Sieges in American history may lack castles and siege engines, but those who endured them demonstrated ample bravado.

The concept of the siege is as old as human conflict itself, dating from man’s earliest efforts to “fort up” against hostile forces. The written record of American sieges stretches back to colonial times. Some of these sieges were monumental, some personal, others simply quirky. All met the requisite criterion: people on the inside striving desperately to keep people on the outside from either getting in or forcing them out.

During the French and Indian War what now constitutes upstate New York was a hotly contested battleground between the colonists of British America and those of New France, the 32-mile-long stretch of Lake George forming an uncertain barrier between the two. In late 1755 the British constructed Fort William Henry on the southern shore of the lake as a potential staging ground for incursions into Canada. The British fortress looked impressive. Built on an irregular square, it boasted bastioned corners and 30-foot-thick walls, surrounded on three sides by a dry moat and on the fourth by the lake itself. The walls, however, comprised earthen berms faced with logs and—as the garrison would soon discover—were no match for artillery.

Some 16 miles southeast of Fort William Henry stood Fort Edward, on the banks of the Hudson River. Connecting the two was a recently cleared wilderness road, over which Fort William Henry could presumably draw support from Fort Edward should the French attack.

Attack they did. In the summer of 1757 French Brig. Gen. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Gozon, resolving to launch a preemptive strike, assembled a formidable army of some 6,200 regulars and militia and 1,800 Indians from allied tribes, supported by 36 cannon and five mortars.

Getting wind of the French plans, Maj. Gen. Daniel Webb, commanding at Fort Edward, reinforced the garrison at Fort William Henry to around 2,400 men. The fort itself could only house up to 500, however, so the bulk of the force occupied an entrenched camp within a half-mile southeast of the fort. A number of British soldiers were suffering from smallpox and were quartered in either the fort’s makeshift hospital or sick huts.

After boating down Lake George with the bulk of his army, Montcalm arrived outside Fort William Henry the night of August 2–3. The next morning, having failed to convince British Lt. Col. George Monro to surrender his post, the French general commenced siege operations. In the days that followed, Montcalm’s gunners kept the British under near continual bombardment while his sappers dug trenches toward the fort, bringing the French guns ever closer. Monro sent several couriers to Fort Edward, appealing for help. But Indians and militia blocked the road, and on August 4 they shot down a rider carrying a reply from Webb. The dispatch they recovered from the courier’s body advised Monro to surrender. Three days later, as the French closed to within 1,000 yards of the fort, Montcalm shared the intercepted missive with the British commander. On August 9, with little hope of relief, Monro capitulated.

Montcalm offered generous terms: He would allow the British to march out in parade order, under their colors, in return for a pledge not to bear arms against the French for 18 months. They could keep their personal belongings, weapons and one symbolic cannon, but no ammunition. French doctors would tend their sick and wounded, who would be returned to Fort Edward when well. The terms seemed too good to be true—and they were.

The Indians, angered by Montcalm’s leniency, plundered the surrendered fort and killed 17 of the incapacitated soldiers. The next morning, as the British column marched away ostensibly under French escort, the Indians attacked, at first robbing and beating, then killing and scalping unarmed soldiers and their families. Discipline among the British collapsed, as men, women and children broke for the woods, pursued by hundreds of screaming Indians.

In coming days only about 500 of the 2,308 British troops and followers who had surrendered made it to Fort Edward. Lurid reports claimed the Indians had butchered as many as 1,500. But scores of the British had escaped, and the Indians took hundreds more captive. A more accurate count of those killed and missing falls between 69 and 184. In the weeks following the attack dozens of fugitives trickled into Fort Edward and other British bastions, while French and British authorities successfully negotiated the release of hundreds more. But the slaughter remained a blot on Montcalm’s otherwise impressive military record.

