How the emperor of hoopla

got his start at scamming

PHINEAS TAYLOR BARNUM was a salesman and a showman, a hustler and a huckster. He sold Bibles for a while but he made more money selling tickets to see a mermaid that was actually the tail of a fish to a female orangutan’s torso with a baboon’s head affixed.

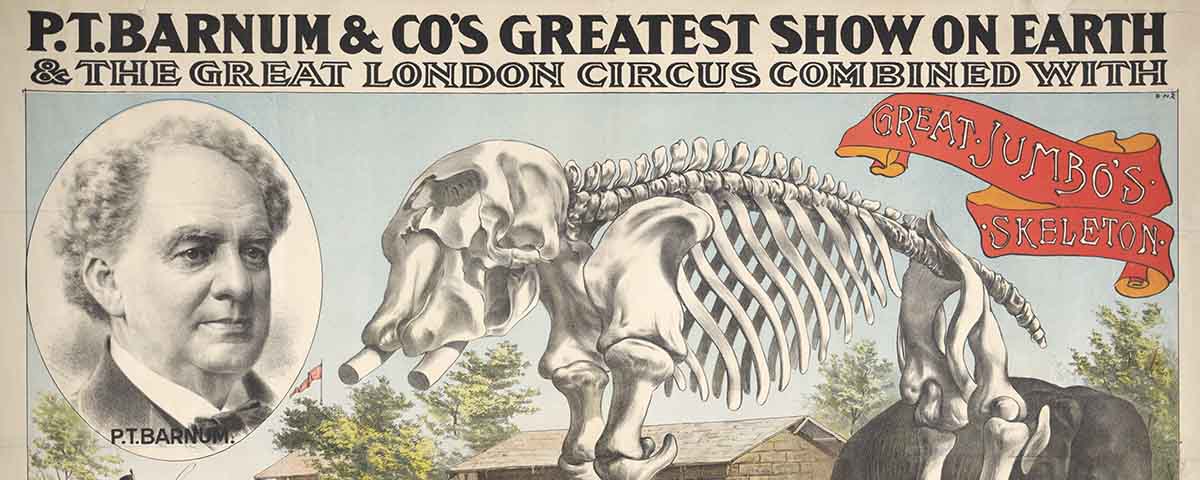

Barnum created his era’s most popular museum and most successful circus. He invented the moving billboard, the outdoor spotlight, and the baby beauty pageant. He pioneered the freak show and the sideshow, exhibiting midgets and giants, bearded ladies and fat ladies, an armless boy and a legless man, not to mention the famous “Wild Men of Borneo,” who were actually two dwarfs from Ohio.

Barnum invented the cross-country musical megatour, transforming a Swedish singer named Jenny Lind—unknown in America—into a must-see songbird who enriched both singer and impresario. He invented the celebrity wedding, arranging a ceremony for Tom Thumb and Lavinia Warren, midgets appearing at his New York museum, followed by a lavish reception for 2,000. Then he sent the newlyweds to the White House for another reception, this one hosted by President Abraham Lincoln.

Barnum wrote one of America’s first celebrity autobiographies. Then he wrote a second. And a third. All told, his multiple memoirs sold over a million copies. In 1880, a century before Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, Barnum pioneered the celebrity how-to-get-rich book, writing The Art of Money-Getting.

Barnum was a genius of hype, a wizard of advertising, a virtuoso of promotion, self- and otherwise. He was a walking, talking exclamation point who plastered his name and face on nearly everything he created, including a circus poster touting himself as “The Sun of the Amusement World From Which All Lesser Luminaries Borrow Light.”

“Barnum,” wrote historian Luc Sante, “embodied a unique combination of the showman, the preacher, the con artist, the speculator and the politician—the epitome of his era and a model for future generations.”

Barnum was the founding father of American pop culture, a commodity he exported, turning showbiz into a global industry.

But before all that—in 1835, as a curly-haired, baby-faced fellow of 25—Phineas Barnum began his career with a hoax so outrageous it later embarrassed even him. This foundational scam, involving George Washington and an elderly Negro slave, illustrates Barnum’s guile, humor, skill at media manipulation, and ability to tiptoe to the outer edge of decency—and gallop on, giggling all the way.

