When America flexed its imperial muscles in the South Pacific, a literal typhoon got in the way

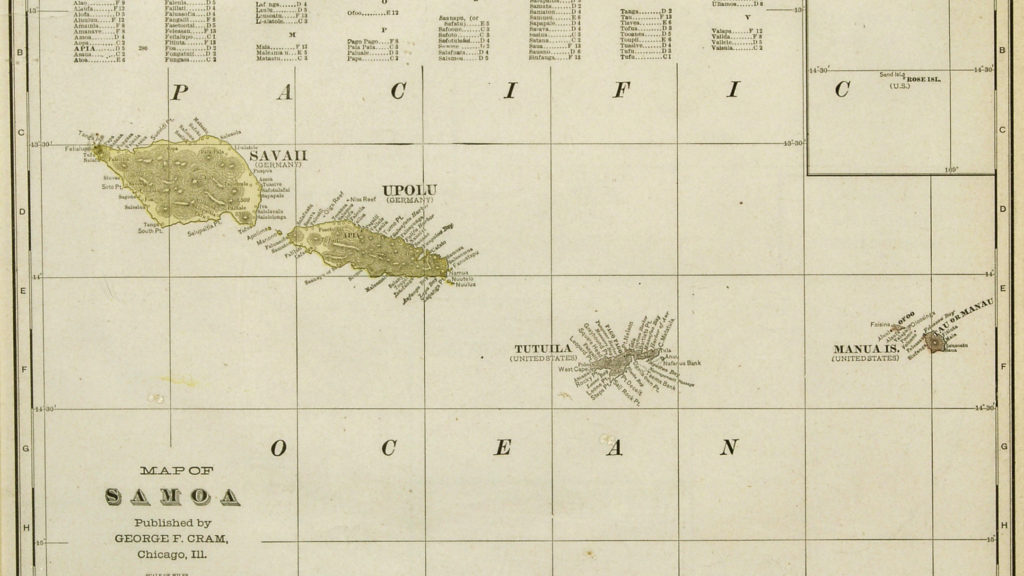

Apia Bay lies on the north shore of Upola or Upolu, the largest island in the South Pacific’s Samoa island chain. The bay, a lopsided, coral reef-encased V, is bounded by a peninsula on the west and a headland on the east. Through winter—summer in the South Pacific—Apia’s small harbor shelters vessels, its coral floor layered with just enough sand to hold anchors.

