As Lieutenant Colonel James R. Brickel rolled his RF-101C Voodoo into a photo run, he became the target for what could easily have been the most anti-aircraft fire ever aimed at a single plane. The operations officer of the 20th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (TRS) based at Udorn, Thailand, Brickel had volunteered for a mission to take poststrike photographs of the Thai Nguyen iron and steel plant, 30 miles north of Hanoi. In early March 1967, as part of Operation Rolling Thunder, Washington policymakers—after almost three years of official vacillation—finally approved an airstrike against Thai Nguyen, which had earlier been classified as one of the most important strategic targets in North Vietnam. By this time, however, the North Vietnamese had managed to saturate the site with 37mm, 57mm and radar-controlled 85mm anti-aircraft guns. The plant was also within a 60-mile envelope containing numerous SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites and approximately 100 MiG-17 and MiG-21 fighters.

The aging RF-101Cs of the 20th TRS, which had been scheduled for replacement with McDonnell RF-4Cs, were highly vulnerable to the defenses massed around Thai Nguyen, and Brickel knew it. But on that day—March 10, 1967—the choices were limited; someone had to get photos for a bomb damage assessment.

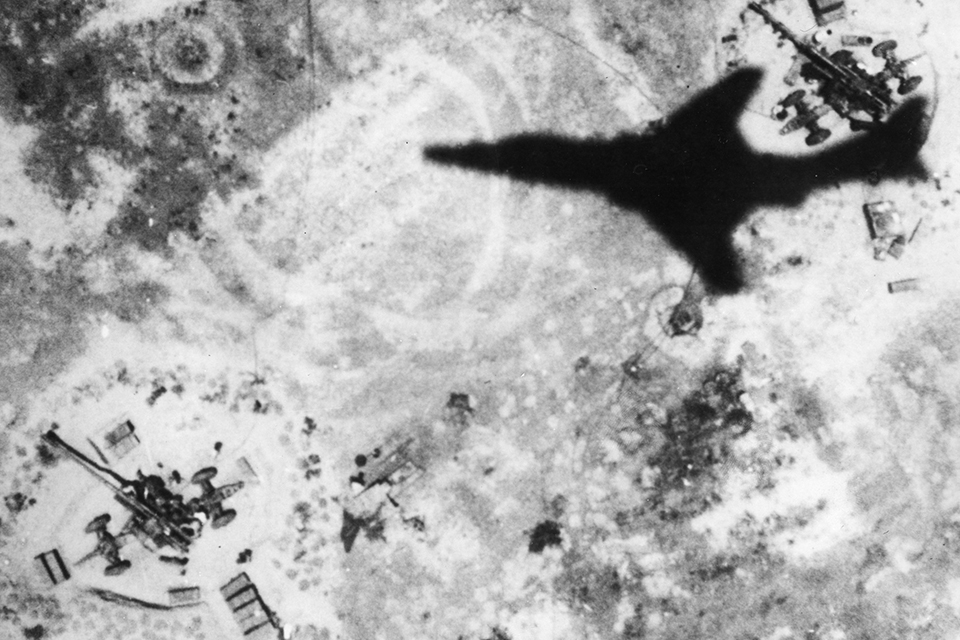

Due to the strike carried out earlier in the day, defenses near the plant were on full alert, and as Brickel’s aircraft approached, every enemy gun opened up. One minute away from the target an 85mm flak shell burst almost directly underneath the left side of his jet. Warning lights flashed on the instrument panel, oil pressure on the left engine fell to zero, hydraulic pressure to the flight controls bled off, the left aileron was holed and the cockpit began to fill with smoke. To make matters worse, the Voodoo’s airspeed had slowed by 50 knots, giving North Vietnamese gunners an easier target. But Brickel knew he couldn’t afford to abort the mission as long he could keep his plane flying. Fighting the controls, he rolled the cameras and held his course over the plant. Miraculously, he emerged from the storm of tracer fire and managed to coax his seriously damaged RF-101 back to a safe landing at Udorn, where he delivered the exposed film. Later, during a ceremony in which Brickel was awarded the Air Force Cross, General William W. Momyer, commander of the Seventh Air Force, referred to his performance over Thai Nguyen as “a superb display of guts.”

