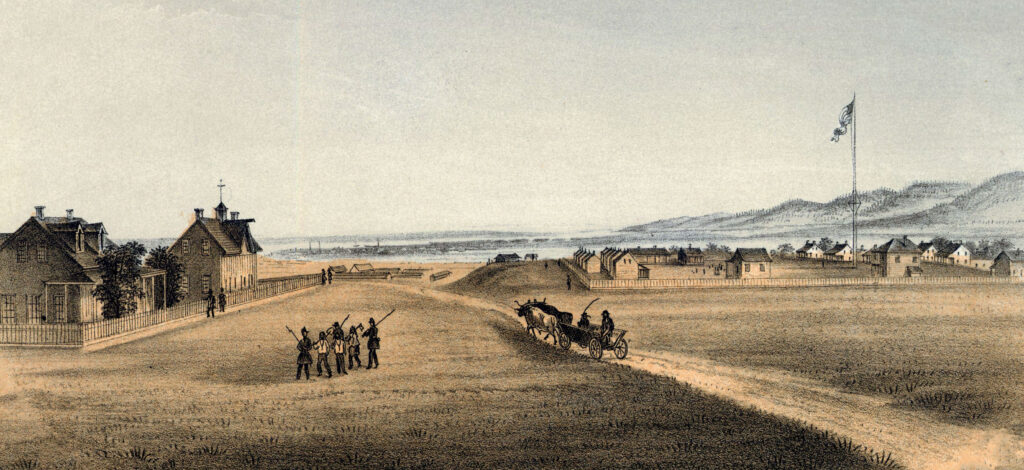

As Brig. Gen. Benjamin Alvord sat in his office at Fort Vancouver contemplating the operational season that had just concluded, he had every reason to feel satisfied about his first full year as District of Oregon commander. Almost everything he had asked of his forces, especially the 1st Oregon Cavalry, had been achieved. The only thing his mounted command had not done was largely out of its control: “chastise” the Snake Indians, more specifically the Northern Paiute. To accomplish that, as regimental commander Colonel Reuben Maury could point out after two years, one needed to find them first.

During the winter of 1863–64, Alvord mulled over how to make certain the Oregon Cavalry found the Snakes. On February 10, 1864, he mapped out his plans for the coming campaign in a letter to Oregon Governor Addison Gibbs, telling Gibbs: “I shall recommend to the general commanding the department [Department of the Pacific] that troops be sent to traverse thoroughly the whole region” from Canyon City to the California border, and as far east as Fort Boise.

While the Oregon Cavalry had spent the past two summers and falls in the field, Alvord planned to deploy them differently in 1864. “I hope to put two expeditions in the field the whole season for that purpose against the Snake Indians…,” he detailed. “I shall also recommend a movement from Fort Klamath easterly; but as that post is not in my district I cannot speak so definitely in reference to it.”

The plan was textbook military strategy: Alvord’s concept was to constrict the open spaces as the various Oregon Cavalry companies moved toward each other. If all worked well, one or more of those contingents would finally have the clash they sought with Chief Paulina’s band of Northern Paiutes. This differed in two ways from what the Oregon Cavalry had done the previous two years. First, the operations area would be shifted; instead of spending most of their time from Fort Boise eastward, along the immigrant trails, they would operate in eastern Oregon and western Idaho Territory, south of Canyonville, Ore. Next, this would entail multiple expeditions taking place at the same time.

With the three-year enlistments of most of the Oregon cavalrymen set to expire between December and March, this was likely the troopers’ last chance to prove their loyalty to the Union. Alvord was empathetic, knowing the “ardent desire of many of them would be to join in the war in the East.” Since that had never been possible, a well-coordinated military campaign to stamp out any Indian raiders along the immigrant trails was their only chance to prove their patriotism for the larger Union cause.

Raising a Loyal Regiment

It had been more than two years since federal officials finally decided to raise a regiment of Oregon volunteers to replace the departing Regular Army units in the District of Oregon. From its origins, the 1st Oregon Cavalry was different than the Union’s other volunteer commands. Not only would its service be different, the manner in which it was formed also differed from other volunteer commands. While governors in other states played prominent roles in raising regiments by appointing officers to lead them, that was not the case in Oregon.

From the start of the war, federal officials had concerns about the loyalty of Oregon’s governor, John Whiteaker, who had supported John Breckinridge’s presidential candidacy in 1860. Since the start of the secession crisis, Whiteaker had made a number of public statements supporting the South’s right to leave the Union. Those comments culminated with a set of lengthy remarks that were widely circulated in the Oregon newspapers in June 1861. Not only did the South have the right to secede, but, according to the governor, the Confederates had the right “if need be, to use every just means within their power to defend themselves, their property and institutions, against the unjust encroachments of the North.”

