National Archives |

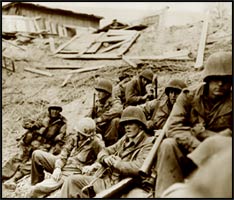

| With their objective clearly visible, troops from the 89th huddle around their assault boats and wait for the final order to advance. |

A little past 2 a.m. on March 26, 1945, a scant 42 days before the war’s end in Europe, about 250 young men out of a force of nearly 420 were casualties in an assault as unthinking and unnecessary, but also as brave, as the Charge of the Light Brigade, immortalized in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s famous poem. This action, however, was hidden away by Third Army headquarters, and as a result the night was lost to history.

For many years after that tragically fateful night I had no time to remember it, or more accurately, I tried very hard to forget it. My life was geared toward the future–going to college, raising a family, establishing a successful career and retiring.

A character in Les Miserables, lamenting the death of his comrades on the 19th-century Paris barricades while he lived, triggered a flood of memories in me when I saw the show, and it all came rushing back. I had not really forgotten that night, and now think of it every day. This is the story of that evening, an incident too often overlooked by many of those writers and researchers who have chronicled the exploits of the Third Army.

I was a member of C Company, 168th Combat Engineers, a bastard unit assigned to the Third Army. Our mission was to keep the roads open and passable for men, tanks, trucks, artillery and anything else that moved. We plowed snow-covered roads, built bridges over streams and rivers, made corduroy roads from forests we cut down when the mud got too deep for trucks and tanks, lifted mines, planted mines, assaulted fortified positions with explosives and established bridgeheads with the infantry so that larger bridges could be built to ferry the tanks and artillery across.

One day at winter’s end, when we reached our bivouac area, our sergeant said the squad would meet later that evening for a briefing. In my almost two years in the Army I had never been part of a briefing. Since we arrived on the Continent, our entire world had consisted of only what we could see with our own eyes. This confined our view to a very small area–the world of our 12-man squad and the ground covered by our truck.

We did know we were winning the war because we were always moving east. We did not know where we were, except that road and village signs changed from French to German, so we figured we were in Germany. But where? We did not know who was to our north, or south or west; it had to be the Germans to the east. We knew only what we saw.

The briefing gave us some information and greatly expanded our world. We learned that this was Saturday, March 24, that we were to lead an assault across the Rhine River carrying troops of the 89th Infantry Division, and that this crossing was scheduled for Monday, March 26, at 2 a.m. at a place called St. Goar. We were told that the attack would be made in manually rowed M1 assault boats, each carrying three engineers and a 12-man infantry squad. Our 12-man engineer squad would divide into four boats with an entire infantry platoon, plus medics, noncoms and officers. We believed that so far in this war, nobody had yet crossed the Rhine and we would make the initial historic assault. We had not the slightest inkling that the river had already been crossed successfully three weeks earlier at Remagen, and at many other spots since. Tens of thousands of Allied soldiers were already across to our north.

National Archives |

| GIs offload flimsy plywood assault boats from the 168th’s trucks prior to the attack. Each assault boat was supposed to carry three engineers who were charged with handling the craft and seeing that the infantry squad it carried was delivered to the shore across the Rhine River. |

We were instructed to self-select our groups of three, and we soon divided up based on close friendships. There was to be one engineer in each front corner of the rectangular boat, with the third in the center rear, using his paddle as a tiller. The infantrymen were to file in behind us in three rows of four each. The two outside rows were to paddle along with the engineers who were to set the pace.

Once my group of three had gotten together, we decided among ourselves that before we got into the boats we would untie our boots so that they could be easily kicked off. We would also drop our gas masks and heavy cartridge belts so that we would not be burdened with this extra weight in case we capsized. Our job that night was to deposit the infantrymen on the east bank of the Rhine, row back to the west bank and find our way back to our units. Our task would then be done, since another engineer battalion was to build a bridge across the secured banks. After that, we would head to our sleeping areas for a fitful night’s rest.

The next day was an ordinary one for us. A previous day’s reconnaissance patrol had found a tar burner and stacks of solid tar. The squad was up at dawn and went to patch a road that wound up a hill. We all guessed the Rhine was on the other side, but we didn’t know where we really were. We fired up the burner and melted the tar, which we then dribbled over cracks in the road. Not a single vehicle of any kind passed us as we worked until midafternoon. We were up ahead of the armor and even some of the infantry. We talked about the coming events throughout the day, wondering when this assignment would end.

