An early and ambitious American scientific expedition developed a nightmarish side

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838 was a jumble of contradictions. Nominally, the six-vessel undertaking was to chart islands and reefs in the Pacific Ocean, collect specimens, and lay claim to Antarctica. But nationalism and geographical hokum—never mind wayward planning, haphazard execution, and the presence throughout of a borderline lunatic as a commander—rendered the effort better known as the Wilkes Expedition one for the books.

After the Revolution, American commerce in the form of sea otter and seal pelt traders and whaling fleets swarmed the Pacific. For decades, American ships and crews traveling the western ocean fell prey to uncharted reefs and shoals and hostile inhabitants of remote islands. Congress clamored to no avail to send the U.S. Navy to enhance navigation by conducting surveys and make the Pacific safe for vessels flying the Stars and Stripes.

In the 1820s, not a few Americans believed the Earth hollow, its interior accessible through portals at the poles. In 1823, English whaler James Weddell, sailing farther south than any man before, reported finding open ocean below South America. This persuaded American hollow-earther Jeremiah Reynolds that a passage to the earth’s core existed near the South Pole. New England congressmen were pressing for the Navy to start charting the islands of the Pacific. The politically savvy Reynolds, a popular lecturer, lobbied Congress to fund a single expedition with both aims. Reynolds urged fans to back his campaign. Deluged by demands to fund his scheme, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution requesting that President John Quincy Adams send a single vessel on the dual mission. Adams ordered the U.S. Navy to prepare 500-ton sloop of war USS Peacock while the House was authorizing funding for the expedition, to start in December 1828. However, Adams lost the election to the populist Andrew Jackson, who raged against Northeastern commercial interests. His allies in Congress derided the expedition as a costly indulgence, and by February 1829, though the concept lived on, the venture was dead.

In 1831, a piratical rajah in Sumatra allowed his brigands to plunder a Boston ship trading in pepper. The pirates killed several crewmen, prompting President Jackson to dispatch the 282-man frigate USS Potomac to Sumatra, an island larger than Britain. Reynolds wormed his way aboard as the captain’s civilian secretary. In February 1832, the frigate’s crew destroyed the rajah’s fort, burned his town, and killed more than 450 Sumatrans. The extent of the action brought complaints at home from anti-colonialists. Others said to leave retribution to the Dutch, in whose sphere Sumatra lay. In 1834, when Reynolds returned from the East, Jackson was still parrying criticism. Reynolds quickly published an article praising the president’s actions.

