It wasn’t the first time that Harry Scovel had found himself in a Cuban jail. In the past, however, he’d been imprisoned by the Spanish for his unauthorized coverage of the Cuban insurrection. This time it was his own side—the U.S. Army—that had clapped him in the calaboose. He was there for violating a cardinal rule of reporting by making himself part of the story. In the eyes of the army, he was there for a far more serious offense. Pondering his possible fate, he might have envied the vermin whose cell he was sharing. Not only had he struck an officer, but the officer happened to be the commanding general.

Sylvester Henry Scovel had always been a rebel. Born in Pittsburgh in 1869 to Sylvester Finian Scovel, a Presbyterian minister, his middle name honored his maternal uncle, Henry Woodruff, who had evidently been a paragon of deportment. He’d so often heard “Why can’t you be more like your Uncle Henry?” from his mother that he never used his hated middle name in adulthood. For friends who may have considered “Sylvester” too stuffy, he answered to “Harry.”

When Scovel was 14, his father was named president of the University (now College) of Wooster, and the family moved to Ohio. Harry entered the school’s preparatory division but scotched his father’s dream that he might become the fourth in a line of Scovel ministers. Avowing atheism and declaring for a career in engineering, he enrolled in the University of Michigan but distinguished himself more in crusading against the fraternity system than excelling in his studies. He dropped out his sophomore year.

After a series of jobs around the United States that constituted a course of practical education, Scovel landed in Cleveland and achieved a measure of success as the general manager of the Cleveland Athletic Club. It’s possible that doors were open to him through a collateral branch of the family that included Philo Scovill, an entrepreneur, banker, and railroad director. Harry nonetheless made a name for himself by opening membership in the club to hitherto untapped social classes, including young Irish boxers from the working class. He even wrote the libretto to an operetta about early Cleveland that played to standing-room-only audiences for three nights.

Scovel also became a member of Troop A, an independent military company formed after the civil unrest surrounding the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Known variously as the First City Troop and the Black Horse Troop, it had become a unit of the Ohio National Guard. Its members hailed largely from the upper classes and drilled in military skills, especially horsemanship. Scovel must have fit right in, having equestrian skills previously learned at a Michigan military academy and possibly honed during stints at Western ranches. He also served as company bugler for two years.

Membership in a mounted drill team was expensive, as was moving in sporting circles. Despite a good salary and free room at the Cleveland Athletic Club, Scovel found himself in serious debt. Back in Wooster, his father offered to settle his debts if he agreed to take a job with an insurance company in Pittsburgh. Harry went to Pittsburgh but was saved from an insurance career by fate. Early that year a full-fledged insurrection had broken out in Cuba, and Harry went to a rally in support of the Cubans. Scovel became an instant convert—the rebel had found his cause.

Stories about Cuban resistance to Spanish oppression had begun dominating the front pages of American newspapers in the embryonic days of “yellow journalism”—the sensationalistic, scaremongering style of newspapering designed to drive up circulation at the expense of truth. Scovel was seized with the desire to help tell that story and arranged to send copy to several Western newspapers as well as to the New York Herald. With the instinct of a born reporter, he grasped the importance of getting to the sources of the news. Bypassing Key West and Havana, sources of most insurrection stories, Scovel hopped a steamer to Cienfuegos on the island’s southern coast. From there, with the aid of friendly Cubans, he made his way to the camp of Máximo Gómez.

