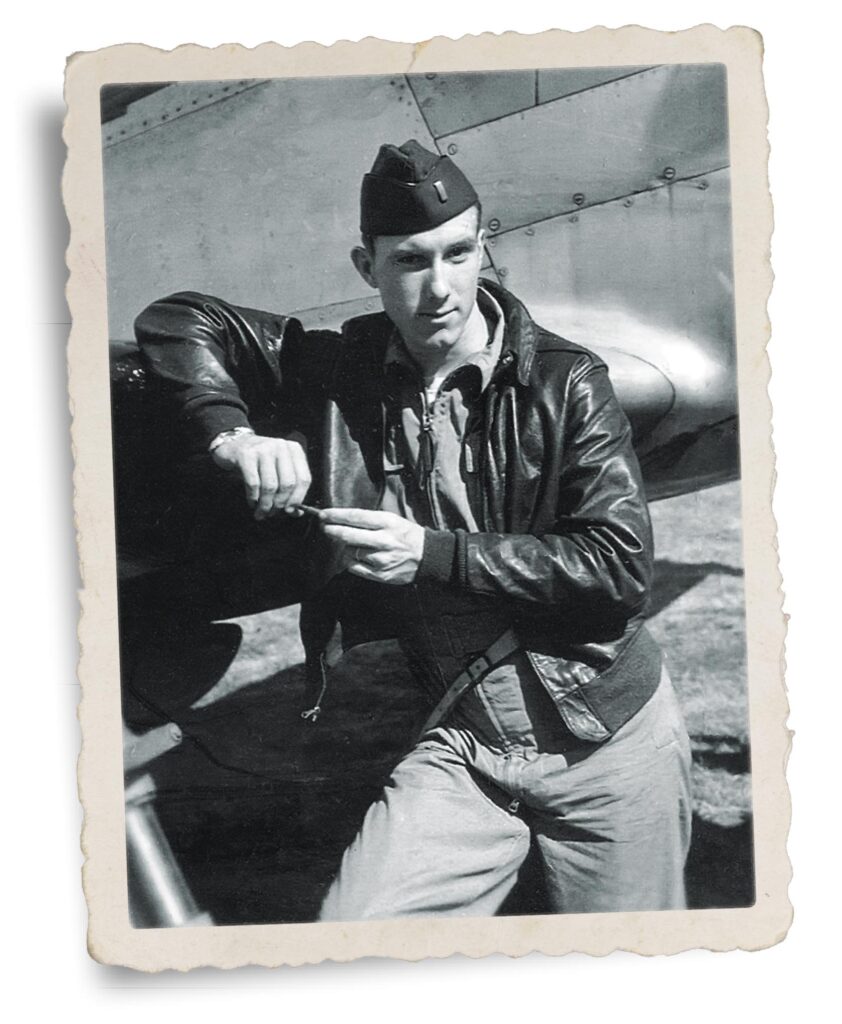

In the spring of 1945, Wally King was a young lieutenant flying a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt over Germany. During King’s last combat mission, his plane was hit by flak and he bailed out over enemy territory. He survived the last few weeks of World War II in captivity but was able to return home, raise a family, and start a successful career as a CPA, eventually owning one of the largest accounting firms in Pittsburgh. Today, the 99-year-old veteran serves as a volunteer for the Meals on Wheels program, visiting shut-ins and the infirm near his home in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. The active almost-centenarian spoke with World War II about his military career.

How did you end up in the army?

I turned 18 and graduated high school in 1942 in my hometown in Ohio. I went to the recruiting office and said I wanted to be a pilot. He said, “Let me sign you up and then once you’re in the army, you can ask to go for pilot training.”

Well, I didn’t fall for that. So they told me to go to Cleveland to apply for pilot training. I was called up for active duty in January 1943 and went through basic training.

I trained on P-40s in Tallahassee, Florida. Nice solid airplane, but certainly way behind other aircraft by that time. Then I shipped over to England in 1944 and went to Goxhill airfield on the North Sea to fly the P-51. Probably got about 30 hours in the air there. Then, after D-Day they flew us over to A-1 Airfield behind Utah Beach. I was assigned to the 363rd Fighter Group.

A few days later, the army deactivated the unit because they needed more photo reconnaissance. We could stay with Mustangs that had cameras in their bellies or transfer to fighter groups, which is what we did. I went to Le Mans and joined the 513th Squadron of the 406th Fighter Group in the Ninth Air Force. The operations officer took me out to a P-47 Thunderbolt for a cockpit check and then told me to fly it. The next day I flew my first combat mission.