The origins of the F-101 actually had little to do with the jobs for which it was used over its long career with the U.S. Air Force, Air National Guard and Canadian Armed Forces. Neither tactical reconnaissance nor all-weather interception had been a factor in early 1946 when the newly formed Strategic Air Command solicited proposals for a jet-propelled “strategic penetration fighter.” SAC’s chief criteria at the time had been sufficient range to accompany its bombers (Boeing B-29s and the soon to fly Convair B-36s) all the way to their targets, and adequate speed and firepower to deal with enemy interceptors. Four sweptwing designs were ultimately approved for prototype development: the McDonnell XF-88 Voodoo, Lockheed XF-90 (not named), Republic XF-91 Thunderceptor and North American YF-93A (a development of the F-86), all of which flew between 1948 and 1950. When a fly-off was held in the summer of 1950, McDonnell’s XF-88A, an improvement over its 1948 prototype, emerged as the winner of the penetration fighter competition. McDonnell’s success was momentary, however; the Air Force, motivated by unexpected budget cuts, abruptly canceled the XF-88A program and made the decision to use Republic F-84E Thunderjets as interim bomber escorts.

Combat experience in Korea soon revealed that the straight-wing F-84s were not suited to the air-to-air role, and the North American F-86 Sabrejet clearly lacked the range to escort bombers to long-range targets. Something better was needed, so SAC—determined to protect its emerging fleet of B-36s—issued new requirements for a long-range fighter in January 1951, this time adding specifications for parallel development of a photoreconnaissance version of the new type. Lockheed, North American, Republic and McDonnell all submitted new proposals, joined by a bid from Northrop for a long-range version of its F-89 Scorpion.

In May 1951, the Air Force announced that McDonnell’s entry, basically a scaled-up XF-88A upgraded with more powerful Allison J35-A-23 (later J71) engines, was the winning bidder. But before construction was authorized, the Air Force specified major changes aimed at improving overall range and performance, the most significant being the substitution of Pratt & Whitney J57-P-13 power plants (15,000 pounds static thrust in afterburner), which required enlarging and lengthening the fuselage to carry more fuel and house bigger engines plus extensively revising the air intakes and related engine ducting. When the McDonnell team led by Edward M. Flesh completed the final design in late 1951, the Voodoo had grown 13 feet longer and weighed twice as much as its XF-88A predecessor. The airframe was sufficiently different that the Air Force assigned it a new designation of F-101A.

The F-101A would be, at the time, the largest single-seat fighter ever built—67 feet 5 inches long and weighing over 48,000 pounds fully loaded. Although the wing had been slightly enlarged by increasing the chord of the inboard half of each panel, total area was still a relatively small 368 square feet, producing prodigious loading of 135.9 pounds per square foot (the highest of the Century Series in original configuration). To improve yaw stability at anticipated higher speeds, the F-101A possessed twice the vertical tail surface of the XF-88, and the all-moving horizontal stabilizer was repositioned near the top of the fin. Internal fuel capacity increased from 734 to 2,341 gallons, augmented by two 450- gallon external drop tanks. Provisions were also made for in-flight refueling via either flying boom or probe-and-drogue systems to extend the plane’s combat radius even farther. An APS-54 search radar provided all-weather capability, and heavy firepower came from four 20mm cannons, three Hughes GAR-1 Falcon radar-homing missiles and up to 12 unguided rockets.

Before the final design was fixed, the Air Force expanded the fighter’s potential mission uses by adding the capability to carry a nuclear weapon on an external rack. Following mock-up inspection in July 1952, the Air Force issued a relatively small production contract for 39 F-101As. Production of the type was virtually assured by applicable procurement policies (i.e., the so-called Cook-Craigie Production Plan, which eliminated the experimental prototype stage in favor of proceeding directly to limited production status). Air Force officials had nonetheless become dubious about the strategic bomber escort mission and had no firm agenda for alternative roles in which the new plane might be used. Not surprisingly, a decision was made to limit production to the initial procurement until military acceptance testing and evaluation was well underway.

The first F-101A was completed in August 1954 and shipped to Edwards Air Force Base, where it made its maiden flight on September 24 with McDonnell test pilot Robert C. Little at the controls. Early testing indicated impressive performance—a top speed of Mach 1.54 (1,009 mph), an initial climb rate of 44,100 feet per minute, a service ceiling of 49,450 feet and a maximum range of 2,186 miles. It also revealed aerodynamic flaws that were serious enough, in May 1956, for the Air Force to halt production pending resolution of its concerns.

