Coalition of slaveholders and conservative abolitionists offered black Americans a land of ‘liberty’

FEAR OF SLAVE REVOLTS and assumptions about freed blacks’ ability to function in a white-dominated society led opposing factions in the United States to establish an informal colony in West Africa soon after the War of 1812. This joint effort between the federal government and an unlikely coalition of conservative abolitionists and slaveholders originated as a way to exile potentially troublesome freed blacks from the antebellum South and to offer free blacks in the North an out from institutional racism. This paternalistic, ham-handed undertaking acquired a naive back-to-Africa aspect before leading to the creation in 1847 of the nation of Liberia.

In the summer of 1800, a charismatic enslaved blacksmith named Gabriel, also known as Gabriel Prosser, conceived and organized a revolt by bondsmen in Henrico County, north of Richmond. Gabriel’s plan, formed with help from freed blacks, was to have slaves in the region rise Sunday night, August 31, 1800, to infiltrate and torch Richmond, the state capital, then home to 6,000. Gabriel and co-conspirators planned amid the resulting uproar to kidnap Governor James Monroe and hold him hostage as a bargaining chip for their freedom. On Saturday night, August 30, rain was starting to fall as a slave named Pharaoh slipped into Richmond and warned authorities of the imminent uprising. The rain worsened, causing floods that kept conspirators in place, unaware that Pharaoh had betrayed them.

As soon as the rains let up, Monroe had patrols round up plotters; the governor had the courts prosecute 70 slaves as co-conspirators. During the trials, begun immediately, reports that freed blacks had assisted in plotting the rebellion spread nationwide, as did newspaper coverage of the ensuing executions. Monroe hanged 26 men; Gabriel swung from the gibbet on October 10. The governor pardoned the remaining 13 plotters.

In 1800, Virginia was home to 20,493 freed blacks. Under southern state laws that varied around the region, freed blacks had no citizenship, could not vote, were subject to nighttime curfews and search and seizure without due process, and were banned from trades like interstate transport and the maritime, where they might learn about events in the outside world, medicine, and certain other occupations. The idea that any or all such individuals might assist the state’s 346,671 slaves in rising against Virginia’s 517,653 white residents shook the state to its core. That worry came to permeate the South.

In 1807, Britain outlawed the slave trade. Royal Navy ships began stopping slave ships and liberating those held aboard. In 1808, Britain resettled liberated individuals at Freetown, the only community in the royal colony of Sierra Leone, on the West African coast. In 1808, the United States outlawed importation of slaves.

In 1815, Paul Cuffee was the wealthiest freedman in the United States. Son of a Native American mother and a former slave kidnapped from Africa, Cuffee grew up on Martha’s Vineyard, a Massachusetts island and whaling industry hub. As a young man Cuffee went whaling, then built a coastal cargo vessel, in time acquiring a fleet busy at trans-Atlantic shipping. He thought freed blacks could avoid New World bias only by creating their own society on their own land. In 1815, Cuffee laid out $4,000 to transport 38 black Nova Scotians and African-Americans to Sierra Leone, along with farm tools and sawmill components. Arriving with the immigrants at Freetown in February 1816, Cuffee paid each enough in advance to buy a year’s worth of provisions. He remained in Sierra Leone for months assisting the colonists before departing for home. As Cuffee was sailing to New York in late 1816, former Virginia governor Monroe was winning the American presidency in a landslide.

Cuffee had decided freed African-Americans ought to emigrate to Africa. He petitioned Congress for funding to transport black colonists. Congress said no, but Cuffee’s appeal moved white Presbyterian minister Robert Finley, dean of Brick Academy in Basking Ridge, New Jersey. Finley’s prestigious private school educated the sons of the wealthy from as far away as Georgia, giving him clout with the American establishment that he used to urge the United States to establish a colony in Africa.