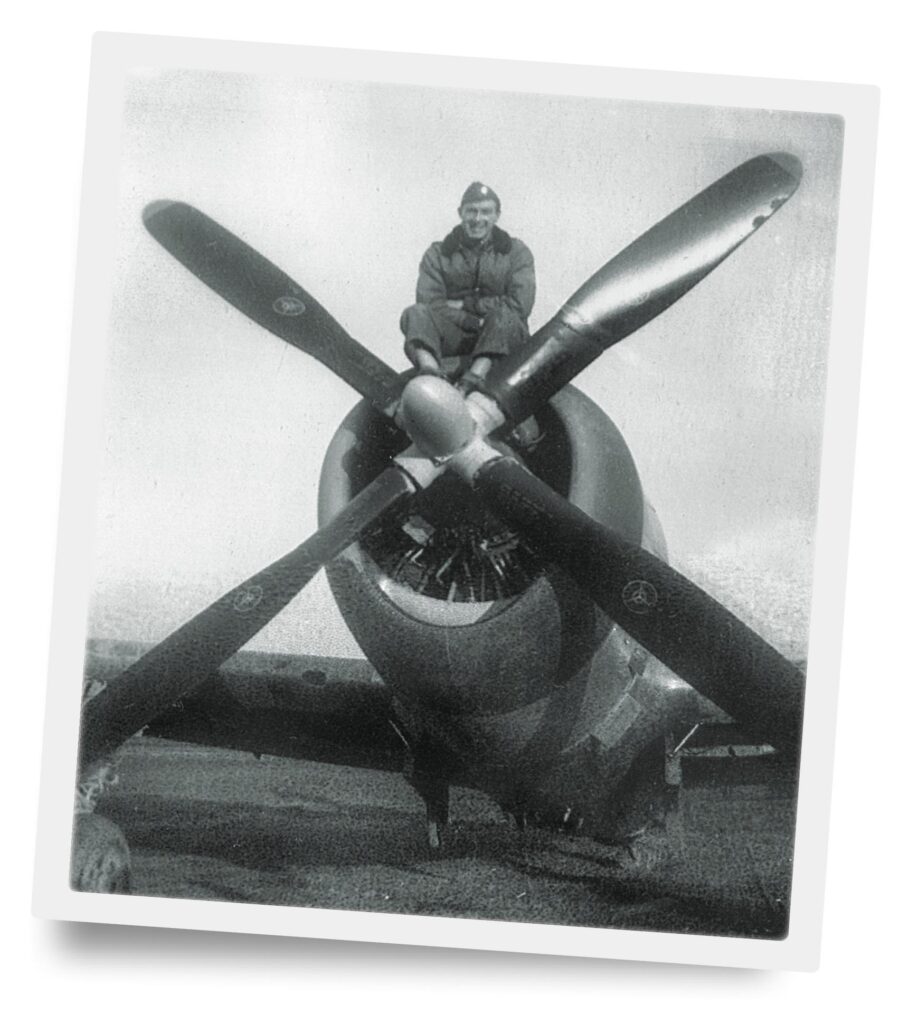

How did the P-47 compare to the P-51?

The Thunderbolt was a totally different airplane than the Mustang. It was much easier to fly. The P-47 was also a better ground-support airplane. It was a very honest fighter that didn’t have any quirky habits and could take a lot of punishment. One time, we hit a German night fighter field. I was flying low and looked over to my wingman, who was going down this concrete runway. I could see this fire on the end of his propeller. He was grinding it on the concrete! About five inches of his blade was gone. I never really had any major damage on the missions that I flew, except for the last one. The P-47 was a durable, tough machine.

You flew 75 missions during the war. What type of action did you experience?

Most of the time, we would fly along the battlefield and look for enemy vehicles. After the Falaise Gap [in mid-August 1944], the Germans were afraid to move because they would get strafed. We rarely saw vehicles on the road. Never saw many tanks. I did see a couple of Tigers, but we didn’t have anything that would damage them. If they were on a hard surface road, we would strafe the back of it and bounce the bullets up underneath to the fuel tanks. I did that once but can’t say it was effective.

Our targets were mostly marshaling yards, rail traffic, road bridges, and just cutting railroad lines. We’d send one plane down and drop bombs to blow the railroad tracks, then send another one a few miles away to do the same thing.

The most memorable mission was when the Ardennes Offensive began [on December 16, 1944]. Our group provided air cover during the Battle of the Bulge. We hadn’t flown for a week or more until the weather cleared a couple of days before Christmas. Our goal was to quiet the flak before air drops of supplies were made around Bastogne. We couldn’t see anything because of the snow cover, so we bombed, fired rockets, and strafed the woods. Once the C-47 Dakotas pushed out supplies, a whole army of ants appeared out of the white snow. These guys had been dug in and started dragging those supplies into town.

What other missions did you fly?

Our squadron had the undesirable task of beating up flak before a parachute drop on the Rhine River near Wesel in March 1945. When we saw the line of transport planes coming, we went down to make a strafing pass. As I was coming up, the C-47s had already started dropping their people. A paratrooper went right over my wing! I thought, “This is suicide!” It looked like Dante’s Inferno. These C-47s were burning, they had engines out, paratroopers were being dropped in the river, gliders were crashing and, of course, the air was filled with flak. It looked to me like a colossal failure, but it wasn’t. They got pontoon bridges over the river and the tanks went across.

