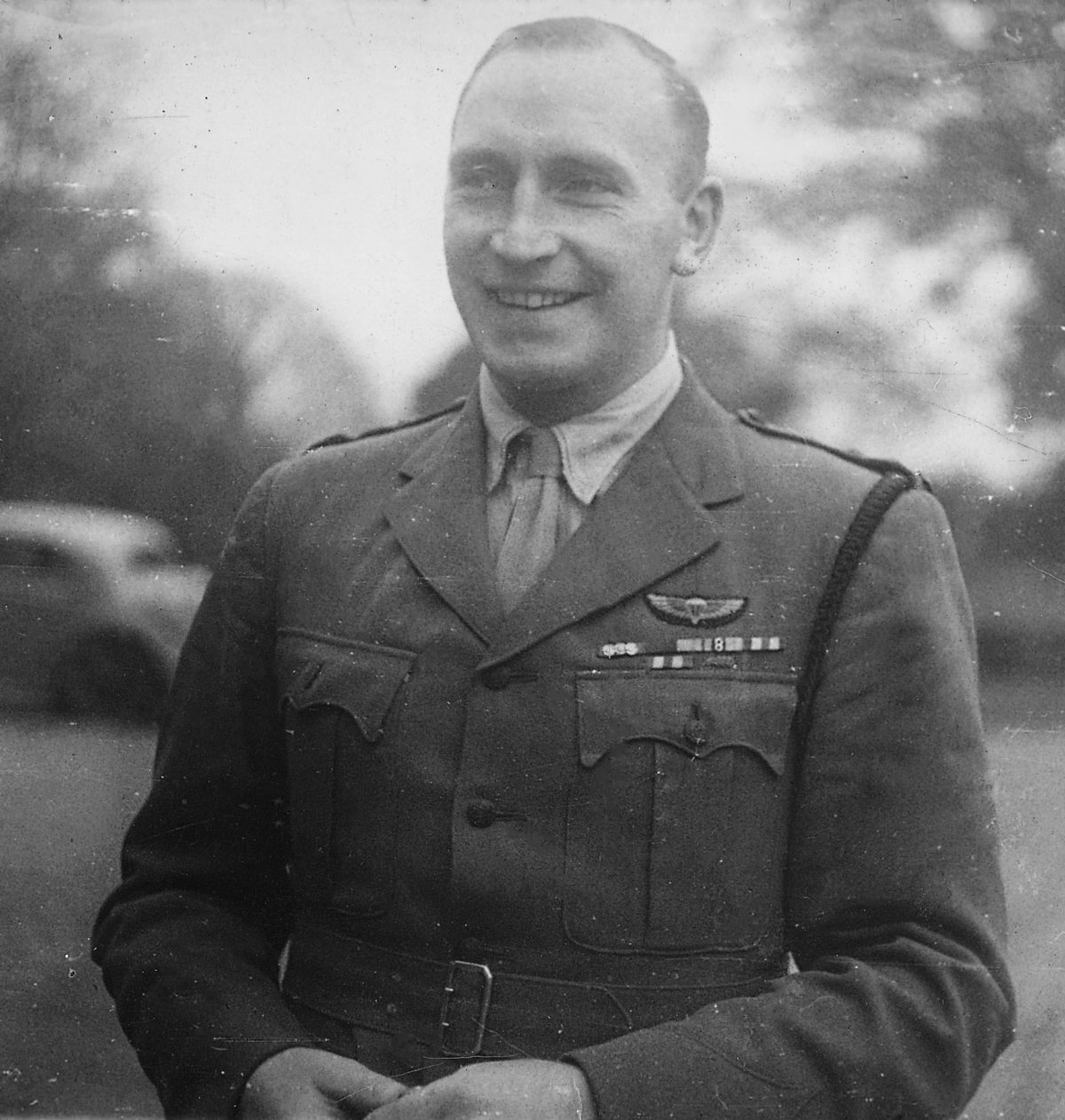

On the night before Christmas 1941, a tall athletic man crept unseen onto an Italian airstrip at Tamet, on the Libyan coast, midway between Tripoli to the west and Benghazi in the east. Lt. Robert Blair Mayne, “Paddy” to his acquaintances, was accompanied by five other raiders of Britain’s deadly Special Air Service.