***

In the summer of 1835, P.T. Barnum was restless. A few years earlier, he’d been a success in his native Bethel, Connecticut, running a lucrative lottery and publishing a weekly newspaper in which he lambasted politicians and clergymen, particularly those who advocated banning lotteries. In 1832, a libel conviction landed him in jail for 60 days. When he emerged from the hoosegow, supporters cheered him. But cheers couldn’t pay his bills and in 1834, under pressure from its clergy, Connecticut outlawed lotteries. Barnum moved his wife and daughter to Manhattan and opened a grocery store at 156 South Street. The business paid his bills but he longed for something more lucrative, more exciting—a new hustle.

He found one in the summer of 1835. A friend mentioned that he’d recently sold his share in a remarkable property—161-year-old Joice Heth, said to have been in her days as a late-middle-aged slave George Washington’s childhood nurse. Now featured at Philadelphia’s Masonic Hall, Heth was drawing crowds of paying gawkers, but her promoter had tired of show business and wanted to sell the rights to display her.

The story was preposterous—161 years old? George Washington’s nurse?—but Barnum’s pal produced a clipping of a Philadelphia newspaper article characterizing Heth as “one of the greatest natural curiosities ever witnessed.” Barnum listened, intrigued. Hearing money and sensing fun, he traveled to Philadelphia to see this wonder.

Sprawled on a couch in Masonic Hall, Heth resembled a living mummy. Wizened, wrinkled, toothless and blind, weighing barely 50 pounds, with a wild thatch of white hair, the ancient black woman seemed, Barnum recalled, “far older than her age as advertised.” She could barely move—her left arm and both legs were paralyzed—but she could talk. She told stories about “dear little George” and occasionally broke into song, croaking Baptist hymns.

“She was pert and sociable,” Barnum noted. He asked R.W. Lindsay about buying the rights to exhibit Heth, provided Lindsay could prove she was as advertised. Lindsay showed him a bill of sale, dated February 5, 1727, stating that Augustine Washington—father of the father of our country—agreed to sell a neighbor “one negro woman, named Joice Heth, aged fifty-four years.” The price: 33 pounds.

“The evidence seemed authentic,” Barnum later wrote. Maybe, but Barnum, who was not one to let facts interfere with a good yarn, also wrote later that he himself had forged that bill of sale, marinating the document in tobacco juice to simulate antiquity. Both tales are probably bogus: Lindsay had been exhibiting the dubious bill of sale for months, and Barnum simply seems to have recognized that the paperwork was good enough to gull rubes into paying to see Heth.

Lindsay wanted $3,000; Barnum dickered him down to $1,000. It isn’t clear if Barnum was actually buying the slave, as he claimed in his 1855 memoir, or merely buying the right to exhibit her, as he claimed in his 1869 autobiography. Either way, he paid $500 on the spot and borrowed the balance, putting his store as collateral. Then he brought Heth to New York. He had bet the family’s business on the old girl. Now he had to make her a star.

***

Barnum contracted to exhibit Joice Heth on Broadway in Niblo’s Garden, the city’s most elegant entertainment emporium. He bought Heth a dress and hired a woodcut artist to portray her on a poster he hung all over town, along with heaps of hype touting “the most astonishing and interesting curiosity in the world,” and “nurse to Gen. George Washington” and “the first person to put clothes on the unconscious infant who was destined to lead our heroic fathers to glory, to victory, to freedom.”

Barnum liked that line about dressing the baby Washington—he figured it would entice women to buy tickets—but worried about New York’s newspapers. If they exposed Heth as a fraud, he’d be ruined. But he guessed that newspapermen’s love of money would overpower their love of truth. He made the rounds of newspaper business offices, offering to buy ads in exchange for puff pieces.

Most publishers went for the bait, so he invited them to a pre-opening encounter with his marvel. Heth charmed the gentlemen of the press with stories that Barnum had taught her, including the familiar legend of young George and the cherry tree, which she identified as a peach. Reporters responded with crowd-pulling enthusiasm.

“A greater object of marvel and curiosity has never presented itself,” the New York Sun reported.

“The old creature is said to be 161 years of age,” said the Courier and Advertiser, “and we see no reason to doubt it.”

“She will be a greater star than any other performer of the present day,” the Evening Star predicted.

The Star was right. New Yorkers lined up outside Niblo’s by the score, eager to pay a quarter (today, $6.50) to eyeball the blind crone. She lay on a couch as customers strolled past her, some pausing to ask questions. Many had never seen a black person up close; some felt her hair and rubbed her leathery skin. Some wanted to shake the hand that had washed Washington. Others mumbled prayers. A few took Heth’s pulse, finding it strong and steady.