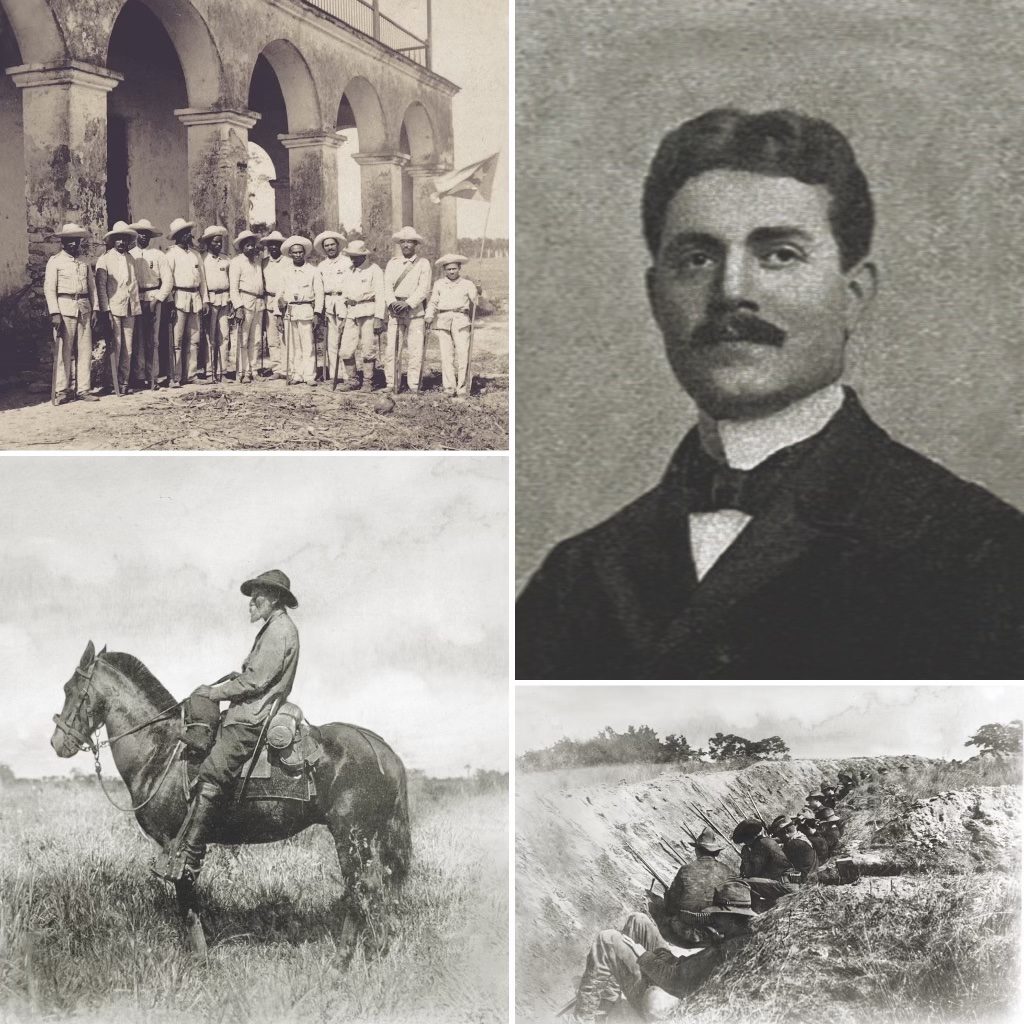

Gómez was one of the insurgency’s three top leaders, the others being Antonio Maceo and Calixto García. Elbert Hubbard, a famous American writer, would make one of them a household name with a story titled “A Message to García,” in which he related how President William McKinley dispatched “a fellow by the name of Rowan,” who secretly landed in Cuba, “disappeared into the jungle, and…traversed a hostile country on foot” to deliver McKinley’s letter to the Cuban commander. It takes nothing away from Rowan to observe that for three years before his mission, a few newspaper correspondents had routinely been making their way to the rebel camps and getting out their stories.

“They are taking chances that no war correspondents ever took in any war in any part of the world,” wrote Richard Harding Davis. “For this is not a war—it is a state of lawless butchery, and the rights of correspondents…and of noncombatants are not recognized.” Among the chances they ran, he said, were “being put in prison and left to die of fever.” Davis himself was an established writer of descriptive reportage and short fiction rather than a war correspondent. Sent by William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal early in 1897 to send back stories on “the Horrors of the Cuban War,” he never reached the actual field, settling instead for “a car window view of things.”

Most reporters in Cuba were confined to Havana and the railroads and subject to military censorship. General Aresenio Martínez Campos, the Spanish commander, had constructed a line of fortifications along the principal railroad line, bisecting the island across its narrow waist. Underbrush and jungle were cleared on both sides of the tracks, which were guarded by barbed wire barricades and blockhouses. It wasn’t entirely impenetrable; rebels occasionally crossed in force. A handful of reporters also moved freely across the line, notably George Rea of the New York Herald, Grover Flint of the Journal, and Scovel.