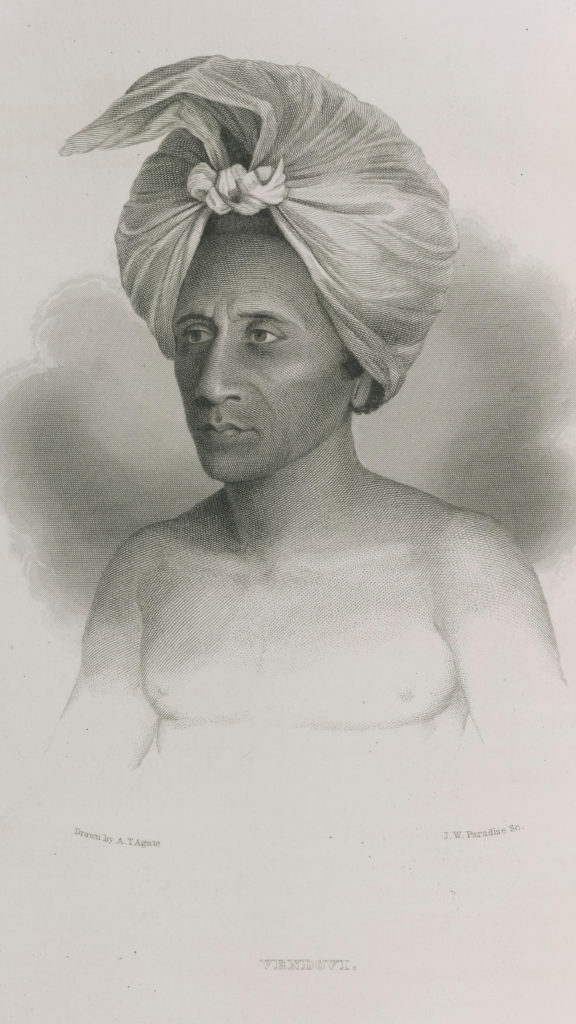

Simultaneously, maritime interests were petitioning Congress to deal with the Fiji Islands where, the year before, lack of charts had gotten the American whaler Charles Daggett lost. A local chief, Veidovi, attacked the vessel, killing and supposedly eating 10 sailors. Shippers wanted the U.S. Navy to punish the cannibals and chart the Fijis, where warriors customarily killed strangers setting foot ashore and in recent years unmarked reefs had sunk eight ships, including five from the United States.

An old friend of Reynolds, Senator Samuel Southard (W-New Jersey), headed the Committee on Naval Affairs. After much lobbying by Reynolds, Southard’s panel proposed to authorize a Pacific foray. On April 3, 1836, Reynolds spoke on the House floor, describing his dream of a naval squadron sailing the Pacific not only to carry the flag but to advance science. The expedition should include scientists to study natural phenomena, languages and customs, weather, navigation, the earth’s magnetic field, and the southern polar region, he said.

Jackson had appreciated Reynolds’s support regarding the Potomac episode. Tempering with practical nationalism his own conviction that the earth was flat and his hatred of the commercial class, the president let it be known he favored a grand stroke such as Reynolds urged. If any nation was going to discover new lands, it was going to be the United States, and scientific advances sure to come from the venture would enhance the nation’s reputation, Jackson told congressional leaders. Congress voted $150,000 for the cruise. On June 9, 1836, the aging president wrote that the expedition “should be sent out as soon as possible.”To lead the squadron, Jackson picked Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones, a comrade from the Battle of New Orleans disabled by a musket ball during the 1815 fight with the British.

The roster also included Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, 40, a six-footer beneath whose well-groomed brown hair a gaunt face bore scars from smallpox. Born into a wealthy New York family, Wilkes loved the sea. Shipping off in the merchant marine, he asked his dad to get him a U.S. Navy commission. There was no higher Navy rank than commodore, who commanded multiple vessels. Below that ranked a few captains, each in charge of one ship, just above a glut of lieutenants and midshipmen. Three years later, Wilkes was a midshipman, viewed by most fellow officers as a bookworm short on sailing skill.

A tour at sea wore on Wilkes, who scorned both the ranks and officers—the latter prone, he said, to “debauchery and drunkenness.” Spending the next 13 years ashore, he mastered calibration of sextants and chronometers and developed ways to survey coastal waters and produce charts. After Wilkes surveyed Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay in 1833, the Navy assigned him to head the Department of Charts and Instruments in Washington, DC. To chart the Georges Bank off Newfoundland, Wilkes used shallow-draft ships. On that voyage, uncharacteristically, he developed a camaraderie with subordinates; all hands had a jolly time taking soundings. The trip produced excellent charts. Wilkes’s skills made him indispensable for the polar expedition, Catesby Jones felt, assigning him the first slot for a lieutenant.

The expedition ran afoul of Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson, who so pinched pennies that he opposed opening a naval academy. Squabbles with Dickerson gave Jones an ulcer. That November he began coughing up blood and resigned his command. To work around Dickerson, a frustrated President Martin Van Buren moved the expedition proposal to the desk of Secretary of War Joel Poinsett. Finding that Navy captains afraid for their reputations were declining to lead the squadron, Poinsett put Wilkes in charge. Navy brass and members of Congress roared in protest. Van Buren assured Wilkes of his full support.

The expeditionary squadron comprised the 780-ton USS Vincennes and the 650-ton Peacock, both sloops of war, 230-ton brigantine Porpoise, and 468-ton supply ship Relief. For shallow-draft work around reefs, Wilkes added the 70-foot schooners Flying Fish and Sea Gull. Lieutenants would command every vessel. Wilkes, who chose Vincennes as his flagship, sought captaincies for himself and his second in command, William Hudson. The Navy refused; both would sail as lieutenants. On August 18, 1838, the little fleet weighed anchor at Hampton Roads, Virginia. The ships’ rosters of nearly 500 included U.S. marines, naturalists, botanists, a mineralogist, a taxidermist, a philologist—and Wilkes’s nephew, Wilkes Henry, 19, a midshipman.

