Spunky singer-songwriter made it big with Western sound

ONE SPRING DAY IN in 1940, Cindy Walker, 22, was riding with parents Aubrey and Oree along Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, California. The Walkers, originally from around Waco, Texas, but living in Phoenix, Arizona, were visiting the City of the Angels because Aubrey, a cotton broker, had business there. Cindy, a singer and songwriter, was trying to break into the show business in LA. The Walkers were in the 9000 block of Sunset when Cindy shouted, “Stop!” From the sedan’s back seat, she had seen the name “Crosby.” Surely that was the building where movie and singing star Bing Crosby worked. Aubrey Walker, who thought his daughter had gone “squirrelly,” pulled over between Doheny Drive and Hammond Street. In a flash Cindy, briefcase in hand, was out of the car and running for the entrance to 9023. A receptionist confirmed that she was in the offices of Bing Crosby Enterprises. The star was out, but his older brother and publicity director Laurence “Larry” Crosby was in.

Did the visitor have an appointment?

“Just tell him somebody from Texas is here to see him,” Cindy Walker said.

The receptionist passed along that message. Larry Crosby, curiosity piqued, invited Walker to chat. She explained that she was a songwriter with material his brother ought to hear. Larry Crosby agreed to listen to a tune. The office had a piano. Excusing herself, Walker ran to the car and begged her mother to accompany her while she sang a song Bing Crosby might hear. A flustered Oree agreed, provided Cindy did not say she was her mom. With Oree at the keys, Cindy sang “Lone Star Trail,” about a cowboy on a cattle drive, in her silky, warm voice.

Her one-man audience said she should come to Paramount Studios the next day and meet his brother. Walker could not get her mother to reprise her performance. “She said she was embarrassed to death. I took my little guitar,” Walker recalled many years later. “Bing was sitting there in his chair at Paramount Studios, and a publisher from New York was sitting with him. The publisher said ‘Can I listen too?’ And so we all went up to Bing’s dressing room. I sang ‘Lone Star Trail,’ and he said, `I like it. I’ll do it.’ Then the publisher said, `I like it and I’ll publish it.’

“I said, `Shucks, there ain’t nothing to this.’”

The house of American popular song has many mansions of style and genre. Between the 1920s and the digital revolution, generations

of tunesmiths learned their craft listening to and writing for the radio. One was Texas-born Cindy Walker. Through radio a fan of Cole Porter and other stalwarts of Tin Pan Alley, Walker wrote a remarkable string of hits in the country vein. As her song-plugging debut in 1940 shows, she worked with a broad spectrum of personalities and forms.

When he met Walker, the singer and actor Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby had been America’s first and leading multimedia star since 1931. Now “der Bingle,” as he was nicknamed, was working up an album—record companies sold their 78-rpm wares in protective sleeves packaged like pages in a photo album—entitled Under Western Skies. “Lone Star Trail” fit the bill. His companion that day, lyricist-publisher Lester Santly, famed for the words to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and other hits, agreed. Crosby, whose own career had begun through a series of similarly random occurrences, arranged for Walker to record a demo for Decca Records executive Dave Kapp. Kapp offered Walker a recording contract. She accepted and never looked back, soon after making a singing appearance in the Gene Autry film Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride. “I’m a natural-born plugger,” Cindy Walker liked to say. “I’m not intimidated by anyone.”

Cindy Walker was born into a multigenerational musical family. Maternal grandfather Franklin Eiland (1860-1909) was a prolific hymn writer, music teacher, and composer who helped found a music publishing company in Waco, Texas, in the 1890s. In 1896 Eiland, twice-widowed, married his third wife, Minnie Valentine of McLennan County, Texas. Daughter Mary Ella Oree Eiland, known as “Oree,” was born to this piano-playing couple in 1899. Oree inherited her father’s musical bent, growing into an accomplished pianist taught at home by her folks. As a teenager, Oree married cotton broker Aubrey Walker. The couple had two children, Aubrey Jr., born in 1915, and in 1918

Lucille, always known as “Cindy.” Both children were born on their paternal grandparents’ farm about three miles north of tiny Mart, Texas, in McLennon County. The young family usually lived in and around nearby Waco, frequently moving to accommodate Aubrey’s work and traveling to surrounding states.

Cindy’s father’s side showed little musical talent but plenty of encouragement, especially from grandfather Thomas Q. (T.Q.) Walker, who lived with wife Ona on a farm 18 miles east of Waco. T.Q. and Ona grew cotton and wheat, often hosting Cindy and her brother, whose play included riding with friends at adjoining ranches. “Those were my people that I knew the best,” Walker said later. Grandfather Walker always encouraged her love of music and for many years was a lonely voice taking her songwriting seriously. “Papa” Walker, her biggest fan, listened to her tunes and bought her first guitar, a Martin, at a pawn shop.