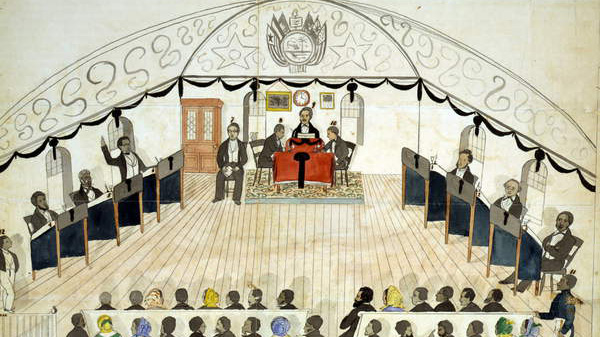

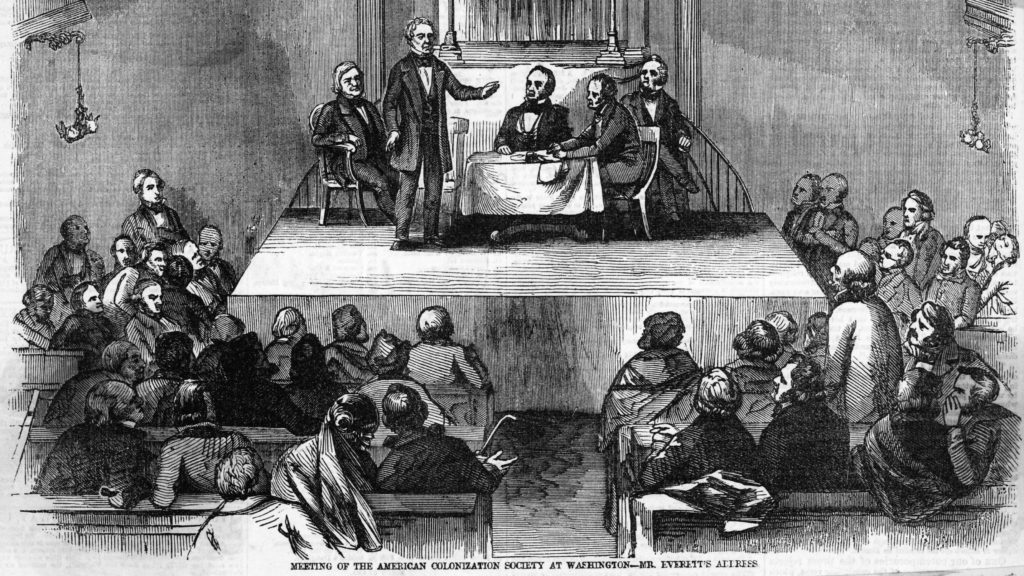

Finley convened a meeting at the Davis Hotel in Washington, DC, on December 21, 1816, at which he formed the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Color in the United States. In attendance were slave holders, philanthropists, clergymen, and abolitionists. Participants also included luminaries Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, Francis Scott Key, Daniel Webster, and Associate Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington, a nephew of George Washington—all eclipsed by the enthusiastic presence of President-elect Monroe. In declining health from working in the tropics, Cuffee was too sick to be on hand; within six months, he and Finley were dead.

Meeting goers elected Washington to head what became known as the American Colonization Society. For three years the jurist guided the society’s efforts to promote itself and to raise money to buy and free slaves and send them to Africa. Simultaneously white southerners were undertaking to rid themselves of freed blacks as potential firebrands. Even most abolitionists of this period believed black people to be inferior to and unable to coexist with whites.

Freedmen wanting to emigrate under the Society’s auspices had to apply and present letters of recommendation. Contributions bought scant slaves their freedom for emigration to Africa; only six between 1820 and 1825. In their wills, a few Southern planters offered their slaves freedom if they went to Africa. Many declined. As a man in Virginia explained, his wife and children were scattered across neighboring plantations; he could not leave them behind. Enslaved people also feared transport to Africa could get them killed by natives or disease, as well as sensing that to return to Africa was to accede to a second, no less just exile. In a will made out in 1832, Richard Brookhiser reports in a 2018 biography of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, Marshall offered long-time personal servant Robin his freedom and $100 to move to Liberia or $50 to leave Virginia. Robin, in his late 60s, chose to remain enslaved to Marshall’s daughter.