The most serious problem was a treacherous “pitch-up” tendency encountered in both high and low airspeeds ranges at certain G levels and angles of attack, frequently followed by engine compressor stalls that led to loss of power or total flame-out. If the pitch-up—an uncontrollable flat spin condition oscillating between 20 and 70 degrees nose up—occurred below 15,000 feet, Voodoo pilots were under standing orders to eject. The pitch-up problem was substantially remedied (though not corrected) by installing a pitch inhibitor that would not allow the stick to be pulled past specific points at specific speeds, and the intakes and engine ducting were redesigned to diminish the possibility of compressor stalling. After what amounted to approximately 2,000 engineering changes, the hold order on F-101A production was finally lifted in November 1956, and the type was accepted for operational service in early May 1957.

Development and testing of the photoreconnaissance version, the RF-101A, followed the fighter version by about 18 months, but due to the setbacks in the fighter program, the photorecon version entered operational service at virtually the same time. The RF-101A made its first flight in June 1956 and differed from the fighter mainly in carrying 150 gallons of additional internal fuel and having a lengthened nose that housed three vertical and two oblique Fairchild cameras in place of the search radar and 20mm guns. The RFs shared the capability to deliver a single nuclear weapon carried on a centerline rack and were marginally faster than the Fs due to reduced weight.

F-101As became operational in May 1957 with the 27th Strategic Fighter Wing in their original bomber escort role. However, by this time SAC had decided to abandon the long-range fighter concept. Even with its above-average range, the Voodoo could not escort the bombers (B-36s and by that time B-47s and B-52s) all the way to their intended targets. The F-101A’s career might have ended then and there but for the intervention of Tactical Air Command, which saw potential in the big fighter as a tactical nuclear weapons delivery platform. Thus in mid-1957 the 27th Strategic Fighter Wing became the TAC-controlled 27th Fighter-Bomber Wing, and all F-101As were thereafter retrofitted with the low-altitude bombing system and other apparatus needed to complete their new function as nuclear strike fighters. By late November 1957, the last of 77 F-101As had been delivered to the Air Force, 50 of them assigned to operational units, with the remaining 27 held for experimental and test purposes. F-101As served in a frontline role until 1966, after which they were phased out and turned over to Air National Guard units.

The first of 35 production RF-101As was delivered to the 363rd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing (TRW) at Shaw Air Force Base, N.C., in May 1957. It was the first supersonic reconnaissance aircraft in the Air Force inventory, and on November 27, 1957, as part of Operation Sun Run, four RF-101As set a new transcontinental speed record. They flew round-trip between McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey and March Air Force Base in California in six hours, 46 minutes and 36 seconds (average speed 721.85 mph).

In the mid- to late 1960s, RF-101As were used as reconnaissance trainers and were all phased out of the active Air Force inventory by 1971. A few serviceable examples, following conversion to RF-101G standards, were transferred to Air National Guard units.

Pilots who flew the Voodoo were impressed by its performance, dubbing it the “One-O-Wonder,” but they also considered it very unforgiving. Colonel C. Robert “Oz” Osborne Jr. said: “The F-101 was a lady—a fantastic airplane, but touchy, very touchy. It had to be flown properly.” Air Force test pilot Richard Baird echoed that sentiment: “It’s the biggest by-the-book fighter I’ve ever flown—the Voodoo would bite you! You really had to fly it strictly by the book.” And reconnaissance pilot Colonel Jonathan Gardner noted that “the first ride, you didn’t fly it—you hung on to it!”

The improved F-101C and RF-101C were both ordered in March 1956. The Cs were externally identical to the A models but had strengthened airframes to accept a higher load limit (6.33 G to 7.33 G), and in the case of the fighter version were equipped from the start as tactical fighter-bombers. All of the 47 F-101Cs built were delivered to the Air Force in 1957-58, serving with the 81st Tactical Fighter Wing as nuclear strike aircraft until they were phased out in 1965-66. The F-101C was the fastest tactical fighter in operational service until the advent of the Lockheed F-104, and on December 12, 1957, a stripped-down example set a new world speed record of 1,204 mph (Mach 1.83).

The RF-101C, built in greater numbers than its fighter counterpart, entered operational service in September 1957, and the last of 166 was delivered in March 1959. RF-101Cs saw wide service with the U.S.- based 363rd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, the Europe-based 66th TRW and the Far East–based 67th TRW. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, RF-101As and Cs of the 363rd TRW flew low-level reconnaissance missions over Cuba.

