I’ve been fascinated by aviation and photography since an early age. I knew I had to make flying part of my life after my first flight in an amphibious aircraft when I was 9 years old. A neighbor in my hometown of Brownsville, Pa., helped me build my first photo lab at age 12. When the Korean War broke out I was 18 and my draft card said “1A,” so I enlisted in the U.S. Navy, figuring it meant hot showers, hot food and the prospect of relative safety.

After taking written aptitude tests, I was told I qualified for naval aviation cadet training, but due to my stuttering (“By the time you asked for landing instructions,” the officer said, “you would be out of gas!”) I was sent to Naval Air Station Memphis as an airman apprentice. While at NAS Memphis I sought and was granted a place in the base photo lab in preparation for attending photo school at the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Pensacola, Fla., in September 1951. There I learned how to take oblique photos and studied mapmaking during the aerial phase, after which I returned to Memphis for classes to become a combat aircrewman.

Assigned after training to the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, I reported for aviation photography duty on April 1, 1953, and said I wanted to be stationed on the flight deck in the “hottest spot” they had. My senior petty officer, Aviation Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Victor Strickland, put me aft of the carrier “island” and all the way at the end of the deck on a catwalk, directly across from the landing signal officer (LSO)—the hot spot! It wasn’t long before that plum position paid off.

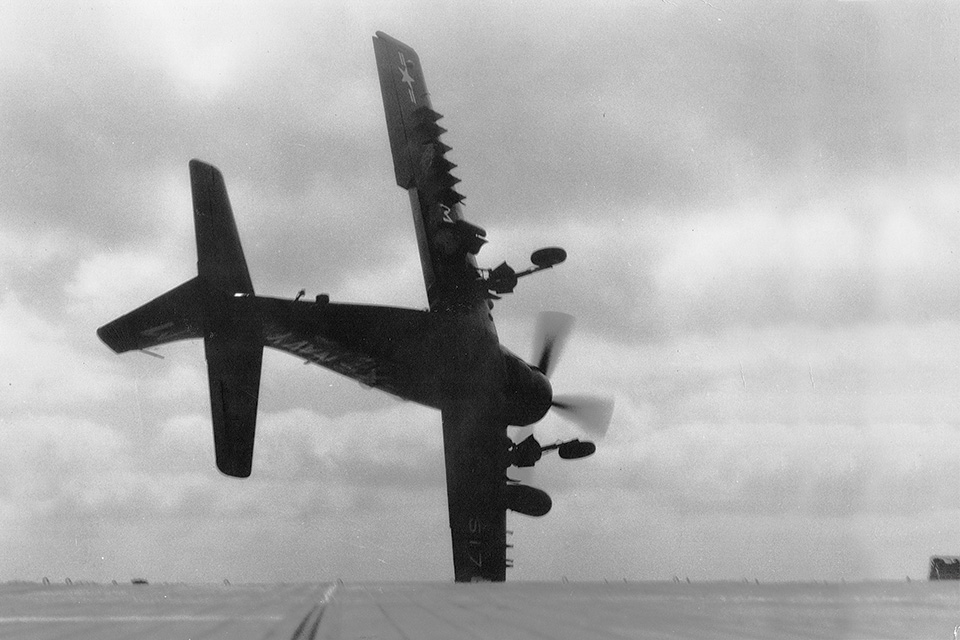

On April 8 my first opportunity to show what I could do came when Ensign Ralph Daniels Jr. of attack squadron VA-65 attempted to land his Douglas AD-4Q Skyraider during carrier qualifications. The LSO gave Daniels the wave-off signal and the inexperienced pilot evidently firewalled the throttle in an attempt to go around. The torque of the Skyraider’s big Wright R-3350 engine sent him over the side in a 90-degree bank and into the drink. Meanwhile, I was madly shooting with my Fairchild K-20 camera, and as Daniels plunged over the opposite side of the flight deck with his canopy open, I could hear him scream. I got up and ran across the deck and took three more photos of the airplane sinking while Daniels escaped from the Skyraider and was rescued by a Sikorsky HO3S helicopter.