As president, Monroe wanted to enforce the American ban on importing slaves and stop smugglers from sneaking kidnapped Africans into the United States. To achieve these goals, he planned to establish a naval station off the African coast and base warships there to interdict slavers. But first Monroe wanted to work out how the U.S. Navy would handle slaves liberated at sea. He persuaded Congress in 1819 to declare that Africans the U.S. Navy seized from slavers at sea would stay in government custody pending their return to Africa. Hesitating on constitutional grounds to establish a formal colony, Monroe cut a deal with Bushrod Washington and the Colonization Society. If the society would obtain land in Africa, the United States would pay for travel to and resettlement in that territory not only of formerly enslaved persons in federal custody but also of freedmen wishing to relocate to Africa. Elite southerners embraced the President’s efforts. Touring the South in May 1819, Monroe heard hosts in Savannah, Georgia, cheer his declaration that “the wisest heads and the purest hearts” were planning the putative colony, hoping “to bring happiness to millions.” Congress authorized $100,000 for African colonization. Economic arguments for a colony ranged from establishing an extension of the South’s Cotton Kingdom to opening jobs for whites in the north by reducing the ranks of freedmen there. Southern desire to banish freedmen and Northern desire to have such a colony bring about the termination of slavery eclipsed economic arguments.

Participating blacks had to sign a covenant recognizing the powers of the white governor the Society chose, accepting the governor’s veto power over the assembly they would form for making local laws, and a ban on their return to the United States. The governor, who represented both the Society and the United States government, had control over land sales and selection of a high sheriff from among the black population to enforce the law. Colonists could vote, govern themselves, own land, and engage in business.

The Society asked agents in Sierra Leone to locate a suitable site. Once operatives reported finding a good location 130 miles down the coast from Freetown, Sierra Leone, the ship Elizabeth, carrying 38 prospective colonists sailed from New York on January 13, 1820. All were freedmen eager to start a colony that would act as a beacon for other African Americans; the federal government was covering their $33,000 in relocation costs. At Freetown, the immigrants learned that locals had refused to sell the parcel selected. Insisting on landing there anyway, they found the property malarial and lacking potable water. Within three weeks yellow fever had killed all but 16 new arrivals. Survivors huddled in Freetown awaiting help.

Monroe sent the schooner USS Alligator under Lieutenant Robert Stockton to Sierra Leone. Aboard was Colonization Society official Eli Ayers, assigned by Bushrod Washington to rescue the Elizabeth survivors and find a proper site for the colony. Alligator’s mission marked the start of Monroe’s African Squadron, assigned to suppress the slave trade and coordinate with British forces doing the same. The first stop was Freetown, Sierra Leone, where handouts from local Quakers were sustaining the Elizabeth survivors.