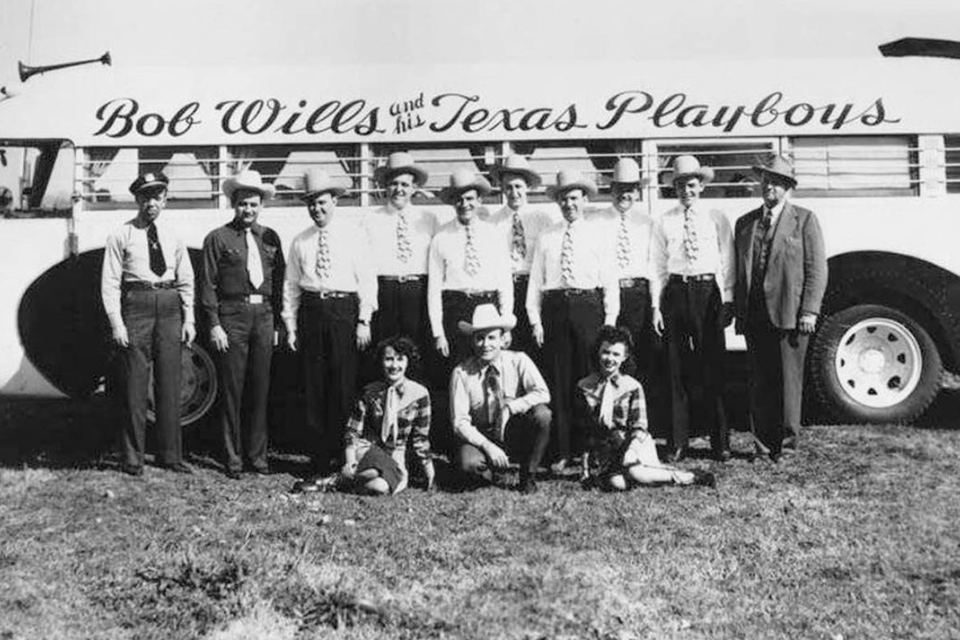

Cindy responded to inspiration as she found it. At her grandparents’, she studied news clippings her grandmother had collected about Oklahoma in the Dust Bowl years. Moved by stories of livestock dying of thirst and dust storms carrying away lives, she wrote, “Sand blowing, I just can’t breath in this air/I thought it would soon be clear and fair/but dust storms played hell with land and folks as well, got to be moving somewhere/Hate to leave the old ranch so bare, I’ve got to be moving somewhere…” “That’s a great song,” her grandfather said. “No matter who wrote it.” A decade later, Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys made “Dusty Skies” a hit, later covered by many others. When she wrote it, Cindy Walker was 12.

Wherever the Walkers were, there was music, from the radio or her mother’s piano, Cindy never took a music lesson, but she learned to form basic chords on piano and guitar and to pick out tunes by ear on the piano. She began performing as a child and at 10 spent a summer traveling with a vaudeville troupe, Toyland Revue, as a singer and dancer. By her late teens, she was a veteran of many local and Waco-area shows and venues. When the Dallas Morning News ballyhooed in April 1936 that the Fort Worth Frontier Centennial needed “1,000 girls,” Cindy, 18, read the fine print advertising for “Show girls, dancers, male dancers and singers for Billy Rose’s JUMBO production at the Fort Worth Frontier Centennial. Girls of 20 or younger—or look that.” The Centennial was Fort Worth’s answer to a similar blowout by Dallas. Across 162 acres, the premises included a Frontier Village replicating a 19th-century hamlet. New York showman Billy Rose was making $1,000 a day running the extravaganza, whose most popular element was Casa Manana, the “House of Tomorrow.” Seating 4,000 facing a revolving stage, Casa Manana was the centerpiece of a dinner theater review featuring a chorus and dance troupe. Cindy’s audition got her into the singing and dancing chorus. While working, she wrote a song. “I talked to Billy Rose and told him I was the best dancer in Texas and got Papa to drive me to Fort Worth for the audition,” Walker told an interviewer. “I was hired right away. I had my guitar with me, and that’s when I wrote ‘Casa de Manana.’ Paul Whiteman heard it and said, `That’s the song I’ve been looking for to open my shows with.’” Whiteman, a popular bandleader who billed himself as the King of Jazz, adopted “Casa de Manana” as his radio theme song. Walker, in love with music and performance, set her mind to songwriting.

Hurriedly wed young and as hurriedly divorced—in later life she often denied ever being married—Cindy was 22 and living with her folks when she buttonholed the Crosby brothers. In light of their girl’s new recording contract, the Walkers moved to Hollywood. Aubrey counseled his daughter to treat songwriting as a business, read contracts with care, and always be pitching songs. Family support, including room and board, let Walker focus on developing her career in an era when it was unusual for women from her station to work.