The journalists who managed to reach the interior provided antidotes for some of the fantasy accounts coming out of Havana and Key West. Havana was never under siege; “battles” were more often skirmishes or sorties. This was classic guerrilla warfare, as Gómez and his peers had no intention of trying to capture Havana or engage superior Spanish forces in open battle. Their strategy consisted of bringing the Spanish to heel by burning the sugarcane fields and ruining the Cuban economy.

Getting stories of this irregular warfare to their newspapers could be as difficult for reporters as reaching the scenes of the action. To avoid having their copy eviscerated by the Spanish censors, reporters had to smuggle their stories out. Some papers sent boats to the Cuban coast at arranged times and places to receive dispatches from their correspondents. Some reporters hired couriers to carry their reports to the coast. Scovel and Rea were valued not only for their reportage but for their ability to get their stories to their papers.

Scovel returned to the United States at the end of 1895, partly to recover from an infected wound and partly to report in person to a new employer: Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, formidable rival of Hearst’s Journal. Change of a more portentous nature was taking place in Cuba, where Spain replaced General Campos with General Valeriano Weyler, known to history by the epithet “Butcher Weyler.” The new commander in chief had little love for “meddlesome scribblers” and barred journalists from accompanying either the Spanish or the insurgent forces.

When Scovel returned to Cuba early in 1896, he went with the mission of ascertaining whether the stories of Spanish atrocities that had been coming out of the island were true. Ignoring Weyler’s fiat, he traveled with Maceo’s forces in Havana Province. In one of journalism’s earliest instances of investigative reporting, he began documenting deeds against noncombatants by Spanish forces that would later be considered war crimes.

Maintaining that he went with a certain amount of skepticism, Scovel uncovered examples of barbarity “so beastly, so indecent no Apache could have conceived anything equal to it.” His reports began appearing in the World in May, including a gruesome description of mutilated Cuban corpses:

The skulls of all were split to pieces down to the eyes. Some of these were gouged out. All the bodies had been stabbed by sword bayonets and hacked by sabers until I could not count the cuts; they were indistinguishable. The bodies had almost lost semblance of human form….Fingers and toes were missing….The Spanish soldiers habitually cut off the ears of the Cuban dead and retain them as trophies.

Scovel catalogued 212 cases of Spanish brutality, backed up by 196 affidavits. His dispatches continued through June. “Extermination of the Cuban people under the cloak of civilized warfare is Spain’s settled purpose,” he wrote. The World praised its man in Cuba as having “all the great and high qualities of the war correspondent—devotion to duty, accuracy, graphic descriptive power, absolute courage and skill.”

After a sojourn in New York, Scovel was back in Cuba early in 1897, in defiance of a $5,000 reward that Weyler had offered for his capture. Though he was probably traveling incognito, his luck soon ran out. Fitzhugh Lee, the U.S. consul general in Havana, reported that Scovel had been arrested on February 5 as he was trying to send out dispatches on the southern coast. He was held on a laundry list of charges, including crossing Spanish lines and communicating with the enemy. Some were capital offenses.

Scovel’s capture proved to be less problematic for the prisoner than for Spain, which was eager to avoid inflaming anti-Spanish sentiment in America. Sent to a prison in Sancti Spiritus, in the middle of the island, Scovel found his accommodations a far cry from death row. Cuban sympathizers flooded his cell with flowers and food. “Señor Sylvester” had become a folk hero to many for his exploits in getting their story out to the world. He even managed to send stories to the World from his cell, datelined “Calaboose No. 1, Prison of Sancti-Spiritus.”

Pulitzer’s newspaper promptly took up the cause of its imprisoned reporter, which it presented as a matter of national honor. Illustrating its story of his arrest was a four-column drawing of Scovel on horseback, a military-style mustache over smoothly shaven jaws and chin, his eyes shaded by a rakish, wide-brimmed hat.

