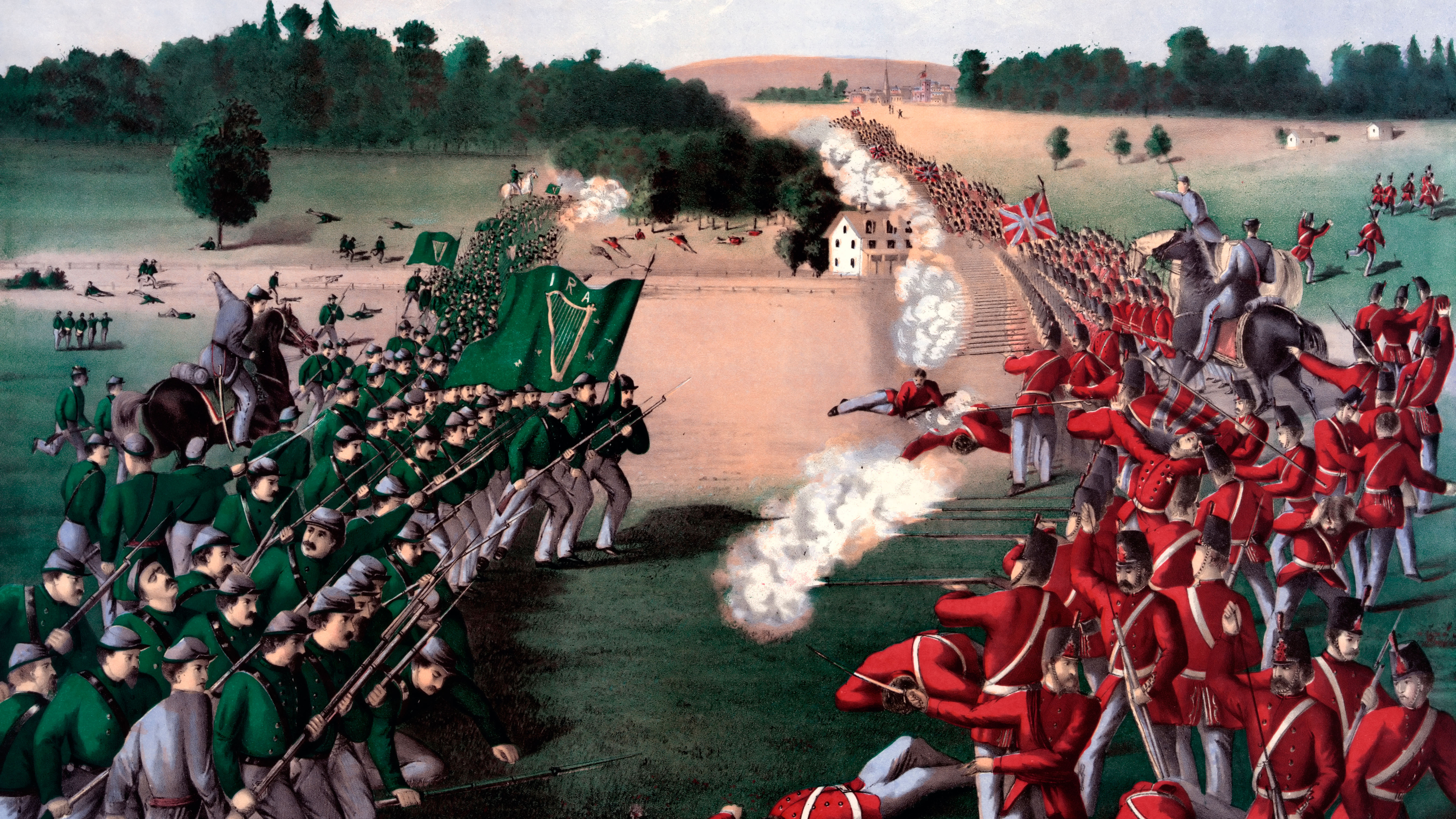

THE INVASIONS—launched before dawn on June 1, 1866—went unopposed. Hundreds of men at arms waded ashore by moonlight, cheering as they planted their flag. The invaders marched inland and, without a shot being fired, overran a town. To frustrate defenders, they burned a rail bridge and cut nearly every telegraph line. Waiting for reinforcements, the soldiers patrolled their newly seized domain. The flag was green. The enemy was Britain. The captive territory was a stretch of Canada across the Niagara River from Buffalo, New York. And the invasion force was Irish-American. The Irish Republican Army’s aim was to capture some or all of Canada and take hostage Britain’s largest North American holding. The ransom? Freedom for Ireland. To succeed, this ingenious but delusionary plan required the tacit complicity of the United States government—complicity the belligerents believed they had obtained.

They could not have been more wrong.

Since colonial times, America had drawn immigrants from Ireland. Opportunities in the early 1800s for work building canals and other projects pulled more Irish across what they called “the Western Ocean.” That flow grew dramatically during a famine caused by potato blight in the 1840s and after Britain’s crushing in 1848 of the Young Ireland nationalist movement.

By 1860, of 27.5 million people living in the United States, 1.6 million had been born in Ireland. Many of these newcomers burned to free the old sod from English rule, in place since 1536. In 1858, John O’Mahony, 41, a refugee from Young Ireland’s defeat, founded the Fenian Brotherhood, a New York-based group dedicated to the “liberation of Ireland from the yoke of England.” The name referenced the Fianna, warriors of Celtic folklore. Anyone born in Ireland and able to afford a $1 initiation fee and a dime a week in dues could join, as could “Friends of Ireland living on the American Continent.”

