But the Eighth Kansas’s spirited charge helped the Army of the Cumberland take the heights

Doubt was on Colonel John A. Martin’s mind as he stared at the Confederate defenses atop Missionary Ridge.

It was November 25, 1863, about 4 p.m., and the 8th Kansas Infantry’s commander had become certain a Federal attack up that rocky hillside outside Chattanooga, Tenn., was inevitable.

10th governor. (Kansas Historical Society)

“[O]n the centre we had the work to do,” Martin later wrote to Freedom’s Champion, the newspaper he owned in his hometown of Atchison, Kan. “[S]tronger grew the conviction that the attempt would be made [and] stronger grew the conviction of its utter madness and folly. I could not believe that any courage, however desperate, could carry the height bristling with a hundred pieces of artillery, and defended by a force nearly, if not quite, as large as ours. But I felt that however fearful the risk of utter defeat, the attempt would be made, and I shuttered [sic] as I looked down the lines of brave men, and thought how many of them would that day sleep their last sleep.”

What followed would be breathtaking, a signature moment not only for Martin and his 8th Kansas but the entire Army of the Cumberland. That afternoon, the 8th Kansas found itself at the forefront of a Federal charge up Missionary Ridge.

It proved, however, not to be an attack of “utter madness and folly.” In little more than 30 minutes, in fact, the Confederates had been overwhelmed, chased off that formidable ridge, and the battles for Chattanooga all but decided. ¶ The loss of Missionary Ridge soon forced Army of Tennessee commander General Braxton Bragg to order a retreat into Georgia, the Confederates another step closer to ultimate defeat.

Until Missionary Ridge, the Army of the Cumberland had experienced modest success in the war. As the Army of the Ohio, it had done well at Mill Springs, Ky., in January 1862, and at Shiloh three months later. A mistake-plagued effort at the October 1862 Battle of Perryville, however, produced both a tactical loss and a strategic victory. Shortly afterward, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans replaced Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell and gave the army its new name. But despite a respectable-enough triumph at Stones River in early January 1863 and then success in the Tullahoma Campaign in June, Rosecrans did not impress the War Department authorities in Washington, D.C., including President Abraham Lincoln, all frustrated by Old Rosy’s cautious and deliberate style of command.