Walker had a gift for matching songs to singers, as in her work with Wills. Originally a traditional Texas fiddler, he had hit big with his

“western swing” band, The Texas Playboys, modeled on outfits led by Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Tommy Dorsey, with fiddles and pedal steel and standard guitars augmenting the horns, woodwinds, and drums. In 1940 Tulsa, Oklahoma-based Wills released “New San Antonio Rose,” which went gold and made him nationwide star. Within the year Crosby had covered the tune, further integrating Wills into the scene. Fresh from her success with der Bingle, Walker had several songs she thought would appeal to Wills when she spotted the Playboys’ bus in LA. The band was in town to film their cinematic debut, Go West Young Lady. Working the phone book, Walker ran down the hotel where the band was staying. Wills saw her and began a fruitful collaboration beginning in 1941 with an extended play disc of Walker’s “Bluebonnet Lane,” “Cherokee Maiden,” “It’s All Your Fault,” and “Dusty Skies.” In 1942 Columbia Pictures contracted with Walker to write 39 songs for eight Wills movies. In time, Walker wrote more than 50 songs for Wills. Bands still perform many of them.

Walker’s recording contract with Decca interested her less than did writing and pitching and selling songs. Her one Decca release, 1944’s “When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold Again,” and “Pins and Needles,” both written by Gene Sullivan and Wylie Walker, reached No. 5 on that year’s country chart. During the 1940s, Walker appeared in a few movies and “soundies”—three-minute films, precursors to music videos, that movie theaters ran between double features. By 1947 she had given up performing and recording except to make demos with which to pitch songs.

When not working from her reading and other sources, Walker sometimes took on someone else’s idea. In 1947, working with Wills and his Playboys on movie tunes, she fielded a call from vocalist Tommy Duncan, who had dreamed up a title: “Watching the Bubbles in My Beer.” Could she do work with that? “I said, ‘You’re kidding,’” Walker said. “But I could tell by the silence on the other end of the line that he wasn’t.” Duncan recovered and described a man in a bar staring at his drink and musing about a lost love. Wills and his band had a hit that year with “Bubbles in My Beer,” credited to Walker, Tommy Duncan, and Bob Wills.

Assignments sometimes set Walker to studying. Broadcast Music Inc. head Edgar J. Burton asked her for a country number about Canada, whose western ranchlands are the equal of any below the American border. Knowing nothing of Canada, Walker parked herself in a library. She learned how the plains end at the Rocky Mountains, where in Alberta fields of yellow poppies surround glacially fed Lake Louise. That image led to “Blue Canadian Rockies,” an international hit in 1950 for singing cowboy Gene Autry and later recorded successfully by Jim Reeves, Slim Whitman, Hank Snow, and The Byrds.

After Aubrey Walker died in 1948, Cindy and Oree remained in Los Angeles, but in 1954 they returned to Texas, landing in Mexia (muh HAY uh), about 30 miles east of Waco, near brother Aubrey and his family. Walker spent the rest of her life in Mexia, rising daily at 5 a.m., brewing strong coffee that she drank black, and heading upstairs to her studio to write on a manual typewriter decorated with pink flowers. She worked alone, developing melody and lyrics together. Oree helped with arrangements and played piano on demos.

In the 1950s Cindy’s reputation as a country music writer solidified, and she had some of her biggest successes. Every October, she and Oree would board a train for the eight-hour ride to Nashville, where through April they rented an apartment and a piano, hosting a musical open house for singers and musicians who came for home-cooked meals and to hear and try out songs. Many a Nashville cat visited.

Walker’s best-known song of that period shows the almost alchemical way in which a lyric and melody take form. In 1955, about to leave Nashville after an industry event, Walker spontaneously called on Steve Sholes, head of RCA’s country music division. Singer Eddy Arnold was there. Arnold pitched Walker a title—“You Don’t Know Me”—in the voice of a shy fellow pining for a woman. Walker shrugged but said she would “let it cook.”

Back in Mexia, Walker went weeks without inspiration until in her head she heard, “You give your hand to me, and then you say hello/And I can hardly speak, my heart is beating so/And anyone can tell, you think you know me well/but you don’t know me.”

“The song practically wrote itself,” Walker said. But not really. She had an appealing opening verse and a melody, but no ending. More weeks passed. Walker noodled on guitar and piano, drafting and rejecting couplets. Nothing came until, again from the songosphere, emerged “…you give your hand to me/and then you say goodbye.” She transcribed the lines and in haste telephoned Arnold. “I says, `Hey Eddy, I’ve got something I want you to hear,” she later told interviewers. “And so I started singing it, and he had forgot all about it. He forgot all about the title. And he said, `That’s a wonderful song.’” Three weeks later, the Tennessean recorded “You Don’t Know Me.” In succeeding decades, the song became a standard, recorded by artists from Ray Charles to Willie Nelson.