Along the Eastern Seaboard, Fenian chapters called “circles” proliferated, enriching the organization and enhancing its local political clout. Foreshadowing the emergence of machine politics, the Fenians became a national powerhouse, sometimes notoriously so. In 1860, New York City staged a parade feting Prince Albert Edward, Queen Victoria’s eldest son. Fenian leader Michael Corcoran, who commanded one of the city’s militias, refused to allow his men to march. The Civil War saw more than 150,000 Irish-Americans fight for the Union and 20,000 for the Confederacy. Irish-American units like the 69th New York Infantry Regiment, known as the Irish Brigade, fought flying the Irish republican flag and the Stars and Stripes. “Here comes that damned green flag again,” a Confederate officer exclaimed in 1862 at Malvern Hill, Virginia, as a Union regiment massed. Among his acquaintances, Andrew Johnson, the Tennessean who was his state’s wartime Union military governor, counted John O’Neill, an avid young Fenian serving in the Union Army.

The war brought American-British relations to a low not seen since the nations went to war in 1812. Dependent on Southern cotton, Britain allowed English armorers to supply the Confederacy. English shipwrights sold the South vessels with which to run Union blockades and attack Union ships as privateers. CSS Alabama, for example, departed Liverpool beneath a Union Jack that the crew flew until switching permanently to the Stars and Bars. In a global campaign, Alabama and ilk ravaged Union shipping. Confederate blockade runners ranged out of British ports, including anchorages in Canada, a hotbed of Confederate agents. After the war the United States sued Britain seeking more than $2 billion in reparations for arming and trading with the secessionists. The action came to be known as the Alabama claims case.

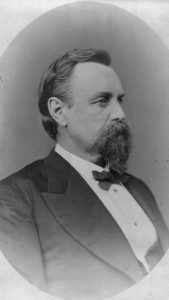

In mid-1865, the Fenians were riding high, politically strong and flush with more than $1 million in the bank. But the organization, from the start faction-ridden, was tearing itself apart. A faction led by O’Mahony wanted to ship arms and troops to Ireland to foment an uprising. Convinced the Royal Navy would quash any such effort, the moderate “Senate” wing, led by businessman William R. Roberts, argued instead to invade Canada. The idea was to hold that dominion hostage to force British concessions on Ireland—or trigger war between the United States and Britain, facilitating rebellion in Eire. The Senate wing prevailed and took over the Fenians.