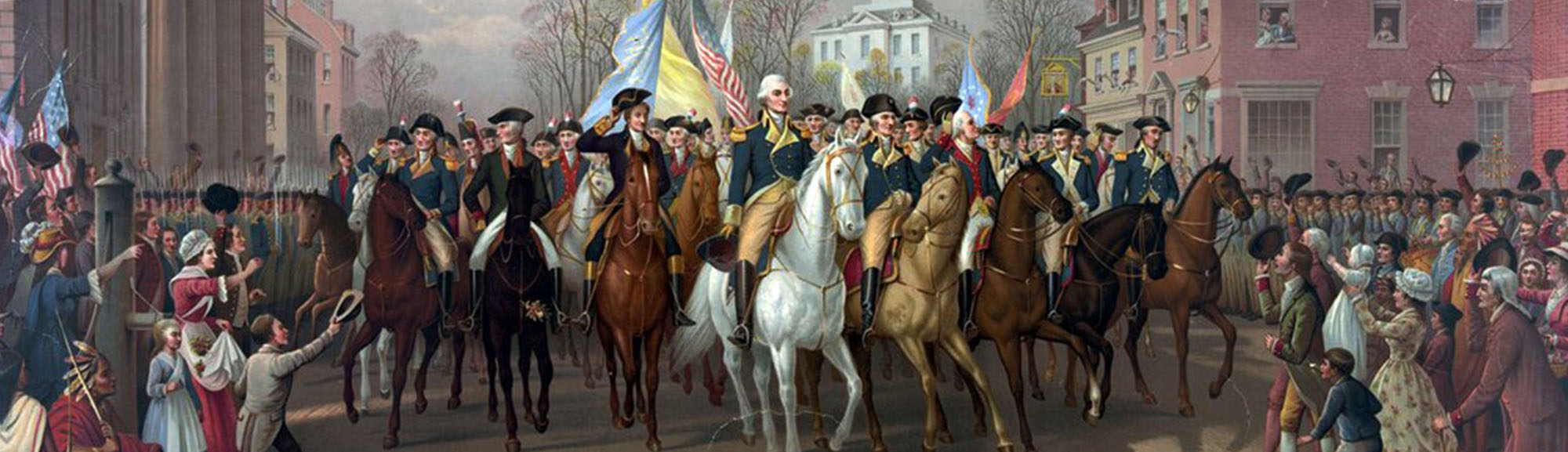

The first siege of the American Revolution followed on the heels of the April 19, 1775, Battles of Lexington and Concord. Lasting nearly a year, it resulted in a key strategic victory for the young nation and its commander in chief, George Washington.

Pursuing the British from Lexington and Concord, Mass., the Patriots blockaded the land approaches to Boston and established a siege line from Roxbury to Chelsea, corralling Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage and his troops within the strategically vital town. The only remaining access was via Boston Harbor, through which, over the months that followed, the British reinforced the garrison to a peak of some 6,000 troops.

At that point the Continental Army was little more than a disparate gaggle of ill-trained, ill-equipped militiamen who felt little kinship with one another. By that summer desertion had further thinned its ranks. Worse yet, Washington lacked sufficient artillery to mount an effective siege. Arriving at a solution, the American commander sent Colonel Henry Knox, a resourceful young officer, to Fort Ticonderoga, N.Y., which Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen had captured from the British that May. His mission? To haul the fort’s artillery back to Boston. In early December, after selecting some five dozen cannons, mortars and howitzers from Ticonderoga’s arsenal, Knox proceeded to haul and float his 60 tons of ordnance nearly 300 miles through winter gales down Lake George, across icebound rivers, over snow-covered mountains and through dense forests, finally delivering the guns to Washington in Boston in late January 1776.

On the night of March 4–5 Washington ordered a diversionary bombardment while hundreds of Patriot soldiers silently mounted guns atop Dorchester Heights, overlooking the British troops and ships. Finally wielding sufficient firepower, the American commander gave the British little choice but to evacuate the town. On March 17, with the arrival of favorable winds, General William Howe—who had replaced Gage as garrison commander—embarked his troops and thousands of terrified Loyalists and sailed for Nova Scotia. Despite its shortcomings, the fledgling Continental Army had successfully besieged a British army for nearly a year.