A fortnight earlier Mayne and a similar-sized raiding party had visited Tamet for the first time, destroying 24 aircraft and bursting into an Italian billet, shooting dead about 30 startled aircrew. The Italians had since tightened security, but the 6ft 2in Mayne led his men onto the airfield without impediment.

“The enemy was on the lookout and had greatly increased the guard, placing them in batches of seven, about thirty feet apart,” remarked the Irishman. But the sentries were complacent. Perhaps they didn’t believe any raider would risk his life on this of all evenings.

“They were chattering,” recalled Mayne, as he and soldiers stole across the desert airstrip, placing their bombs on the same spot on every aircraft—on top of the wing above the fuel tank. Each bomb had a 30-minute fuze.

“We hadn’t quite finished when the first bomb went off,” said Mayne. “The Italians could see us in the light of the burning planes and began shouting, ‘Chi va la? [Who goes there]. It was the first time I’d ever been challenged, so I replied ‘freund.’” Although dazed and frightened, the Italians knew very well this imposing silhouette was no friend. “They began firing,” recounted Mayne. “But they didn’t hit us, and we just slipped through them in the dark.” Back at their base at Kabrit, 80 miles east of the Egyptian capital of Cairo, the raiders regaled the rest of the SAS with their accomplishment.

A Better commander?

Mayne was a natural warrior. He had the rare ability to process information and make the correct decisions in the blink of an eye. He was the officer with the golden touch—unlike the aristocratic British SAS commander, David Stirling, who had twice attempted to raid Sirte airfield, five miles east of Tamet, and had twice failed.

Mayne’s abilities in the field earned him his supervisor’s jealousy—a rivalry which would result in Stirling being captured, and Mayne rising as a talented military commander as leadership of the fledgling Special Forces unit fell upon his shoulders.

A champion boxer and international rugby player, Mayne had read law at Queen’s University in Belfast. Quick-witted as well as light-footed, his mind never fogged with panic even in moments of great stress.

His commander Stirling, by contrast, lacked nothing in courage or enthusiasm, but had none of Mayne’s physical or mental attributes. Clumsy, excitable and incautious, Stirling was unsuited to warfare by stealth.