Canada’s nearly 4,000-mile border with the United States was almost unfortified. Fewer than 10,000 British troops, augmented by inexperienced militiamen, garrisoned the dominion. Still, to seize Canada the Fenians needed American government support, in the form of latitude to launch, supply, and reinforce an invasion from American soil—a clear violation of the 1818 U.S. Neutrality Act barring Americans from participating in military action “against the territory or dominions of any foreign prince or state…with whom the United States are at peace.” However, relations between the United States and Britain were poor and Fenian ward heelers and precinct bosses were strong.“The old party wire-pullers know that the Fenians will wield great power in the fall and Presidential elections,” the New York Herald wrote.

At a meeting in the summer of 1865, Fenian treasurer Bernard D. Killian, a lawyer and newspaper editor, asked President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward how they would respond if Fenians invaded Canada from the United States. Cryptically, Johnson and Seward replied that they would acknowledge “accomplished facts.” Pressed later to declare himself in writing, Seward wrote that the government “expects to maintain and enforce its obligations and perform its duties towards all other nations.” Killian and fellow Fenians decided that Johnson and Seward meant that the American government would not interfere with their plans and would recognize any government the Fenians set up in Canada.

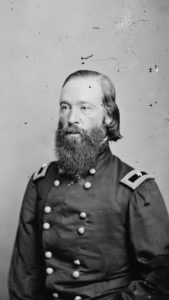

The Fenians named as secretary of war Thomas W. Sweeny, 45. A former U.S. Army brigadier general from County Cork, Sweeny had lost an arm in the Mexican War. At Shiloh, though wounded in his remaining arm, he had plugged a gap in the Union line, averting disaster. “I attach more importance to that event,” General William T. Sherman said, “than to any of the hundred events which I have since heard saved the day.”

Sweeny pictured Fenian forces crossing into Canada from points in New York, Michigan, Ohio, and Vermont to seize transport hubs and population centers. He envisioned raising a force of at least 10,000 men, mostly battle-tested Civil War veterans, predicting that they would be joined by Irish-born Canadians who “the sound of the first gun will bring into the field.” A unit led by William F. Lynch would cross the Niagara River at Buffalo and take nearby Fort Erie, Ontario. From that base insurgents would seize two rail lines at Port Colborne, 15 miles west, and capture the Welland Canal linking Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Personnel at U.S. Army arsenals at Frankford, near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and at Watervliet, north of Albany, New York, sold Fenians guns and munitions, a gesture the Irishmen read as confirmation of official backing. Their scheme was no secret. As early as October 1865, The New York Times was hinting at the Fenian plans. In March 1866, the New York Tribune predicted a St. Patrick’s Day strike. British informants soaked up intelligence as Fenians bragged of their plans.

Keen to keep Irish-American voters on his side as he wrestled with Congress over his Reconstruction proposals and intent on preserving the Alabama claim—an attack on a British holding from American soil would sink that suit—President Johnson refused to invoke the Neutrality Act or sanction an invasion. On March 12, 1866, U.S. Army commander General Ulysses S. Grant ordered troops to “use all vigilance to prevent armed or hostile forces, or organizations, from leaving the United States to enter the British provinces.” However, soldiers were not to interfere with Fenian gatherings. “During our late troubles neither the British Government or the Canadian officials gave themselves much trouble to prevent hostilities being organized against the United States from their possessions,” the ironical Grant wrote. “But two wrongs never make a right and it is our duty to prevent wrong on the part of our people.”

To some, the Fenians seemed more talk than action. Buffalo U.S. Attorney William A. Dart advised colleagues in Washington, DC, that “having collected such large amounts of money and made such boastful demonstrations of their intention to liberate Ireland they will be obliged to seek some excuse for their failure,” probably “a hostile demonstration which will fail or by inducing the government of the U.S. to make arrests and thereby frustrate their pretended designs.”