Dozens of American newspapers joined the crusade to spring Scovel. Fourteen state legislatures and the U.S. Congress passed resolutions urging the State Department to take action. Many stressed his status as a noncombatant, with the World observing that the nearest thing to a weapon he carried was “a typewriting machine.” Spain’s ambassador in Washington informed Madrid that any injury to Scovel might fatally turn public opinion in America against Spain. Madrid in turn instructed a reluctant Weyler to release his prisoner.

Scovel returned to the United States a conquering hero. He met President McKinley in the White House shortly thereafter. Days later he married Frances Cabanné, a Saint Louis socialite he had met the previous fall. The World sent its new star reporter to the Balkans to cover the Greco-Turkish War, but the war was essentially over before Scovel arrived. He went to Alaska to cover the Klondike gold rush, but the World soon summoned him back for reassignment.

Spain had recalled Weyler, clearing the way for Scovel’s return to Cuba. Taking Frances with him, Scovel submitted to the formality of an arrest on the old charges and release under parole. He was permitted to resume work as a correspondent, and Ramón Blanco, the new Spanish commander, even allowed him to cross Spanish lines to visit Gómez’s camp. He was accompanied by the U.S. consul at Sancti Spiritus, who was carrying Spain’s formal offer of local autonomy for Cuba, to be guaranteed by the United States.

As reported in the World, Gómez replied that Spain’s offer was too late. Scovel returned to Havana, where anti-American riots by the pro-Spanish faction broke out in January 1898. Secretary of the Navy John D. Long ordered the USS Maine to Havana harbor. Ostensibly it was a goodwill gesture; implicitly the battleship put Spain on notice

that the U.S. government stood ready, if necessary, to protect American lives and property.