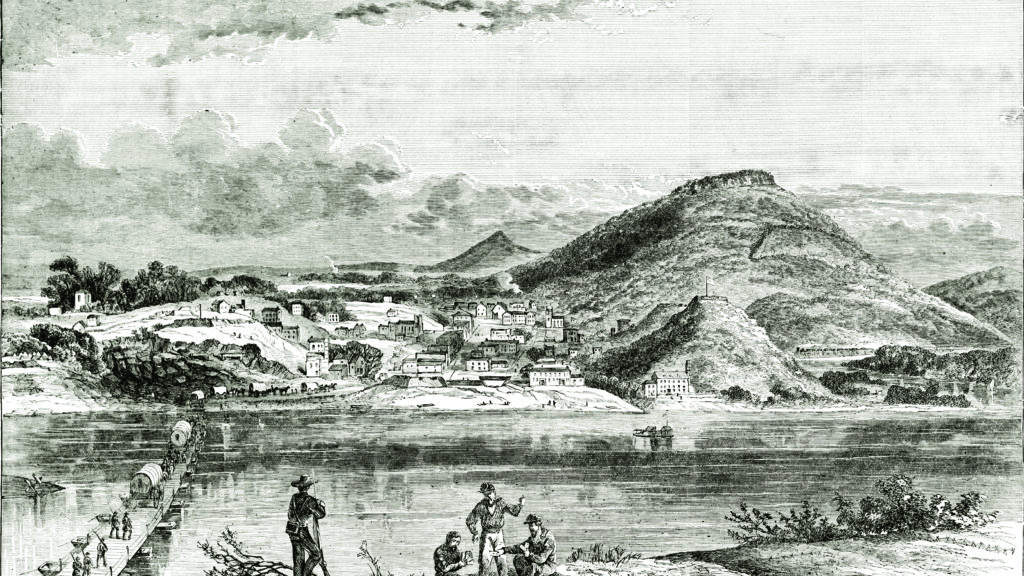

The alarming Union defeat at Chickamauga on September 19-20, which produced a frantic Federal retreat north into nearby Chattanooga, was finally the end for Rosecrans. The general’s failure to secure Lookout Mountain, Raccoon Mountain, and Missionary Ridge during the retreat—all occupied in force by the Confederates—had left the Army of the Cumberland trapped within the city, with access to only one vulnerable wagon supply route. For the increasingly hungry Federal soldiers, it was a time of gloom and despair.

On October 16, the man who had engineered victory at Vicksburg, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, was appointed to command a new Division of the Mississippi, overseeing the Departments of the Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee. Grant quickly replaced Rosecrans with Maj. Gen. George Thomas; Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman assumed command of the Army of the Tennessee; and embattled Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker—still reeling after being stripped of command of the Army of the Potomac days before Gettysburg—was sent to Chattanooga as commander of two detached Army of the Potomac corps, the 11th and 12th.

Across the lines, the Army of Tennessee was having its own crisis of command. General Braxton Bragg faced pressure from his corps commanders to move on Chattanooga quickly before the opportunity might be dashed by the arrival of Federal reinforcements under a new, more aggressive leader such as Grant. But Bragg, much like Rosecrans had been, was seemingly paralyzed by the immense casualties his army had suffered at Chickamauga. In addition, Bragg’s moves to reassign some of his subordinates led to a near mutiny among his senior officers, who wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis asking for Bragg’s removal. For now, Bragg would win Davis’ support. Two of his corps commanders, Maj. Gens. D.H. Hill and Simon Bolivar Buckner, were dismissed, and Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk was reassigned to a military command in Mississippi.

Lieutenant General James Longstreet also suffered repercussions for his criticism of Bragg. On November 4, Bragg ordered Longstreet to march with his two Army of Northern Virginia divisions to Knoxville, 70 miles to the north, in an effort to wrest control of the city from Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Federal army.

Grant arrived in Chattanooga shortly after assuming his new command and quickly set about finding a solution for the supply-strapped Army of the Cumberland. Grant endorsed a plan that former Army of the Potomac corps commander Brig. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, now the Army of the Cumberland’s chief engineer, had apparently presented first to Rosecrans—an operation to create a so-called “Cracker Line” that would streamline the flow of supplies into Chattanooga. Before the Cracker Line (named for the standard issue hardtack bread, or “crackers,” that was a staple of the Federal troops’ diet), it took an eight-day, 60-mile journey through difficult terrain to transport needed supplies. Beginning in Union-held Bridgeport, Ala., Federal supply trains would head north through Tennessee’s Sequatchie Valley to Anderson’s Crossroads and then head back to Chattanooga from the northwest. Thousands of draft animals were lost during the trek, and the supply wagons were also the victims of attacks by Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry.

The first supply convoy arrived at Kelly’s Ferry on October 29, and the much-shortened water and land route, out of range of Rebel guns, soon rectified the Federal supply crisis in Chattanooga.

When Sherman arrived in Chattanooga in mid-November, the Federal presence in and around the city swelled to 86,000 effectives. With two divisions now en route to Knoxville to deal with Burnside, the Confederate force stood at about 33,000. Bragg, however, still possessed Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge.

The shipments of hardtack and other supplies, along with reinforcements, reinvigorated the men in the Army of the Cumberland. These veteran soldiers, many of them stout farmers and tradesmen from the states of the Old Northwest, had tasted both victory and defeat in the many months they had served. The men and commanders of these regiments were known for their valor, and some units had already distinguished themselves, such as Colonel John T. Wilder’s mounted “Lightning Brigade,” equipped with Spencer repeating rifles, and the veteran division commanded by Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. But they hadn’t yet gained the same confidence that Grant had in Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee.