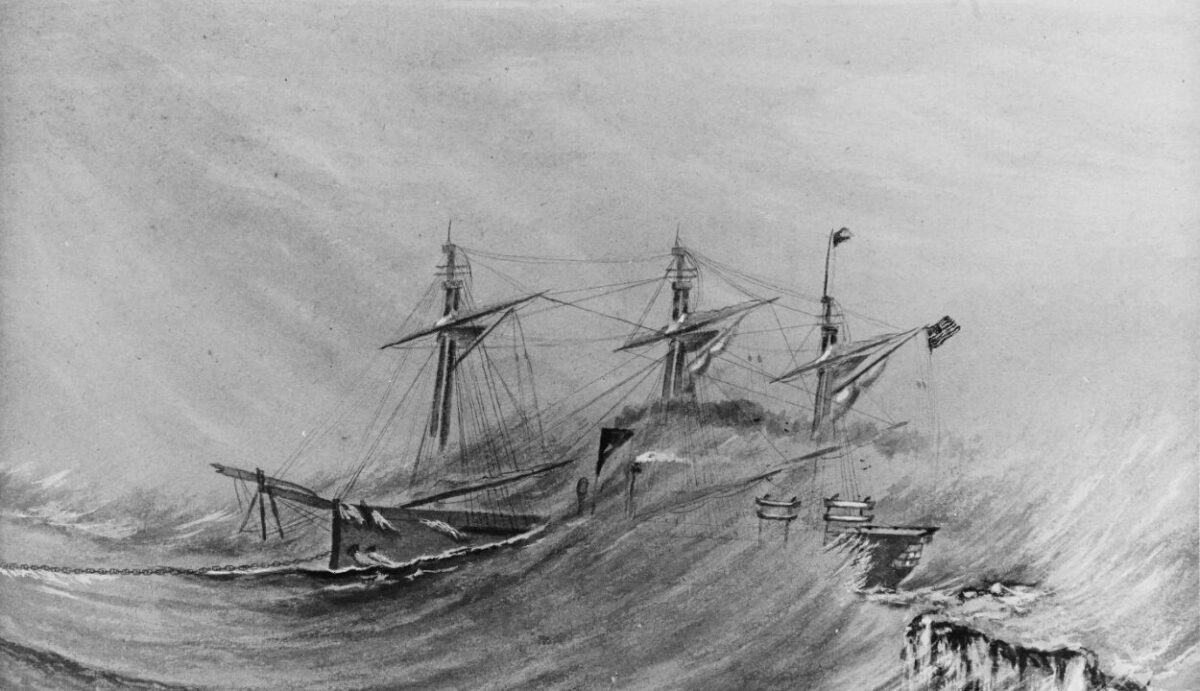

In spring, however, storms can turn the little harbor into a churning trap. Weather-wary skippers usually have time to make for deeper, safer water. But as barometers were plunging on March 15, 1889, Apia Bay remained crowded. Seven warships, each flying the flag of an ambitious nation, crowded the anchorage. The vessels’ hulls bristled with cannon and their crews eyed other crews with suspicion.

In spring, however, storms can turn the little harbor into a churning trap. Weather-wary skippers usually have time to make for deeper, safer water. But as barometers were plunging on March 15, 1889, Apia Bay remained crowded. Seven warships, each flying the flag of an ambitious nation, crowded the anchorage. The vessels’ hulls bristled with cannon and their crews eyed other crews with suspicion.

Germany’s commercial interests in Samoa dated back 30 years and included swapping guns for land on which to grow coconuts, coffee, cocoa and cotton. The German government had sent Adler, Eber, and Olga. Britain’s Calliope, a corvette, represented the empire’s ill-conceived scheme to incorporate Samoa and Tonga into the Crown Colony of Fiji. U.S. Navy ships Nipsic, Trenton, and Vandalia advertised America’s lesser imperial yearnings: refueling and revictualing sites for its nascent Pacific fleet.

Eber, displacing 700 tons, lay closest in, a quarter mile offshore, facing the American consulate. Nipsic, 600 tons, was at anchor 200 yards east of Eber. Adler, 900 tons, was floating just beyond Nipsic; Olga 2,400 tons, and Calliope, 2,800 tons, just beyond Eber. Vandalia and Trenton, latecomers too big to anchor in the harbor proper, had dicier berths: Vandalia, 2,000 tons, a mile offshore, Trenton, 3,900 tons, just inside the breakwater.

Through January, Samoa’s weather had been unusually tranquil, in contrast to the shore, where tribal factions were warring, a near constant condition aggravated by foreign sailors’ raucous behavior ashore.

February gales caused three small sailing vessels—one German, two American—to founder. Winds on March 7 forced all warships to supplement anchors with engine power just to stay in place. International relations were likewise troubled. The Brits and the Americans were allying against the Germans, who were giving as good as they got, diplomatically. The tensions reached 2,500 miles east to Hawaii, where rumors that Nipsic and Adler had traded shots spurred German and American expatriates to brawl on Honolulu’s streets.

Tensions ran highest on each nation’s home turf. The American press railed at German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck for leaning on tiny, defenseless Samoa. “Outrages by German Authorities Unredressed,” a New York Herald headline screamed. The San Francisco Examiner proposed to “reduce Bismarck’s armada to a pile of Iron filings.” Bismarck’s consul in Cincinnati, Ohio, warned the homeland that, should conflict arise, “German-Americans would fight against the fatherland.” Germany had proposed a conference in Berlin to settle the Samoan troubles, but its admiralty also had asked for strategic direction on how to wage war against the United States.

In Samoa, worsening weather on the afternoon of Friday, March 15 made clear that every captain in Apia Bay needed to act. Crews of six smaller transports already had battened hatches, thrown out additional anchors, and fled their ships for shore. In a storm, standard warship procedure was to seek open water, but this group of captains, eyeing and defying one another, held to their moorings. Nature be damned; the smallest nudge in this tiny, remote harbor could trigger a global war.