At 9 p.m. we assembled for the trip to St. Goar. During the several hours before we left, some of us wrote letters, some cleaned rifles, some napped. The official history of the 89th Infantry Division said that ‘Sunday, March 25th, was a day of prayer…H-hour the culmination of nearly three years of preparation was at hand.’ It might have been for the infantry, but it certainly wasn’t for the 168th Engineers. My squad had put in a trying day’s work tarring a piece of an apparently little-used road, and there wasn’t any prayer, organized, official or otherwise. We were all buzzing about that night, however.

The official record also says that ‘for hours the [89th] Division’s 105’s and 155’s had been pounding known and suspected targets on the far side, but now the barrage was stilled and an uneasy quiet settled over the gorge.’ This is not what I recall. I remember sporadic shells at what seemed like random intervals, occasionally over our heads and impacting on the far side of the river. Of course that’s what we could see and hear. For all we knew about strategy and tactics, it could have been a pounding. In fact, we were led to believe the attack was to be a surprise with no air cover. There was no air cover, but it was not a surprise.

We mounted our trucks at the appointed hour. There was total blackout that night, but the moon was bright and visibility good. In short order we began to pass the infantry. They were lined up — huddled might be a better description — on both sides of the road. They were in full combat gear, solitary figures stretching in both directions, as our blacked-out truck and the others of our company passed silently by. There were no words of encouragement from either side, only curiosity and questioning stares. We all knew what was coming up. A second D-Day, we thought.

The trucks pulled trailers carrying pontoons, Treadway bridges and the assault boats. They crept bumper to bumper down the narrow road. My truck pulled a trailer of 12 assault boats, enough for our platoon. We halted on the side of the street behind a long line of other trucks. There were many more lining the curb behind us.

The houses alongside my truck were two and three stories high, with steps leading to the front door. As we got out of the truck, we were told to hang around the immediate vicinity. My two friends and I, who were to man one boat, sat down on the steps.

After several minutes of nothing happening, we all walked down to a corner, about 50 yards away. There was a break between the attached houses, an entry to a beach that ran down to the water, which clearly reflected a full moon. The river was very wide and moving rapidly northward as fast as I’ve ever seen a river flow. Otherwise, the view was peaceful and quiet and not at all ominous. It made us feel optimistic about what was to happen, perhaps no opposition at all — an unhindered crossing. We returned to the steps next to our truck, and bantered in the usual GI time-filling way.

Sometime after that, while chatting on the steps, we heard the whoosh of several shells coming in. These rounds were to our north, but one hit the building on the corner facing the beach, where we had just looked at the river. The shelling stopped as suddenly as it had started. After a few moments of silence, we moved down to the beach entrance so the three of us could see what was going on. We saw the chips in the building where the shell had hit.

National Archives |

| GIs wait to board the assault boats. |

Not fully realizing the implications of what had happened, we went back to our roost on the steps and resumed talking, now about the shelling. We didn’t think to take cover or get off the street while we waited for H-hour. We hadn’t realized that these first few rounds were range-finding, zeroing in, so they could drop ensuing shells between the buildings lining each side of the street, and directly on the trucks carrying all the assault and bridge-building equipment.

After another short bout of gabbing, we heard the whoosh of a closer shell, much louder and heading directly at us. We barely had time to flatten out on the steps. The shell landed between the three of us and our truck. The impact jolted me, and the strong smell of burnt gunpowder surrounded us. I felt nothing anywhere on my body and knew I was not hurt. After a few moments of recovery time, with my ears still ringing, and assuming my buddies were also OK, I yelled, ‘Let’s get the hell out of here and find some cover!’ I took off down the street. I ran into a building through large open doors. The space seemed cavernous and was totally black. After my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I saw there were many other helmeted figures lying prone all over the floor. Others came running in, but not my two friends. I never saw them again, although I heard that both survived, one badly wounded. The shelling continued for what seemed a lifetime, killing or wounding a dozen engineers.