In April 1866, a few hundred Fenians crossed from Maine onto Campobello Island in New Brunswick, Canada—until the sight of British and Canadian troops sent them scampering back to the United States. On May 10, 1866, Sweeny ordered units in 16 states as far south as Tennessee and as far west as Missouri to pack “all serviceable army equipments [sic] and war material” for immediate shipment to embarkation points at the Canadian border. Fenian sympathizers near those sites warehoused weapons and ammunition labeled “gas fixtures” and “glass.” A week later, Sweeny ordered all units north, instructing his men to pose as railroad workers or newly discharged soldiers. Fenians in Buffalo rented canal boats and a tug to tow them, ostensibly for an ironworkers’ outing. Personnel were to “resist the seizure of any property of ours except the party or parties seizing show a United States warrant,” Sweeny said. “Pay no attention to State or Sheriff writs.” Men came from as far away as Louisiana, but Sweeny’s 10,000 did not materialize; at Buffalo, fewer than 1,000 mustered. In late May came the coded order: “You may commence work.”

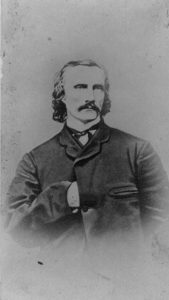

The invasion mostly misfired. A U.S. Army seizure disarmed would-be invaders in Vermont. Local commanders in Michigan and Ohio called off their operations, “whether from lack of transportation or disobedience of orders I know not,” Sweeny said. Only the 800-odd Buffalo contingent kept to schedule, and then in a reduced state. On May 31, U.S. Attorney Dart ordered Buffalo’s port closed by night, with craft departing by day to be searched. To patrol the Niagara River, 1,000 yards across at Buffalo, Dart could deploy the sidewheeler gunboat USS Michigan. However, to navigate the Niagara, the warship required the services of a local pilot. On May 31, that individual was incapacitated by a drinking bout with a Fenian-leaning Michigan crewman. The gunboat stayed docked, as townspeople watched Fenians load boats. They had vessels enough for 600; the other 200 men would stand by as reinforcements. The Buffalo commander, Lynch, failed to show. As a replacement, Sweeny dragooned Tennessean John O’Neill. O’Neill, now 32, had quit the army, irate at not getting a promotion. Sweeny provided neither written orders nor a map of the ground the force was to assault. O’Neill and his men believed there to be no British or Canadian troops within 50 miles. Putting in shortly after midnight, O’Neill’s troops landed about a mile downstream of Fort Erie and marched through the town. They burned a rail bridge to Sourwine and cut northbound telegraph lines, leaving intact a line to Buffalo to communicate with Sweeny. The invaders made camp about four miles from Fort Erie.

British regulars numbering 1,700 and commanded by Colonel George Peacocke were at Toronto, 56 miles northwest along the shore of Lake Ontario. At Dunnville, Ontario, 32 miles west of Fort Erie, were 850 Canadian militiamen under Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Booker. Alerted to O’Neill’s crossing, the British thought it a feint. Nonetheless, Peacocke ordered his troops, traveling by boat and train,to link up with Booker’s to crush any invasion.