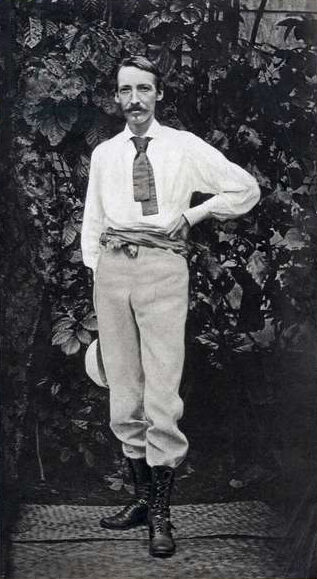

Subsequent events in Samoa found their most incisive chronicler in Robert Louis Stevenson. Author of Kidnapped and Treasure Island, the a Scottish-born Stevenson had acquired an American sensibility, crisscrossing the country by train, beachcombing Monterey’s dunes, honeymooning in an abandoned Napa silver mine, and wintering in the Adirondacks. In June 1888, he sailed from San Francisco to tramp the Pacific before settling in Samoa. Writing about the three-power tangle there, Stevenson gave his adoptive land the benefit of the doubt. “The United States have the cleanest hands” although “even theirs are not immaculate,” he wrote.

Fa’a-Samoa, the islands’ culture, revolved around clans. Inspiring orators—“talking chiefs”—led tribal councils. The most powerful clans conferred kingship and its accompanying authority—subject to reversal, dispute, and even armed conflict, including beheading of rivals. Fa’a-Samoa proved ripe for manipulation by American and European interlopers.

Samoa had caught America’s attention in 1839, when U.S. Navy explorer Captain Charles Wilkes (bit.ly/CrazyCommander) discovered the fine harbor at Pago-Pago, southeast of Upola. Pago Pago’s anchorage was ideal for servicing an emerging marine technology—the coal-fueled ship. International influence otherwise avoided Samoa until 1857, when a German firm set up coconut plantations in the islands. By then, U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan, but the specter of civil war at home discouraged American scientific, commercial, and diplomatic forays abroad. By 1869, with the Civil War over and the railroad opening the continent’s western regions, America again was looking seaward.

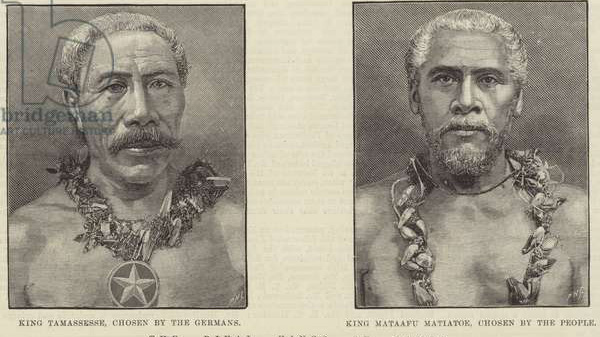

In 1878, on the strength of a Samoan chief’s ceremonial visit to Washington, the U.S. Senate ratified a friendship treaty. That pact promised America would intervene on Samoa’s behalf should differences “unhappily” arise between the island nation and another government. Not to be boxed out, Germany and Britain negotiated separate “most-favored” deals, entangling Samoans with three formidable papalangi—“sky-bursters,” as islanders called foreign powers. In 1881, Britain, Germany, and America brokered a Samoan succession in which tribal leader Laupepa became king, while rival Tamasese became “vice-king.” The arrangement, intended to stabilize Samoan politics, only roiled them further.

Distance from Washington—7,000 miles—London—10,000 miles—and Berlin—10,000 miles—only made matters worse in Samoa. In the time it took resident papalangi to receive formal instructions and dispatch official reports by ship to a telegraph station at Auckland, New Zealand, 1,500 miles distant, these rival consuls, naval officers, shopkeepers, and plantation managers acted out of passion and self-interest. For example, German papalangi, with Bismarck’s warships to back them up, undermined Laupepa and elevated the more pliant Tamasese. With its “commercial sharpness,” Germany was dominating Samoan commerce and was “prepared to…overthrow inconvenient monarchs and let loose the dogs of war,” wrote Stevenson.