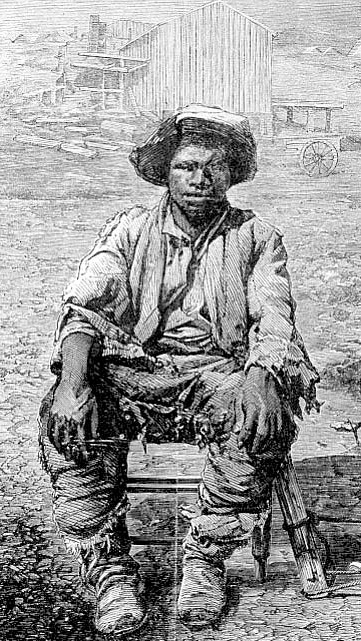

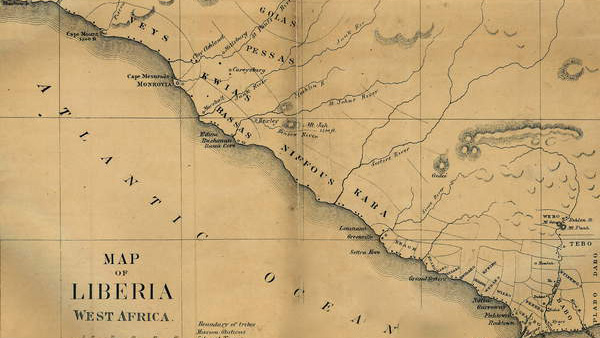

Sailing south along the coast, Ayers decided Cape Mesurado, 225 miles from Freetown, would make an ideal colony. The cape, which had a good harbor and good water, was ruled by Zolu Duma, also known as King Peter. His tribe, the Dei, was in the business of selling captured Africans to Spanish and Portuguese slavers, as were most tribes in the region. Ayers nonetheless drafted a treaty giving the Society, in exchange for $300 in goods, including rum and guns, title to a 36-mile strip of coast extending three miles inland. King Peter refused to sign—until Stockton put a pistol to the royal head. The colonists relocated to Cape Mesurado. With the Alligator’s gunners covering them, colonists, along with Ayers and immigrants from a second ship, built a village and earthen fort atop a hill. Stockton began interdicting human trafficking. Each living cargo he and his men freed, no matter what the captives’ origins—and they were from all over Africa—took up residence at Cape Mesurado. The incipient colony became a Babel of cultures, religions, and languages—with no interpreters. The land was hot, sandy, and dotted with mangrove swamps—besides yellow fever colonists feared malaria. Mosquitoes were ubiquitous. Of 4,571 emigrants settling in Cape Mesurado from 1820 to 1843, only 1,819 survived.

Stockton eventually had to return to the United States. Before leaving, he gave the colonists one of his ship’s cannons, which colonists emplaced on Fort Hill. In 1842 the American merchant ships Mary Carver and Edward Burley were trading in the area when tribes killed both vessels’ crews. King Peter decided the American colony was cutting into the slave trade. When newly appointed governor Jehudi Ashmun arrived with more colonists in June 1822, he found Dei tribesmen preparing to attack Cape Mesurado. The British at Sierra Leone offered help if the Americans would raise the Union Jack. Ashmun refused, though he had only 35 able-bodied men. Peter and his tribesmen attacked on December 1, 1822, killing the colony’s cannoneers. Settler Matilda Newport ran to Fort Hill and with her pipe set off the loaded weapon, killing the attackers and forcing King Peter to retreat.

President Monroe, intent on lending the colony military support, sent sloop of war Saratoga, under Commodore Matthew Perry, to Africa on June 5, 1823. Perry rendezvoused in the Cape Verde Islands, 350 miles off West Africa, with the enlarged Africa Squadron’s other three warships. Perry intended to use the Cape Verdes as a base for intercepting slave ships.

Perry’s ships anchored at Cape Mesurado on November 23, 1823, taking aboard Governor Ashmun and proceeding southeast. Five days later Perry and his marines landed at a village, Sinoe, whose chiefs the Americans questioned about the Edward Burley. The chiefs claimed Burley’s crew had attacked first, prompting a counterattack and the subsequent torturing to death of surviving Americans, a story that Perry accepted. He and Ashmun negotiated a treaty whereby the chiefs of Sinoe recognized Cape Mesurado’s sovereignty.

Perry continued southeast to Little Berebee, a Kru village linked to the Carver massacre. Perry landed on December 11 with 50 marines and 150 sailors to interview Kru king Ben Krako. Meeting Krako in a hut, Perry decided the ruler was lying about the massacre and said so. Krako tried to spear Perry, who toppled the African and dashed outside. Marines shot and bayoneted the king. As his men exchanged fire with natives, Perry searched the hut, finding the Carver company flag and bits of the missing schooner. He ordered Little Berebee burned. Kru fighters ambushed the landing party, drawing fire from the American ships. Perry sailed the coast, burning seven villages. Just before Christmas, after dropping Governor Ashmun at Cape Mesurado, Perry headed north to the Madeira Islands.

Perry’s flexing of American muscle, persuaded the powerful Kondo confederation, which controlled the most of the region’s interior, to recognize the American settlement at Cape Mesurado. Confederation chief Sao Boso informed Ashmun about trade routes for ivory, grain, and other goods from the north. The confederation agreed to accept the African-American settlement as regional overlord, entitled to levy taxes on the region’s tribes. Ashmun assigned the high sheriff to collect those taxes, in gold, with an armed escort. Control of the Kondo region vastly enlarged the colony, but Ashmun was not satisfied. He traveled upriver lobbying other chiefs to recognize Cape Mesurado’s sovereignty and bringing sections of the interior into the colony.