In the Army of the Cumberland the 8th Kansas—attached to the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division in Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger’s 4th Corps—was beginning to be noticed. Colonel Martin was a leader devoted to the service of his country, but he also was passionate about the abolition movement. Martin had been a newspaper publisher in Atchison since 1855, when, at the age of 17, he had purchased a proslavery tabloid and turned it into the antislavery newspaper Freedom’s Champion.

When he enlisted in the 8th Kansas, Martin was named its colonel, leading the regiment in all its engagements. As a journalist, he recognized the importance of chronicling the events he had witnessed and experienced. He brought the war home to Kansas in a series of letters to family and his newspaper readers.

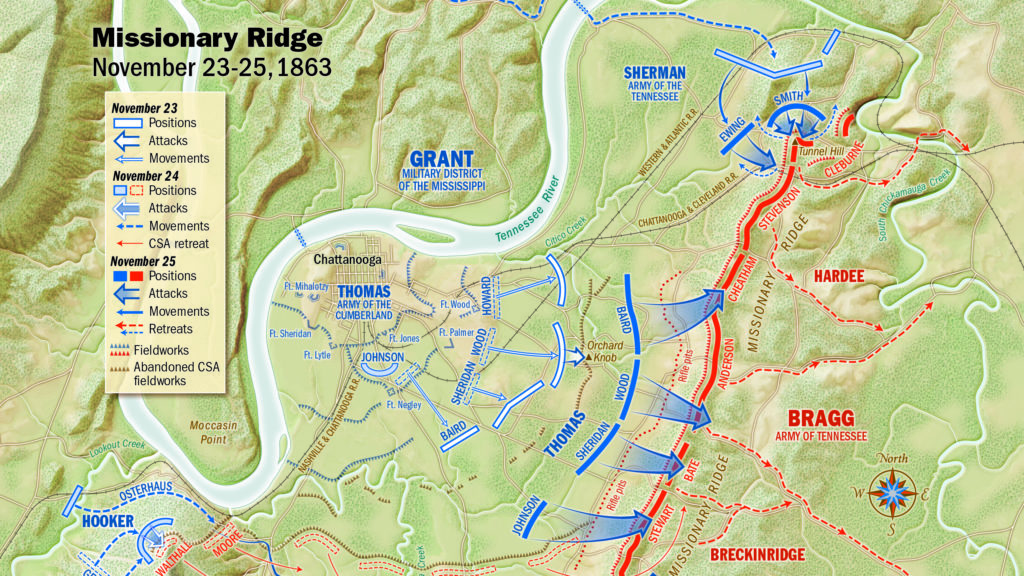

Near the end of November, Grant felt the time to attack had come. He decided to test the Confederate line with a demonstration in front of Missionary Ridge while Sherman secretly positioned his men for the main assault on the north end of the ridge at Tunnel Hill and Hooker prepared to attack Lookout Mountain. On November 23, Thomas ordered the two remaining divisions of Granger’s 4th Corps (Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft’s 1st Division had been sent to support Hooker) to assault Orchard Knob, a rugged 100-foot hill midway between the Federals’ Chattanooga works and the base of Missionary Ridge. With Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s 3rd Division in the lead, supported by Sheridan’s 2nd Division, the assault began at midday, taking on the appearance of a martial parade that troops on both sides ended up watching. Suddenly, with the 8th Kansas manning the skirmish line, Wood’s men charged the hill. Within a few hours, the position was secured, as resistance from the Rebels on Orchard Knob and Confederate artillery on Missionary Ridge was largely ineffective.