How did the star attraction feel about all this? Nobody knows. If Heth resented her role, she didn’t show it. Instead, she smiled, told stories about “little Georgie,” sang hymns, smoked her pipe, and appeared to enjoy herself. Barnum kept her spirits high with dollops of whiskey, later praising her as an “excellent actress” who was “always ready for fun.” Obviously, Heth knew she’d never nursed George Washington. Perhaps she enjoyed fooling white folks. She certainly exhibited a sly wit. When a visitor asked what she planned to do with her earnings, she replied, “Buy a wedding dress.”

“Whom do you intend to marry?” the man asked.

“Yourself, sir—if I can find no one else.”

Originally booked for three days at Niblo’s, Heth spent two weeks on display eight hours a day six days a week. Barnum claimed to be making $1,500 a week—today, $40,000. David L. Rogers, a prominent surgeon, asked if, when the old woman died, he could perform an autopsy in hopes of discovering the secret of her amazing longevity. Barnum put off Roger’s request; his star was still alive and he was about to take her on the road. Success and notoriety had the young showman feeling cocky: If he could scam sophisticated New Yorkers, he’d have no trouble rooking the rubes in New England.

He was wrong. “Suddenly, I found a difficulty which I had not foreseen, and which threatened to turn all my milk sour,” he wrote afterwards.

***

Barnum had overlooked the abolitionists.

In 1835, the anti-slavery movement was tiny and weak, especially in New York, with its deep financial ties to the cotton industry. But in New England, abolitionism was growing. William Lloyd Garrison began publishing his newspaper, The Liberator, in Massachusetts in 1831, and a year later, helped form the New England Anti-Slavery Society.

The Joice Heth tour’s first stop was Providence, Rhode Island, where abolitionist preachers told congregants it was immoral to pay money to gawk at a slave. “My attendance fell off,” Barnum recalled. “The priest-ridden people, under the anathemas of the clergy, came no more.”

Barnum detested preachers. First they’d convinced Connecticut to ban lotteries, now they were spoiling his latest hustle. “I hated the priests with a Carthaginian hatred,” he wrote. He knew he couldn’t out-fight the clergy; he had to outsmart them. He told the Providence Journal that he, too, was an abolitionist, and that Heth was a freedwoman touring to raise money to buy her great-grandchildren out of bondage. It was bunkum but it worked. Now preachers urged their flocks to see Heth; soon, the Journal reported that the exhibit’s stand had been extended a week due to “immense crowds of persons who have visited Joice.”

Boston was next. Barnum wrote to ministers there, inviting them to meet Heth. Several did, and she corroborated Barnum’s palaver about purchasing her enslaved descendants’ freedom. Why? Maybe Barnum forced her. Maybe she believed he would free her kin. Maybe she shared his love of a scam. Or maybe she simply realized that posing as George Washington’s nurse was the best job available to a crippled, blind, elderly black woman, slave or free.

Barnum later admitted he never bought any slave’s freedom, and bragged that one Boston minister handed him $10 to help liberate Heth’s kin. “I took the money, I could not do less without betraying myself,” he wrote. “That night, a few friends and myself spent it on Champagne and oysters.”

***

In Boston, Barnum presented Heth at prestigious Concert Hall where, in a smaller room, a chess-playing automaton was drawing crowds. The contraption was a cabinet topped with a wooden figure of a turban-wearing Turk. When enough customers gathered, the operator opened the cabinet to reveal countless gears and levers, then asked if anyone dared challenge the wooden Turk at chess. When a volunteer emerged, the operator turned a key and the Turk’s hand reached forward to make a move. The automaton nearly always won—but how? A connoisseur of chicanery, the sharp-eyed Barnum realized that a small man with a strong chess game had to be hiding inside. He loved the automaton and felt proud that his own humbug was outdrawing it.

But after three weeks, Heth’s box office began to dwindle. Barnum got an idea: Inspired by the Turk, he wrote to Beantown newspapers, attacking his own exhibit as a hoax. “Joice Heth is not a human being,” the anonymous letter said. “What purports to be a remarkably old woman is simply a curiously constructed automaton, made up of whalebone, India rubber and numberless springs…”

The double-reverse hornswoggle worked. “Hundreds who had not visited Joice Heth were now anxious to see the curious automaton,” Barnum wrote, “while many who had seen her were equally desirous of a second look, in order to determine whether or not they had been deceived.”