The expedition had a three-year schedule, based on the duration of crewmen’s enlistments, and ambitious orders. The first task was to cross the Atlantic to the Madeira Islands to investigate shoals there, then sail west to chart the mouth of Patagonia’s Rio Negro. From Patagonia the ships were to attempt to sail to the South Pole—first a try from Tierra del Fuego, at South America’s southern tip, and, if necessary, from Australia. Next the squadron would survey the Navigator, Society, Samoan, and Fiji island groups, en route collecting specimens of flora and fauna—and while in Fiji revenge the whaling vessel Charles Daggett. Besides charting the Hawaiian Islands, the squadron was to take gravity readings, then chart the Pacific Northwest coast, in particular the Columbia River and San Francisco Bay. The final stage was to sail west and circumnavigate the globe, ending the voyage in New York City.

The expedition’s officer corps split between Catesby men and Wilkes men. The factions divided over seafaring skills, which the Wilkes bunch lacked, and discipline, of which Wilkes was very fond. From the onset, Catesbyites took umbrage at him for doubling to 24 the number of lashes laid on miscreant sailors, a sentence exacted on 25 occasions in the course of the trip.

At the Madeira Islands, said to perch amid shoals, the squadron found none. The squadron sailed for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Relief lagged, causing Wilkes to fear the stores ship would be a drag on the expedition. Some of the ships reached Rio on November 21, 1838. Relief anchored November 27. Rio was home base for the U.S. Navy Brazilian Squadron, one of several such forces protecting American shipping. During refitting in Rio, Brazilian Squadron commander Commodore John Nicholson, acknowledging Wilkes’s rank, addressed him as “Mister,” as was proper for a lieutenant. At this, Wilkes threw a tantrum and developed crippling headaches. Afterwards, Nicholson wrote to Wilkes, “To call you a Captain or a Commander would not make you one.” Reading the message, Wilkes passed out. Delayed by his condition, a possible nervous breakdown, the expedition left Rio on January 6, 1839. Noting the imminence of storm season, more experienced officers suggested Wilkes forgo surveying the Rio Negro. He ignored that advice, charting the Argentine river before continuing south amid gales and mountainous waves. On February 19, the squadron arrived in Orange Bay, Tierra del Fuego, the tip of Argentina. Wilkes had the larger ships’ crews do repair work and sent Porpoise and Flying Fish 500 miles south into iceberg-laden waters. On March 22, the Flying Fish crew passed the southernmost recorded point—latitude 70 degrees 14 minutes south—and, amid harsh weather, turned back toward Orange Bay, unaware that the schooner was only 114 miles from the Antarctic continent. Flotilla again intact, Wilkes beat around Cape Horn for Valparaiso, Chile, 1,600 miles north. All vessels made it to the Chilean port except Sea Gull, assumed lost.

To make better speed, Wilkes decided to send the laggard Relief home, figuring to obtain supplies as he went. The squadron’s most experienced officers, who had wanted to skip the Rio Negro survey, suggested Sea Gull and crew perished because Wilkes had been late to Tierra del Fuego. Wilkes sent Relief, packed with malcontents, out of Valparaiso on July 15, 1839. Aboard Vincennes, Wilkes assembled his entire command. Breaking with tradition, he declared himself by his own authority not only a captain of the U.S. Navy, but the squadron’s commodore.