Martin later described the assault on Orchard Knob in a letter to his newspaper:

On the 23d our Regiment went on outpost picket duty at daylight. There had been rumors of a contemplated advance for many days past, but it had been so often postponed that our boys had begun to regard it as a joke. A little after noon, however, an order for a general advance was brought to me, with instructions that the Division would form in front of the works around the town and the Eighth would be deployed as skirmishers in front of our line, and at a given signal move forward. The instructions was [sic] that this advance would be simply a reconnaissance in force, to discover the strength of the enemy.

At about two o’clock the bugle sounded the advance, and picket reserves were promptly doubled in the sentinel line, which moved forward. The rebel pickets were only about fifty or a hundred yards distant. The embankment of the railroad separated the two lines. Our boys moved forward in splendid order, and with the greatest impetuosity. The rebels opened a brisk fire on them, but could not stand the assault, and fell back, gathering strength as they reached their own reserves. Our boys dashed after them with hearty cheers, and with such impetuosity that they never recovered from their disorder and we drove them at least a mile taking their first line of rifle-pits and occupying Orchard Knob. Our skirmish then drove on some hundred yards beyond this, nearly to the reserved line, where we were ordered to halt, the Brigade forming behind the first line of rifle-pits. Our Regiment lost three wounded in this advance.

It was a satisfying moment in the conquest for Chattanooga. Still, in Grant’s plan, the Army of the Cumberland was to have only a supporting role. Shortly after midnight, Sherman’s men swiftly and quietly crossed the Tennessee and occupied a hill on the east side of the river—which proved to be the wrong hill. The objective was Tunnel Hill (named for the railroad tunnel that ran through it), which was still a mile away across a broad valley. Texans from Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s Division began to fire on Sherman’s men. Bragg, now realizing the danger to his flank, sent Cleburne’s full division to Tunnel Hill. The Confederates also damaged the pontoon bridge that Sherman’s men had built. By nightfall, Sherman ordered his stymied men to dig in.

On the other side of Chattanooga, the situation was more favorable for the Union forces. The weather, which had bogged down deployment so much that Hooker was commanding one division from each army, turned into a Northern advantage. A thick fog allowed Geary’s division to scale craggy Lookout Mountain undetected. By maneuvering his forces up the mountain and through Chattanooga Valley, in what was aptly labeled the “Battle Above the Clouds,” Hooker had control of Lookout Mountain by nightfall on the 24th.

An encouraged Grant ordered Hooker to continue north and cut off the Confederate retreat route through Rossville Gap in Georgia, which “Fighting Joe” began doing on November 25. Early on the 25th, Sherman restarted his push down the spine of Missionary Ridge. Cleburne had designed an effective defense for his division, with support from Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson’s troops. Sherman signaled Grant that the offensive had stalled. Although Hooker was also being slowed crossing Rossville Gap, he managed to get a foothold on the south end of Missionary Ridge in the afternoon.