In the mid-1880s the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA), comprising the territory’s leading cattle barons, suffered a spate of bad luck. First came drought and the resultant dearth of grass. Then came the “Big Die-up”—two consecutive winters (1885–86 and 1886–87) so brutal they killed 80 percent of the stock, bankrupted many of the big spreads and all but wiped out the cattle industry.

Then came organized rustlers. While the cattlemen could do nothing about the weather, they could certainly put an end to human depredations. Consequently, in 1892 WSGA members resolved to invade Johnson County, suspected hotbed of rustling in the region. They compiled a hit list of 70 names, including a number of small ranchers who, while perhaps guiltless of rustling, had had the temerity to start a competing association. Topping their list was Nate Champion, a Texas-born cowboy who had made his reputation in Wyoming—first as a top hand, then as owner of a small herd. Champion was admired by many and trusted by most. But as unofficial leader of the small ranchers, he represented a thorn in the side of the big cattle interests. Champion had survived an earlier attempt on his life, and the cattlemen were eager to keep him from implicating them in that attack.

The barons hired nearly two-dozen Texas gunmen at $5 a day, plus a $50 bounty for every man on the list they killed. Far from a clandestine mission, their plan had the tacit support of Wyoming Gov. Amos W. Barber, a onetime association member, who would rally a far higher authority to their defense when things didn’t go as planned. The little army’s first stop was Champion’s remote cabin on the KC Ranch, south of Buffalo.

At dawn on April 9 the party of 52 armed cattlemen and hired killers—joined, bizarrely, by two newspaper reporters—surrounded the cabin. Inside were an unsuspecting Champion, partner Nick Ray—whose name was also on the list—and two visiting freighters. The men outside quietly nabbed the visitors as they emerged to collect water. But when Ray left the cabin, they opened fire, mortally wounding him. Moments later Champion bolted from the cabin. Rapid-firing his rifle at the attackers, he ran to his partner, grabbed him by the collar and—bullets kicking up dust all around him—dragged Ray back inside.

The besieged cabin soon came under a torrent of gunfire from the stable 75 yards to the northeast, from the riverbank to the northwest, from behind the house and from a ravine 50 yards south. Remarkably, as his partner lay dying and his own hopes of mercy or rescue ebbed away, Champion opened a small notebook and began to write:

“Me and Nick was getting breakfast when the attack took place,” he opened. “Nick is shot but not dead yet. I must go and wait on him.” Two hours later he wrote, “Nick is still alive.” Between entries he shot back whenever a target presented itself. The firing remained intense. “Boys, there is bullets coming in like hail.” Around midmorning Champion wrote, “Nick is dead—he died about 9 o’clock.” He then bluntly assessed his situation: “I don’t think they intend to let me get away this time.”

“Boys, I feel pretty lonesome just now,” Champion mused as the siege dragged on past noon. “I wish there was someone here with me so we could watch all sides at once.” By 3 p.m. he’d begun to lose hope. “It don’t look as if there is much show of my getting away.”

Late that afternoon Champion heard the sound of splitting wood, as the invaders filled a wagon with splintered pitch pine and hay. “I think they will fire the house this time,” he wrote. He was right. While the others kept up a steady fire, a handful of men ran the burning wagon up against the outside of the cabin. Flames engulfed the structure as Champion wrote his final entry: “The house is all fired. Goodbye, boys, if I never see you again.”

Signing the entry, he pocketed the notebook and, armed with a rifle and six-shooter, bolted from the cabin toward the nearby ravine—straight into the muzzles of waiting gunmen. Champion got off a single shot before his attackers poured round after round into him. After inspecting their quarry’s lifeless body, one of the killers pinned a hastily scrawled placard to Champion’s bloody vest: Cattle Thieves, Beware!

By delaying the invasion a day, Champion had allowed an alert neighbor to get word to Buffalo, where Johnson County Sheriff William “Red” Angus threw together a force of more than 200 outraged citizens. They intercepted the invaders on the morning of April 11, trapping them in the barn of a nearby ranch. Within hours, however, Gov. Barber telegraphed President Benjamin Harrison, pleading on behalf of the now besieged besiegers. On Harrison’s authority a cavalry troop from Fort McKinney soon rescued the cattlemen and their hired killers. Ultimately, not a single invader was convicted of a crime. The Texans went home after collecting their blood money, and the cattle barons returned to their ranches. Nonetheless, by his stand in the face of certain death Champion had thwarted mass vigilantism in the lawless early days of Wyoming.