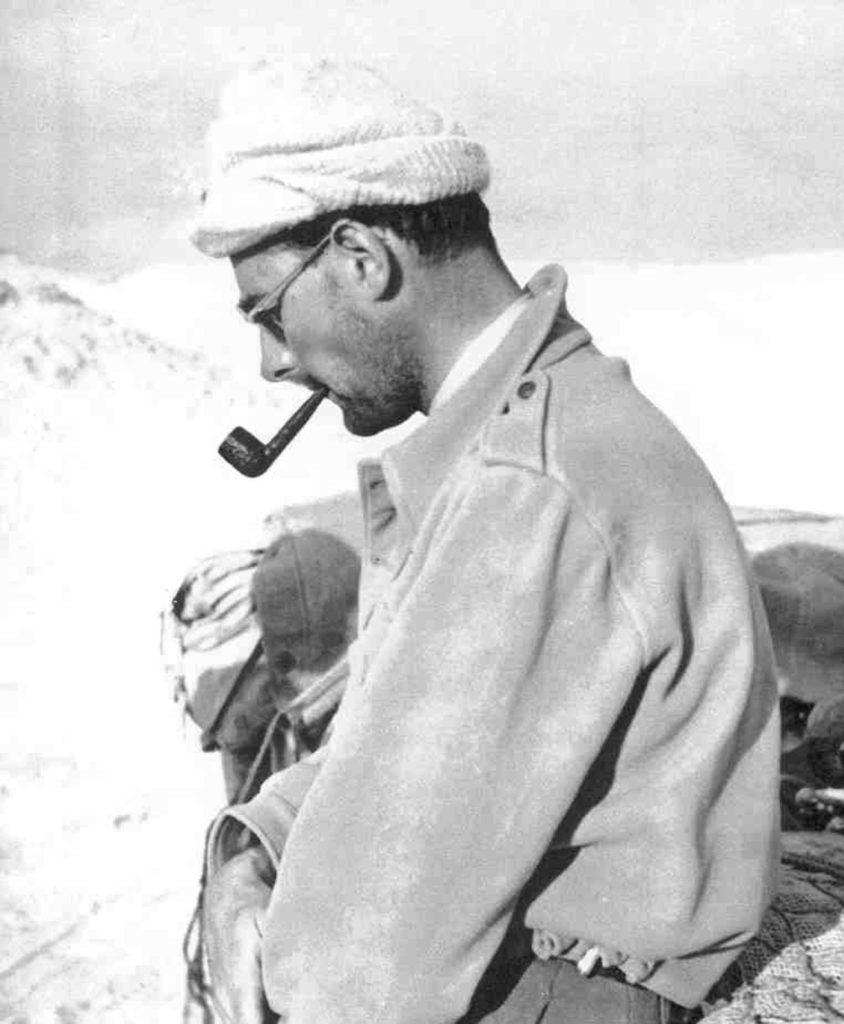

The navigator who brought Mayne and his raiders to Tamet airfield on the first raid was Mike Sadler, then serving in the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), an elite reconnaissance unit prized by the British for its prowess at deep desert exploration—and infiltration of enemy-held wilderness. Sadler transferred to the SAS in early 1942 and fought in its ranks for the rest of the war.

“Paddy felt his true vocation in war,” he remembered. “He was well suited to war and he enjoyed it. He was very good at fighting the Germans, but he was also a solicitor [lawyer] and a very able sort of chap.”

As the war in North Africa intensified in 1942, Mayne’s reputation as a guerrilla fighter grew. That summer the SAS took stock of a consignment of American Willys jeeps, liberating them from the LRDG, who for months had been ferrying the raiders to their targets.

The jeeps were Mayne’s idea.

Resentment and Envy

On one raid, at Sidi Haneish on the night of July 26, 18 of the vehicles drove onto the airfield and destroyed or damaged 30 Axis aircraft. In September the SAS was awarded regimental status, comprising an HQ squadron and four combat squadrons with a total strength of twenty-nine officers and 572 other ranks.

Promoted to major, Mayne took command of A Squadron. On Oct. 7 Mayne and his men left Kabrit in a fleet of jeeps and trucks for the Libyan desert with instructions to attack Axis lines of communication and ambush their motorised columns. Mayne thrived. “This sort of fighting was in his blood,” recalled the squadron’s Medical Officer, Capt. Malcolm Pleydell. “There was no give or take about his method of warfare, and he was out to kill when the opportunity presented itself.”

For two months Mayne and his men harried the Germans and Italians as they withdrew west across Libya from the frontline at El Alamein, chased by the British Eighth Army. The LRDG’s intelligence officer, Bill Kennedy Shaw, had a low opinion of Stirling but only respect for Mayne. “Stories of their operations used to reach us,” he said. “Tales of trains mined, railway stations wrecked, road traffic shot up and aircraft burned on their landing grounds.”

On Nov. 29 Mayne’s A Squadron rendezvoused with B Squadron at Bir Zalten, a remote spot about 80 miles inland from the Libyan coast.

Stirling was in command of B, defying orders from Middle East HQ in Cairo not to go on operations. He, too, had heard about A Squadron’s achievements—deepening his resentment and envy of Mayne.