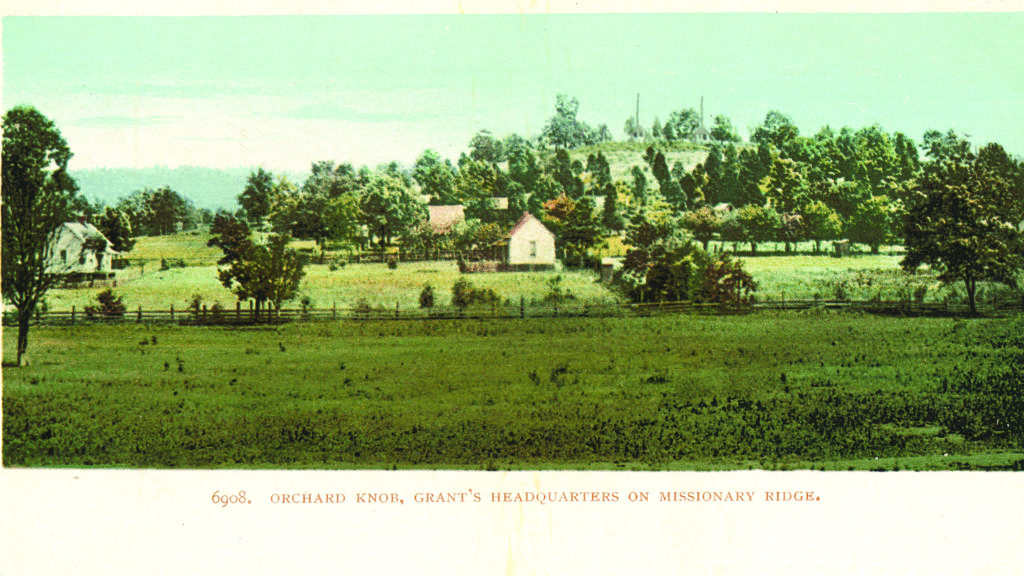

Grant received these reports at Thomas’ new headquarters on Orchard Knob. Despite the performance of Thomas’ army, Grant was hesitant to have it assault the Confederate center. Still, he had to relieve the pressure on Sherman, and in the afternoon ordered Thomas to demonstrate against the rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge, then halt and await further developments. It was a grand sight: Sheridan’s and Wood’s divisions flanked by two others from the 14th Corps. The advance of 20,000 soldiers had to give some trepidation to the Confederate defenders. On Bragg’s orders, the rifle pits emptied after a single volley.

The men of the Army of the Cumberland were reinvigorated. Overrunning the rifle pits, they began to scale the rugged face of the ridge, shocking and angering Grant. The Rebels from the rifle pits could barely keep in front of the charging Union soldiers. Withering Confederate cannon and musket fire, raining down from the ridgetop on friend and foe alike, failed to deter the advance up the ridge. Martin and the 8th Kansas were in the thick of it.

As he would write in Freedom’s Champion:

In front here was a wide bottom, covered with trees and tangled vines; then an open space for probably a hundred yards; then a slight rise of ground; and on the top of this the first line of rebel rifle-pits. Beyond this line stretched another open space of probably fifty yards, and then the hill commenced rising broken, ragged, and in some places almost perpendicular for 300 yards and crowned on the top by a strong barricade of the trunks of trees, filled with earth. From the time we left our own works until we reached the top of these hills we would be subjected to the converging fire of over one hundred pieces of artillery, and the worse and more destructive fire of small arms the moment we emerged from the skirting of forest in front.

Could it be done? I would not doubt, and yet I hardly dared believe.

Ever the journalist, Martin provided a rich, detailed account of the attack on what he called Mission Ridge (as did many others at the time). Mission Ridge, in fact, is how the clash is listed on the regiment’s battle flag (right).

At 2 o’clock [sic] it came—the order I had anticipated—“Advance!” They said afterward that the order was misunderstood—that the first order was only to take the first line of rifle-pits at the foot of the hill. We did not get it so; it was simply ‘Advance’ at the signal—six guns fired in quick succession from Orchard Knob. It would have made no difference, anyhow—a skirmish line could have taken the first line of works, but no army in the world could have held them with[out] at first dislodging the enemy from the summit of the hills, for they were raked from every side.

As Martin wrote, August Willich’s 1st Brigade, part of Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s 3rd Division, was in the center, flanked on the right by Brig. Gen. William B. Hazen’s 2nd Brigade and on the left by Brig. Gen. Samuel Beatty’s 3rd Brigade. To Willich’s left was Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird’s 3rd Division, part of Maj. Gen. John Palmer’s 14th Corps. To the right was Sheridan’s division.

The Confederate defenders directly in the path of General Wood’s division was Brig. Gen. Patton Anderson’s Brigade, which was commanded at that point by Colonel William F. Tucker, with Anderson commanding Thomas Hindman’s Division.