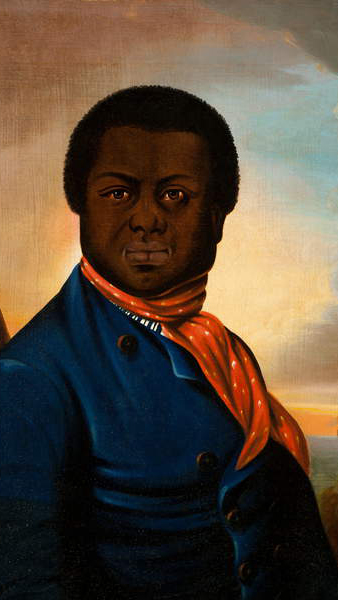

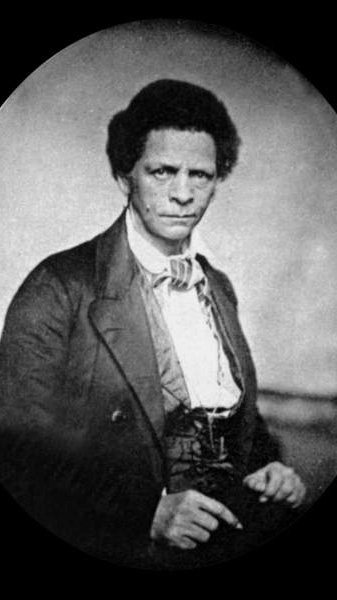

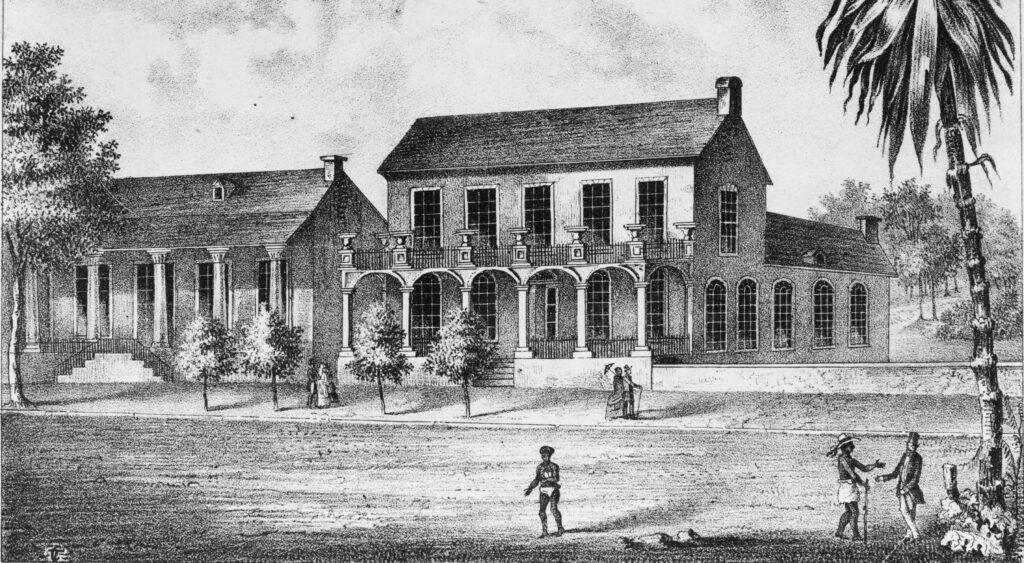

By 1824, colonists, now numbering 1,200, had tired of having a white governor, of that governor having veto power over the assembly, and of their dual allegiance to the Society and the United States. Ashmun worked with the assembly on a new constitution designating the colony Liberia, Latin for “land of the free,” and emulating the U.S. Constitution with a bicameral legislature and a supreme court. The Society still picked the governor, but colonists would elect his deputy and the high sheriff. In gratitude to President Monroe, the Cape Mesurado settlement renamed itself Monrovia. Most emigrants became farmers. A few acquired palm oil and coffee plantations. Nearly all males served in a militia raised to respond to threats from neighboring tribes or slavers. Residents’ letters to the United States convey a sense of mission. Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a freedman and barber from Virginia, sailed for Liberia in February 1829 with his mother and five siblings. In Monrovia, Roberts and two of his brothers began exporting palm products, camwood used for scented soaps, and ivory to the United States, meanwhile importing and selling American goods. Roberts was elected high sheriff. Peyton Skipworth wrote of his crops supplying local demands in Liberian towns and his pride to be serving in the Liberian militia. Former slave William Burke closed a letter, “The Lord has blessed me abundantly since my residence in Africa.”