As the Army authorized the raising of a regiment of Oregon volunteers, the only question was whether Whiteaker was a Confederate sympathizer or just a local Copperhead. One regional newspaper editor felt Whiteaker was the former, calling him “as rank a traitor as Jolane [Joe Lane],” the former Oregon senator who ran as the vice presidential candidate on John Breckinridge’s ticket. Federal military and political officials in Washington, D.C., agreed and decided they would not work through the governor, opting to maneuver around him. Doing so was not an easy matter, even as his popularity eroded considerably throughout the summer.

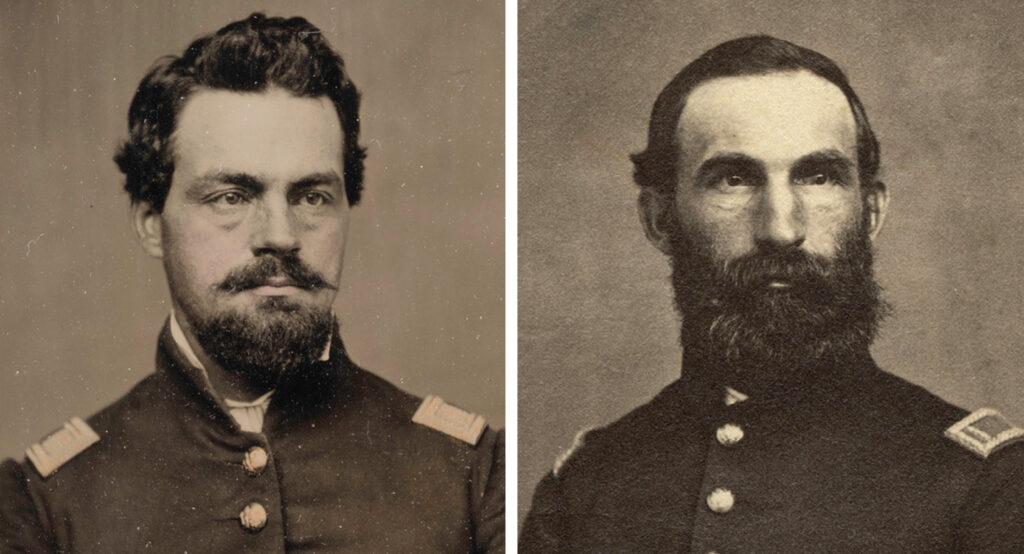

The political and military leaders in the U.S. capital had not circumvented a governor before and did not have a clear alternative in place. They knew they needed to ensure that any Oregon Volunteers were led by men loyal to the Union cause, but they were not sure how to go about it. So, on September 24, the adjutant general of the Union armies informed Thomas Cornelius, Reuben Maury, and Benjamin F. Harding they had been selected, “upon the strong recommendation” of Oregon Senator Edward Baker—President Lincoln’s dear old friend—who “relies confidently upon the prudence, patriotism, and economy with which you will execute” the raising “for the service of the United States one regiment of mounted troops.” The three men were informed they would “be governed by any directions sent to you by Col. E.D. Baker, and will under all circumstances report your conduct to the premises of the War Department.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Senator Baker’s role ended abruptly on October 21, 1861, when he was killed at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, Va. Upon his death, the challenging task of recruiting what became the 1st Oregon Cavalry fell solely to the trio in Oregon. The difficulties were exacerbated by the onset of the worst winter in a generation. Desperate to put a large mounted force in the field, the U.S. Army decided it could not wait to recruit a full complement of men, if it were even possible. In March 1862, the regiment formed with just six companies. A seventh company was added the following year.

For two years, the seven companies traversed thousands of miles in some of the country’s most inhospitable regions, from north central Oregon to southeastern Idaho Territory. At times, individual companies went into the field; at others, several served together for as long as seven straight months. They rode through mountain passes in the midst of snowstorms as late as June and as early as September, and across scorching high plains deserts. During those first two years, they had provided security for whites streaming into the Northwest, but they had not forced a large engagement on the various tribes they simply called Snakes. Despite their frustration, they were achieving part of the objective their leaders set for them—just not the one most of the troopers had sought. Alvord’s plan for 1864 just might give them the opportunity to finally prove, in the only way they could, “to the world, by acts rather than by words, our love and veneration for this blessed heritage bequeathed us by our [fore]fathers.”

Engaging the Paiutes

Four weeks into the 1864 campaign, Captain John M. Drake had nothing to show for his efforts except growing frustration over the numerous delays. As a result, the column had reached a point only about 125 miles southeast of his base at Fort Dalles. While he and some of his men took note of the vegetation and nature of the terrain they had ridden over, most of that land had been explored before. The fact his column had ridden on existing, though rough, roads most of the way, made it clear they had yet to explore any true frontier regions. Worse, given Alvord’s objectives, the only Indians the Oregon Cavalry had encountered during the campaign thus far were their own Warm Springs scouts. As his force continued southeast, he sent small patrols and some of his Indian allies fanning out on his forward flanks to find Paiute encampments or at least some indication they had been in the area. On May 17, that discovery occurred two miles below Drake’s camp, at the junction of the North Fork Crooked River and the main river channel. A Warm Springs scouting party that Drake subsequently sent out revealed a Paiute “camp about 12 or 15 miles [northeast] distant, numbering 9 lodges, and a large band of horses, 100 or more.”