….The troops moved out in front of the rifle-pits and formed in line, the men resting lazily on their guns, but anxiously awaiting the signal. One–two–three–four–five—then a long pause for the sixth gun hung fire—six; and with a loud huzzah along the whole line it advances, steadily, firmly. A moment, and crash—bang, bang, bang—the ball has opened. The summit of Mission Ridge is enveloped in smoke; above us crack the bursting shell, and around us fly the hurling showers of broken fragments. Without an order, the line breaks into a double-quick—brave fellows, they know the sooner the ground is passed over, the greater the safety. They emerge from the woods, and the quick rattle of musketry commences. Not a shot from our side yet. On we go, as fast as the burdened men can travel. We reach the first line of works, and the grey-cons couched behind them throw down their arms, and leap to our side, for their comrades on the hill will not heed their lives while we are there. A halt for a moment behind the works for the men to recover breath—then ‘Forward!’

We had lines before—now they are lost, and the fight becomes a struggle as to who shall be first on top. The crash of artillery is deafening—the air is alive with bursting shell, and musket balls, and solid shot seem to plow up every foot of ground beneath one’s feet. But forward all go. Not a man hesitates or falters. Here and there a regimental color leads ahead, surrounded by half a dozen impetuous spirits whose desperate courage has carried them along.

Lines become shaped like wedges, the points far up the hill, generally headed by the regimental flags and widening to the deep columns behind. Up go these wedge-shaped masses, irresistible in their impetuous force. Now one has reached the summit, and the starry flag is planted on the rebel works—another follows almost simultaneously, and another and the hill is ours!

Cheer after cheer rings out proclaiming victory. Mission Ridge is stormed and the Army is victorious! General officers ride along the lines and are greeted with wild and thrilling huzzahs; cheer after cheer breaks out upon the air and makes the arches of the old wood ring. It was a grand and glorious scene. One never to be forgotten while memory lasts.

Although the unabated charge had not been part of Grant’s original playbook, he and Thomas were summarily impressed. “The pursuit continued until the crest was reached, and soon our men were seen climbing over the Confederate barriers at different points in front of both Sheridan’s and Wood’s divisions,” Grant wrote. “The retreat of the enemy along most of his line was precipitate and the panic so great that Bragg and his officers lost all control over their men. Many were captured, and thousands threw away their arms in their flight.”

In his official report to General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck on December 1, 1863, Thomas wrote: “It is believed…that the original plan, had it been carried out, could not possibly have led to more successful results. The alacrity displayed by officers in executing their orders, the enthusiasm and spirit displayed by the men who did the work, cannot be too highly appreciated by the nation, for the defense of which they have on so many other removable occasions nobly and patriotically exposed their lives in battle.”

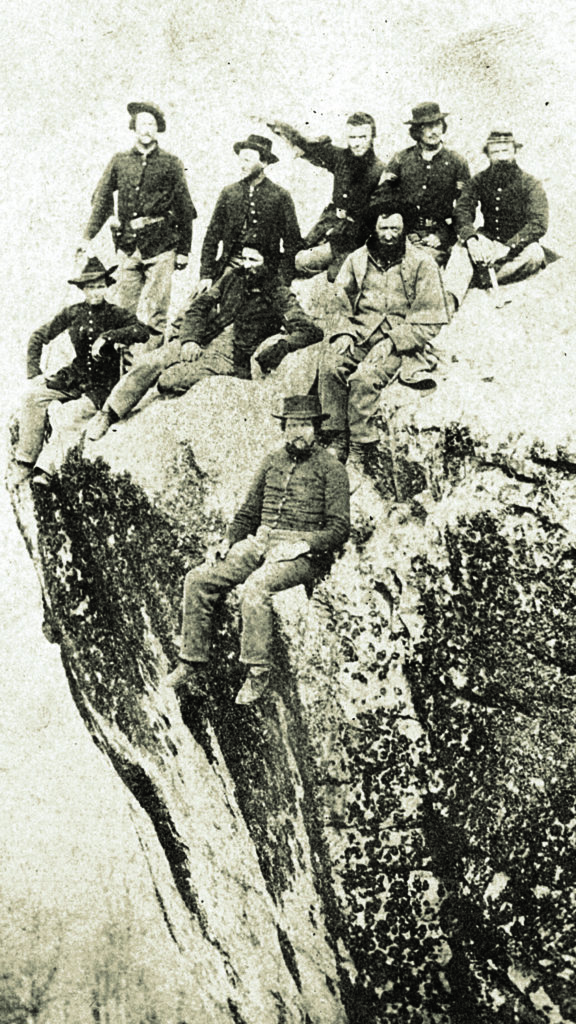

Federal soldiers.(Missouri History Museum)