Let’s talk about your last mission, which you were told would be your last.

They called for an eight-plane mission on April 18, 1945. I was leading the second flight. I said to the squadron commander, “This is my 75th mission. Don’t you think it’s time to quit?” He said, “Yeah. This is going to be your last mission.” Little did I know!

The army had reached the Elbe River and crossed over just south of Magdeburg. We were looking for targets of opportunity. On our way home, my wingman spotted a cannon on a railroad car and wanted to go after it. So we buzzed down to take a look.

I was pretty low but I wasn’t strafing. All of a sudden, there was a boom. I knew I had been hit in the engine by flak. Soon, fire was coming over the windshield. I looked down at my feet and saw the armor plate in front of the cockpit was melting. I said, “Time to go, Wally!” I was like a cork out of a bottle! The chute opened and I was upside down. I got myself upright and I heard this noise whizzing by. I thought it was bees. It was civilians shooting rifles! I started swaying to make myself a poor target. I drifted over this house into the backyard. I got down and could see the Elbe River. I thought maybe I could float downstream to an American bridge. I’d gone about 100 yards toward the river when this little boy tripped me. Then these guys showed up with rifles. I just put my hands up and surrendered. They took me into the house where a medic started working on me. I had burns on my face, a broken wrist, and a bad ankle.

Then two German soldiers came in. They smashed me across the side with their guns and knocked me off a stool I was sitting on. They hauled me out into the yard where the civilians started beating me. I’m pretty terrified. I am in the toughest situation of my life and I’ve never even thought about God. Once I said that, the most sublime peace settled over me. I felt God had come to take me home. That sense stayed with me for the two weeks I was a prisoner. Whatever happened to me was going to be all right.

The soldiers took me to a bunker, where this big, burly noncom was going to rearrange my teeth. A German officer just shoved him and started screaming. From what I could get, he was saying, “Would you like our pilots to be treated this way?”

It wasn’t long before a Mercedes staff car pulled up with two Wehrmacht officers. They brought me to a major, who looked like he had just walked off a movie set. There was all this destruction everywhere and he was dressed immaculately. He started asking me ques-tions and I answered name, rank, and serial number. Just then the door banged open and in comes a Luftwaffe major, who was also immaculately dressed. They started shouting at each other. I knew what it was about. The Wehrmacht had no authority to hold American airmen. He was supposed to turn me over to the Luftwaffe.

So the Luftwaffe major took me to a dispensary where a medic starts working on me. He says, “You’re a lucky guy. The people in that village killed a bomber crew yesterday.”

A few days later, we evacuated the building. They took me to a house near the Russian front where other Americans were being treated. I was there for nearly two weeks and had little food. There were several American patients, but most were unconscious. An American captain told me he wanted to take these guys to a bridgehead about 40 miles away because no one was caring for them. Somehow, he found a couple of ambulances with fuel. So off we went with a German doctor and these other German soldiers, who had surrendered since the war was all but over now.

We made it to this castle, which looked like something you’d see at Disneyland. A lady came down and handed us keys to the fruit cellar. She said if the Russians get close, we should destroy all the food. This German officer said, “The Russians are close enough. Let’s eat!” So they made this big meal, which was the first real food I had had in two weeks. Then I found a bed in the castle—the biggest I had ever seen in my life—and went to sleep.

The next day, we headed for the American lines. Because of the German soldiers, we avoided the SS since they would kill these men for surrendering. We left after dark with no lights. American soldiers on a Jeep with a .50-caliber machine gun found us and guided us the rest of the way. We kept stopping so they could drag anti-tank mines off the road. We finally got there and they took me to the medical tent. They cleaned me up and took care of my burns and injuries. The next day, I was flown out with other burn patients to a hospital in France. I was there for about eight weeks. They finally sent me home on a Liberty ship loaded with cargo, tanks, and halftracks.

You went back to Europe last year as part of a Normandy tour. What was that like?

Delta flew us on a charter right to the beachhead—the first commercial airliner ever to land there. I wanted to find A-1, the first airstrip I landed at with the Mustang. I was near Sainte-Mère-Église, behind Utah Beach. My guide and I went to look for the airstrip. It was almost dark and we were about to give up when I spotted this monument. It said this was the site of A-1. I walked up this road that could have been the runway. I felt like I had been there before. It was a strange feeling standing on that spot where I had been 78 years ago.

You talk to groups about your experiences. What do you tell them?

I’m not a rah-rah-boy-we-won-the-war type of guy. I tell them that war is a nasty, dirty, evil business. There is nothing glamorous or glorious about war. I also tell them not all Germans were bad guys. That German doctor risked his own life for the Americans in his care. I wonder how many of those wounded guys would have made it if not for him.

I’m troubled by the fact that the U.S. college students and the high school students know nothing about World War II. Contrast that with France. We visited a school there and they were so engaged. They knew their history and asked intelligent questions. The headmaster asked the last question: “What advice do you have for these students?” I said, “Put down your cell phones and love one another.”