From Boston, Barnum ran Heth through Lowell, Hingham, Worcester, Springfield, and Hartford, Connecticut, before bringing her back to Niblo’s. The show had hit the road again around Connecticut when, on February 19, 1836, in New Haven, Heth spoiled Barnum’s fun by dying. “The old woman had kicked the bucket,” Barnum wrote. “I could humbug the world no longer.”

But Barnum’s mind kept churning out new humbugs. First, he considered keeping Joice Heth’s demise secret and taking a stand-in to England, where nobody would notice the difference. Then he remembered the morbidly curious Dr. Rogers and his interest in autopsying Joice. Barnum booked a Broadway theater, the City Saloon, and arranged for the surgeon to perform the autopsy onstage. To watch the procedure would cost 50 cents a head—twice what gapers had been paying to see Heth alive.

Nearly 1,500 customers watched attendants place Heth’s body on an examination table. Rogers, suitably gowned, announced to the crowd that he would be searching for signs of ossification—the hardening of internal organs observed in the remains of the extremely elderly. He sliced open the cadaver, sawing through the chest and skull and examining the liver, lungs, heart and brain, concluding that only minor ossification had occurred. “Joice Heth could not have been more than 75 or, at the utmost, 80 years of age,” Rogers announced.

Only one newspaper, the Sun, covered the event. The next day, a headline read: “Dissection of Joice Heth—Precious Humbug Exposed.” Even at 80, Heth couldn’t have nursed an infant George Washington born in 1732. Her stories of “little Georgie” were hokum, no doubt concocted by her exhibitor. “It is probable,” the Sun concluded, “that $10,000 have been made from this, the most precious humbug of modern times.”

Exposed as a con artist, your average hustler might slip quietly away. But P.T. Barnum was not your average hustler and he had yet another idea. He and assistant Levi Lyman called on James Gordon Bennett, the Herald’s feisty editor. Speaking confidentially, Barnum told Bennett, who detested his rivals at the Sun, that the autopsy had been a sham. Heth was still alive. Dr. Rogers had actually dissected Aunt Nelly, an obscure and recently deceased New Yorker, Barnum said.

Of course, Bennett published the story. “Joice Heth is not dead,” the Herald trumpeted. “On Wednesday last, as we learned from the best authority, she was living at Hebron, in Connecticut.” The Sun had been snookered, the Herald reported, along with those hundreds who paid to watch the autopsy. “Such is the true version of the hoax, as given to us by good authority.”

What a world. Thousands of New Yorkers had paid to see Joice Heth, alive and dead. Now the Sun was saying Joice Heth was dead—at age 80—while the Herald was reporting that she was still alive. And the Star was claiming that Heth was indeed dead and indeed had been 161 years old.

Showbiz sure was more fun than selling groceries. “I had at last found my true vocation,” Barnum wrote.

***

Barnum plied that vocation until his death in 1891, gleefully exhibiting midgets and elephants, black swans and horned frogs, Siamese twins and circus acrobats, freaks and phrenologists—and “A Curious Mortuary Memorial to Washington and Lincoln, Ten Feet High and Composed of Over Two Million Sea Shells.” And much, much more!

In his later years—when Barnum had grown rich and respectable and morphed into a temperance crusader and Christian pamphleteer who ballyhooed his attractions as “Moral Dramas”—his Heth hoax embarrassed him. “The least deserving of all my efforts,” he called his first triumph, and he maintained steadfastly that he, too, had been bamboozled into thinking that bill of sale was genuine.

That was malarkey. Writing about Heth in the New York Atlas in 1841, Barnum boasted of bribing reporters, buying Champagne with money donated to buy slaves’ freedom, and selling tickets to the theatrical autopsy. He even confessed to forging that bill of sale—although he certainly hadn’t. He reveled in his knack for con games, gloried in his gift for grift, flaunted his skill at fleecing the multitudes.

“Crown me with fame—erect a monument to my memory—decree me a Roman triumph,” P.T. Barnum wrote. “I deserve all—I stand alone—I have no equal—no rival—I am the king of Humbug.”

___

Peter Carlson (“Becoming Barnum”), who writes American Schemers, is the author of three books on American history—Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood, K Blows Top, a non-fiction picaresque about Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s 1959 tour of America, and Junius And Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy. A former reporter and columnist for The Washington Post, he is writing a memoir of his misspent youth.