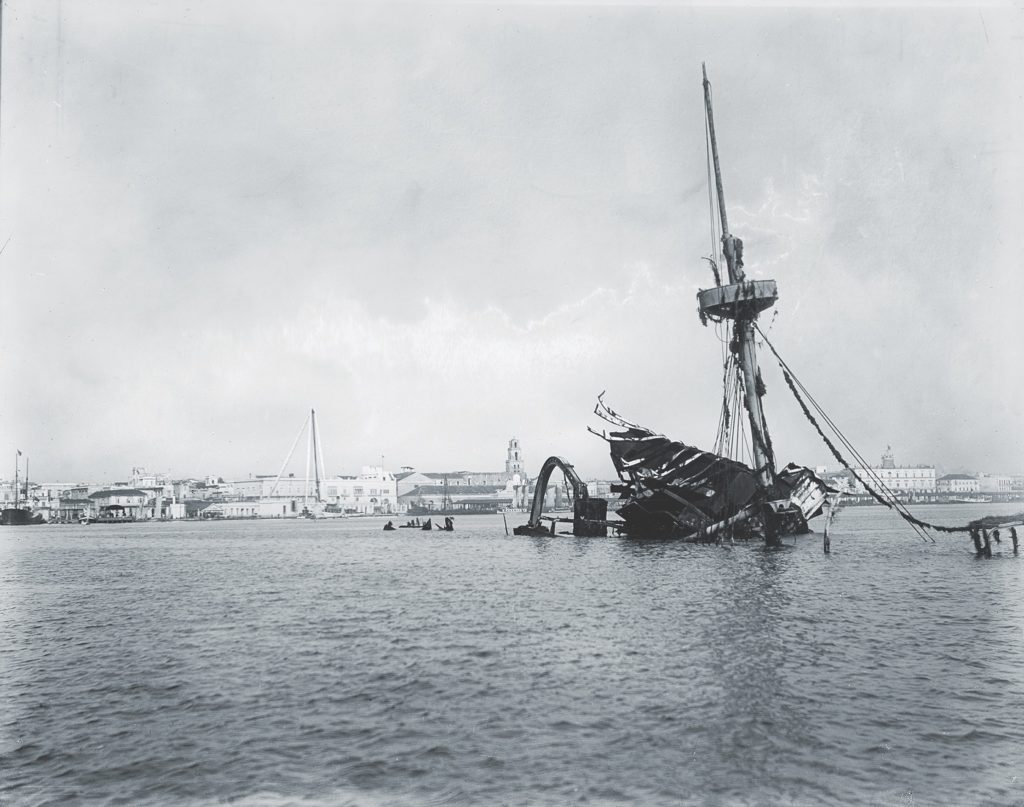

At 9:40 p.m. on February 15, 1898, Harry and Frances Scovel were dining near Havana’s Central Park with George Rea of the Herald when a terrific explosion rattled dishes and shattered most of the windows in the neighborhood. It came from the harbor, brightly illuminated against the moonless sky. After seeing Mrs. Scovel to safety, the two reporters raced to the scene of the explosion and bluffed their way through a police cordon by claiming to be officers from the blazing Maine. Havana’s police chief waved them into his boat, which set off toward the ship through exploding small-arms ammunition overhead and bodies and debris in the water.

There was little left to see, other than that most of the damage had occurred in the forward end of the ship. Captain Charles Sigsbee ordered survivors to abandon what was left of the Maine as it settled slowly to the bottom of the harbor. Scovel and Rea returned to the Havana telegraph office, where only three messages were allowed to go out that night. First was Sigsbee’s terse message to the Navy Department, then a hundred-word dispatch to the Associated Press. The only exclusive report was Scovel’s dispatch to the World, written on a blank, prestamped cable form he had surreptitiously lifted from the censor’s desk that very morning. The most provocative of its five sentences stated: “There is some doubt as to whether the explosion took place ON the Maine.”

That question would inspire screaming headlines in the yellow press for the next several weeks. If the explosion had taken place on the ship, the implication was that it was likely accidental in origin. If it had not taken place on the ship, the cause was assumed to be a torpedo or a mine, presumably of Spanish origin. (Generally ignored was the observation that Spain had less to gain from the Maine’s sinking than did the insurgents.)

Scovel, on behalf of the World, tried to arrange for divers to examine the wreckage, but the Spanish squelched that idea. Instead, a U.S. naval court of inquiry came to Havana to make an official report. Spain, with Captain Sigsbee’s approbation, tried to keep American correspondents away from the investigation, but Scovel continued to visit the site without permission. “The ubiquitous American newspaper correspondent could not be denied,” Sigsbee wryly commented.

By the end of March the court of inquiry had issued its finding that the cause of the Maine’s destruction had been a submarine mine of indeterminate origin. It may not have been the chief casus belli, but it stirred up more war fever than the cause of the Cubans ever had. The last of the American reporters left Havana with Consul General Lee on April 10—the eve of McKinley’s war message to Congress.

Key West and Tampa became the mobilization points for the Atlantic Fleet, the Fifth Army Corps, and the war correspondents who would cover their campaigns. The reporters included old Cuba hands like Scovel and a couple hundred newcomers to the theater of war. “Amid the surging excitement of Key West, no figure moved with calmer assurance than the great Sylvester Scovel,” observed Ralph Paine, of the Philadelphia Press. “To be ignorant of Sylvester Scovel was to argue yourself unknown….Through the daily journalism of his time this energetic young man whizzed like a detonating meteor.”

Some representatives of the fourth estate were even more celebrated than Scovel, notably literary stars such as Richard Harding Davis and Stephen Crane. Davis returned to Cuba for the Journal, Crane would write for the World—two giants of letters facing off for the two giants of yellow journalism. Regular reporters, perhaps, were less impressed. The newspapers assigned veteran correspondents to both of the stars, Christopher Michaelson to Davis and Scovel to Crane—not to help with their writing, but simply to get them to the news and to get their copy while it was still news. Scovel was put in general charge of the World’s team, telling Paine that he might travel on the paper’s dispatch boat, the Triton, in return for sharing his copy with the World.