Stirling intended to make a name for himself by taking B Squadron further west towards the Libyan capital of Tripoli, and perhaps even beyond into Tunisia.

Captured

It was Stirling’s fantasy to become the leader of the first unit from the Eighth Army to contact the British First Army as it advanced eastward from Algeria into northern Tunisia. That, he hoped, would prove to his detractors that he was the Irishman’s equal.

The two squadrons threw a party on the evening of Nov. 29 and parted the next day. It was the last time Mayne would see Stirling until after the war. On Jan. 24, 1943 Stirling and a 14-man patrol were surprised by the Germans as they slept in a Tunisian wadi. Three men, including Sadler, managed to escape.

One of the German paratroopers, Sgt. Heinrich Fugner, remarked how easy it had been to capture the British soldiers. “They had not posted any sentries,” explained Fugner. “Maybe they felt so safe in their hideout.” The German was also struck by Stirling’s “tired and exhausted state.”

According to one SAS officer, Capt. John Lodwick, the regiment descended into “chaos” in the immediate aftermath of Stirling’s capture. “A great and powerful organisation had been built up, but it had been an organisation controlled and directed by a single man,” commented Lodwick. “Stirling alone knew where everybody was, what they were doing, and what he subsequently intended them to do.”

When Mayne learned of Stirling’s capture in the middle of February, he was with his squadron in the Lebanon, undergoing skiing instruction in the expectation that 1SAS would be deployed in the mountains of the Balkans in the spring of 1943.

Mayne had travelled to the ski school still absorbing the news he’d received from Northern Ireland that his father had died. He was now the paternal head of his family, responsible for his mother, on whom he doted, and his six siblings.

Mayne most likely had conflicting emotions when he heard about Stirling. He had little respect or affection for his commanding officer. In a letter to one of his sisters the previous fall, Mayne told her that Stirling “is very apt to promise things that don’t happen.”

A Change in leadership

Yet the Irishman knew that for all Stirling’s flaws, he had not only the arrogance and charisma but also—thanks to his aristocratic background—the social standing and connections necessary to grow the budding SAS. “David was a very good organizer, had vast contacts and knew all the right people,” said Sadler.

Mayne, who came from a middle-class Irish family, was more at ease with the class below than the one above. At Kabrit he preferred to drink in the sergeants’ mess rather than share a glass with his fellow officers. In fact he had an antipathy towards most British upper-class officers. He had left the Scottish Commando after an altercation with his superior, Maj. Geoffrey Keyes, the son of the famous admiral and baronet (Roger, Lord Keyes), and kept his distance from upper-class officers recruited to the SAS by Stirling in 1942.

There was, however, one such officer for whom Mayne had a high regard, and that was David’s older brother, Bill. Four years older than David, Bill was his antithesis in character. A steady, reliable, well-rounded man, Bill provided much of the intellectual input to the SAS in its infancy in summer 1941. At the time he was working as an adviser to Lt-Gen. Arthur Smith, the Chief of Staff at Middle East HQ. Bill Stirling had been recalled from Cairo to Britain in November 1941, but a year later was appointed commanding officer of No62 Commando (which in May 1943 became 2SAS) and in February 1943 was sent to Kabrit to assess the future of 1SAS.

Following his brother’s capture, Bill Stirling’s assessment of the situation in Kabrit resulted in March 1943 in a reorganisation of the SAS, as well as the other numerous ‘private armies’ that had sprung up in North Africa. Mayne was appointed CO of 1SAS, which for the duration of 1943 was redesignated the Special Raiding Squadron.

Bill Stirling had faith in Mayne’s ability to command a regiment.

The Irishman had earned the respect—bordering on the reverence—of his men and also possessed what fellow SAS officer George Jellicoe described as “tactical genius.”