After some time lying there, while shells landed outside, someone dashed in saying that everyone from the first squad of the first platoon of C Company should move directly across the street, enter a courtyard and go through the first door on the right where the squad was assembling. Encouraged by the messengers braving the shellfire, and despite my fears, I zig-zagged to the assembly point.

Only nine men showed up; my two close friends and a third were missing. The preplanned trios had to be rearranged; I was to be teamed with our corporal from Chicago and a fellow New Yorker. We decided that the corporal would man the paddle tiller. The New Yorker and I would take the front spots, he on the left and me on the right. We were told a reconnaissance boat had already entered the river and had gotten across unfired upon. (It turned out that due to heavy fire, they had turned back, but because of the rapid current, landed far downstream, out of radio range.) It was getting on to H-hour, 2 a.m., and we moved out to our truck trailer where the boats were stacked. They had not been damaged. The barrage of shells had stopped by this time.

Squad by squad, the infantry came down the steep hill onto the street. Each stopped at our stack of boats and lifted the uppermost one down to grasping hands. The trailer was emptied in minutes. The men then carried the boats through the passageway to the beach and to the edge of the water.

National Archives |

| Tense GIs from the 89th Infantry Division crouch low in an assault boat during the division’s crossing of the Rhine River at Oberwesel, Germany, on March 26, 1945. |

An infantry lieutenant came down the beach and told us to get the boats into the water; it was nearly time. As soon as the boats were in the river, men from the 2nd Battalion, 354th Infantry Regiment, piled in helter-skelter. My spot was taken, but in the chaos we couldn’t get the passengers reorganized. I took a middle spot on the right side, two positions removed from where I should have been, a lucky break as it turned out. As we waited to shove off, I dropped my equipment and rifle to the bottom of the boat, right under me. My boots were unlaced and helmet straps loose. We were wearing winter clothes and combat jackets. The infantrymen were wearing light field packs but carried heavy equipment, including bandoliers and full canteens. I can’t recall the launch signal, but when the lieutenant in the middle of the boat said, ‘Let’s go,’ we took off. Boats to our left and right moved out simultaneously, silently and smoothly.

The moon was bright, and the gorge between the cliffs seemed eerily lit. The water was racing extraordinarily fast downstream. We were about halfway across, paddling very hard because of the swiftness of the current, when we first saw the tracers. They illuminated the night, these lines of light coming from multiple sources on the far bank. The sight was fearful and breathtaking, almost magical in nature. The Germans were using a high ratio of tracers because the streams of light were continuous. They were firing 20mm high-velocity anti-aircraft guns in level trajectory against us.One line of light was off to our left, downstream, and the strong current was moving our boat directly into it. We all saw it. Everyone was shouting — some to head back, others to move the boat to the right against the current. We yelled for the men on the right to stop rowing so those on the left could turn us to the right.

It could not be done. The river was much too powerful. Trying as hard as we could, utilizing all our strength, we could not alter the downstream course, and, in one explosive burst, the lit-up line of fire tore into and overwhelmed the 16 in our boat. We felt it literally tear into us.

Of the soldiers who we were taking across, the division reported that only 11 men of Company E’s 2nd Platoon got ashore. Three of Company F’s four 1st Platoon boats were sunk. All the paddles of the 3rd Platoon, E Company, boat were shot away, and the craft circled crazily and drifted downstream, reaching shore with its wounded an hour and 20 minutes later. The division reported that’smoke formed a pall over the river and the screams of the dying and wounded rose over the angry crackling of the flames,’ and that ‘a storm of German shells churned the water.’

The infantry commander reported: ‘Few of the original boats had made it across. Some were blown up or sunk….Others drifted downstream under merciless fire without paddles.’ The engineer commander reported that ‘eight boats landed at the far shore. The fate of the balance will…never be correctly known’ and that at ‘8 a.m., when it was relieved, Company C consisted of six men, three wounded.’

Seconds after the explosive force ripped into us, an unworldly silence covered the boat. The firing continued, along with the deadly lightstreams. We barely heard the noise — it came from a distant world. Our world had shrunk once again to the few still left aboard this small boat. Others had been blown over the sides by the force of the 20mm fire.

I found myself amid an unmoving tangle of arms, legs and bodies in the bottom of the boat. I was not sure what had happened. There was a strange sensation throughout my entire body that my mind could not grasp. My left leg seemed to be missing; I could not feel it. There was no pain, just a light-headedness that was completely new to me. I had never experienced such a feeling. It wasn’t me; but it had to be me! I was aware of what was happening around me, and then I was not.