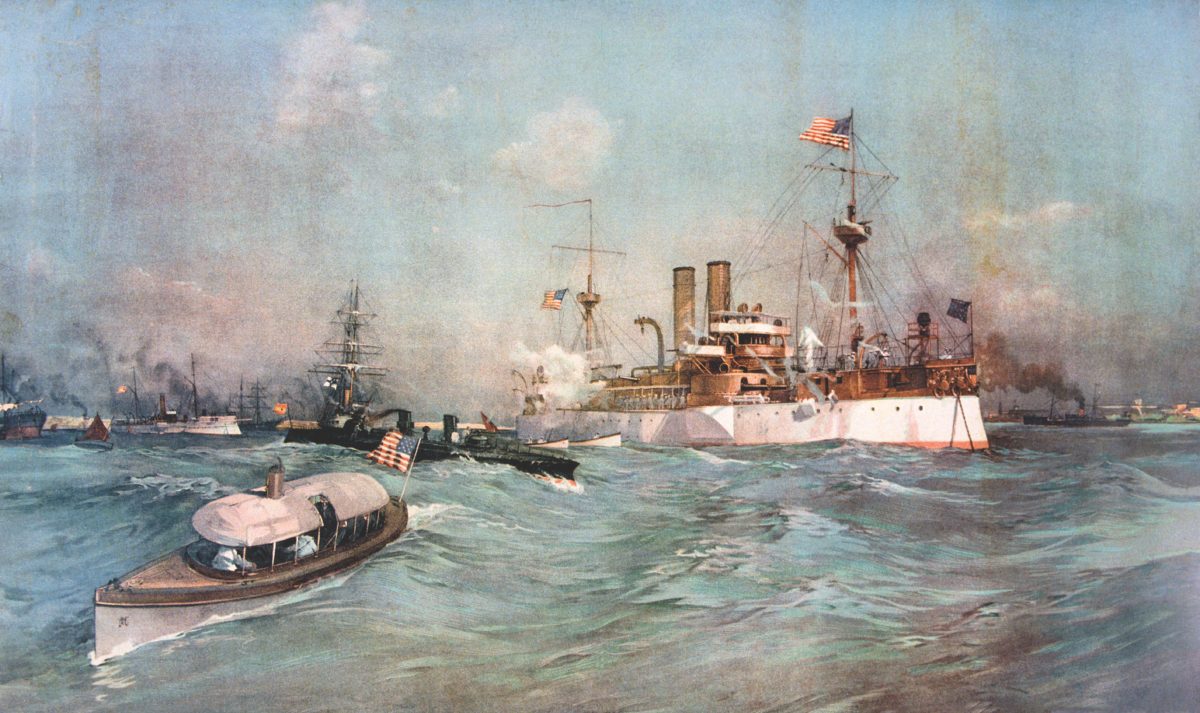

When Rear Admiral William Sampson was ordered to blockade Havana with the Atlantic Fleet, the correspondents followed in a variety of chartered craft. In need of detailed information, Sampson could think of no better source than Scovel. Putting the Triton at the service of the U.S. Navy, Scovel sent reporters and a photographer ashore to obtain intelligence and pictures of Havana’s defenses. He sent messengers to make contact with Gómez, inform him of America’s declaration of war, and discuss ideas for joint operations. Paine later complained of searching in vain for the Triton to take his dispatch because Scovel had commandeered it “to take soundings for the Admiral.” Paine’s feelings toward Scovel oscillated between hero worship and resentment. “Much as I admired Sylvester Scovel the magnificent,” he said, “it was to wish that he might have attended more strictly to the newspaper game and left the management of the war to Admiral Sampson.”

Scovel didn’t always take the Triton. When Spanish forces captured two of his agents, he boarded the navy tug Uncas to help negotiate for their release. This proved to be a violation of navy regulations, leading Scovel to be officially barred from all naval vessels and stations. Sampson wrote to Secretary Long, explaining the mitigating circumstances behind Scovel’s offense. “Mr. Scovel,” he wrote, “has done such exceedingly good work among the insurgents, and given us so much valuable information at very great risk to himself, that I should feel obliged if you would enable me to act at my discretion in the matter.” Scovel appealed to both Long and McKinley to have the ban lifted, but in the meantime he simply ignored it. He hopped aboard the armed tug Tecumseh to help land two Cuban couriers on the coast, coming under fire himself in the process.

In June, however, action in the Caribbean dramatically shifted from northwest Cuba to the extreme southeastern coast. Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete had left the Cape Verde Islands with a Spanish fleet and disappeared into the Atlantic. Guesses as to his destination ranged from the West Indies to population centers along the eastern coast of the United States. New York’s World and Herald jointly sent a dispatch boat on a complete 1,500-mile circumnavigation of Cuba that turned up, Scovel wrote, “no Spanish warships in the harbor or on the high seas.” Soon a report came in that Cervera had found a harbor in Santiago, and Sampson’s fleet and its newspaper satellites weighed anchors for the other end of Cuba.