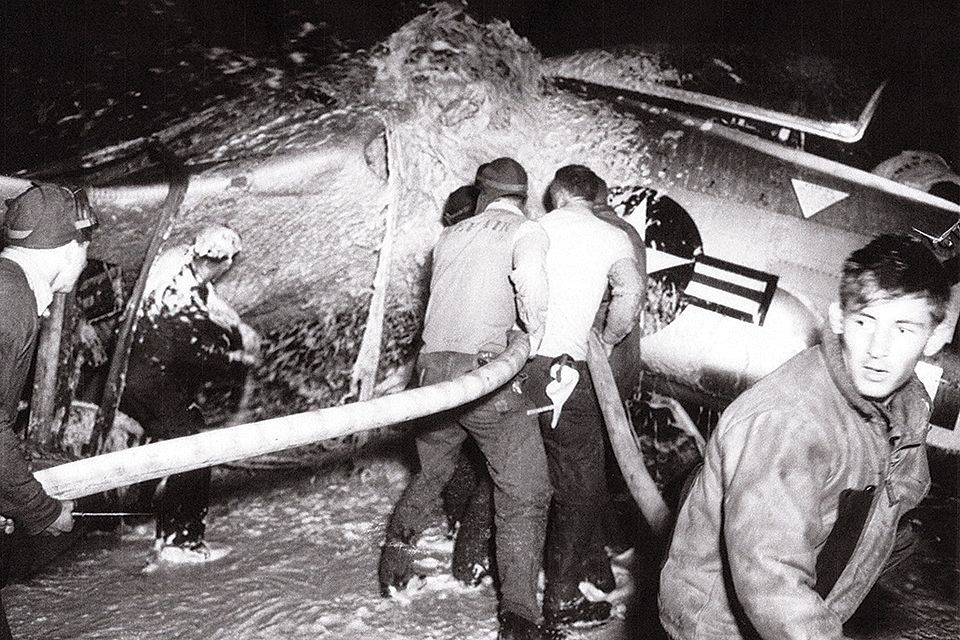

After Yorktown joined the Seventh Fleet off Korea, I captured one of the most dramatic images of my career during night operations by McDonnell F2H Banshees, in the process unwittingly endangering myself and the ship. Shortly after takeoff, one of the Banshees experienced engine problems and returned to the carrier. Just before the pilot touched down, one of the Banshee’s wingtips caught the flight deck and it cartwheeled into the nylon barriers, coming to rest against the rear of the island. The shock of it stunned me for a few seconds, and by the time I got to the destroyed jet the crash crew was hosing it down with fire foam and white-clad corpsmen were trying to extract the pilot. I took one shot with my 4×5 Anniversary Speed Graphic using a no. 22 flashbulb (as big as a 200-watt lightbulb) and was reversing the film holder when I heard a scream behind me.

“Don’t you dare take another picture!” came the commanding voice. The owner of that voice, 6-foot-4-inch Chief Boatswain Warrant Officer 4 G.A. Lentz, was the supreme commander of the flight deck and one of the most feared men on the carrier. I drew up my 5-foot-9, 140-pound frame, looked him in the eye and said, “Sir, it is my duty to take pictures.” What followed was a pronouncement reaching from aft on the flight deck all the way forward to the catapult launching crew, the likes of which I had never heard in my life: “If you take one more picture I personally will throw you over the side! The flashbulb might explode and ignite the jet fuel all over the deck!”

In my haste to get the shot, I hadn’t thought about the Banshee’s ruptured tanks leaking jet fuel onto the flight deck. The next day our chief warrant officer of the photo lab, B.C. Able, came into the lab smiling, winked and said, “I hear you had a few words with Chief Boats’n Lentz last night.” Nothing more was said, but that photo took up nearly a full page in the ship’s cruise book.