In January 1885, the Germans ousted Laupepa, proclaiming Tamasese king of Samoa. The American and the British protested. Tamasese’s unpopularity spurred Mataafa, another chieftain, to ally with the deposed Laupepa and 6,000 more loyalists in an armed insurgency. After much foot-dragging, the three Western powers agreed to confer in Washington. That summer 1887 conclave was adjourning inconclusively when Germany upped the stakes in the South Pacific. Landing the Kaiser’s troops on Upola, German Consul to Samoa Wilhelm Knappe demanded Laupepa’s immediate surrender and $13,000 in reparations for property damaged by insurgents. Forlorn, Laupepa huddled with supporters. “We have no cause for shame,” one advisor said. “We do not yield to Tamasese, but to the invincible strangers.”

Laupepa surrendered and promptly was hustled aboard a German warship. The deposed ruler began a meandering west-bound voyage to Hamburg, Germany with stops in Australia, South Africa and the Cameroons. From Hamburg a train took Laupepa to Bremerhaven to begin another epic journey, this time via Gibraltar, the Mediterranean, Suez, the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean. That course landed the Samoan in exile at Jaluit in the Marshall Islands, roughly 2,000 miles northwest of his home islands. Laupepa’s followers thought he had vanished beyond the sky.

Amid the Mataafa insurgency, Knappe and cohort feigned neutrality. By December 1888, with Tamasese’s battle losses mounting, the consul was urging Fregattenkapitän E. Fritze, commander of the resident German naval squadron, to disarm the insurgent Mataafa. A plan jelled. Parties of German sailors, one from Olga, the other from Eber—150 men in all—would land on either side of U-shaped Vailele Bay, east of Apia. While the Eber men scoured west along the coast to Apia, disarming all Mataafans they encountered, Olga men would do the same on a sweep inland behind Apia. Word of the plan leaked immediately. “Tomorrow,” Tamasese warriors taunted Mataafan adversaries, “our guns shall be made good in broken bones.”

Mataafans mustered along Vailele Bay’s shores, accompanied by John Klein, a bellicose English-born correspondent for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

On December 19, the 90 sailors assigned from the Olga to fight on land crowded a flat-bottomed craft. The moon was nearly down but Samoans goaded by Klein spotted them. The ferry, “almost sinking with men,” was near the shore. “Do not try to land here!” Klein shouted. “If you do, your blood will be upon your head.”

The ferry changed course, gliding along as Klein and Mataafa warriors raced ahead, rousing reinforcements. A German plantation manager named Hufnagel signaled the ferry to land at a place called Fangalii. As the sailors waded ashore, Mataafa’s men fired from the tree line. A sailor fell. The Germans returned fire, then dove for cover.

Across the bay, Eber’s 50-man invasion force was preparing to debark from small boats near Sunga, site of another German plantation. Under fire, sailors vaulted overboard, using the boats for cover as they splashed ashore and sprinted to a warehouse.

The action at Sunga triggered fresh volleys at Fangalii. Germans advanced inland but Mataafans filled the woods. Three fierce German charges parted the Samoan lines, allowing the Olga landing party to take shelter in Hufnagel’s residence. From three sides, Mataafans fired wildly but prodigiously, riddling the house. As insurgents crept closer, German sailors flung open doors and dashed out, guns blazing and bayonets flashing. Germans were able to rout Mataafa pockets, but other insurgents closed on the enemy flanks.

With German casualties at Fangalii and Sunga tallying 46 dead and wounded, Eber charged in as close in as his ship’s 12-foot draft permitted, firing its three 6-inch rifled cannons. The Mataafans retreated. Eber recovered both landing parties. But, Stevenson noted, the skirmishes had sapped the Germans’ supposed invincibility. “[Conceive] the elation in any school” if the head boy “should suddenly arise and drive the rector from the schoolhouse,” he wrote.

Samoan resistance outraged the Germans. Mataafa warriors, fighting Europeans as they would one another, lopped off two German heads. A splenetic Knappe lost control. The consul proclaimed a state of war, imposing martial law. He vowed to search incoming vessels regardless of flag, and demanded that Klein, who’d fled to the American consulate, surrender for trial. When after several week news of the violence finally reached Washington and London, both countries ordered warships to the scene. Sailing from New Zealand, the British corvette Calliope, skippered by Captain Henry Kane, reached Samoa on February 2. San Francisco-based USS Vandalia and Panama-based Trenton, both weighed anchor on December 20 under the overall command of Rear Admiral Lewis Kimberly. Vandalia and Trenton arrived about three weeks after Calliope. As the long-brewing standoff was intensifying, a great storm came on.