Jellicoe was given command of the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) and this unit, along with 1SAS and a Greek raiding squadron, came under the aegis of Raiding Forces, whose commander was Lt. Col. Henry ‘Harry’ Cator, a 46-year-old decorated veteran of the First World War. Cator was in effect the chief executive of Raiding Forces, responsible for logistics and administration.

Forging A New SAS

This freed up Mayne to focus on his regiment, many of whom had only recently joined the SAS. One new face was Lt. Peter Davis, who remarked: “As far as Raiding Forces Headquarters were concerned, they might just as well have not existed for all the effect they had on our training or our control. All decisions rested solely with Paddy.”

Like all newcomers to the SAS, Davis had heard tales of Mayne and his feats in battle, but still nothing prepared him for their first encounter in February 1943. He was stunned by Mayne’s “massiveness,” and recalled that, “his wrists were twice the size of those of a normal man, while his fists seemed to be as large as a polo ball.” Davis stared up at Mayne and trembled as “his piercing blue eyes looked discomfortingly at me, betraying his remarkable talent of being able to sum a person up within a minute of meeting him.”

Davis expected a voice and personality to match the imposing physique, but was surprised by quite the contrary. “I was struck by the incongruity of his voice and of his shy manner,” he recalled. “His voice was low and halting, with a musical singsong quality and the faintest tinge of an Irish brogue. I was soon to learn that when he was excited or intoxicated, this remarkable voice would become so Irish as to be hardly intelligible, and when he was angry it would reach such heights as to be almost a falsetto.”

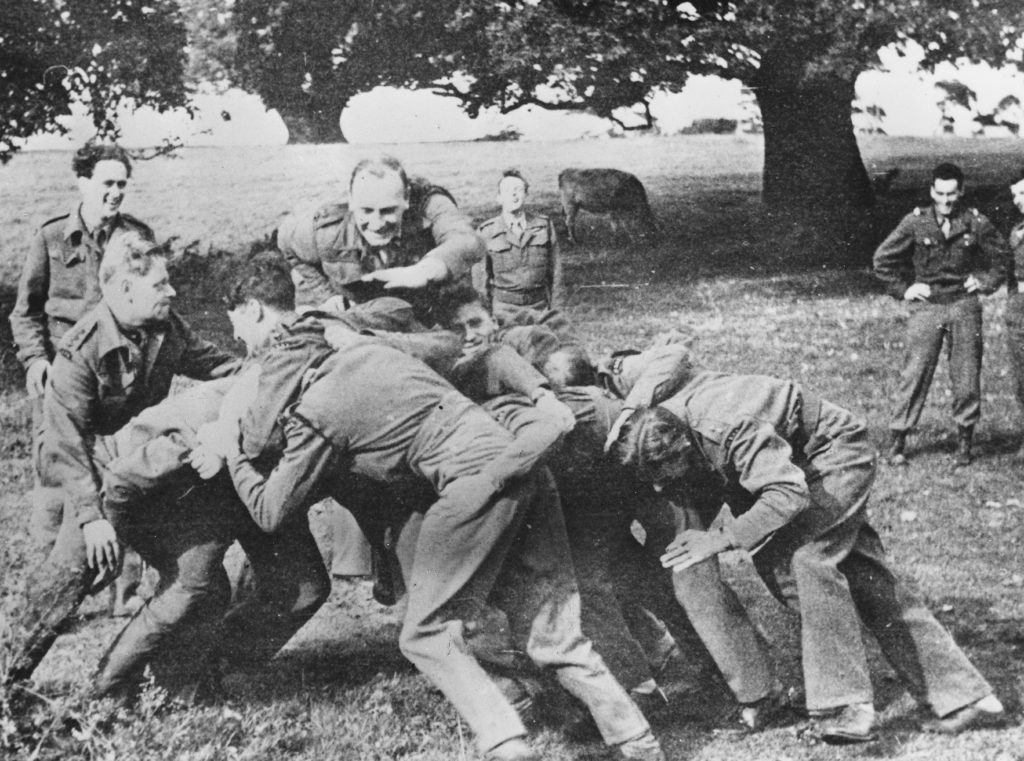

Mayne and his men moved to a new camp at Azzib in Palestine at the end of March. The new recruits soon discovered that Mayne was a man who did nothing by halves. At Kabrit he drank in the sergeants’ mess until 2 a.m., but would be the first to appear four hours later for physical training, fresh and full of energy for the 6 a.m. start.