One of the most storied sieges in the history of westward expansion began on June 27, 1874, at Adobe Walls, a settlement amid the ruins of an abandoned Texas Panhandle trading post.

Ten years earlier at Adobe Walls some 400 enlisted men and Indian scouts of the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Cavalry under Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson had successfully fought off several thousand Comanche, Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache warriors. History was set to repeat itself. The buffalo trade was brisk in 1874, and that spring a handful of Kansas entrepreneurs had built a makeshift trading post near the ruins to service the dozens of hunters ranging the surrounding countryside. By June it comprised two stores, a corral, a blacksmith shop, a restaurant and, not surprising, a saloon.

Determined to drive out the intruders, several hundred of the region’s Comanches and Cheyennes, along with a handful of Arapahos and Kiowas, banded together for what Comanche medicine man Isa-tai had guaranteed would be a successful campaign. He further promised his “magic” would protect the warriors from the buffalo hunters’ bullets.

At dawn on the 27th the army of allied Indians, under the leadership of Isa-tai and Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, swooped down on the encampment. Inside the complex were one woman and 28 very surprised merchants, drovers, hunters and skinners. Among them were Bat Masterson and Billy Dixon, two young men destined to become Western legends. Among the hunters were veterans of earlier Indian fights. They were proficient marksmen, and their favored weapon was the long-range .50-caliber Sharps rifle. From 1,000 yards a single well-aimed round could kill a buffalo, let alone a man. Inside the stores were cases of the Sharps “Big Fifties” and thousands of rounds of ammunition. They outshone the Indians’ weapons in range, power and accuracy.

When the warriors attacked, the besieged buffalo men took refuge in the saloon and both stores, sheltering behind stacked hides, grains sacks and anything else they could find. The Indian fire was daunting, and three men died in the initial onslaught. “At times,” Dixon recalled, “the bullets poured in like hail and made us hug the sod walls like gophers.” As sod doesn’t burn, at least there was no danger of being burned out, and the defenses held.

Over the next several days the buffalo men repelled repeated charges, during which some foolhardy warriors rode in close enough to pound on the doors and windows. Digging gun ports through the sod walls, the hunters picked off their exposed attackers one by one. “We tried to storm the place several times,” Quanah recounted, “but the hunters shot so well, we would have to retreat.”

It seemed no matter how far they withdrew from the sod buildings, the .50-caliber rounds continued to find them. On the third day of the siege Dixon reputedly dropped an Indian from his horse at a distance of nearly a mile. By then the Indians belief in Isa-tai’s prediction had faded. And when Quanah himself took a blow to the shoulder from a spent bullet, they wholly lost faith. Although they remained in the area a few more days, the warriors staged no more direct attacks on the encampment. When the last of them drifted away, the buffalo men emerged from their fortifications. The bodies of more than a dozen warriors still lay on the surrounding plain. In addition to the three buffalo men killed in the initial assault, a fourth died as he descended a ladder and his own gun accidently discharged, tearing off the top of his head.

The allied Indians raided the area throughout the summer, destroying settlements, outlying homesteads and wagon trains and killing an estimated 190 settlers over a 1,000-mile swath from Texas across the Plains states into Colorado. As devastating as the raids were, they only prompted relentless military pursuit, resulting in the ultimate subjugation and relocation of the Southern Plains tribes and the opening of the region to permanent settlement. The failed siege of Adobe Walls was merely a harbinger of the inevitable defeat that followed.

Freelance writer Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon and The Slave Next Door. For further reading he recommends Adobe Walls: The History and Archaeology of the 1874 Trading Post, by T. Lindsay Baker and Billy R. Harrison, and Wyoming Range War: The Infamous Invasion of Johnson County, by John W. Davis.