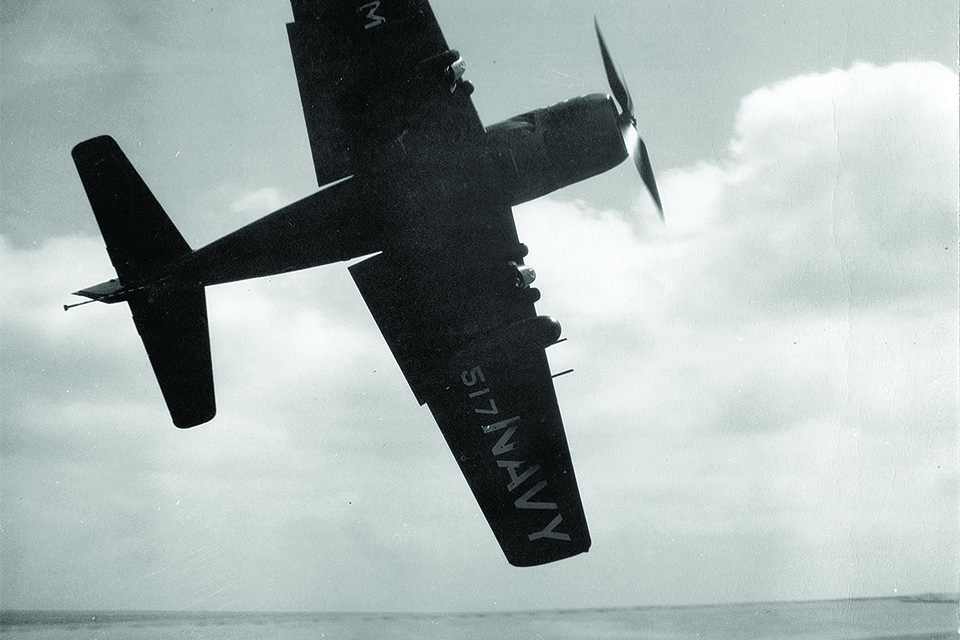

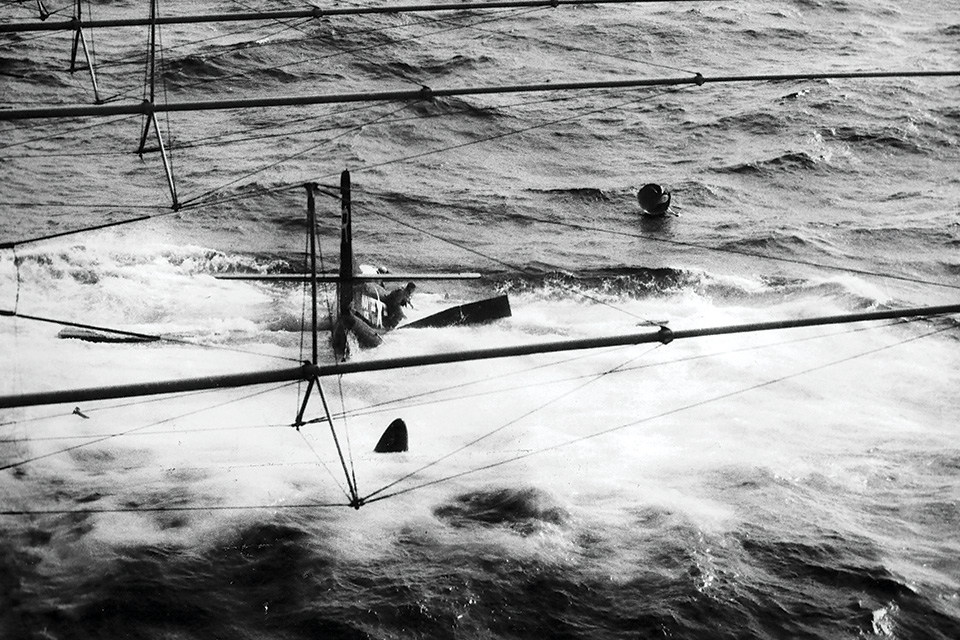

In August 1953, one month after the signing of the Korean War armistice, I witnessed another accident involving a Skyraider. As pilot Lieutenant Richard Arnicar and his two crewmen took off from Yorktown in a “Spad” equipped for anti-submarine search-and-destroy missions, it looked like a successful launch. Two seconds later, Arnicar’s throttle linkage failed and the engine quit. He banked the AD-4N to avoid being run over by the carrier and plunged into the Sea of Japan.