Eager to engage the Paiutes, either in a confrontation of arms or to verbally impress upon them the cost of attacking Whites, Drake moved quickly. He ordered Lieutenant John M. McCall to make a night march to the site of the Paiute camp with a force including 26 of his own men from Company D; Lieutenant Stephen Watson and 10 men from Company B; and 21 Warm Springs scouts led by Stock Whitley. The objective was for McCall to surprise the camp in the pre-dawn hours, despite having no evidence they had done any raiding. Drake would follow with the rest of the command in the early morning.

At 9:30 p.m., McCall left Drake’s camp on the Crooked River and headed in a northeasterly “direction over an extremely rockey [sic] country for some 12 miles,” before coming to “the vicinity of the camp, where we found our [Warm Springs] scouts.” Traveling guardedly in the dark, McCall’s force did not reach his scouts’ location until about 2 a.m. He sent four Warm Springs scouts ahead to find the best way to close the mile gap between his men and the Paiute camp. The scouts reported they could close to within 500 or 600 yards without being discovered. McCall quietly moved his force as near as possible, noticing the camp was on flat ground, under juniper trees, with the Paiute horses herded together in two groups above and below the camp.

On his scouts’ advice, McCall decided to approach from the west, dividing his force into three groups. Watson would be in the center, as Whitley and his 21 Warm Springs scouts moved to the left and McCall advanced with Company D on Watson’s right.

The crucial coordination between the three columns—made more challenging in the dark—quickly unraveled after the advance started about 4 a.m. The eager Watson, who had the easiest path, quickly outpaced the other two wings. McCall’s men literally bogged down while crossing treacherous ground and then having to traverse “a quagmire” with some difficulty.

By this point the Paiutes, discovering they were being attacked by a force of undetermined size, sent a man out to gather their horses. McCall’s men drove the man off and “immediately secured these, and put them in charge of a corporal and two men.” The struggle through the quagmire and disorganization caused by capturing the horses left McCall well behind Watson’s group, although the Warm Springs scouts were making steady progress on the far left.

After detailing the three men to take charge of the horse herd, McCall moved the rest of his wing toward the Paiute encampment. According to McCall, upon hearing firing to their left, they turned to find “we were going directly under the fire of Lieutenant Watson’s men.” Shifting to the right to get out of the line of fire as they moved forward, McCall’s men “found Lt. Watson’s party all cut to pieces.” As Watson’s men emerged into the open, the Paiutes had fallen back to a defensible position among some rocks on the hill, where they fired both guns and bows. “Lieutenant Watson was the first to arrive in front of the Indians,” one of his men observed, “and on the first fire fell mortally wounded from his horse—two of his men were killed at the same time.”

Others were hit during the ensuing firefight, including five more troopers. A civilian named Richard Barker was shot in the thigh, breaking the bone, and one of the Warm Springs scouts was also hit. Their leader, Whitley, was struck at least four times. One of the bullets “entered just under his ear and came out of his mouth carrying away two teeth, another fracturing his collar bone.”

After emerging on the right, and out of the line of friendly fire, McCall “found on examination that the Indians were completely fortified in a cliff of rocks.” With both Watson’s troopers and the Warm Springs Indians receiving heavy fire and his own group of troopers starting to come under fire, McCall decided that if he was going “to save my wounded men and the horses, my only recourse was to retire to a safe place, and send for reinforcements.” At 6 a.m., McCall’s situation was precarious; he believed reinforcements were nearly 30 round-trip miles away. About 8 a.m., a worried McCall “reached what I considered a safe place” near a spring.

Fortunately for McCall’s force, Drake had led a patrol out of camp at the usual time, heading generally in McCall’s direction. Thus, Drake was already an hour out of his camp when he saw two riders “approaching at full speed.” Learning from the messengers—a trooper and one of the Warm Springs Indians—that Watson had been killed and McCall was in danger, Drake “and a detachment of 40 men” from Captain Henry Small’s Company G “proceeded with all possible speed to the scene of the conflict.”

Having ridden “at a plunging trot,” Drake arrived at McCall’s defensive position three long hours after the call for reinforcements had gone out. While his surgeon attended to the wounded, Drake rode the extra mile to the scene of the firefight. As near as Drake could tell the Paiutes had left in considerable haste about an hour before his arrival, leaving a large quantity of provisions and some equipment. They fled on foot because the Warm Springs scouts managed to capture the horse herd after the three cavalrymen fell back with the rest of McCall’s command, abandoning their prizes. Drake’s men also recovered the bodies of their dead comrades, who had been stripped and mutilated. The Warm Springs scout had been disemboweled and scalped.