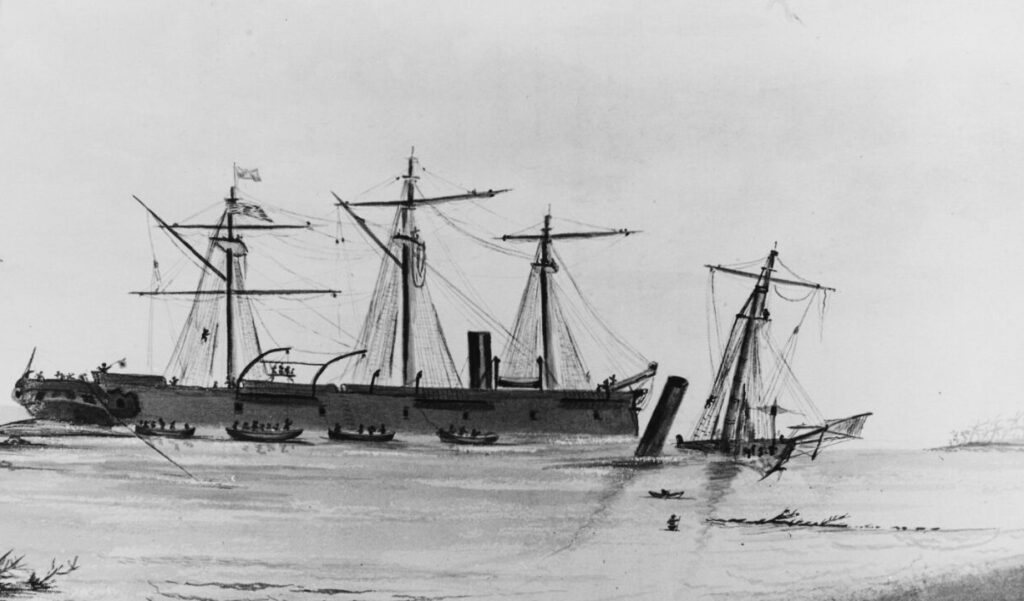

Just before daybreak on March 16, 1889, the harbor at Apia was boiling under dark clouds and squalls. Gales blew straight in. Massive waves buried vessels or stood them on end. Only Trenton, farthest out, was holding its place. The rest were tossing at close range, each threatening to ruin itself and others.

About midnight, with the harbor bottom scoured of sand, Eber dragged its anchor. Vandalia did so an hour later. By 3 a.m. all ships in the harbor except Trenton were unwillingly on the move. Sailors clung desperately to rigging as ships careened. Gunboats Eber, Adler, and Nipsic were closest together, only yards off the reef. Suddenly, Eber shot forward, prow smashing Nipsic’s port quarter and carrying away deck railing and a small boat.

Eber caromed off Olga. Neither ship sustained damage, but Eber lost momentum, moments later swinging broadside to a wave that carried the German vessel onto the western reef. Slamming down with terrible force, Eber briefly rolled toward the sea, then disappeared along with nearly all its 80-man crew. “Conceive a table,” Stevenson wrote. Eber “had been smashed against the rim and flung below.”

At 6 a.m., Adler’s mooring lines entangled with Olga’s. Adler’s skipper had men release that ship’s mooring lines. Propelled west and broadside by surf, Adler rode a wave onto the reef where Eber had disappeared. However, Adler landed well away from the reef’s rim, rolling entirely on its side, its back broken but its decks facing shoreward.The German ship had been, wrote Stevenson, “tossed up there like a schoolboy’s cap upon a shelf; broken like an egg.” Many among Adler’s 100-man crew were washed overboard. Most, including squadron commander Fritze, landed in shallow water on Adler’s wind-sheltered lee and found handholds on the ship’s guns and masts.

Meanwhile, bluejackets aboard American gunboat Nipsic strained to keep their ship from suffering the fate of Eber and Adler. Nipsic was running a full head of steam, bow straight into the wind, and looked to be clearing the reef when lookouts saw Olga bearing down. Nipsic avoided that collision, but Olga swung to strike Nipsic amidships, splintering railings, carrying away more boats, unseating the mainmast, and toppling the American ship’s lone smokestack.