Throughout spring 1943, he pushed his men relentlessly during training, while also expecting them to keep pace with his revelry. Mayne devised and oversaw the training program. He had his men schooled in the use of American and Axis weapons, light and heavy machine guns, and established a mortar section of one officer and 28 other ranks. He organized night exercises on the coastline from landing craft, and made sure the men received instruction in cliff scaling, wire-cutting and map-reading.

A Military Theorist

Mayne was a competitive animal, a man for whom sport was an essential part of his character. He cultivated a fierce rivalry between his three troops: One, Two and Three. This culminated in an exercise in late May in which each troop had to march from the banks of Lake Tiberias back to their coastal camp. “The distance was about 45 miles over rough and difficult country, and in the heat of the Palestine summer,” said Davis. It was a brutal march. Three Troop went first and only eight out of 60 completed the march within the designated time. One Troop erred in their map reading and took nearly 48 hours, while Two Troop endured all manner of agonies en route to Azzib.

The march achieved Mayne’s purpose of fostering not only competition within the SAS, but also strengthening camaraderie within each troop. Mayne was also growing during this time, maturing as a man and developing as an officer. In the first year of the SAS’s existence, he was able to display his physical prowess.

Now as commanding officer, he demonstrated his abilities as a military theorist. He divided each of the three troops into three sections, each one composed of approximately four officers and 70 men. These troops were then divided into two equal subsections under the command of an NCO. These subsections were further split into three parties of three-man specialists: a Bren gunner, a rifleman and a rifle-bomber.

Lt. Peter Davis, who commanded one of the sections in Two Troop, recalled that Mayne created “a highly efficient little fighting unit, capable of providing its own support in many of the usual situations which one expects to meet in battle.”

A small signal and engineers’ section was attached to each Troop. The organisation was in marked contrast to how the SAS had functioned under David Stirling; a year after forming the SAS, Stirling had not even raised its own signal section, relying instead on the LRDG’s signalers to their great irritation.

Assaulting Sicily

The SAS left Palestine for Suez on June 6 and for the rest of the month they practiced amphibious landings from LCAs in the Gulf of Aqaba and rehearsed neutralizing cliff-top gun batteries; they knew the real thing was imminent, and they guessed it would be somewhere on Sicily, but the exact objective remained a mystery.

On June 28, 1943, Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery inspected the SAS at Port Said in Egypt and expressed his confidence that it would achieve its objectives. The men then had a couple of days’ leave and most spent it in Cairo, enjoying the city’s many bars and restaurants.

Mayne had an altercation with Lt. Col. NGF Dunne, Provost Marshal of Cairo. Dunne’s nickname was “Punch,” suggesting he was also a pugnacious character who perhaps relished the chance to confront the legendary Mayne. Mayne had probably drunk too much during his unit’s final binge before departing on operations. The Irishman was taken into custody, which presented Lt. Col. Harry Cator with an awkward predicament. He explained the situation to his superior, Brig. George Davy, Director of Military Operations in Cairo, and secured the immediate release of Mayne. “Harry then brought the contrite Paddy into my office to apologize to me for causing so much trouble,” remembered Davy. “I thought that a bit unfair and turned the interview into a good laugh.”

The SAS sailed from Port Said on July 4. Once at sea, Mayne briefed his men on the actual target: a battery of four powerful guns situated on the southeast coast of Sicily on a promontory called Cape Murro di Porco [Cape of the Pig’s Snout]. It was imperative the battery was destroyed without delay in the early hours of July 10 for the main British invasion fleet would hove into view a few hours later.