After burning the Paiute encampment with “an immense amount of provisions, robes, saddles and plunder,” Drake’s men gathered the remains of their dead comrades and headed back to McCall’s position. From there, the wounded who were able to ride mounted horses while the two most severely wounded were carried on impromptu stretchers; they slowly returned to the campsite selected by Lieutenant William Hand, finally reaching it at 11 p.m.—in Drake’s words, “weary, tired and gloomy.”

May 19 “was consumed in the necessary preparations for the burial of our fallen comrades,” Drake recorded in his journal. “Their graves were dug side by side on a small knoll south of camp in the edge of the timber and the three bodies were buried with appropriate [military] honors.” The surviving Warm Springs scouts gathered their wounded and dead and returned to their reservation. Drake acknowledged “a sad feeling pervades the command on account of Watson,” who, according to one trooper, “was about the most popular officer in the regiment.”

Once their dead comrades were buried and the initial shock wore off, the camp was rife with talk about Lieutenant McCall’s conduct during the firefight. Most blamed him for the disaster. Drake, however, did not. While he repeatedly criticized his fellow officers when he felt they were not performing their duty effectively, he was pragmatic and restrained in his assessment of McCall’s actions. Drake told Lieutenant John Apperson: “I am not disposed to censure McCall in this matter at all. He obeyed his orders. I did not send him out there to get a lot of men butchered for the mere glory of the thing.”

Drake dismissed camp talk that McCall had not moved fast enough to relieve Watson’s force, noting that the Paiutes’ position was strong and they had already shown their ability to crush a frontal attack. Even criticism that he could have used his remaining force to pin the Paiutes in their position did not impress Drake, who noted McCall had no way of knowing how long it would take for help to arrive. In the meantime, “the wounded were groaning and writhing in their agony, and a man whose heart is not very hard, could not be blamed much for trying to alleviate their sufferings as much as possible.”

Drake’s command spent the next 17 days building a defensible supply depot before resuming the march deeper into southeastern Oregon. Once the depot was fully constructed, most of the troopers continued their march to meet up with Captain Currey’s eastern prong of the operation. While the meeting eventually occurred, neither Drake’s nor Currey’s columns (nor Lt. Col. Charles Drew’s third column) ever caught up with a large body of raiders. In October, after an arduous seven months, the Oregon Cavalry companies returned to their bases of operation—Forts Dalles, Walla Walla, and Klamath—with most mustering out when their enlistments expired during the winter.

“[T]he results achieved,” Captain Drake candidly admitted, “are not all that I hoped for at the beginning” of the 1864 campaign. In truth, it was the Paiutes who had defeated the Oregon Cavalry twice—one of those, near the Crooked River, was the bloodiest day of the Oregonians’ cavalry service. Though disappointed at missing their last chance, to “chastise” the Paiutes, the Oregon cavalrymen had, to a large degree, succeeded in their three years of service. Indian raids in the District of Oregon did not end during the war years, but the cavalry’s roving presence did at least provide considerable protection, especially for inbound immigrant trains. Had they failed, there would have been no choice but to redirect forces recruited for the main fronts of the war, as had happened during the fighting against the Sioux in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory in 1862.

There would be no national coverage of romanticized raids as there would be for Confederates such as J.E.B. Stuart or Union leaders like Benjamin Grierson. After gathering reports from several Oregon Cavalry officers in 1866, Cyrus A. Reed, the state’s adjutant general, concluded that even though serving in the Pacific Northwest was different than service elsewhere during the Civil War, the Oregon troopers were “ready and willing…to imperil lives in their country’s cause.”

Noted Reed: “[O]ur troops have not been idle; that a large scope of our country has been explored, which is now being settled under their protection, metals brought into circulation, and, I can say without fear of contradiction, that for long, and tedious marches, excessive privation and hardship, that our troops can produce as fair a record as any; still they have encountered a sufficient number of hostile Indians in every conceivable phase of attack to demonstrate how ready and willing they were to imperil lives in their country’s cause.”

Not long after the Oregon Cavalry’s defeat near the Crooked River, one of Drake’s men wrote to a Portland newspaper, observing bitterly that “though public opinion did not so vote, it was just as deserving of praise to die here in the discharge of one’s duty as it would have been to fall at Chickamauga or Gettysburg.” This was their war.

James Robbins Jewell, a frequent America’s Civil War contributor, writes from Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. This article is adapted from his latest book Agents of Empire: The First Oregon Cavalry and the Opening of the Interior Pacific Northwest During the Civil War (University of Nebraska Press, 2023).