The Colonization Society ruptured over the rise of abolitionism and Southern fear of slave revolt. Abolitionist David Walker in 1829 publicly denounced Society members as “fools,” citing the few emigrants and the millions of blacks in the United States. William Lloyd Garrison renounced his Society membership, proclaiming the only way to solve the slavery issue was “militant opposition” to racism. Southern members of the Society wearied of Northerners wanting to buy slaves freedom. Citing the 1831 episode in which Nat Turner led a slave revolt in Virginia, Southerners said money should go to ship “agitating” freedmen out of the South.

Andrew Jackson, elected president in 1832, thought colonization no way to solve the nation’s racial issues. America had two million slaves, 169,000 freedmen in the South, and 150,000 freedmen in the North—impossibly large numbers for Liberia to absorb. An 1833 audit showed that in 11 years the federal government had given the Colonization Society $264,710 on top of Monroe’s initial $100,000. In 1834, Jackson slashed federal contributions to Liberia except for a pittance paid because Liberia received individuals rescued by the African Squadron.

Jackson’s cuts squeezed the Colonization Society. Funding shifted to private sources, principally in the North. In 1834, the society was $45,645 in debt. The antislavery movement veered from colonization and toward abolition without expatriation. Rhetoric on both sides became heated, evaporating contributions and dues. When in 1838 the society reorganized under a board whose membership was based on regional contributions, control came into Northern hands. Wanting to manage relocation on their own terms, states started individual colonization societies. Entities in Pennsylvania and New York pooled funds to create a settlement at Bassa, east of Monrovia, in 1833, with Thomas Buchanan as governor. In 1834, a society in Maryland set up a settlement at Cape Palmas. Mississippi and Louisiana set up habitations around Sinoe in 1838. All these took root in the original 108-square-mile coastal strip obtained by treaty. These settlements came under attack by slave-taking tribes. Seeking relief, the towns at Bassa in 1838 asked Liberia to annex them. Bassa governor Buchanan was made governor of Liberia. More annexations occurred. Liberia declared itself a commonwealth. The Maryland colony held out, in 1841 declaring itself an independent state. That year Governor Buchanan, 33, died. His deputy, Joseph Roberts, the immigrant barber from Virginia, became Liberia’s first black governor. Roberts attempted to impose import duties on goods being brought in from Sierra Leone. Britain balked. Roberts asked for assistance from the United States. The administration of President John Tyler, unable to budge Britain and unwilling to claim Liberia as a colony, advised the Liberians to declare independence, a line also voiced by President James K. Polk and his administration.

In 1847, Liberia’s congress called for a referendum on independence among the 7,000 colonists who had come from America. Liberia’s 80,000 Africans of various tribes and 15,000 residents rescued from slavers could not vote. The measure to become a sovereign nation passed overwhelmingly. The Polk administration assisted Roberts in organizing a professional bureaucracy. On July 26, 1847, Roberts declared Liberia an independent nation, announcing that a presidential election would take place October 5. Roberts won that race.

Carved from the African jungle by American freedmen and American gunboat diplomacy, the nation of Liberia claimed 300 miles of coastline and 13,000 square miles total area through treaties with interior tribes. The country was exporting $500,000 yearly in coffee, palm oils, ivory, and exotic lumber. But injustices abounded. Indigenous people had no protections under the constitution; Liberian soldiers often hounded them off their land. African Americans hoodwinked indigenous men into signing bondsmen agreements and shipped them off as cheap labor to nearby Spanish and Portuguese colonies. On Liberian plantations, many rescued slaves—African Americans called them “Congos”—were no better than indentured field hands. Shortly after Roberts took his oath of office on January 3, 1848, Liberia received a grave blow: to coddle southern senators furious at having to welcome a black ambassador, the Polk administration was withdrawing recognition. Roberts sailed for Europe. He met with Queen Victoria, leading to Britain’s 1848 recognition of Liberia. France’s recognition followed. Portugal, Brazil, and the Austrian Empire chimed in. In 1857, after Liberia helped inhabitants of the recalcitrant enclave founded by Marylanders quell an uprising by indigenous residents, the Republic of Maryland joined Liberia. By 1859, most of Europe officially had acknowledged the new country’s sovereignty. On February 5, 1862, under President Abraham Lincoln, the United States of America recognized the nation of Liberia.