I went through several such stages in rapid succession. I was in shock and passing in and out of consciousness. During one of my aware stages, I heard two of the infantrymen whispering about the continuing fire over the river, our drift and whether it would be safer in the boat or the water. I tried to listen, hindered by the still thunderous rapid fire. I was able to bury my head in a nearby helmet, believing it would protect me as I passed into unconsciousness again.When I came to, several men were in the water clinging to the boat. All else in the boat was quiet, not a sound. The firing continued, but sounded distant, either because it was, or in my altered state of mind it just seemed so. The limbs and torsos I seemed to be a part of were motionless. I wondered if they were dead or alive, or like me, hurt and unable to think clearly, and too afraid to move or even breathe.

I thought if those in the water felt safer there I should do the same. I hardly remember leaving the boat, but I did. When one’s life is in jeopardy, there is a hunger for survival and few things are impossible. I never considered it was March, and the river was cold.

I have no recollections about my time in the water. We were drifting downstream in the fast current. I was aware enough to realize I was blacking out again, and my grip on the boat was faltering. I asked the figure next to me to help me back in and told him that I was hit and passing out. He pushed and shoved me over the side and back into the boat with little help from me. I promptly lost consciousness again.

When I came to next, I heard the men in the water talking about being away from the main lines of fire, but we were drifting to the German-held side of the river. They were not happy about this and said so in no uncertain terms. After a time, our boat reached the east bank, and the men in the water nudged it onshore.

National Archives |

| Five miles to the north, 89th Division GIs attempt to cross the Rhine at St. Goar. The Oberwesel crossing went well, but the attempt to breach Germany’s last great western barrier at St. Goarshausen, recalled Oscar Friedensohn, did not go according to plan. |

The landing spot was a steep, angular slope of cobblestones, part of an embankment that flattened out to a road. The angle was such that we had very good cover. That was a lucky break because there was a machine gun or 20mm gun just to our north. Because of the angle, the Germans could not see us. They were firing over us and across the river.

Fellow soldiers helped us, and one other engineer who also was hurt, onto the embankment. We all lay there — three uninjured infantrymen, including the lieutenant, and two wounded engineers. Ten of the 13 infantrymen who had piled into my boat and one of three engineers were gone. Some bodies were in the boat, but most had been blown away by the hellish fire and had gone down in the river, to be listed as missing. We, however, were temporarily safe, at least from the gun above us.

It was difficult remaining conscious. I was soon rudely yanked back by explosions to our south. This was American mortar fire probing the German positions on the hills above. These bursts, which frightened us because they were so close, seemed like child’s play when they were followed by larger artillery bursts in the same area. We feared that a round might fall short and land right on us. Throughout all of this, flares lit the river gorge, turning night into bright sunlight.

Lying there on the slope, I remembered that the first-aid pouches on our cartridge belts contained a small plastic case of sulfa tablets to be taken when wounded. I even recalled that a lot of water was needed when the tablets were taken. I asked the soldier next to me if he could get a belt out of the boat. He crawled down and returned with kit and canteen. He snapped open the kit and pulled out the sulfa case. I think they were the size and shape of aspirin tablets. The kit and case were saturated with water, and the tablets were gooey, a liquefied paste. It was impossible to extract any.

Neither of us knew how often to take them, so still in my shocked condition, I took the entire case in my mouth, sucked out the sulfa residue in one fell swoop and drank as much water as I could. Then the five of us fell silent. I was in and out of consciousness after this, hallucinating several times. The line between reality and hallucination was a thin one. I was almost certain German planes came in, flying low through the river gorge. I later learned that these were among the first jet aircraft used.

Sometimes, in my conscious moments, I thought we could never survive and I would die. I became resigned to this and was calm. Moments later, I felt we were on the edge of rescue and would be spotted at daybreak. Then I thought we wouldn’t be seen and would be left to our fate. And then I thought our own mortar or artillery would get to us first. At these times I panicked, my heart racing, nearly exploding in my shocked body. I sweated and shivered, and cursed the bad luck, the darkness and the visible lines of tracers. These, combined with fear and shock, made the trauma real, the thoughts not so.