With Missionary Ridge secured, the Federals pursued the retreating Army of Tennessee for a short distance into Georgia. Confederate Maj. Gen. Cleburne’s Division proved enormously effective as Bragg’s rear guard, and after a few days Grant decided to regroup his exhausted forces in Chattanooga. Lincoln was worried about events at Knoxville, where Burnside’s army was under siege by Longstreet’s forces. The 8th Kansas was among the units Grant sent to support Burnside.

Victory at Chattanooga formally gave the Federals a railhead and supply base from which they could launch a campaign deep into Georgia. It also soon ended Braxton Bragg’s leadership of the most important Confederate army in the Western Theater. He was replaced by defensive-minded General Joseph E. Johnston when defense was becoming the best Confederate strategy.

_____

King of the Hill

After the Battle of Missionary Ridge, there was debate aplenty about whose regimental colors had been planted first on the summit. Brigadier General August Willich, 1st Brigade commander, wrote in his report, “The Thirty-second Indiana and Sixth Ohio claim the honor of being the first to plant their colors on the crest; but a few moments [elapsed] and all the colors of the brigade were in the enemy’s works.” But Colonel John Martin made sure the men of the 8th Kansas received due credit for their achievement, as he wrote in the Freedom’s Champion newspaper:

The flag of the Eighth was one of the first on the summit of the hill. The color-bearer Corporal Jno Bringe, Co. B…was exhausted near the hill, but he refused to give up his flag to another, and Corporal Harrison Jones, Co. F and Wm. Spencer, Co. I took hold of him by the arm on either side and lifted him along until he had recovered his breath. Corporal Jones—who had asked to be one of the Color-guard before the advance and behaved with great gallantry throughout was severely wounded.

The flag of the Eighth was one of the first on the summit of the hill. The color-bearer Corporal Jno Bringe, Co. B…was exhausted near the hill, but he refused to give up his flag to another, and Corporal Harrison Jones, Co. F and Wm. Spencer, Co. I took hold of him by the arm on either side and lifted him along until he had recovered his breath. Corporal Jones—who had asked to be one of the Color-guard before the advance and behaved with great gallantry throughout was severely wounded.

In a letter to his father, the colonel reiterated his claim about whose colors were the first in the earthworks:

The flag of the 8th entered the rebel works simultaneously with those of the 25th Ills and a Regt. of Hazen’s Brigade, and these were the first planted on the rebel works. We lost our Com. officer, Lieut. Foot, wounded; three enlisted men killed, and twenty-four wounded; out of 219 engaged….Of the Atchison Co., Private Adam Krutzler was killed, and Gill M. Indale and Jacob Widmer severely wounded.

According to Martin, his small regiment of Kansans also captured 500 small arms, about 100 prisoners, and four pieces of artillery. The colonel proudly told his father that the 8th had been “complimented by Genl. Thomas, Genl. Granger, Genl. Wood and Genl. Willich, on its action.” –J.W.

Jay Wertz, who writes from Phillips Ranch, Calif., thanks Ernst F. Tonsing, Ph.D., for providing transcripts of the letters of Colonel John Alexander Martin, Tonsing’s great-grandfather. Tonsing, professor emeritus of religion and Greek at California Lutheran University, is preparing a soon-to-be-published book on Martin’s life, Fearful Work: A Kansas Frontier Newspaper Editor Goes to War.

This story appeared in July 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.