The RF-101C was the only Voodoo variant to see combat in Vietnam; in fact, as early as 1961, RF-101Cs of the 67th TRW, operating out of Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa, began making surveillance flights over Laos and South Vietnam. In 1965 actual combat operations commenced when RF-101Cs of the 20th TRS, 67th TRW, moved to Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base and began flying reconnaissance sorties over North Vietnam. During the same time period, 45th TRS Voodoos moved to Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base in South Vietnam to cover operations in the South, and served as pathfinders for the first bombing mission against the North on February 8, 1965. Between 1965 and 1970, 33 RF-101Cs were lost to enemy anti-aircraft and missiles, and one to a North Vietnamese MiG-21.

Major Jerry D. Lents described a mission out of Tan Son Nhut in search of surface-to-air missile sites with Captain Jack W. Weatherby that resulted in one such loss. Lents recounted: “We let down to 200 feet and crossed into North Vietnam at our redline speed of 600 knots….Suddenly Jack came up on the radio…and announced: ‘I’ve got a hit. I’m breaking off to the north!’ I saw the hole in his aft fuselage section, slightly above and forward of the afterburners. I crossed over him during our turn and replied: ‘Yes, Jack, you’ve got a hole through the fuselage.’ Then I saw a little fuel start to come out of the fuselage. I called, ‘There’s a little fuel coming out but it’s not bad.’ Then I saw a little flame start to come out of the hole, and I yelled: ‘Jack! You’re on fire! Get out! Get out! Get out!’ It blew up—the whole tail section came off and tumbled back. The fuselage was one big fireball. We had only been at 200 feet, but his whole airplane and 13-14,000 pounds of fuel was consumed in the air by that fireball. Very little of it hit the ground. No black smoke. Nothing.” Captain Weatherby was posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross.

Starting in late 1967, as more RF-4Cs arrived to take over reconnaissance duties, Voodoos were restricted from operations over North Vietnam. They were all ultimately withdrawn from the combat zone by late 1970. Upon their return to the States, RF-101Cs were retired from active U.S. Air Force service and many were turned over to Air National Guard units.

In 1965, 29 F-101As and 31 F-101Cs were modified under the new designations RF-101G and RF-101H, respectively, to serve as unarmed reconnaissance aircraft with Air National Guard units. The modification entailed removal of radar and armament and the installation of a nose cone housing cameras and new electronic components. RF-101Gs and Hs were operated by three Air National Guard units: the 154th TRS in Arkansas, the 165th TRS in Kentucky and the 192nd TRS in Nevada. In early 1968, the seizure of the U.S. naval surveillance vessel Pueblo by the North Koreans led President Lyndon B. Johnson to activate all three Air National Guard Voodoo units. Each served a rotational tour at Itazuke Air Force Base, Japan, and compiled impressive records, flying 19,715 tactical hours in 11,561 sorties and exposing 841,601 feet of aerial film. The last single-seat reconnaissance Voodoos were removed from National Guard service in 1976.

The most numerically important and longest-lived Voodoo was the two-seat, all-weather fighter-interceptor version, the F-101B. By the end of 1953, the Air Force’s ambitious two-step interceptor program with Convair—the Mach 1 F-102A scheduled to be followed by the Mach 2 F-102B (redesignated F-106A in 1956)—was seriously behind schedule. An aircraft was needed to plug the gap between this so-called Ultimate Interceptor and the subsonic Northrop F-89 Scorpions, Lockheed F-94 Starfires and North American F-86D Sabres serving with Air Defense Command. ADC’s express mission was strategic defense—to intercept and destroy Soviet bombers en route to the United States before they reached our shores.

Late in 1953 the Air Force asked aircraft manufacturers to submit proposals for a new missile-armed, all-weather interceptor under the classification Weapons System (WS) 217A. Northrop responded with an advanced version of the F-89, and North American proposed an all-weather version of the F-100. McDonnell offered either a single or two-seat adaptation of the F-101 that would incorporate new fire control and missile systems and use more powerful Wright J67 engines (license-built copies of the British Bristol Olympus that were supposed to produce 22,000 pounds static thrust each). The Air Force selected McDonnell’s proposal in mid-1954, specifying the two-seat version, and issued a letter of intent in March 1955 for an initial batch of 28 aircraft and potential production of 68 more. The expectation was that the first flight would take place in mid-1956 and the type would enter operational service in early 1958.