The crewmen quickly opened the side door and jumped into the sea, but Arnicar had suffered serious injuries. The lieutenant couldn’t move from the waist down, yet he had to get free of the airplane before it pulled him into the depths. He pushed himself up using both arms, attempting to get free of the cockpit, but his parachute straps held him back. Even after unlatching his parachute and equipment belts, he couldn’t extricate himself until an oncoming wave helped float him from the cockpit. As he floated free, Arnicar pulled the cord that inflated his bright yellow life vest and swam away from the sinking Skyraider.

A rescue helicopter soon arrived and the pilot expertly dropped a sling to Arnicar, hoisted him aboard and returned him to Yorktown. Diagnosed with a broken back, Arnicar was in need of immediate surgery. He was transferred to a tanker via a specially rigged stretcher and taken to a hospital in Japan.

We didn’t hear anything further about Arnicar after that, but years later his daughter contacted me. She said that after the accident Douglas Aircraft gave him a lifetime job as an engineer. He did it in a wheelchair.

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is a treacherous workplace. Many things can go wrong. Too many of them result in men dying.

Since my camera position usually was on the catwalk, on the after end of the flight deck across from the LSO, I could photograph incoming traffic, record landings and film crashes into the nylon barriers. After doing this for several weeks, I could tell if the landing would be successful or not just by the attitude of the incoming airplane. If it appeared to deviate from the ideal landing pattern, I would begin to take photographs or shoot motion picture film.

One day while we were retrieving Skyraiders off the West Coast everything seemed to be going well. As each Spad landed and stopped, two sailors, one from each side of the flight deck, ran over to the tail end of the plane and pulled the arresting cable from the tail hook using four-foot-long metal poles with a hook on the end. As the last of the large aircraft landed and caught the no. 3 wire, the steel arresting cable broke and snapped through the air like a whip. A deck hand was already running toward the tail hook, and the end of the cable struck him square in the chest, slamming him across the deck, over the catwalk and 90 feet down into the cold sea.

I was awestruck. It had all happened so fast and my reflexes were not quick enough to lift my camera. Immediately the ship’s whistles and bells sounded the “man overboard” signal. The destroyer behind us quickly responded with search procedures and our helicopter flew to where the man was last seen. Everyone aboard both ships strained their eyes to locate the sailor. We searched the sea for hours, but the man was never found. The medical officer said the cable strike probably killed him instantly—he was dead before he hit the water. I didn’t even know his name.

Another day I was in my usual location aft, shooting with a 16mm Kodak Cine Special. The motion picture camera had an optical viewfinder, which had the disadvantage of not permitting the cameraman to judge actual distances. Things appeared to be farther away than they actually were.

That day we were landing Grumman F9F Cougars, the latest Navy jet fighters. I was anxious to film some landings of the new aircraft, so I followed each plane through the viewfinder as it came in, running the camera when I thought something was unusual. As one of the Cougars was landing, the camera was on when the plane snagged the no. 1 cable. The aircraft stopped but a portion of the fuselage in front of the pilot broke off and hurtled down the deck. The heavy section with guns, radar and ammunition tumbled past and rolled in front of me as I looked through the viewfinder with the camera running. I filmed it as it bounced over the edge of the flight deck, hit the catwalk and dropped over the side.

After it disappeared I shut off the camera and looked around. I was surprised to see other sailors looking at me and shouting. One of the deckhands ran up to me and yelled, “Are you crazy? That piece of airplane almost took you over the side with it!” He showed me where the nose went over the side—the wooden flight deck had been gouged. It was barely 10 feet away from me. Looking through the viewfinder I hadn’t realized how close it was.

Yes, living on the edge of the flight deck can be very hazardous.

After my discharge from the Navy in May 1954, I enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1958 and spent three years as a recon squad leader. But that’s another story.

Richard G. Wells is the author of five self-published books, including Over the Side (from which this article is partially adapted) and Under a Helmet, Behind a Camera, available by emailing him at r.g.wells@comcast.net. Wells has received numerous awards for his photography and gained certification as a photo finishing engineer and photographic consultant.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue! To subscribe click here.