Losing steam, Nipsic skipper Commander Dennis W. Mullan decided to beach. With Nipsic’s bow now aimed shoreward and one anchor hauled in, the ship’s engineers, short of coal, were stoking the boilers with boxes of salt pork. Nipsic skirted the reef but grounded itself 15 yards from the water’s edge where current collided with rampaging river water to create a deadly whirlpool. In a display of bravery, brute strength, and total disregard of earlier hard feelings, Samoan rescuers edged waist deep into the vortex, forming human chains to haul Nipsic survivors ashore.

Most Nipsic crewmen remained on the 200-foot gunboat’s forecastle. On lines passed to Samoans, American gobs advanced singly to shore, often submerged. Skipper Mullan, a Kentuckian who could not swim, went last, improvising a lifeboat out of a buoyant water casket. All hands ashore focused on Eber’s disappearance, Adler’s peril, and Nipsic’s deliverance until 9 a.m., when Vandalia, Calliope, and Olga seemed poised to collide. Calliope was nearest in, with Vandalia just off to port and a little ahead, and Olga very close to starboard. Vandalia clapped its stern under Calliope, severing the British ship’s bowsprit, demolishing Vandalia’s poop deck, and badly injuring the American captain. To avoid demolishing Vandalia, Calliope skipper Kane ordered engines stopped and reversed. The corvette came within 10 feet of the reef. Kane’s only escape was the open sea. Signaling his chief engineer to deliver every possible pound of steam, he ordered full speed ahead.

Water was cascading into Vandalia through the hole where the poop deck had been. Skipper Cornelius M. Schoonmaker was knocked silly and left bleeding, so command passed to executive officer Lieutenant James W. Carlin. Carlin, 25, did as he had seen the Nipsic’s crew do. He had topside deck hands—among them Midshipman John A. Lejeune, later a U.S. Marine Corps commandant—disconnect two anchor chains. Below decks, Chief Engineer Albert S. Greene kept the fires up and the engines churning. Vandalia was nearly four times Nipsic’s size, and Carlin had to steer even closer to the reef. Around 11 a.m., Vandalia grounded about 40 yards from Nipsic. Broaching in deeper water and broadside to the gale, Vandalia flooded and settled, driving men into the rigging. The injured Schoonmaker was clutching a railing when a wave swept him to his death. The sea carried Greene overboard three times. He made it to Nipsic, where other Vandalia survivors had taken shelter, and grabbed a line to which he clung briefly before being swept into the whirlpool, from which Samoans far out on Nipsic’s life-saving human chain plucked him.

Nipsic’s stern swung seaward to within 20 yards of Vandalia. A volunteer from shore climbed aboard Nipsic and heaved a line to Vandalia. A sailor secured the line, a lone link from Vandalia to Nipsic to shore.

Aboard Trenton men battened hatches, lowered yardarms, unfurled storm staysails, raised steam, and ran out anchors to reduce strain. With all hands on the top deck and in the rigging and Captain Norman von Heldreich Farquhar at the conn, the frigate rode out walls of seawater and pummeling rain. At 7 a.m., according to Rear Admiral Kimberly, sea and wind snapped Trenton’s rudder and carried away the wheel. Only anchors, storm staysails, and the men aloft, serving as human sails, were keeping the ship pointed north. Within the half hour, the sea had smashed holes in the main deck and the gun deck. If no one plugged those breaches, all was lost. Trenton’s crew stuffed the openings with tables, canvas tarps, mattresses, and hammocks as the ship’s anchor cables parted until only one, on the starboard side, was intact.

As Calliope began heading seaward, around 10 a.m., Trenton’s furnaces went out. In relays, seamen roaring the old chantey “Knock-a-Man-Down,” hand-pumped, barely keeping up, as the sea was pouring in through hawse pipes, too. At 3 p.m., while Trenton’s sailors pumped and prayed, lookouts aloft spotted a large black hull approaching. Calliope was muscling north at 15 knots against a countercurrent nearly as fast. Rising and dipping to its full length, its port flank a whisper from the reef, Calliope slowly came abreast inboard of Trenton. The two, sideswipe close, crept past one another. “A man on our lower yard could have clasped hands with one of hers,” said Kimberly, whose men yelled encouragement.