From Valparaiso, the squadron sailed northwest 4,200 miles to the Tuamotu Atolls and Tahiti, where landfall began a pattern. Wilkes would send Hudson ashore with armed men to hold back hostile natives while survey crews charted surrounding waters. Mollusk expert Joseph Courthouy collected coral and shell specimens. Naturalist Charles Pickering and linguist Horatio Hale made notes on inhabitants’ daily life, language, and culture. The flotilla charted 17 of the Tuamotu atolls before reaching Tahiti, where Wilkes, on grounds of preserving discipline, barred officers from socializing with islanders off duty; morale curdled. On October 10, 1839, the expedition sailed from Tahiti to Pago Pago, Samoa, 1,500 miles west. The Americans found Samoans willing to provide food, canoes, and harbor pilots. However, departing Pago Pago Wilkes again floundered. Vessels at that harbor’s narrow mouth encounter swells large enough to drive them onto nearby rocks. Steering Peacock, Hudson needed four hours to get his ship to sea. Vincennes, with Wilkes commanding, had a local pilot whose advice, in fluent English, the self-appointed commodore ignored. Shifts in wind and wave suddenly sent the flagship at the rocks. Wilkes, stunned, stood at the rail, face in hands. The pilot leaped to action, barking orders to crewmen who were able to right Vincennes and reach open water.

Within days the squadron was sailing for the port of Apia, on the Samoan island of Upolu, where, combining new and existing data, Hale discovered that South Pacific trade winds varied seasonally. He concluded that Polynesians, who populated most of the region, had originated in Samoa. At Apia the squadron got word that two French ships had passed through Samoa under Captain Dumont d’Uville en route for the South Pole. Agitated, Wilkes made a beeline for Sydney, Australia, 2,700 miles southwest, to ready his fleet for an Antarctic dash. Peacock was structurally unsound but necessary to the foray. News two British ships also were en route to the pole added to Wilkes’s sense of urgency. Intership communications being limited, he issued orders in port. Departing for the pole, the fleet would split in two. Vincennes and Porpoise would sail together. Hudson, aboard the compromised Peacock, would lead Flying Fish. After the pole attempt, Hudson was to return to Sydney get Peacock into trim. The flotilla was to reconstitute at Bay of Islands, New Zealand. On December 26, 1839, the ships set out southbound from Sydney. Wilkes wrote in his diary that after dodging icebergs and heavy fog, on January 16, 1840, crewmen aboard Vincennes and two of the other vessels spotted what they believed to be land. Wilkes claimed on behalf of the squadron the discovery of the continent of Antarctica that day. The next day, Vincennes was almost trapped by ice sheets but was able to extricate itself. The same day, men aboard Peacock observed an orca attack a whale of another species “in the same way as dogs bait a bull, and worry him to death.”

On January 23, Wilkes reported seeing open water to the south, with land observed “at either hand, both to the eastward and westward.” Venturing about 15 miles into this bay, Wilkes’s crew was crestfallen to find that the way was blocked by “close packing of the icebergs.” Unable to go any further south into what Wilkes dubbed “Disappointment Bay,” the squadron turned around and headed westward, sailing 800 miles along the shore of what the commander deemed “Wilkes Land.” Ice was closing in on the fleet on February 21 when, spotting Peacock, Wilkes signaled for Hudson to come aboard. Wilkes told Hudson to sail Peacock to Sydney; he would lead the rest to New Zealand.