Sampson proceeded to bottle up Cervera in Santiago Bay while awaiting the arrival of Major General William Rufus Shafter and the Fifth Army Corps, which would have to take the city of Santiago before Sampson could enter the harbor. Meanwhile, Sampson was in need of intelligence on this new theater of operations, and one of his primary sources again proved to be Scovel. Taking Crane with him, Scovel landed in rebel territory west of Santiago and passed through Spanish lines. After climbing a 2,000-foot mountain, they were rewarded with a bird’s-eye view of Santiago Bay, which Scovel later described in the World:

There upon the bosom of the green-fringed harbor lay Cervera’s once dreaded squadron. There were the four big warships, easily recognized—the Cristobal Colon, Vizcaya, Almirante Oquendo, Infanta Maria Teresa, and the old Reina Mercedes…I climbed a tree and made a rough sketch of the scene before me, so that a working map could be made from it, and to fix the location of all important points firmly in my memory.

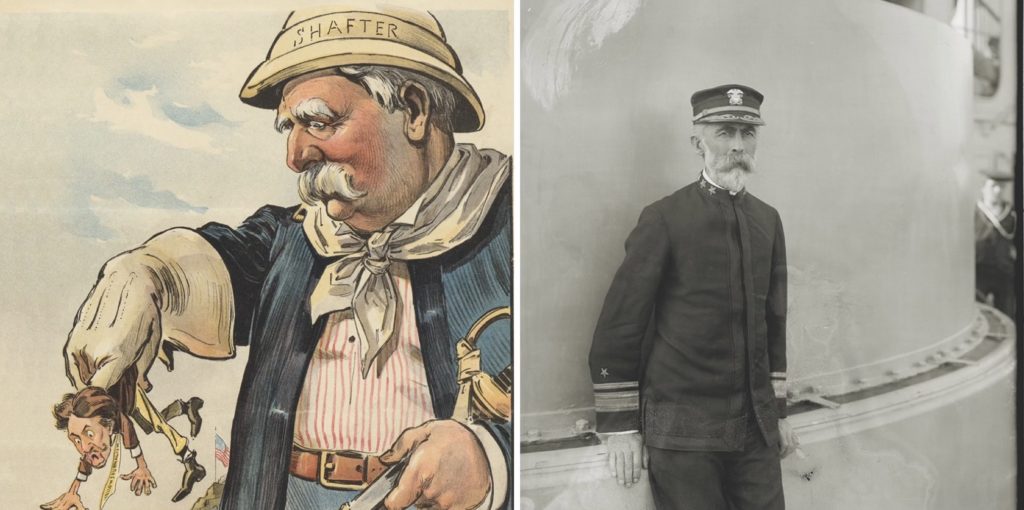

It was easy to see why Sampson was willing to overlook regulations in favor of reporters; Shafter proved to be a different story. A Medal of Honor recipient for his actions in the Civil War, Shafter now cut quite a different figure. At 300 pounds he could no longer mount a horse. Colonel Theodore Roosevelt of the volunteer “Rough Riders” regiment bore him no respect, writing his friend Henry Cabot Lodge that the commanding general was “criminally incompetent” and guilty of gross mismanagement. Reporters were equally disrespectful, and with reason. Shafter’s aide de camp had called them a nuisance and threatened to expel them from the expeditionary force. When the redoubtable Davis tried to tell the general what kind of writing he did, Shafter rudely cut him off. “I do not give a damn what you are,” he told Davis. “I’ll treat you all alike.”

By the end of June the Fifth Corps was in position east of Santiago. Reporters hadn’t been expelled from its lines, but in the face of shortages for the troops, the commissary frequently denied their efforts to purchase rations. On the eve of the climactic battle Scovel organized the World’s coverage and set up a camp with refreshments on the height of El Pozo just behind the lines. During the battle he followed the troops to Kettle and San Juan Hills, writing his dispatch under a tree and warning other correspondents to avoid an area covered by Spanish sharpshooters. A messenger carried his story on horseback to the World’s base, announcing that Americans had carried the day and cleared the way to the very gates of Santiago.