Mayne explained that One Troop would launch a frontal attack on the battery with Two Troop swinging west and striking from the northern side. Three Troop would come ashore half a mile further west and strike inland to capture two farms to the rear of the batteries that were believed to be a barracks. Lt. Johnny Wiseman, a section leader in One Troop, led the SAS assault, moving inland through the dense scrub that lay between the rocky shore and the guns.

Guns and Lost Teeth

“We landed, got up the cliff and the area where the gun was, had barbed wire round it,” recalled Wiseman. “I got there first and we cut the wire. I thought it might be mined but it wasn’t so we went through a gap I’d cut and my troop took the first gun without any bother.”

Wiseman got on the radio to give Mayne a situation report but struggled to make himself understood to his CO. “I’d managed to lose my false teeth!” he remembered. His real teeth had been lost in a prewar sporting accident and his false ones had literally shot out of his mouth as he barked out orders. Wiseman eventually got his message across to Mayne…and also managed to find his false teeth as dawn broke.

The arrival of morning also helped the engineers section prepare the charges to destroy the battery. At 5:20 a.m., Mayne was informed that the guns were no more. He fired a green star rocket to signal to the invasion fleet that the coast was clear. But it wasn’t.

There was another battery, unknown to the SAS, approximately two miles northeast of the one just destroyed. It fired its first salvo as the SAS dozed in the morning light at one of the farmhouses seized by Three Troop. “We were roused by a sharp explosion from inland, which interrupted our peaceful reverie in the rudest way,” said Davis.

Mayne responded swiftly to the new threat, leading One and Two Troops towards the sounds of the guns, eliminating enemy pillboxes and other defensive positions as they moved northeast. The second battery was taken with the loss of just one man; in return the SAS had killed approximately 150 Italians and captured 500.

Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey, commander of XIII Corps into which the SAS was incorporated, hailed the destruction of the batteries as “a brilliant operation, brilliantly planned and brilliantly carried out.”

“Terribly Brave”

Two days later the SAS came ashore at Augusta, an important naval port 12 miles north of Cape Murro di Porco that the Eighth Army wanted as a base. Germans were on the high ground overlooking Augusta. The intrepid raiders were subjected to withering fire as they scrambled over rocks and into narrow streets that led into the town center. Sgt. Bill Deakins, in charge of engineer section, recalled that the one man who appeared indifferent to the incoming fire was Mayne, who strode down the street at the head of his men.

“He had one hand in his pocket, his cuffs—as was his habit—turned back and behind him trotted his signaller, David Danger,” said Deakins. “It was never done out of bravado but simply to give the men confidence.” Danger remembered Mayne as “terribly brave” but also a man who could be hard to the point of unfair if he disliked someone. “He could be tough in chucking out those he didn’t feel fitted.”

The SAS held Augusta. Mayne was awarded a bar to the Distinguished Service Order he had received in North Africa. It was a reward for the accomplishment of the two operations in Sicily. The citation praised his “courage, determination and superb leadership which proved the key to success.”

The SAS spent August at Cannizzaro, a suburb of Catania on Sicily’s east coast. Mayne established his HQ in the former home of a fascist doctor. His men slept outside in the courtyard and in the adjoining lemon grove. “We had many episodes with Paddy in Catania,” said Danger. “One night we had a party and we were all bedded down in the courtyard of this house. We didn’t have tents. Suddenly Paddy started pelting us with flowerpots and we had to take evasive action.”

Mayne gave life his all, whether it was partying, training or fighting.

A few days after boisterously showering his men with flowerpots, he raced them to the top of Mount Etna on a training exercise. “Average time to climb Etna from end of road, 2 3/4 hours,” recorded the SAS war diary. “Major Mayne, DSO, 2 hours.”