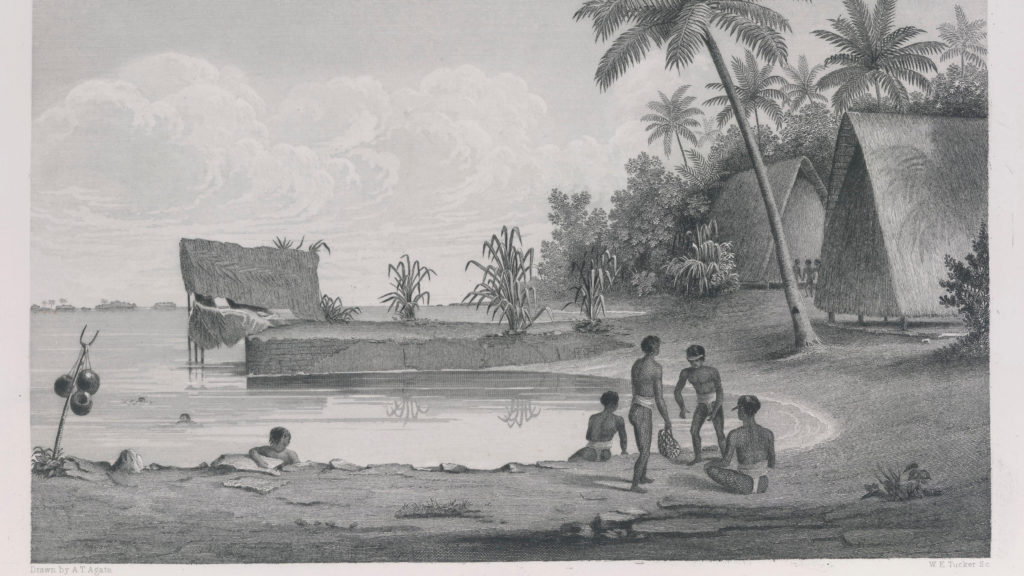

The rendezvous at Bay of Islands, 2,200 miles southeast of Sydney, came off, whereupon the squadron made for the Tonga Islands, some 1,500 miles northeast, then Fiji, 500 miles further. Without Relief as a larder, Wilkes had to buy food in New Zealand and stow it where he could. The squadron reached Fiji in mid-May 1840. Fearful of his men’s safety from heavy surf at the atoll’s entrance, Wilkes at first kept the ships circling as chart makers worked. The Americans learned that European beachcombers living among the Fijians were willing to act as guides, Wilkes began sending men ashore. He learned the whereabouts of Veidovi, or Vendovi, the Fijian chief and possible cannibal said to have savaged the whaler Charles Daggett. Peacock was near where Veidovi was reported to be; Wilkes ordered Hudson to capture the suspect. Hudson took other chiefs hostage, conveying to Veidovi that unless he surrendered his clansmen would die. Veidovi surrendered. Wilkes ordered him confined for transport to America. Relations between Fijians and Americans disintegrated. Warriors captured a surveying cutter. Wilkes burned their village. He announced that after a week of additional survey work the squadron would sail to Hawaii.

But Wilkes had not bought enough food. Stores were running short. On Malolo, 20 miles off the main island of Fiji, natives proposed to sell the Americans hogs. Lieutenant Joseph Underwood of Porpoise led a party that included Midshipman Wilkes Henry to parley with the Fijians. The deal was a ruse; warriors ambushed the sailors, killing Underwood and Henry. In retaliation, Wilkes attacked Malolo, killing more than 80 warriors, and forced survivors to supply the expedition with food and water. Blaming Underwood for getting his nephew killed, Wilkes had the dead man’s belongings auctioned, ignoring Underwood’s will and further alienating expedition officers.

From Fiji, the expedition sailed in August 1840 for the Hawaiian Islands, 3,200 miles northeast, to conduct surveys of the chain’s main islands. The voyage was at the three-year mark, with crewmen’s enlistments expiring. At Hawaii, Wilkes flogged more men and flogged them harder, whipping four Marines nearly to death to force their re-enlistment, a tactic he extended to the crew at large. He had three men flogged “round the fleet”—rowed ship to ship in a small boat, with whippings at every vessel until each penitent had had at least 110 lashes. Even so, the crew reveled in newspaper reports lauding them for discovering the South Pole.

To measure gravity on Hawaii, Wilkes forced sailors and Hawaiian laborers to drag a heavy metal pendulum up the 14,000-foot Mauna Loa volcano, hacking a path as they went. Upon completion of that ordeal the self-appointed commodore sent Peacock and Flying Fish, under Hudson, to chart the Gilbert Islands, 1,800 miles south. Geologist James Dana went along. In the Gilberts, Hudson heard that natives had massacred an American ship’s crew and passengers. He investigated. Residents seemed peaceful. He and his party were about to row to their ships when a man turned up missing. The landing party demanded his return. Islanders using swords mounted with sharks’ teeth and spears tipped with ray stingers drove the interlopers into the sea. The next day, Hudson shelled the island, then landed a force, which 700 islanders attacked. Sailors killed 12 warriors and torched two villages. The missing seaman never was found.

At Hawaii, Hudson learned Wilkes had departed for the Pacific Northwest, and, after a layover, he followed. Based on his observations in the Gilberts, geologist Dana described two ground-breaking theories; how decaying volcanoes form atolls and how island chains take shape, older, more eroded outcroppings at one end and younger islands at the other. Dana’s observations underpinned later development of the concepts of a moveable Pacific Plate and “hot spots”—stationary heat sources in the earth’s interior.