After the letter of intent was issued, McDonnell requested the designation F-109 for the airframe portion of the WS-217A project, but the Air Force, evidently conscious of the funding obstacles associated with “new” aircraft, as opposed to “improvements” to an existing type, called it the F-101B. Although McDonnell had the F-101B mockup ready for inspection by September 1955, the entire Voodoo program was put on indefinite hold while the aforementioned aerodynamic problems with the F-101A were being ironed out.

Further delays and uncertainties with the J67 engines led to a decision to use Pratt & Whitney J57-P- 55 power plants, which featured longer afterburners and a thrust rating of 16,900 pounds per engine. The F-101B shared the center and aft fuselage sections and tail group of the F-101A series, and, other than bulged wheel well doors to house larger tires, the same wing planform. But the F-101B introduced a completely new, 4-foot-longer forward fuselage section with a tandem cockpit layout for the pilot and radar operator. Also new was a Hughes MG-13 tracking and fire control system, essentially an upgrade of the E-6 system already utilized in the F-89D, and a rotary weapons bay that held four Hughes Falcon semi-active radar (GAR-1) and infrared (GAR-2) missiles.

The first F-101B took off from Lambert Field in St. Louis on March 27, 1957, a year behind schedule, and the Air Force spent nearly two more years conducting extensive tests and evaluations before releasing the Voodoo interceptors to operational service. Flight performance met expectations—a top speed of Mach 1.66 (1,094 mph), a combat ceiling of 51,000 feet and a normal range of 1,387 miles—but the F-101B had other problems that seriously hampered its operational effectiveness. The radar operator’s position was poorly designed, and little could be done to improve it other than minor adjustments. Even more worrisome, the MG-13 fire control system did not adequately control the weapons on a platform as fast as the F-101. A proposal to replace the system with the more advanced MA-1 developed for the F-106 was rejected because of the cost involved.

Deficiencies notwithstanding, F-101Bs became operational with the 60th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (FIS) at Otis Air Force Base in Massachusetts on January 5, 1959. On the plus side, the two-seat Voodoos had been exhaustively tested by the time they reached ADC, and they finally gave the Air Force an interceptor capable of advanced performance at “affordable” cost ($1.7 million per plane, compared to $4.7 million for an F-106A).

By the end of 1960, no fewer than 17 ADC squadrons were equipped with F-101Bs. Production ended in March 1961 with a total of 480 aircraft delivered. Beginning in 1959, McDonnell undertook a modification in which approximately one out every four F-101Bs would be fitted with dual controls while retaining full ADC mission capability. Used for conversion and operational training under the initial designation TF-101B, these aircraft were redesignated F-101Fs in 1961 after 79 examples had been modified.

Late-production F-101Bs boasted upgraded fire control systems and the ability to carry two nuclear-tipped, unguided Genie MB-1/AIR-2A missiles in place of two Falcons. In a modernization program (Project Bold Journey) completed between 1963 and 1966, most F-101Bs were fitted with infrared sensors to facilitate tracking of hostile aircraft regardless of radar jamming and also received a much-improved pitch control mechanism that functioned through an automatic flight control system.

F-101Bs/Fs began to be phased out of Air Force service in 1969 without having fired a shot in anger, and the last active-duty squadrons operating the type, the 60th and 62nd FISs, retired their Voodoos in April 1971. Simultaneously, F-101Bs/Fs were delivered to Air National Guard units, starting with the 116th FIS, Washington ANG, in November 1969, and ultimately went on to fully equip eight fighter-interceptor units in seven different states.

The last Guard unit to operate F-101Bs, the 111th FIS, Texas ANG (the unit in which President George W. Bush flew F-102s), gave up its last Voodoo in 1981. The Air Force retained a small number of F-101Bs after 1971 for fighter-interceptor training, and the last of those was retired in September 1982.

E.R. Johnson, a frequent contributor to Aviation History, writes from the Ozark region of Arkansas. A U.S. Navy veteran and past president of the Arkansas Aviation Historical Society, he currently serves as a mission pilot and aerospace education officer in the Arkansas Wing of the Civil Air Patrol. Additional reading: McDonnell F-101 Voodoo, by Robert F. Dorr; Voodoo, by Lou Drendel and Paul Stevens; and Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems, Vol. 1: Post–World War II Fighters, published by the Office of Air Force History.

Originally published in the March 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.

Inspired to add the one-oh-wonder to your collection of Century Series models? See our exclusive build!