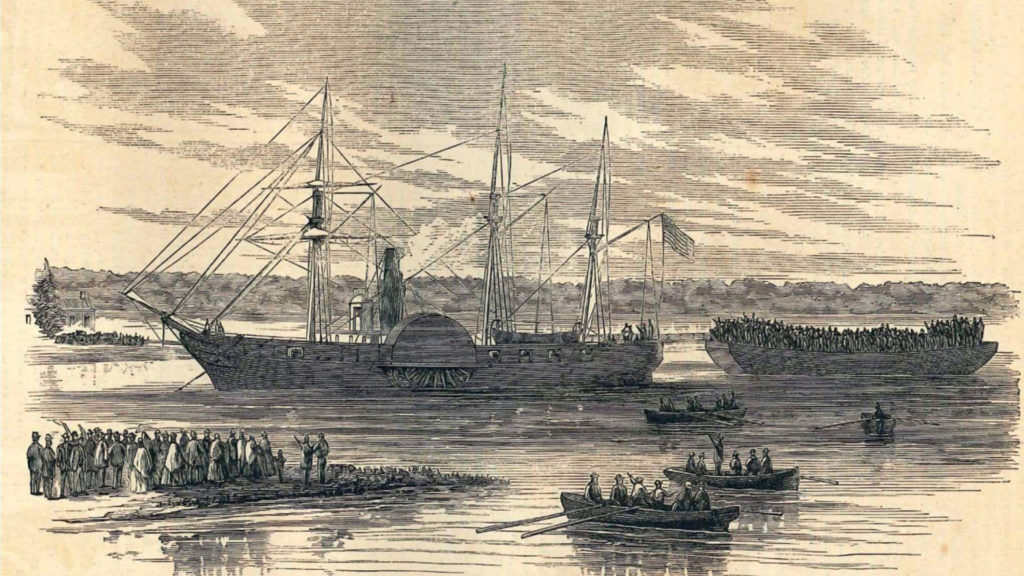

Told by spies and supporters that the enemy was coming, O’Neill overestimated his foes’ numbers by a factor of 10. Men deserted the Fenian camp for a tavern. “You blackguards!” O’Neill roared. “Do you think we brought you to Canada to get drunk, and make sport?” His force whittled to 500, O’Neill, thinking them badly outnumbered, wrote off Port Colbourne and the Welland Canal. He decided to engage the militia before they merged with the regulars. West of Fort Erie, on high ground outside Ridgeway, Fenian engineers fashioned fence rails into breastworks. In the morning, Booker’s infantry attacked. Two hours of battle had the combatants at a draw when Booker, described by a subordinate as “a conceited, arrogant, cowardly, nervous poltroon,” blundered. As O’Neill and his staff were advancing on horseback, Booker imagined he was seeing a cavalry charge. Infantry in such situations was to form a tight defensive unit, and the militia did. However, on open ground, that knot of bodies was easy pickings for a Fenian bayonet charge. The Canadians scattered, abandoning “muskets, overcoats, knapsacks, and other military impediments, thrown away to facilitate flight.” But Peacocke and his regulars were approaching, and the Michigan, guided by the now-sober river pilot, was prowling the Niagara, keeping Fenian reinforcements on the far shore. Near Fort Erie a 76-man militia outfit surprised O’Neill’s retreating force. A firefight ensued. Abandoning his troops, Canadian commander Lieutenant Colonel John Dennis hid in a house, donning civilian clothing and shaving his beard to disguise himself. Having killed four Fenians and wounded 19 to their six wounded, the Canadians withdrew. At Fort Erie, O’Neill swore he would make the palisade “a slaughter pen.” Instead, he wired Sweeny. “Our men isolated. Enemy marching in force from Toronto,” O’Neill told his commander. “What shall we do?” Fall back, Sweeny replied. Shortly after midnight on June 3, Michigan intercepted O’Neill and 317 Fenians mid-river. Invoking the Neutrality Act, sailors arrested the Fenians, who meekly submitted. His men “respected the authority of the United States,” O’Neill said. “We would have surrendered as readily to an infant bearing the authority of the United States.” Local authorities clapped the prisoners into cells at the Erie County courthouse.

Headline writers had a field day: “Bursting of the Fenian Bubble…The Invading Celts on Their Way Home…The Fag End of the Great Fenian Fizzle.” Wrote The New York Times, “The wild, Quixotic Fenian demonstration upon the Canadas has terminated, as every sensible person knew it would terminate, in failure and disgrace, but most happily with little loss of life.” The foregone conclusion, Army and Navy Journal declared, “was so apparent at the outset as never to find a single excuse or even an attempt at palliation, except from the men engaged in the scheme.”

Ever conscious of Irish-American political power, President Johnson ordered the Fenians released. His acquaintance O’Neill emerged from the courthouse to “great clapping of hands” and “loud huzzas” as he urged his men to “retire to your homes, peacefully and in an orderly manner,” journeys abetted by government-purchased rail tickets. On June 6, Johnson issued an executive order to deter illicit border crossings. He warned “all good citizens of the United States against taking part in or in any wise aiding, countenancing, or abetting” incursions, directing federal officials “to employ all their lawful authority and power to prevent and defeat the aforesaid unlawful proceedings.”