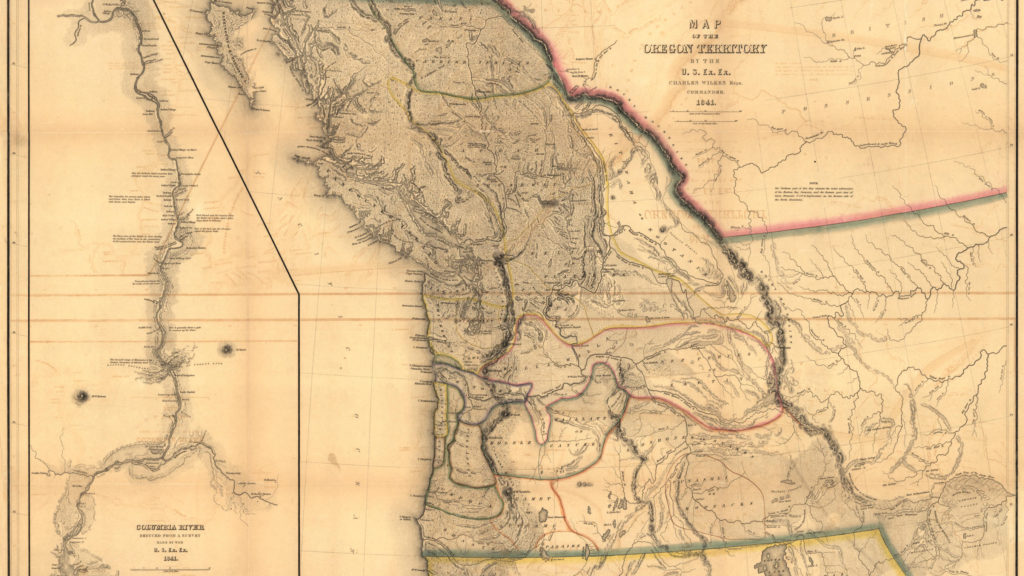

Wilkes arrived at the Pacific Northwest coast and the mouth of the Columbia River on April 28, 1841, sailing north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and undertaking to chart Puget Sound. Hudson reached the Columbia July 17 and began a survey. The shallower-draft Flying Fish was the logical choice for the task, but Hudson sailed the much larger Peacock into the waves. Peacock grounded irretrievably on a sandbar. Indians in canoes rescued the crew and the expedition’s records. Wilkes returned and surveyed the Columbia from its mouth to 100 miles upriver at Fort Vancouver.

Wilkes’s orders now called for charting San Francisco Bay, then Mexican territory. He sent a party on foot in that direction while leading the squadron south along the coast, surveying the California shoreline and planning to rendezvous with the overland party at San Francisco Bay to chart that body of water, which he did. Per orders, Wilkes departed the West Coast on Halloween 1840, sailing west around South Asia and Africa for New York City, where the squadron docked June 10, 1842, having logged 87,000 miles, lost two ships, and had 28 crew members die. Soon after arriving in New York, the imprisoned Fijian Veidovi died; his preserved skull was sent to the Smithsonian Institution, which also took delivery of the expedition’s 60,000-plus plant and bird specimens.

The Navy court-martialed Wilkes for losing Peacock and for abusing his men. Convicted of administering illegal punishment, the discoverer of Antarctica was acquitted on all other charges. Wilkes remained in uniform, spending 1843-61 producing charts for and reports on the locales the expedition had visited. Besides claiming Antarctica and mapping Wilkes Land, Wilkes had explored 280 Pacific islands and 800 miles of the Oregon and California coast. During the Civil War, Wilkes again made news. As captain of USS San Jacinto, he boarded a British vessel to seize Confederate diplomats, nearly sparking war with Britain. Transferred to the James River Fleet, he retired as a rear admiral.

Congress never followed up on Wilkes’discovery and charting of Wilkes Land’s two million square mile mass. In 1841, based on its explorers’ claim, Britain annexed the polar region, in 1933 titling it to Australia as part of the Australian Antarctica Territory.