As Calliope was so narrowly clearing Trenton, Farquhar joined Adler’s, Nipsic’s, and Vandalia’s skippers in accepting reality. With Kimberly’s permission, Farquhar had sailors hoist Trenton’s storm ensign and feed out the last anchor cable. Trenton backed deep into the anchorage.

Olga—the only ship in the harbor at Apia still attempting to maneuver—was in Trenton’s path. Olga skipper Ehrhardt avoided one collision but could not keep his vessel from twice striking Trenton‘s bow, demolishing davits and lifeboats aboard the other ship and severing two of Olga’s anchor cables. Ordering all moorings slipped and full steam ahead, Ehrhardt skillfully steered Olga aground a headland bordering Apia Bay’s east side, later signaling that ship and crew were safe and secured.

Trenton’s hull began skidding along the coral bottom of Apia’s harbor, finally grinding to a halt close beside Vandalia, visible only as masts, bowsprit and forecastle. The grounded Trenton offered a landward transit for Vandalia’s stranded crew. Lines carried to Vandalia by rocket let men flee Vandalia for the other ship and then the shore. A muster found 43 Vandalia sailors missing but only one Trenton man gone.

The storm raged all night, banging Trenton against Vandalia. Dawn brought quiet and a portrait of devastation: Olga and Nipsic beached, Trenton sunk gun-deck deep and partly piled onto Vandalia, beach heaped with flotsam amid snapped masts strewn like jackstraws.

Samoans—uniformly expert with small boats—paddled through the surf to Trenton and with Americans rigged lines to rescue Trenton and Vandalia survivors. Mustering his crews, Kimberly paraded Trenton’s band. “The bay was suddenly enlivened with the strains of ‘Hail Columbia,’” Stevenson wrote.

Consul Knappe and fellow German landlubbers had feared all night that survivors of Adler might perish, but dawn showed the corvette perched high and dry, yet shattered, atop the reef. Instead of revenging themselves on Adler’s and Olga’s defenseless bluejackets, Mataafans defied the sea and Knappe’s 50 rifle-wielding German bodyguards to help save Adler’s crew, of which all but 20 men survived. All day Samoans impressed the “sky-bursters” with their virtue. Of “the almost inexhaustible harvest of the beach,” little was stolen and “much was very honestly returned,” Stevenson noted.

American and German sailors, however, soon reverted to pugnacious type. The town of Apia quickly split into German and American camps. Kimberly had armed sailors patrol his sector with orders to shoot unruly seamen and to pour off the booze and demolish the premises of any publican selling liquor to an American sailor. Manners grudgingly returned.

“The incongruous mass of castaways was kept in peace, and at last shipped in peace out of the islands,” Stevenson wrote. “Within a single day, the sword-arm of each of the…angry Powers was broken; their formidable ships reduced to junk; their disciplined hundreds to a horde of castaways… Both paused aghast; both had time to recognize that not the whole Samoan Archipelago was worth the loss in men and costly ships already suffered.”

Wishing to end the Samoan fracas, Bismarck insisted Germany had only commercial, not political interests in the islands. In truth, Germany was in no shape to risk war with America or to challenge England. To illustrate his intent, Bismarck ordered Knappe home in disgrace. The six-week, nine-session Berlin conference on Samoa that Germany had proposed was an anticlimax, Subcommittees easily resolved side issues, but the central matter—who would occupy the Samoan throne—proved thorny. Germany vetoed Mataafa, who had blood on his hands from Fangalii and Sunga. The Americans scorned Tamasese as the Kaiser’s puppet. In the end, the papalangi agreed that Laupepa, in his third year of exile, should be king of Samoa. The Final Act of the Berlin Samoan Conference, signed June 14, 1889, established a tripartite protectorate over the islands.

Of Nipsic’s 190-man crew, all but seven survived, while the ship, though battered, sailed again. The Samoa episode cast a strong shadow in Washington. In a first, America had been a coequal of Britain and Germany. Moreover, the loss at Apia of two American warships and damage to a third invigorated advocates of a two-ocean navy. By 1899, when unrest again rocked Samoa, the Berlin pact yielded to a partitioning of the islands between Germany and the United States, which in the few years since had parlayed a soft-spoken distant intervention into worldwide “big-stick” power. German Samoa eventually gained its independence in 1962. American Samoa remains a U.S. territory.