Johnson later told O’Neill that he had delayed acting to give the Fenians a chance at victory. “You must remember that I gave you five full days before issuing any proclamation stopping you,” Johnson said. “What, in God’s name, more did you want? If you could not get there in five days, by God, you could never get there.”

The dud invasion set off rounds of blame-laying. Fenian leader William R. Roberts took out after Johnson and the government. “If it had not been for the measures of the Washington Cabinet,” Roberts thundered, “there is no question that we would be in quiet possession of every foot of English territory on this Continent.” Claiming Fenian leaders had stampeded him, Sweeny said the British had bought off the American government. O’Neill blamed Sweeny for bad generalship and the Fenians for faintheartedness.

Mainstream Fenians moved on. O’Mahony, a foe of the Canadian adventure, turned to academic research. When he died in 1877, The New York Times called him “the one man whose unsullied name and repute as a scholar and a gentleman gave an air of respectability” to the Fenian movement. Sweeny rejoined the U.S. Army, retiring in 1870 as a brigadier general; he died in 1892. Senate wing leader William Roberts served two terms as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives representing the New York City borough of Queens.

Britain paid the United States $15.5 million to settle the Alabama claims and on July 1, 1867, Parliament authorized the colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec to form the self-governing Dominion of Canada. July 1 is celebrated now as Canada Day.

The fervent O’Neill launched several inconsequential border raids, the last in October 1871, when he headed north in the Dakota Territory with 40 men for what they thought to be the Canadian border. The insurgents misread their map, however, and the final Fenian stab at grabbing Canada occurred entirely within the boundaries of the United States of America.

______

Capturing Canada

The 1866 attempt to invade Canada cast a long shadow. Forty years on, American military planners began specifying secretly how the United States would handle hostilities should the nation, code name Blue, fight with Germany (Black), Japan (Orange), Mexico (Green)—or Britain (Red).

The 1903 war plans, periodically updated, mostly sought to defend the Western Hemisphere and American possessions. Plan Black focused on keeping Germany out of the Caribbean. Plan Orange anticipated a Japanese assault on the Philippines. Plan Green envisioned invading Mexico by land from Texas and by sea at Veracruz and Tampico.

Approved in 1930, Plan Red unconsciously emulated the Fenians by making Canada—code name Crimson—lead target in a British-American dustup. “CRIMSON is the only RED territory so situated as to afford BLUE an opportunity to strike a vital blow on land,” the plan noted. The effort would be all-out, with “chemical warfare, including the use of toxic agents…. authorized.”

American forces were to invade Canada “to separate CRIMSON from RED through the destruction of enemy forces in CRIMSON and the seizure of vital CRIMSON areas.” Planners saw the Atlantic making Canada easy pickings: “CRIMSON may be crushed before RED can reinforce her.”

Step one: seize Halifax, the Nova Scotia port to which the empire would try to send reinforcements. Step two: grab the Montreal-Quebec area, advancing into Winnipeg to split Canada east from west and “gain complete control of CRIMSON.”

America’s role as a World War I ally shrank but did not erase odds of war with Britain. “BLUE competition and interference with RED foreign trade” could bring conflict, with Britain making “every endeavor to provoke BLUE into acts of hostility,” American war gamers wrote in 1930. The scheme counted on anti-British sentiment among Americans. “The great majority of the BLUE nation possesses an anti-RED tradition,” planners wrote. “The BLUE government would experience little difficulty in mobilizing public sentiment in favor of a vigorous prosecution of the war…” though at home “a small number of pacificists [sic] and communists” were likely to protest.

In 1935, at a secret congressional hearing, a U.S. Army general mentioned without explanation that an airbase in the works near the Great Lakes needed its military function “camouflaged.” When news coverage spurred Canada to inquire, President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly repudiated the testimony. The Great Lakes base was scrapped. Plan Black fell by the wayside. Plan Orange morphed into the unsuccessful 1941-42 defense of the Philippines. Plan Red, shelved but never rescinded, remained secret until 1974.