For two weeks the Fifth Corps stood before those gates, until Shafter had negotiated the surrender of not only the city’s garrison but all Spanish forces in the district. He arranged for a formal transfer of power on Sunday, July 17, and let it be known that correspondents were not invited. Some of the more enterprising ones managed to slip into the city anyway.

In the plaza fronting the governor’s palace, an American regiment and its band stood at attention to witness the raising of the Stars and Stripes atop the palace. Ralph Paine described the bit of improvisational theater that followed. As three officers bearing the colors approached the flagpole, suddenly “there appeared the active, compact figure of Sylvester Scovel, Special Commissioner of the ‘New York World.’ ” What might have been seen as an unwarranted intrusion seemed to Paine a matter of course. “At this particular moment in the histories of Spain and the United States, what was more natural and to be accepted than that Scovel should be in the center of the stage?”

Shafter didn’t see it that way. Livid, he bellowed, “Throw him off!” As several soldiers moved to carry out the order, Scovel beat a tactical retreat from the roof. He rushed into the square to confront Shafter. Words were exchanged; then more than words.

“He [Shafter] told Sylvester Scovel to shut up or be locked up, and brushed him to one side,” Paine wrote. “Sylvester Scovel swung his good right arm and attempted to knock the head off the major-general commanding the American Army in Cuba.” Shafter ordered the reporter arrested, and Scovel was summarily hauled off to what was described as “a moss-covered calaboose” while the surrender ceremony proceeded.

Scovel had been “abusive and insubordinate,” Shafter reported to the War Department, “one word leading to another, until he struck at me, but didn’t hit me. I could have tried him and had him shot…but I preferred to fire him from the island.” As Paine told it, Scovel’s swing wasn’t a complete miss: “It was a flurried blow, without much science behind it, and Scovel’s fist glanced off the general’s double chin, but it left a mark there, a red scratch visible for some days.”

“Never again do I want to pass a night in this hellhole with all these creeping things,” avowed a somewhat chastened Scovel on his release the morning after his incarceration. He realized, said a fellow reporter, that “he would be shot in any country with a military system.” No doubt Shafter on his part would have had second thoughts about executing a reputed acquaintance of President McKinley. Scovel later got to tell his side of the story, claiming that he had approached Shafter to apologize for disrupting his ceremony. “You son of a bitch,” he quoted Shafter as replying, “you and all your tribe are goddamned nuisances.” Scovel took exception to the general’s language, Shafter hit him, and he returned the blow.

Reaction to the contretemps initially ran against Scovel. He was banned from all U.S. Army and Navy bases; even the World decided it could dispense with his services. Before long, however, even the fastidious Davis said that he had left Santiago for fear that he’d “do what Scovel did.” The World reconsidered and invited Scovel to write his own account of the affair for the paper. He appealed personally to McKinley to rescind his banishment from accompanying U.S. military forces, which the president did by the end of 1898.

Scovel turned down the World’s offer of a European correspondent position in favor of returning to Cuba. He covered the early days of the American occupation until the subject faded in public interest. His war reporting days were over after one war, but in what has been dubbed “The Correspondents’ War,” he had been the undisputed leader of the pack. “From the perspective of editors and reporters in the field,” noted media historian Mary S. Mander, “Sylvester Scovel—rather than literary star Davis or his New York World counterpart Stephen Crane—was the beau ideal.”

Scovel became a consulting engineer for the U.S. occupation government before engaging in a number of business ventures, including one of Cuba’s first automobile dealerships. But his life was cut short at age 35 from complications that followed an operation in a Havana hospital to remove an abscess of the liver.

Frances brought Scovel’s remains to Wooster for burial. Troop A sent a mass of roses that covered the casket. Members of the Ohio National Guard who had seen duty in Cuba served as pallbearers, fired a volley in salute, and sounded taps. The family raised a tombstone bearing the name Scovel, under which was carved Sylvester Henry, 1869–1905.

Uncle Henry appears to have had the last word.