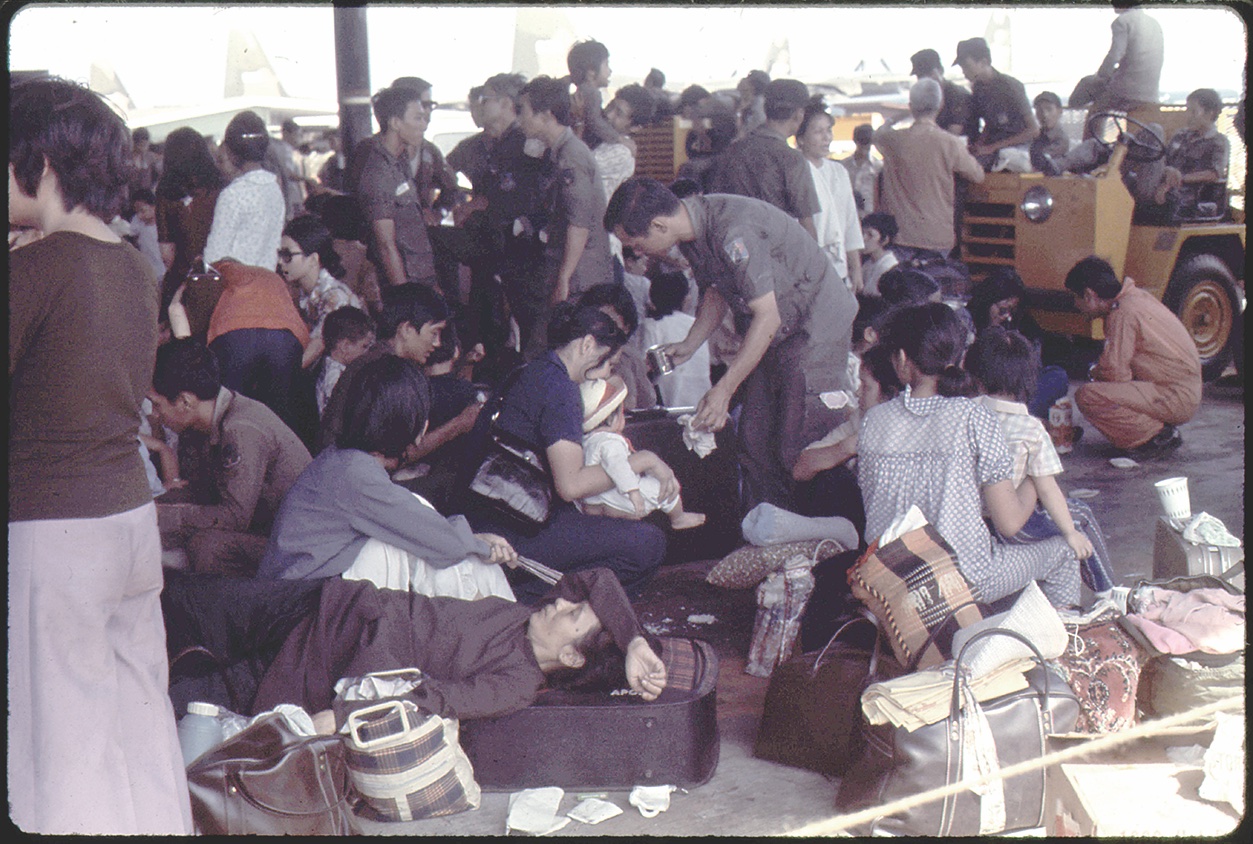

Before the precise date was set, Pan Am, knowing the end was near, had asked for volunteers to make the last flight and sent them to Guam to wait for the airline’s senior executives to determine when the final flight would be made. That aircraft would not take any luggage or personal belongings of the passengers. Life vests, rafts and other standard items were offloaded to make the plane lighter. Safety regulations would not be enforced. Passengers would be allowed to sit on the cabin floor. The goal was to get as many people out as possible.

Pan Am’s station manager in Saigon, Al Topping, had already begun making preparations. “The days leading up to our final departure contained many situations of uncertainty and drama,” Topping wrote in an account on the Pan Am Historical Foundation’s website. “I knew what we had to do. I was just not so sure how we would accomplish the mission.”

Many of Pan Am’s Vietnamese employees did not have the proper documents to leave the country. Processing their exit papers would normally take two to three months. Topping had an idea. He would try the same tactic that worked with Operation Babylift: adoption. He asked the South Vietnamese government to allow Pan Am to adopt its employees. “It worked,” Topping wrote. The airline got adoption papers for 315 South Vietnamese—Pan Am employees and their immediate families.

On April 23, Topping told all employees and their families to be ready the next morning at the ticket office for buses to take them to the airport. That night, many slept in the downtown office to make sure they would be able to meet the buses.

One of Pan Am’s most experienced pilots, Bob Berg, flew the Boeing 747 into Tan Son Nhut airport. Once Berg landed, he told crew members disembarking so they could assist the evacuees that when it was time to board he would flash the plane’s red lights. He promised that no one would be left behind.

As employees and their families boarded the aircraft, masses of people swarmed the other side of the runway fence, hoping they could find a way onto the plane. Crew members tried to get as many on as possible. To slip by airport guards, some women disguised themselves as stewardesses by wearing Pan Am uniforms and wigs that the crew had brought for that purpose. Many others found that bribes were the tickets that got them past the guards.

Eventually it was not safe to take on any more passengers. “With captain Bob Berg in command and an all-volunteer crew we headed for Clark AFB in the Philippines with 463 souls on board,” Topping wrote.

The plane’s official capacity was 375. From Clark Air Force Base it was on to Guam, where the refugees would be resettled. A headline the next day in the Los Angeles Times proclaimed: “315 ‘Adopted’ By Airline: Refugees Reach Guam on Cloak-Dagger Flight.”

An NBC television movie starring Richard Crenna and James Earl Jones, Last Flight Out, was broadcast in 1990, and a documentary film, Operation Babylift: The Lost Children of Vietnam, was released in 2009.

Pan American World Airways has since disappeared. In its time, it was part of major historical events that engulfed the United States during the Vietnam War, when it truly lived up to its nickname “America’s Airline.” V

Jim Trautman, a former Marine, wrote The Pan American Clippers—The Golden Age of Flying Boats, a book first published in 2007 and updated in 2019. He lives in Kitchener, Ontario.

This article appeared in the February 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.