While these moments came and went, the war went on. The lieutenant crawled over to me and asked if I could handle a Browning Automatic Rifle. I had trained on it and said so. He said that I would need it to protect myself and my comrade when he and the others left. One of them had taken the BAR out of the boat, and it was handed to me with several clips of ammo. I was lying on my back, as I had been since coming ashore. I tried to turn over to place the gun on its bipod, but found myself unable to do so. My entire left side would not respond to my intense desire to accomplish this easy task, and my right side was no better. The lieutenant saw me struggle, recognized that I could not get into the prone position needed to use the weapon and told me to do the best I could. As he started to crawl away, I asked where they were going. He said they were going to take St. Goarshausen, the objective of the attack. More than 600 men, almost a full battalion, were supposed to do this. Yet here these three American soldiers were still committed to taking the town. None of us knew how many of the original force were still alive, and here was one young American officer and two teenagers ready to take on this impossible task.

The three slowly crawled along the steeply angled bank to about 20 yards away. During the several minutes it took them to cover this distance, I struggled to turn over. Nothing worked. I became resigned to the threat from the cliff above. What would be, would be.

Then we heard it! All of us at the same time. A DUKW, a large powered amphibious truck, was heading directly toward us. I thought at the time that this was a miraculous coincidence. I suspect now that we were spotted in the flare-lit river, and the rescuers were meant to save this pathetic group cut off in enemy-held territory. The gun above was firing at the DUKW, and the little geysers of water spouts traced its path. It was too fast for the gun to be brought to bear on it, and it touched shore at our feet. Out poured what looked like the entire Army. The soldiers, their rifles at the ready, hit the embankment and went prone on the cobblestones, spreading out as they did so.

I asked if there was a medic with them, and when told there was, I called for him. He crawled to me, and I told him where I was hit. He went to work. He cut away my left pants leg and looked but said he couldn’t see anything. It was dark, and the cold river had washed away all the traces of blood. The Rhine must still run red from all the blood shed by Americans that night. He sprinkled a liberal amount of sulfa powder over my leg and told me he was giving me a shot of morphine. That done, he and a nearby soldier carried me to the boat. The morphine accentuated my drifting into and out of reality.There were two men crewing the boat, and they urged us to hurry because they wanted out of there now. One crewman wanted to use oars to start back, fearing engine noise would alert the Germans and draw fire. The other favored zipping across at top speed, and in my sorry condition I agreed with him. They quickly decided to use the motor. As soon as my squadmate was loaded, the motor roared, and the boat jumped away from shore at breakneck speed.

By the time the DUKW reached midstream, the German gunners had spotted us and a trail of bullet spouts was following us. As before, we moved too fast for the gunners to alter their line of fire, and the DUKW hit the west bank with a bang.A group of soldiers on shore jumped aboard to remove my friend and me. The crew were Navy, not Army, and they prepared to take another human cargo across.

I was carried up a long, steep path to the aid station on the top of the cliff. A couple of medics put me on the ground outside a house serving as the aid station. The triaging of the wounded started here. Someone soon looked at me, and I was moved inside the house.

Next I knew I was in an ambulance with three other casualties who were bantering joyously, happy to be moving away from the fighting. I was in no condition to join in. As the ambulance headed down the road, it was fired on, and the driver zig-zagged crazily to avoid the bullets. This was to be my last experience of actual hostilities.

I hardly remember getting to, being at, or leaving the evacuation hospital. The morphine given to me on the far bank had completely taken hold of my mind and body.

I do recall the next step in the Army’s hospital system — the field hospital. It was dark when I next awoke there on a litter on the floor of what looked like the lobby, alongside many other litters. I had been completely out of the world for more than 10 hours. I don’t recall much else, except that the next day I had a surgical procedure, and was then airlifted to Paris, where I was to spend the next three months as a patient at the 203rd General Hospital in St. Cloud, then a suburb of Paris.

It was there, after yet another surgery, that one of the physicians in the operating room said I was ‘very lucky, that I had the million dollar wound, no real permanent damage, but the war was over for me.’ The war was over for me, as it also was for all those who died that infamous night.

This article was written by Oscar Friedensohn and originally appeared in the April 2005 issue of World War II.

For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!