Beating a path Into Italy

On Sept. 1 the war diary noted that the SAS marched to Catania for embarkation. Their ultimate destination was Bagnara, a coastal town on the toe of the Italian boot, built at the foot of a steep hill. The main British invasion of Italy would be 11 miles south at Reggio. The SAS’s orders were to secure Bagnara and the road leading from the town up to the plateau far above.

The SAS operation was bedevilled by problems with the landing craft. It wasn’t until 4:45 a.m. on Sept. 4 that they were put ashore on Bagnara’s northern beach, two hours behind schedule. “No one knew if the beach was mined or not,” said Alf Dignum, a signaller. “Paddy Mayne was first up the beach, walking all the way, and by the time we’d followed him up there was still only one set of footprints.”

Mayne quickly realized they had landed on the wrong beach—the northern beach instead of the southern one. Standing on the broad promenade at Bagnara, a popular vacation spot before the war, he coolly issued instructions to his men. He gave Two Troop the task of moving inland through the sharply ascending streets to secure a road bridge.

Cpl. Sid Payne of Two Troop was last man but one as his section moved in single file through the town in their rubber-soled boots. “The chappie behind me tapped me on the shoulder, pointed to his ear, then down the road,” remembered Payne. “I could hear marching. So I tapped the bloke in front of me and signalled to him, and we all spread out on the road and round this bend came the first ranks of this column of Germans, carrying their rifles at ease.”

The Germans were engineers, sent to Bagnara to blow the bridge after news broke of the main Allied landing. “They got quite a surprise,” said Payne. Most of the engineers were killed or wounded in the initial ambush. Those that weren’t fled out of town. There was sporadic fighting throughout the day against the Germans dug in among the terraced vines overlooking Bagnara.

At daylight on Sept. 5, the British 15 Brigade began pouring into Bagnara. Then a cruiser appeared and shelled the Germans on the hillside. By dusk on Sept. 5 the Germans had fled and the SAS had secured yet another objective. Five men were killed at Bagnara and a further 16 wounded.

A month later at Termoli, a port on the east coast of Italy, the SAS lost 20 men and a further 22 were captured. It was a battle that the SAS shouldn’t have fought, being one more suited to the infantry as opposed to highly-trained but lightly-armed commando force.

Who Trains Wins

Nonetheless, Mayne and his men distinguished themselves by dint of their courage and steadfastness. On Oct. 10, 1943, Dempsey addressed the SAS at their billet in Termoli, praising them for what they had achieved in Sicily and Italy. “In all my military career,” he said, “I have never yet met a unit in which I had such confidence as I have in yours.”

Dempsey then listed the reasons for the success of SAS, all of which were proudly recorded in the war diary: 1) Well Trained, 2) Fit, 3) Discipline as a unit and as individuals, 4) Careful planning but no over confidence, 5) Long experience of fighting, 6) Spirit.

In short, they were men who had been molded by Mayne in his own image. Not so much ‘Who Dares Wins,’ the gung-ho SAS motto devised by David Stirling in 1941, but Who Trains Wins. This philosophy continued to underpin Mayne’s command in 1944 when the regiment returned to the UK. The SAS expanded into a brigade, comprising 1 and 2SAS, two French regiments and a Belgian company. 1SAS operated behind Nazi lines in Occupied France throughout the summer of 1944, and Mayne received a second bar to his DSO.

In April 1945 Mayne led his regiment into Germany, and was recommended for Britain’s highest gallantry honor, the Victoria Cross, for rescuing some of his men under heavy enemy fire. The medal never materialized and Mayne instead received a third bar to his DSO.

Ten years later he was dead, killed in a car crash in his native Northern Ireland. “It may seem a strange fate that Col. Blair Mayne should have survived so many hazards as a soldier, and at 40 lose his life in a motor accident,” remarked the Belfast Telegraph in its Dec. 14, 1955 edition. “But he lived hard in peace, as well as in war…Men like him are made for conflict.”